The events in Damascus that took place in May 1860 are the events that epitomize the emirs lasting recognition as a man seeking worldly brotherhood. When Druze and Maronite Christian factions found themselves in a heated disagreement over equal rights for Muslim and non-Muslims, the Druze began rioting and Maronite Christians found their lives at stake.

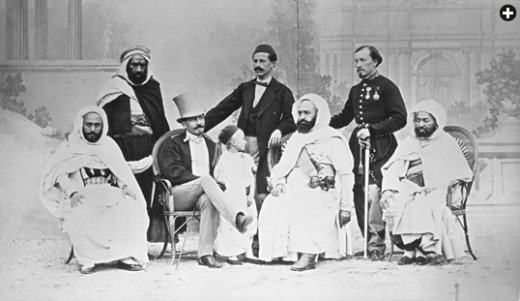

Abd el-Kader interceded on behalf of the Christians, not the Muslims, and implored the elders that their actions were "unworthy of your community". However, it became apparent that only force would win the day and Abd el-Kader gathered loyal men to his belief, armed them, even at the request of the Ottoman governor to disarm themselves, and marched into the Christian quarter to escort the beleaguered Christians into his own protected precinct. It is estimated that his actions saved the lives of over 12,000 Christians. As Charles Henry Churchill, his biographer prosaically puts it, just a few years after the event,

"All the representatives of the Christian powers then residing in Damascus, without one single exception, had owed their lives to him. Strange and unparalleled destiny! An Arab had thrown his guardian aegis over the outraged majesty of Europe. A descendant of the Prophet had sheltered and protected the Spouse of Christ."

Abd el-Kader wrote a letter after the riots in response to a thank you letter from the Bishop of Algiers Louis Pavy that is the epitome of the emir's view of mankind, especially in the face of religious differences;

"What I did for the Christians, I did because of my faith as a Muslim.... All religions brought to us by the prophets, from Adam until Muhammad, rest on two principles - praise for God and compassion for all His creatures. Outside of this, there are only unimportant differences."

His actions in saving the Christians in Damascus also caught the attention of American President Abraham Lincoln, who sent two pistols, a plaque and the Presidents thanks.

His character was now known throughout Europe, and there were even rumors that Napoleon III had an interest in seeing the emir become ruler of Syria or possibly viceroy of Algeria, none of which came to pass. However, with the years slowly catching up to him, Abd el-Kader found himself more and more viewing jihad, Islam, the Qur'an and hadith writings not in a violent manner, but from the standpoint that compassion, tolerance and service to God were the goals that all men should strive for. Near the end of his life, in a letter to a French friend he wrote,

"I have now become so tolerant that I respect all men, whatever their religion or beliefs. I dare even become the protector of dumb animals. God created men to be His servants, not the servants of other men."

Abd el-Kader spent his remaining days as a symbol of tolerance and received official and popular respect from not only the French and Algerians, but the world over. And while he fought for the Islamic law and believed in the Islamic law, he put the writings that were the rule of his being into perspective and used them as a means to bring true peace to all men. He died in Damascus on 26 May 1883 and is buried near the great sufi Ibn Arabi.

Abd el-Kader's view of jihad is not the view that is today associated with the word. Terrorism uses the word as their "god given right" to kill anyone who does not conform to their viewpoint of the Qur'an and hadith writings. The Qur'an itself is quite ambiguous when it comes to clearly defining jihad. It does however give reference to the original meaning to encompass "struggle" or "striving", neither of which dictate violence. The concept of jihad without a doubt is a continual theme for the entire history of the Islamic civilization.

Many verses of the Qur'an have clear implications of violence, while others are viewed arbitrarily and normally taken out of context to present a skewed viewpoint. During the Crusades, the term jihad was taken to mean "holy war" but this is too narrow of a translation and the aforementioned "struggle" or "striving" is more accurate. Conversely, it should be noted however, that from the beginning, with the Prophet Mohammed, jihad was issued by force and conquest was the goal. The only way for Islam to spread was through the conquest of other nations. Author David Cook relates that,

"With only a few exceptions (East Africa, Southeast Asia, and to some extent Central Asia beyond Transoxiana), Islam has become the majority faith only in territories that were conquered by force. Thus, the conquests and doctrine that motivated these conquests - jihad - were crucial to the development of Islam."

The writings of the hadith, or sayings attributed to the Prophet Mohammed, are where the viewpoints of jihad generally are taken from. Then there is the sharia, or "Divine Law" which is a composite of the jurists discussion over time to regulate the nature of warfare that were not addressed by the Qur'an or hadith writings.

The concept of jihad can be broken down into two fundamental categories. The first category is called "Greater Jihad" or non-violent jihad and the second being "Lesser Jihad" or violent jihad. Obviously the emphasis on "great" and "non-violent" as opposed to "less" and "violent" must be emphasized.

