Twelve hours,50 pounds 2800 feet. A training run in an amazing place. Navigation above tree line on featureless terrain in the wind...and a return in the darkness.

On February 17th, I was climbing up the steep icy slope in fifteen degrees with winds of 40-50 mph five hundred feet below the summit of Algonquin mountain in the Adirondacks. That mountain has some teeth! Luckily it was just mouthing me around a bit.

Anyway, it had been about eight hours of slogging along and I had met a number of hikers moving through, some in groups between two and six on wide flat backcountry skis, others flapping along on the battered red Msr snowshoes that are the ADK routine issue. A few lone hikers passed through, generally on their own equipment. Most were heading to camping sites below the summit; these I did not meet again. But with conversations with those who were returning from the out and back I was getting the distinct sense that this was going to be the winter training alpine ascent I was hoping for- if I could ever get there! I was moving along far more slowly- partly because of the fifty pounds I had intentionally loaded up with and partly because- well, I haven't figured out the vegetarian diet yet. I have been leaning on tofu and cider a lot for protein and energy respectively- but three hours in it wasn't quite working so I followed up with peanut butter and jelly, yogurt and jelly, bananas...etc etc yackatoo blah blah... As the slope increased, my snowshoes became increasingly useless. As I understand it snowshoes are made to float on snow which puts the crampons beneath them at a distinct disadvantage when trying to dig in. With 230 pounds above them and a few inches of new snow over several feet of hard back...there was a lot of sliding and grunting going on. When I arrived at the first icy climb I put on my ice boots (the Sportiva's) and crampons with some relief.

At any rate, I got to meet a lot of people that way and toward the end of the day the accounts told of a hard possibly treacherous final ascent. Most had turned back, some had only done Algongquin rather than continue on to Iriquois as they had planned.

There was one who reminded me of John Muir, tall and rangy loping along on the Msrs with the barest miniumum of gear- he was moving fast and planned to summit and move out quickly. He had done the AT not long ago. Just below the treeline he looked down at my crampons and boots and smiled (I had ditched those blasted snowshoes) . You're dressed right there...it's pretty icy up top. I was too. Those boots have a shank that extends the full length of the boot so they don't budge at all. With automatic crampons you can actually walk up a telephone pole with them- or so the experienced say.Apparently that is the test for good ice climbing crampons.

He was the last person I saw in the treeline just before the final climb a bit after 3:30 in the afternoon. I was alone when I stepped out of the trees onto the icy slope of the final Southern approach.

It is a whole different world, those last five hundred feet : stormy, magical, elemental...just incredible raw massive power rising up beneath your feet to eye straining , neck craning heights above. On your left (East) the rock hard icy snow is carved into rifts and patterns, to the right the wind tears at you like some invisible dragon shoving, pulling, tearing, buffling in an endless conversation where you only get to gasp in response. You fumble with your compass, take a bearing...and then it is flying out to the side on it's lanyard next to your trekking pole which is also aloft. Only the mountaineering axe held it's grip. I realized that, this late in the day with my reserves depleted, it was going to take a lot of doing to use the compass alone, particularly as I didn't have a means to mark any changes in direction. I had brought flagging, but the trees I had seen last spring were buried in the snow beneath my feet their tops just projecting a few inches above the snow. Even cliffs up there are subordinates- their massive tops lurk just above the snowpack as though simply boulders.

Rope teams on glacier approaches at one time used wands with orange flags methodically placed every 180 feet for this- but I had none. So I started punching in waypoints on my gps. I admit I put in a fair bit more than was necessary :) I was taking no chances though. The trail was only a few feet wide, whiteouts are common...and working along the treeline looking for the trail can end up with the climber falling into a 'sprucehole'. Basically you fall down through the branches of a buried tree, the snow piles on top of you and you are left as much as 10-12 feet below the surface with snow piled on you. And you are generally upside down and stuck in your snowshoes...

A couple earlier in the season had been stuck for two and half days in a spruce hole on Algonquin in this way before the rangers rescued them. So I was taking no chances.

There were little or no traces of those who had summited in the prior days- they had been buried or carved away or simply vanished as mine did as mere pinpricks across hundreds of yards of icy glaze. Still I summitted readily enough. There was clumsiness, a few frenzied efforts to mask, goggle and mitten up, and pictures here, there and there, a quick video that I had to take twice because I couldn't see the screen and couldn't tell which button press was on and which was off...

None of them show the size of the billowing clouds of powdered snow, or how the minutes pass like seconds, or the strange pauses of total silence when the wind completely stops for a couple of seconds.

Of the descent into darkness I will say little; it was little different from the others or from what I had trained for. Strong tea, banannas,chocolate and the last water from a nalgene whose sides were so frozen it felt like glass were powerful restoratives. A cramponed boot that plunged to crotch depth through the snowpack off the edge of the trail was more of a pile drive than a post hole. And some trails aren't on the map but you can use them anyway.

If I have focused on the struggle more than the beauty, it is because I wish you to have a good and successful journey should you decide to take it yourself.

May you be happy.

And now the pictures...( I make this section independent should your day be too hectic...)

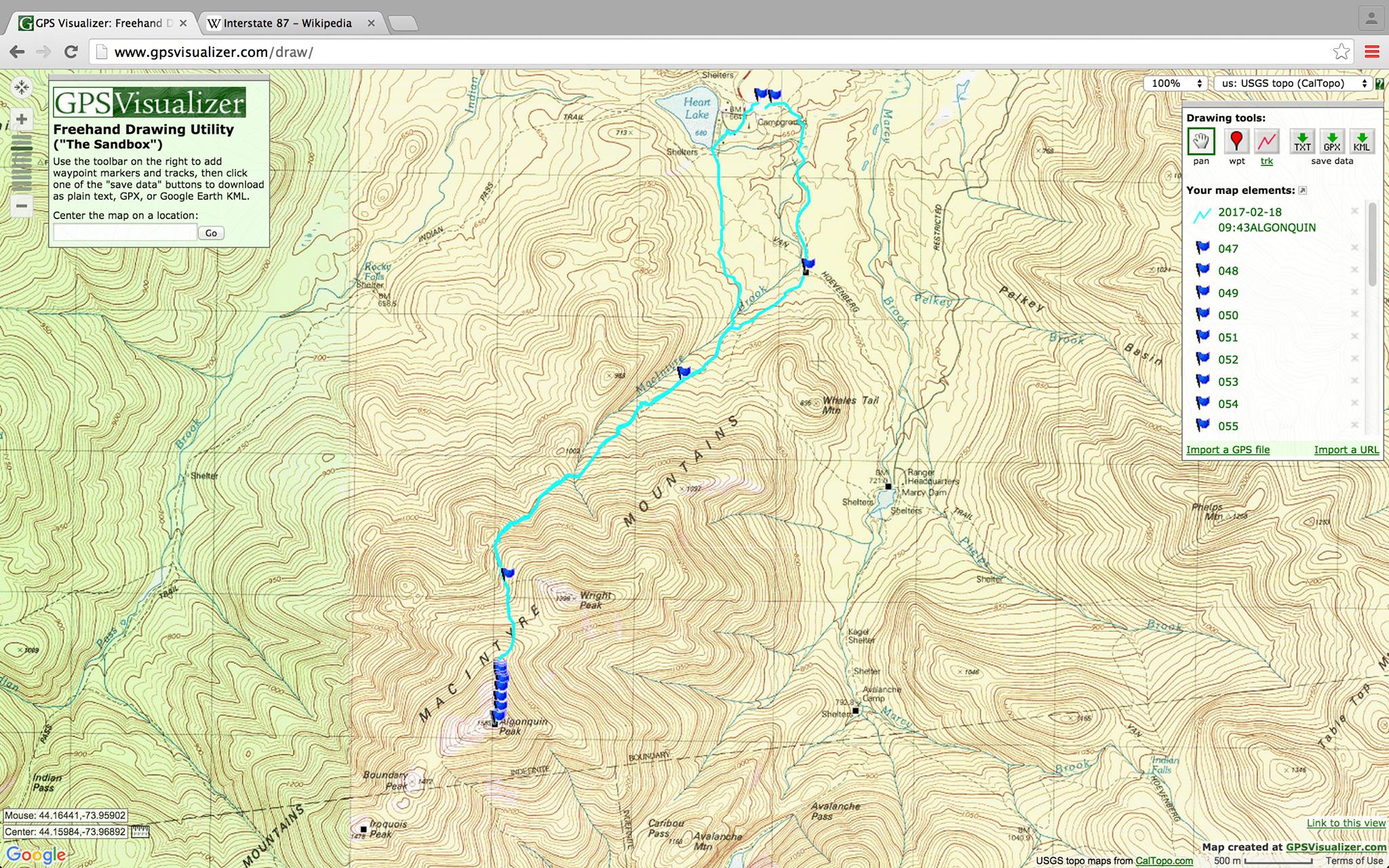

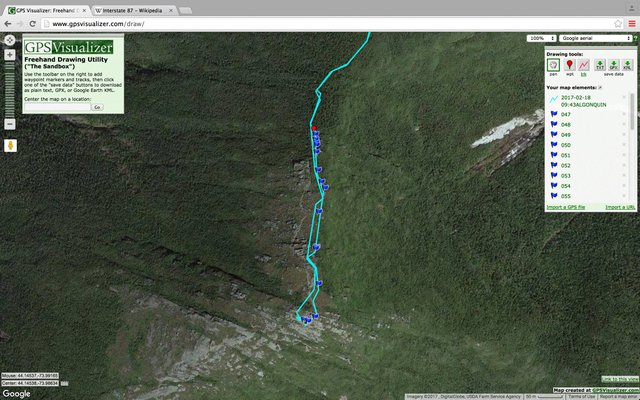

Here is route I took. It is the standard one. Note the large cluster of flagged waypoints near the peak. More on that a bit later...

The approach is tough. Basically you are grinding up the better part of 2500 feet until the final ascent above

treeline. But it's quite beautiful...

I was behind time and it was becoming apparent I might not be able to make it to the top in time to turn around before darkness. So after a certain point I thought,"I'll climb until 3:30 pm and see how I feel about it."

At 3:30 this was what I saw.

You can see most of the waypoints are taken above the treeline. From the practice in San Joaquin, El Moro I know that waypoints tend to be a bit more accurate than the track.

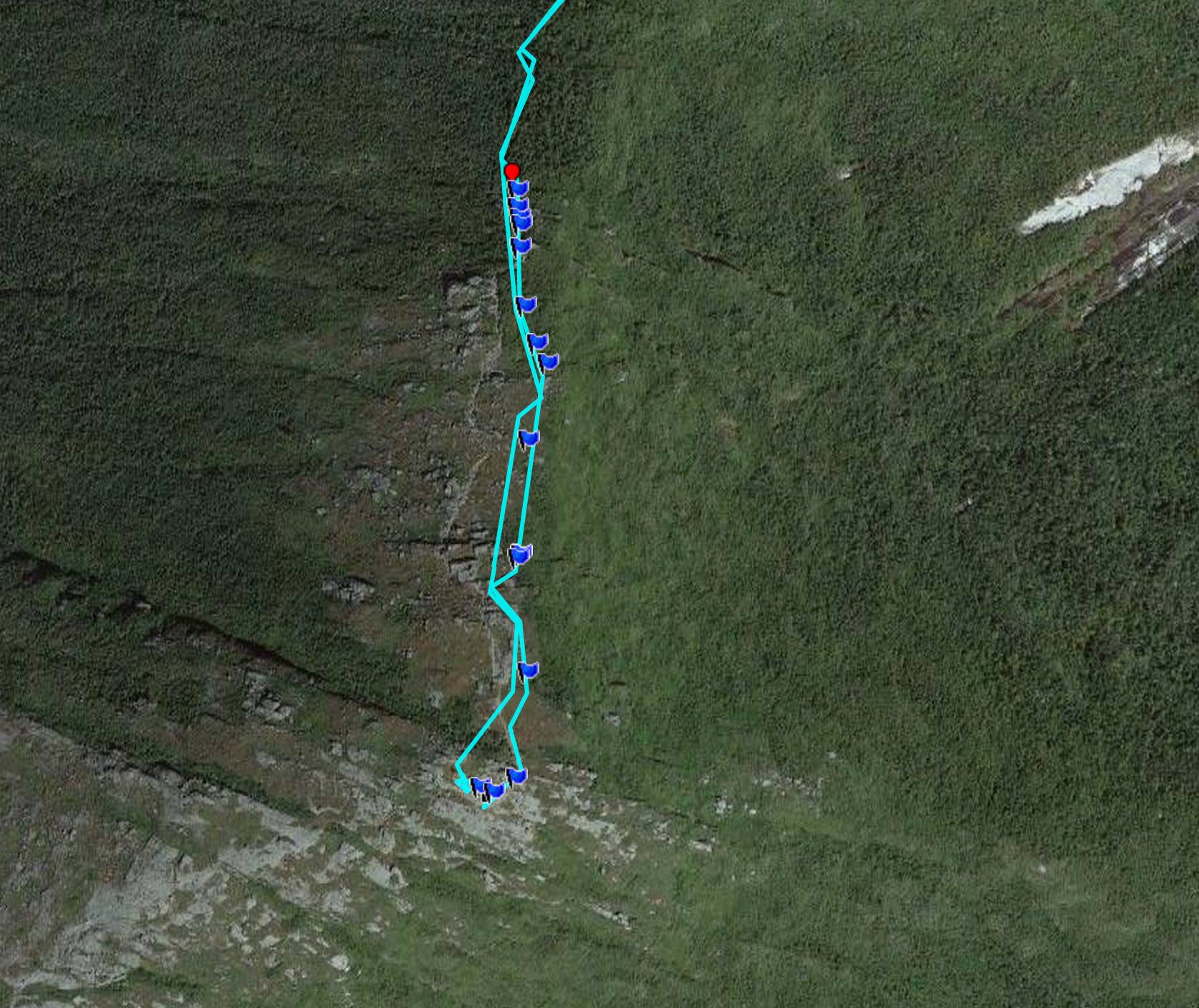

Notice the red waypoint. I just added it. It was the waypoint I wish I had taken.Right at the treeline! I realized about 50 feet on that it would be a good idea.

You can see I was taking a number of waypoints on the way up. It is probably far more than necessary but I was taking no chance that I would miss the trail.

A lot of things factor in here-

1)I realize it is late in the day, I am fatigued and have unknown additional reserves.

- the terrain is largely featureless and there is nothing to make a rock pile cairn with.

- the winds are high and seem to be picking up.

- following a compass bearing back to a 3-4 foot wide location on the top of a mountain can be very difficult- and here 'aiming off' isn't the greatest solution. If I go down the mountain on a set heading but aim for the treeline to one side of the trail it may take too much out of me to wander around looking for it in heavy winds. Also at the treeline you are actually wandering among the tops of the spruce trees. Sometimes hikers will break through the snow and branches and fall as much as ten to twelve feet. It can be very difficult to climb out of a 'spruce hole'.

The current method particularly under poor visibility is to take compass bearings but use gps waypoints near any small outcropping ( actually a several meter high cliff buried in packed snow). as you go.

On featureless terrain like glacier climbs climbers would actually use wands with orange flags to mark their return path. On one end of a line of climbers one person would hold the compass. On the other a person would place the flag.

This is to the east as I make the final climb. Notice the wind carved snow... I actually am turned toward it away from the prevailing wind because I haven't put my face mask and goggles on yet (a mistake- it seems with these mountains it's best to always put on all your layers before you leave the treeline)

It looks like a path...but it vanished soon after buried in windblown snow. Those are the tops of trees...

At last, the summit! People often speak of conquering mountains. I don't. I think of myself as a guest who must come in respect and, if I am lucky, get to leave that way.

I'm guessing this is in 40-50 mph winds- not enough to knock you over but if you drop a mitten on the ground you'll want to grab it in a hurry. It moves like a piece of paper across a parking lot! It pushes you around just a bit and makes getting things out of your pack problematic.

I wore goggles and a face mask up here and they helped considerably.

On the descent. Darkness would be coming soon and I am eager to get down to 1100 meters below the first big ice ledges.

These pictures are looking at Wright mountain, a bit closer in on the MacIntyre range.

Looking back at Algonquin from the treeline. I took few pictures above the treeline on the way down because I was more focused on getting back down the steep icy slopes.

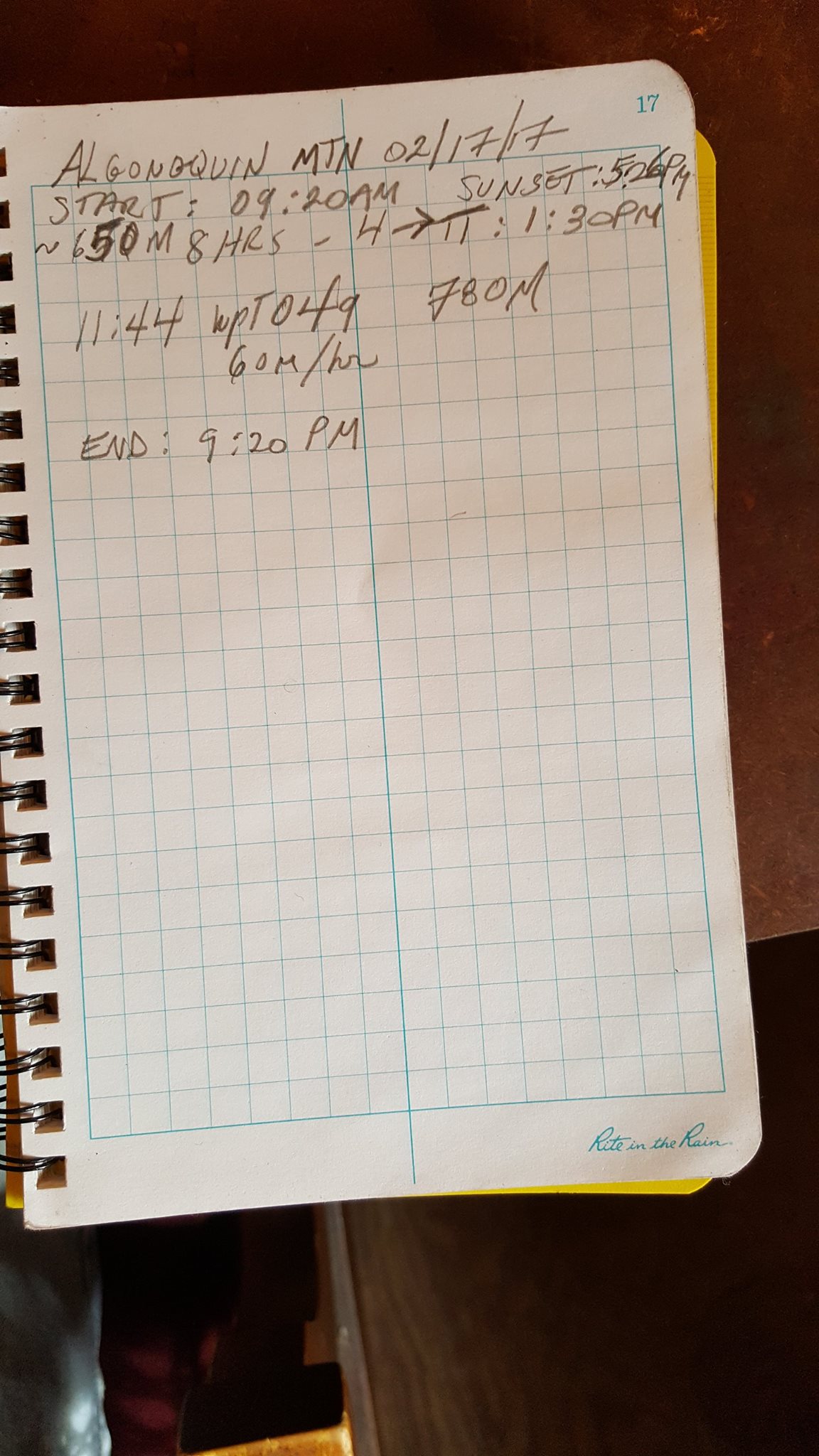

And here is my notebook for said action packed day. Notice the lack of entries. This was a tough day for writing in the book apparently. Near the summit where careful notes could have helped it wasn't feasible in the heavy winds; recording has to be done in some other way. Perhaps a small notebook strapped to the wrist...

I of course ignored the turn around time except to periodically remind myself how far I was going beyond it. Ultimately, I would descend from the summit around 5:20 pm. So it took me 8 hours to get there and 4 hours to descend. I took one 15 minute break on the way down and of course time at the summit but the rest of the time was more or less a continuous slow climb with 1-2 minute rests.

Snowshoes are a lot harder to use when there is a steep slope and a new layer of snow. The crampon spikes on the shoes don't give very good traction at least in part because your weight is being distributed over a larger area. Once it got very steep and I switched to crampons things got better traction wise.

Getting more information about time by rummaging around the inside of the gpx file for the waypoint data. I can see that I marked the summit point at 5:18 pm and that I entered the alpine zone around 4:46. Basically it took a half an hour or so for the final climb and I mucked about at the summit for about 6-10 minutes.

Excellent story. You are brave to head up there in the middle of February.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks mustang! :) The key lies in the 50 pounds of gear on my back. There are two schools of thought

'fast and light' (i.e. get up get down get out fast before you get hit by a storm or something happens) and the 'slow and heavy' (i.e. carry enough gear to wait out bad conditions until you can get out or rescuers come).

I am of the latter group so I have a tent without poles, a sleeping bag and extra clothes in case something happens.

But yes, every summit has a little bit of fear and respect in it. You know you are a guest...

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

amazing photos! haven't had time to read the whole story, but I'll get to it later. Inspirational stuff. Got any other treks to share?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

finished the story. fantastic. i love the way you include photos of your travel log. so many nice touches.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thanks crumb-bum! :) I will be sure to include the travel log in my future posts.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I am glad to have joined the same group as you.

And it is a extra bonus to see that you have interesting posts also.

And here is my first upvote.

I hope you have a great day when you read this :)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit