Earlier this year, Michael Peppiatt's The Existential Englishman: Paris Among the Artists was published; the book displays namedropping and some Parisian familières, and ended up as quite the end note of what can be written about celebrities, and Paris. It is the kind of book that most people will forget about when asked of their favourite autobiographies, six months after having read it.

Enter Deirdre Bair.

I did not know of her before reading this book; I'd not even read her biography on Wikipedia.

“So you are the one who is going to reveal me for the charlatan that I am.” It was the first thing Samuel Beckett ever said to me on that bitter cold day, November 17, 1971, as we sat in the minuscule lobby of the Hôtel du Danube on the rue Jacob.

The start of the book is catchy without trying to be too engaging. It's clear that the writer is both experienced and knows rhythm; if writing a book is similar to pacing oneself for running a marathon well, this one holds up almost throughout.

Almost.

Somewhere between meeting Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir, there is a lull. It is slight, and on the whole can be forgotten. This is my only complaint about the book, and mind you, I'm reviewing an uncorrected advance copy of the book.

Au contraire, Bair writes of her own family in a commendable way, never delving into the sappy or drab. Professing the same kind of verve, she describes her own problems with deciding to become a biographer without knowing how to become one. She even asked Beckett how to, in a roundabout way:

All this went through my mind in a matter of seconds as I dropped my head into my hands and said, “Oh dear. I don’t know if I’m cut out for this biography business.” His demeanor changed immediately, as did his tone of voice. “Well, then,” he replied, “why don’t we talk about it?”

Reading about Bair's conquests with Beckett, it's easy to want to read her book about him. What makes it even more interesting is how Beckett didn't let her behind the scenes of his machinations:

Beckett was famous for never interpreting, analyzing, or explaining anything about his writings, particularly the plays. Although he would discuss modes of interpretation, MacGowran said, Beckett always fell back on the same final comment when questions got too close to the one he hated most: “What did you mean when you wrote X?” He brought such discussions to a quick end with “I would feel superior to my own work if I tried to explain it.”

It's clear to the reader—without Bair trying to blow her own trumpet—that the author has jumped through quite a few hoops to have her Beckett biography published, by Jove. It's even impressive that she contacted Richard Ellman, who'd had his own Beckett biography published before Bair did hers:

Richard Ellmann, then at Yale, told me he would never grant me an interview because if he had anything to say about Beckett, he would write it himself.

It's easy to think back to those days when readers were everywhere, publishing houses possessed greater cultural power than they do today, and how authors were discussed by multitudes of people while they were writing novels. It's also, sadly, easy to consider how Bair was subject to abject sexism, which led to rumours being spread, which, in turn, nearly led to her book not being published.

A cadre of Beckett specialists—the “Becketteers,” as I called them (all references to Mouseketeers are intentional), white men in secure academic positions of power and authority—formed my primary opposition. They were representative of a larger struggle in academia between the establishment and the perceived threat of women like me and my Danforth GFW colleagues, who were now competing for the same academic positions as the usual male candidates.

For the Becketteers in particular, I was a brazen example, the “mere girl” who had “invaded the sacrosanct turf of the Beckett world.” One or two younger members who were brave enough to speak to me privately asked if I was completely ignorant of the pecking order, while in public they shunned me so they could “keep on the good side of the powers that be.”

One of them surreptitiously motioned for me to join him as he sneaked behind a pillar in a hotel lobby at a Modern Language Association conference. “You are a pariah and I can’t be seen talking to you,” he said with a swagger, clearly feeling brave for engaging in this little clandestine conversation. His childish glee left me (unusually) speechless and unable to think up a quick riposte.

When I found my voice, I said I did not understand why I was being ostracized, since my two publications about Beckett had been received positively within the academic world. “Yes,” this man said, “in the academic world. But that’s not the Beckett world.”

Then, Simone de Beauvoir.

I love this part from Bair's initial meeting with de Beauvoir:

I began to make stuttering conversation, starting with my thanks that she would give me time on her birthday. Her quizzical look as she replied let me know I was not making a very positive first impression. “Why not?” she said. “What is a birthday anyway but just another day?” I didn’t know what to say to that, but she didn’t pause long enough to let me answer as she asked, “Shall we get to work?”

I had assumed that this was to be a brief getting-acquainted session and I had not brought anything with me; I had no notebook or tape recorder, and I had not prepared any questions. My only preparation had been to practice how to tell her, in my best French, that I had to go home on the twelfth to teach during the spring semester and would not be able to begin serious interviews until at least the summer, and then only if my schedule allowed enough time for me to prepare myself with serious reading and research during the term.

I stammered something about how I did not wish to impose upon what I was sure would be a festive evening, so I had not brought any work materials with me. She snorted in derision. There was to be no celebration, she told me; her friend Sylvie would be coming later with something for dinner, but until then we should probably get started. I fished in my bag for something to write on and could find only my date book, so I pretended it was a notebook.

I got a reprieve of sorts from asking questions because she launched right in to tell me how we were going to work: “I will talk, and I will tell you what has been important in my life—all the things you need to know. You can write them down, but you must also bring a tape recorder, and I will have one, too. We can discuss what I tell you if you need me to explain it, and that will be the book you need to write. That will be the one you publish.”

I remember clearly how I lowered my head into my hands and said out loud, “Oh dear.” I had the sinking sensation that the book was dead and done before I even got started. “What is the matter?” she demanded. “What is wrong?” I was so flustered that I could not think in French and asked her if I could reply in English. She said of course, because she read and understood the language far better than she spoke it. “That is not how I worked with Samuel Beckett,” I told her, and then I proceeded to explain how he had given me the freedom to do my research, conduct my interviews, and to write the book that I thought needed to be written.

I told her how we had agreed that he would not read it before it was published, and I even told her how he had said he would neither help nor hinder me, which his family and friends interpreted as his agreement to cooperate fully. I told her that, having worked in such extraordinary circumstances, I didn’t see how I could work any other way. I hoped that she would be generous and gracious enough to give me whatever help I asked for, but that she would also allow me the independence to construct a full and objective account of her life and work.

The following paragraphs didn't surprise me in the least, given that de Beauvoir's one of the most notable existentialists:

And so we began. I thought I would ease into my questioning by asking about her earliest childhood memories, but she went first because she wanted to thank me. “Women come from all over the world to write about me, but all they want to write about is The Second Sex.”

Here she pounded one fist into the other open hand as she said, “I wrote so much else. I wrote philosophy, politics, fiction, autobiography . . .” She seemed to be pausing to catch her breath after every genre, and then she said, “You are the only one who wants to write about everything. Everyone else only wants to write about feminism.”

It threw me off-balance, but I did not have the luxury of reflecting on her generous appraisal until after I left, when I grasped the truth in it. During the 1970s and 1980s she had been slotted into the niche of feminist icon—all well and good, but she did not want to be there in perpetuity. Aware of her many different contributions to culture and society and extremely proud of them, she wanted posterity to acknowledge all her accomplishments.

I adore this quote from Beckett to Bair after she'd mentioned the "Becketteers":

I talked so much that my wineglass was left mostly untouched, but it was getting late, so I started to gather my things.

Until then he had not said anything specific about the Becketteers’ behavior, but I think he was alluding to it when he volunteered one of the last things he ever said to me: “You must never explain. You must never complain.”

Indeed, there have been many times since then when I have been ready to lash out in retaliation for a bad review or an unkind comment, but every time I have remembered these words and I have never explained and never complained.

I also loved what Bair wrote about writing a biography and trying to stay level-headed in some way:

Joyce provided an example (one that he cribbed from Flaubert, but never mind) that I followed for everything I wrote: “The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.” (I did keep myself refined out of existence, but I was never indifferent and didn’t bite my nails; I just picked at my cuticles.)

Pascal had the perfect pensée to help me open up and confide my own experiences to the permanence of print. When he thought about how his life was “swallowed up . . . in the eternity that precedes and will follow it,” he “[took] fright.”

When I began to write biography, I was, like Pascal, “stunned to find myself here rather than elsewhere . . . Who sent me here? By whose order and under what guiding destiny was this time, this place, assigned to me?” It led me to ask myself what had ever made me think that Samuel Beckett “needed” a biography and I was the one to write it?

Saint Augustine provided the answer for what drew me to Beauvoir: I had become “a question to myself. Not even I understand everything that I am.” And Rousseau gave me hope that sustained me during each biography, but especially within this bio-memoir: “My purpose is to display a portrait in every way true to nature, and the person I portray will be myself. Simply myself.”

If I managed to do that, then I have succeeded, and I am content.

In regards to this book, I hope Bair is more than content. She should be, I think. Then again, I was born just before her Beckett biography was published. This book contains many pointers to what a writer—biographer or not—should consider.

First and foremost, this book is a tale of the ups and downs of writing about human beings, and what those human beings bring to the table while and how you write about this. This is a laudable and highly recommendable memorial of extraordinary times in the life of a very considerate and apparently skilled biographer.

This book is scheduled for publication on 2019-11-12.

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://niklasblog.com/?p=23209

It was nice to read a review like yours. It takes you in a trip back in time and makes you forget about the life we are living.

I love how you chose the words here. It means the book is real and writes about real life. I should definitely read the book, you made me want to :).

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you so much, Erikah. If you want to dip your head into another likeable book, also more than touching into the realm of humanity and existentialism, I recommend Sarah Bakewell's "Montaigne: How to Live", which gets 5/5 from me. It is truly essential.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Beckett and de Beauvoir names surely take me back to the college ages. Haha. Really interesting to read this memoir. I definitely will purchase this one.

Nice review! How did you get the advance copy of this book? Will be awesome if I can have it too. 😁😁

Cheers! 🍻

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It's lovely! I got it via Edelweiss!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi pivic,

Visit curiesteem.com or join the Curie Discord community to learn more.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hello there @pivic!

What a fantastic book review! You had got us hooked already and somehow makes me want to read sone more. It is always lovely to read about real life experiences.

Thanks for sharing a few pages with us. Good thing you got the advance copy!

Congrats on your curie love.. cheers! ❤

Posted using Partiko Android

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

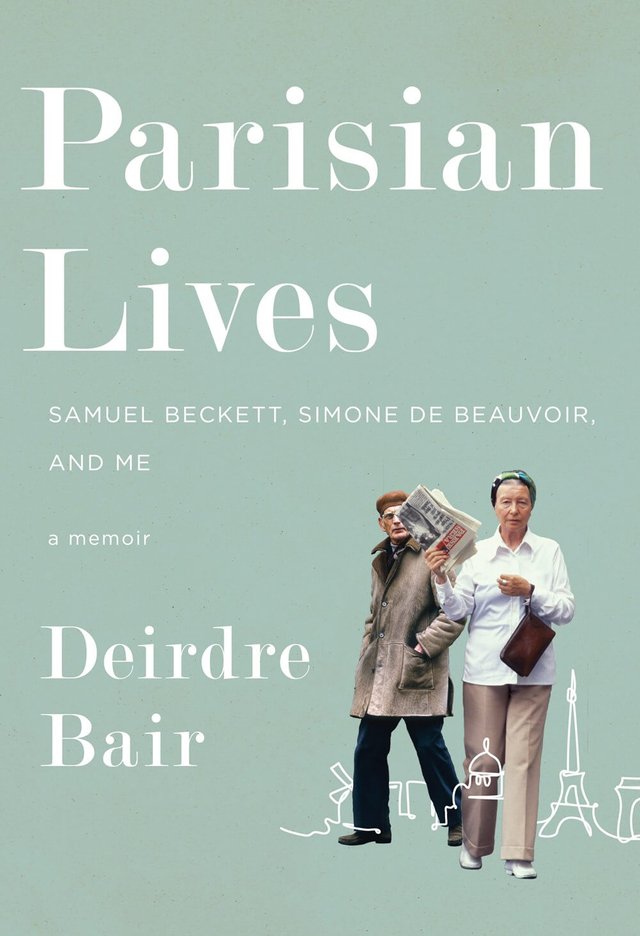

From even the look of the cover art, one could tell that this book is worth reading and it not always about the read but it also prepares you towards the will of improvement in ones writing skills. I know that right....lol

Your writing is a living testimony though. I could see great writing skills in there and you also made the story sounded more than interesting to catch my attention.

I really enjoyed every second i spent on your blog and each word in there was worth reading. Great piece and keep the writing spirit up always

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you so very much for writing that. It means something to me, and not a little. Thank you, yet again.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

You are humbly welcome

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Wonderful. What a treat: Bair's at getting to meet and write about these two giants and yours at reviewing "an uncorrected advance copy of the book".

It is always a challenge for anyone intellectually oriented to meet and deal with people of genius. Most of them are quite arrogant and inaccessible and can make the average folk feel unqualified for the task of even having a casual conversation with them at a book reading session.

But, I guess they are all human deep down and some are more willing to revel their humanity and it is a great thing when biographers are able to capture that for other generations of readers to enjoy.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It was a very good read. Like I wrote, it could just as easily have been a let-down, but Bair really keeps a cool head and knows her stuff in and out. The fact that she took years to write her biographies on both Beckett and de Beauvoir says a lot. Cheers!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Oh wow there is something called a Parisian life and people write about it, never heard of it, I used to think paris is famous just for fashion not their lifestyles.

hmmm. This is a unique post.

congrats on your curie :):)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit