Welcome to my guitar effects workshop! Today, we will study the circuit and history of the pedal, which is copied and improved by dozens, if not hundreds of companies and masters. And, of course, we will build and listen to our own copy.

Almost every audio signal processing effect in electric guitar music and analog synthesis was born from faulty equipment or setup.

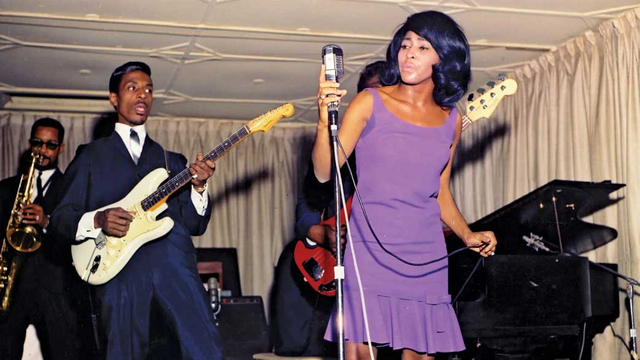

I believe the fuzz effect's history began the same day the history of rock 'n' roll began. In 1951, five years before he met his future wife and vocalist Tina, Ike Turner, founder of The Kings Of Rhythm, recorded a song named after an Oldsmobile 88.

More precisely, in honor of the innovative Rocket 88 engine installed on this luxurious, stylish muscle car.

Before recording, the Fender Bassman amplifier Ike was using was dropped, and a tube exploded.

So, instead of a pure bluesy guitar sound, the buzzing sound of the future came out of the speakers. The ensemble played rhythm and blues, but rock and roll sounded.

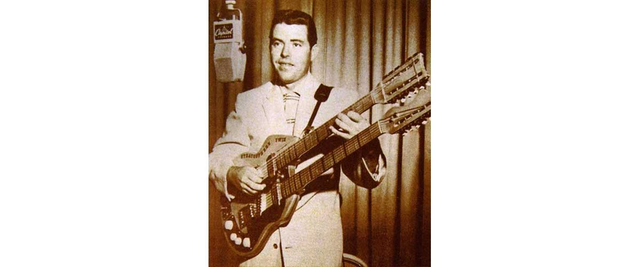

In 1961, virtuoso session musician and unusual guitar enthusiast Grady Martin recorded the bass solo for Marty Robbins's song Don't Worry through the channel of a tube mixing console that turned out to be faulty. However, not only did this not spoil the solo, which was left on the record and made it onto vinyl, but it was the beginning of a new guitar sound.

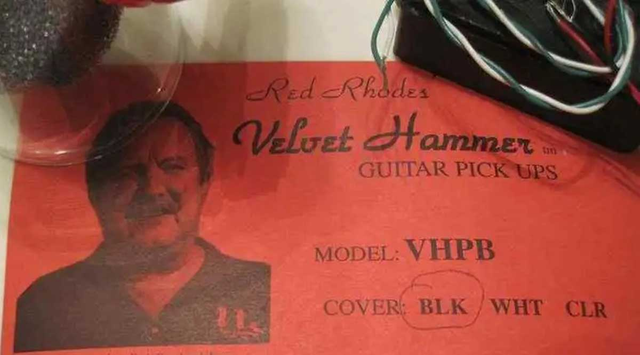

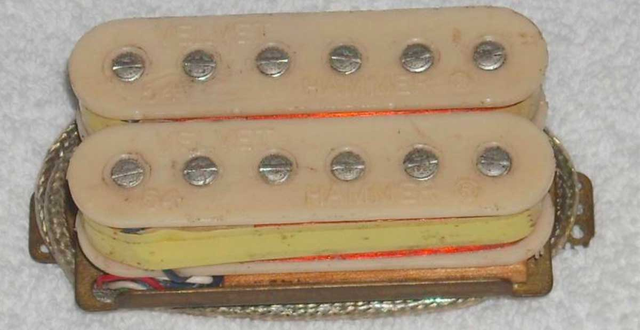

To repeat this sound, Orville "Red" Rhodes, known for his iconic Velvet Hamer pickups, created the first custom effect in a box plugged between the guitar and the amp input. Pedal-style effect boxes were invented later.

In 1962, the great Nokie Edwards, whom the Japanese call the King of Guitars, specifically used the fuzz "box" for the first time, the very one created by Red Rhodes, when recording a guitar riff. It was the single The 2000 Pound Bee by The Ventures.

Be sure to listen to this masterpiece song. The fuzz gives the composition a unique space. Each note of the guitar flashes like a firework spark.

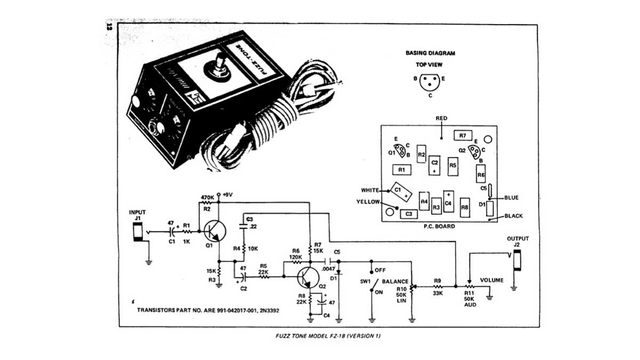

Next up. Who hasn't heard (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction by The Rolling Stones? In this song, Keith Richards used the first commercial Gibson/Norlin Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone, released already in a pedal body.

And the much more famous smiling, round-faced Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face is, of course, associated with Jimi Hendrix, the virtuoso who took the art of electric guitar playing to a whole new level.

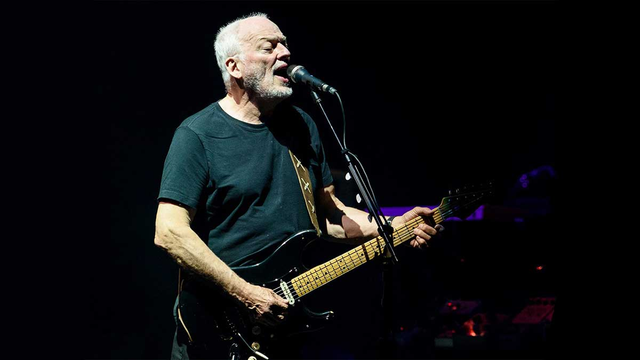

And finally, David Gilmour used the Electro Harmonix Big Muff in his masterpiece solo Comfortably Numb. This is the very pedal we are going to study and assemble today.

But first things first.

In 1967, Mike Matthews, a young IBM computer sales manager, electronic engineer, and musician and producer who had worked with Chuck Berry, among others, was impressed by the song Satisfaction, played on the radio even more often than it is now. The demand for fuzz pedals was great, and they were assembled in New York City by a single music equipment repair engineer, William Berko, in his shop, ABCO Sound, on 48th Street, in single copies.

Bill suggested that Mike work together, and every couple of weeks, they handed Alfred Dronge, the founder of Guild Guitar Company, a few hundred assembled pedals that went by the name Foxey Lady.

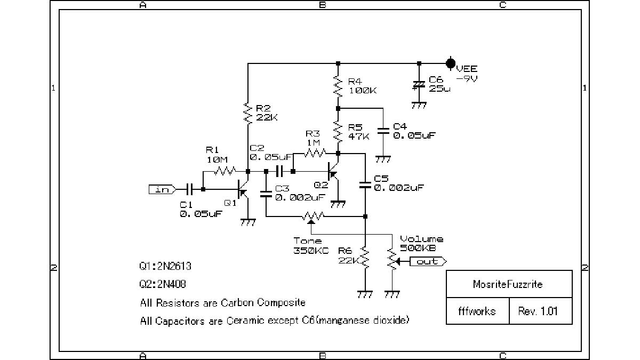

These were Mosrite Fuzzrite pedals based on the Gibson Fuzz-Tone circuit. It differs from Fuzz Face in that the second knob does not control negative feedback, i.e., gain. Still, it is a crossfader between the signals from the first and second transistors.

In other words, the knob mixes the amplified clean signal of the guitar with the distorted signal after limiting. It allows the musician to find the right balance between them. Another iconic pedal, the Klon Centaur, works similarly.

Note that the first transistor is a buffer in the original Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone. It is included in the emitter follower circuit and completely repeats the shape and voltage of the input signal. The foot switch short-circuits the output of the distorted signal.

This is simple, effective, and guaranteed to eliminate distortion of the clean signal. Still, the entire voltage gain becomes the task of a single Q2 transistor, which, for this reason, must have a high gain. In the 1960s, such transistors had to be carefully selected from many (as boutique pedal builders still do).

Instead, the Mosrite Fuzzrite uses the first transistor in a common emitter circuit, which gives voltage gain and reduces the second transistor requirements but distorts the buffered signal.

In 1968, Mike Matthews released his first guitar gear, LPB-1 Linear Power Booster, under his brand, Electro-Harmonix. The founder of the company was 26 years old at the time.

The developer of the LPB-1 was the brilliant inventor Robert Myer, who worked at Bell Telephone Laboratories. And the purpose of this silver box was not to overdrive an amplifier. Back then, guitar amps had a big headroom for clean, loud sound, and the concept of overdrive didn't exist yet, although there was fuzz.

The Linear Power Booster allowed you a long, sustained tone by amplifying the weak signal of the then-current pickups. And prolongated sustain was especially demanded from electric guitars.

An acoustic guitar cannot have a long sustain because it gives the energy of string vibrations to the air. That's how it works. But an electric guitar, especially a solid-body guitar like the Fender Stratocaster and even more so a Gibson Les Paul with a glued-in neck, gives only a signal to the amplifier through the pickups. That's why a note can sound much longer, especially if the signal is processed properly.

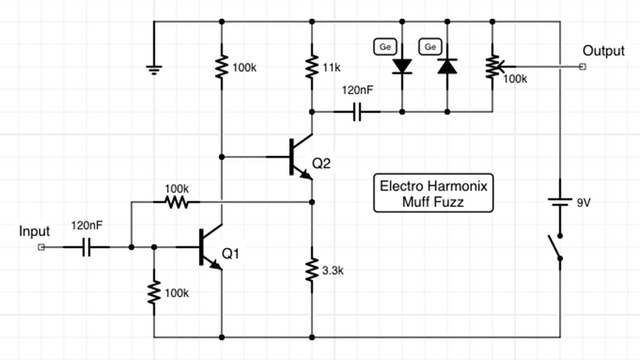

The second EHX product was the Muff Fuzz. Still not a pedal, in the same box as the LPB-1 Booster Sustainer, same one switch and one knob, only with an output socket instead of an output jack on the body.

Today, this device is available as a pedal, called EHX Muff Overdrive Nano. Then, the circuit is a Fuzz Face without a distortion control potentiometer but with added limiting diodes. So, in sound terms, it's more of an overdrive than a fuzz.

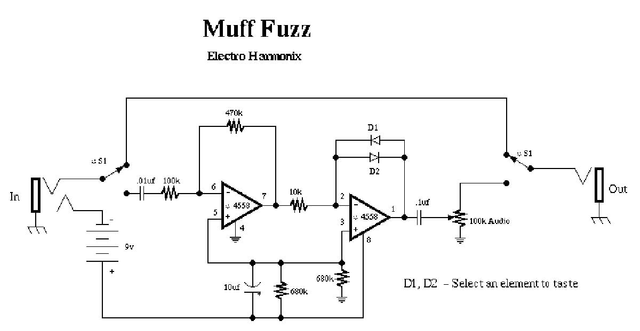

Muff Fuzz version on operational amplifiers is also produced. Here, we can immediately see that this is a pure overdrive, with only the name of the fuzz.

What if the developer combines the Sustaining and Overdrive effects, LPB-1 and Muff Fuzz, into one pedal? That is, create a pedal with three-stage gain and diode limiting on the third stage?

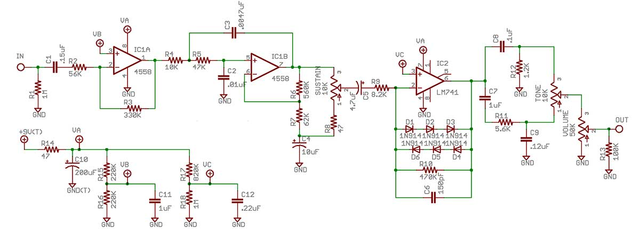

That would be the Big Muff. Like the Muff Fuzz, it exists in transistorized and op-amp versions. I will build the op-amp version from a DIY kit from Landtone.

I really like DIY kits from this company, but today, they missed the hole placement. The jack plane should be almost adjacent to the top wall of the case; otherwise, you can't install the PCB. Here, it is offset in height by more than 3 mm.

The holes are drilled the way they should be on the blue pedal, but on the silver pedal, the holes are offset.

I had to work with a drill and a file.

In the end, the board fit into the case, but it was ugly. I can't gift or sell such a pedal. (You can, of course, fill the extra part of the hole with a "cold welding" type compound, then sand it down, but it's a lot of work with no guarantee that the compound won't fall off).

Therefore, it is more reliable to buy kits where the holes are not drilled and drill them yourself. Out of 7 Landtone kits, I found offset holes only in two, and such a significant offset, which does not allow the installation of the PCB, only in one of these cases.

And now you can hear what the fantastic Big Muff fuzz distortion sounds like, with its really great sustained tone, as well as watch the pedal's assembly process.

The EHX Big Muff and its many versions, clones, and mods today continue to lead the way among the most beloved and sought-after pedals among guitarists and bassists of all styles, from metal to ambient.

Thanks for your attention! I'm going to build the kit from the last photo. On its PCB, there is space for two dual op-amps, while Big Muff has one dual op-amp and the second one single. That's why the next project promises to be no less, even more interesting.