How to we then determine if the ancient Muslims believed or even conceived the idea of a greater and lesser jihad? In the early writings of the hadith the concept of greater jihad as a spiritual struggle seems to be absent. It appears that the concept of greater jihad was a Muslim apologist viewpoint and has no substantial ground in early and classical Islamic writings. Cook points out that "it then becomes difficult to isolate a single historical instance of either an individual or group using the idea of "greater jihad" in order to reject the possibility of aggressive warfare." It is clear that there are instances where jihad is of a non-aggressive nature, such as the defensive response to the Crusades.

The concept that these early Muslims were able to practice and differentiate between a spiritual and aggressive struggle seems to prevail when one looks at the idea that as long as high Muslim civilization was not in danger, the idea of spiritual struggle was present. Even to the present day, you find a document that the attackers of September 11, 2001 left that reveals their concept of mixing spiritual as well as violent jihad. Let us also bear in mind that within the Sufi tradition, to which both Abd el-Kader and Imam Shamil belonged, spiritual realization cannot but result in compassionate radiance. Realization of the absolute is, inescapably, radiation of mercy, since mercy and compassion are of the essence of the real. If compassion in the fullest sense thus flows from realization, this realization itself is the fruit of victory in the greater jihad.

Modern views of jihad and the idea of the combination of the greater and lesser jihads are certainly a product of one of the great codifiers of Muslim law, Abu Bakr al-Kasani, who wrote a clearly defined definition of jihad;

"Jihad linguistically means to devote exertion - meaning energy and ability, or an exaggerated amount of work striving - and in the legal realm it is used for the devotion of energy and ability in fighting in the path of God with one's self, wealth and tongue, anything else or an exaggerated amount of that."

The great leader of the Muslims during the Third Crusade, Saladin, is a great example of a leader who used the Qur'an and hadith to its full extent, most assuredly fought a greater and lesser jihad and was able to still maintain a balance. He was a fierce warrior, quite similar to Abd el-Kader, and just like the Emir, he knew how and when to show compassion. Like the Emir, whose outward struggle with the French was mirrored by his inward struggle with compassion and tolerance, Saladin found himself outwardly fighting an invader while inwardly struggling to be compassionate and merciful, both in the face of horrific circumstances and in situations where compassion would not be the first thought to come to mind.

When the final analysis comes in, just as with the Christian Bible, the concept of what is meant, inferred or instructed by the Qur'an, the hadith writings and viewpoints are consistently open to interpretation. However, one big difference is in the idea of violence. The Christian Bible has a significant amount of violence in it. These acts of killing that are justified are always directed by God, even if carried out by a man. Conversely, the Qur'an provides considerable amounts of killing but directed by a prophet, a man, and not God but in the name of God. Therein lays the difference and the potential for understanding the struggle to understand jihad.

Christian believers have their own jihad, their own struggle but do not condone violence. While violent acts are carried out by the misguided, they are condemned by the belief that the word of God is spread through love, not the sword. The Qur'an similarly shows that struggle with compassion and love is paramount, but the concept of violent actions in response to disbelief in Allah or his prophet is undeniable.

The concept of jihad and Islam is one of conquest. This cannot be denied as the Qur'an states it verse after verse. The ultimate goal is that everyone is converted to Islam, and therefore acceptable in the eyes of Allah. The Christian viewpoint however believes that man has no ability to change or sway another human into a relationship with God. That is God's job alone. We are merely the mouthpiece. If a person chooses not to accept, while the believer is saddened, there is no animosity, no fine, and no punishment other than what the person puts on him and what God chooses to enact on the Day of Judgment. The various viewpoints of modern day Muslims ranges the gamut from apathy to radicalism, but it should be noted that this is no different than recorded history, the Qur'an, and the hadith have portrayed jihad. Cook presents this analysis;

"one must conclude that today's jihad movements are as legitimate as any that have ever existed in classical Islam, with the exception of the fact that they disregard the necessity of established authority…other than this one major difference, contemporary jihad groups fall within the confines of classical definitions of jihad."

Abd el-Kader however, chose to take a path that many, regardless of their faith, would be willing to take. His actions proved that while he was a devout Muslim, he believed that the laws of his faith were more than conquest. For every "and kill them where you find them" [Surah 2.191] there was a "As for those who exert themselves in Us, We surely guide them unto our pathways" [Surah 29.69] for the Emir. His view of jihad was not of conquest, but of duty to God, duty to self, and above all else, duty to mankind. His views of tolerance have made their way across the globe to the small town of Elkader Iowa, where 17 year old Stephannie Fox-Dixon won the town's first essay contest and a personal connection to the town's namesake.

"Abd el-Kader had a strong sense of character, and since learning about his life, I now regard Abd el-Kader as one of the forefathers of some of the world's greatest nationalists and humanitarians, such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr."

To have that impact, that resonance across the globe over 150 years later is a testament to the life of man who as a Muslim believed in the commandments of Christ that we are to "Love your God with all your heart, mind and soul" and specifically that we are to "Love our neighbors as ourselves."

Congratulations @njb1966! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDo not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit