Rather than an academic AI conference, it was more of a cross-disciplinary gathering of people who believed that accelerating technological growth would cause radical societal change in our lifetimes. There was a mix of AI people, biotech people, nanotech people, and people from various other fields.

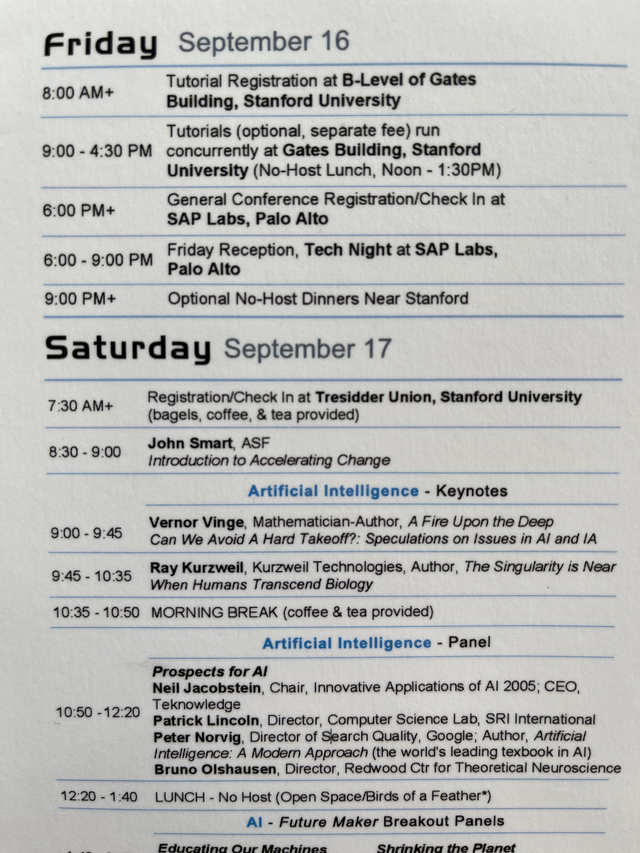

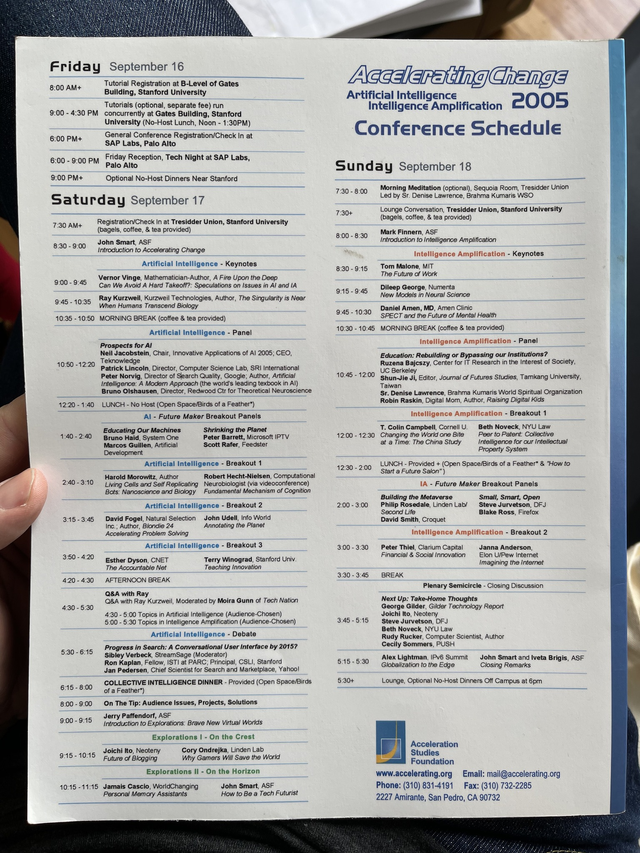

Speakers included Ray Kurzweil, Peter Thiel, Steve Jurvetson, Peter Norvig, and the sadly-recently-deceased Vernor Vinge.

It's hard to overstate what a fringe concept AGI was back in 2005. If the CEO of a major public tech company talked about AGI as a serious business consideration in 2005, they would have been branded as a lunatic and likely unfit to lead. Now it's everyday conversation for the leaders at places like Microsoft and Google.

Looking back at the agenda:

AI has arguable met or exceeded the high expectations of the speakers and attendees! One talk posited a "natural language UI" by 2015, and Ray Kurzweil was predicting human-level AI by 2040. The "natural language UI" people were only a few years off, and probably the products that Google and Apple released in the late 2010s would have qualified. Current AI chatbots would definitely qualify, and people from 2005 might have been willing to slap something close to an AGI label on them.

Biotech and consequent life extension technologies have been very slow in coming relative to expectations in 2005. At that time there was a lot more optimism that the recently sequenced human genome would yield some reasonably clean genotype->phenotype mapping, and that would enable us to start pulling levers to increase lifespan. I'm excited that we can polygenically screen embryos now and that technologies like CAR-T immunotherapy are significantly increasing many cancer survival rates, but so far human lifespan has not been particularly improved. I'm guessing that the next 5 years will hold more development in this area than the last 19.

Robotics has improved at a slower rate than expected. There has been a good amount of progress, but note that the Boston Dynamics Big Dog was already walking around the hills of Massachusetts in 2005, so people were expecting humanoid robots that could do most human tasks by now. Hardware is hard. The progress in computer vision and RL has been fantastic, and it seems like that is starting to impact robotics, but there are likely still a lot of obstacles ahead. The biggest gains seem to have come from doing simple things at very high reliability -- eg Amazon's mostly automated warehouses.

Nanotech is maybe the biggest disappointment. I'm not saying there hasn't been progress, but we don't seem much closer to the "molecular machines" posited by Drexler now than we were in 2005. Much of the progress seems to be happening via biomachinery -- things like custom designed vaccines in viral delivery systems. It's impressive work, but we're taking the amazing tools that nature evolved and making tweaks to them instead of building a new architecture from scratch.

"The metaverse" was an interesting one. Second Life and World of Warcraft had both recently come out, and this felt like a primitive instantiation of Snow Crash minus the VR goggles. We amazingly now have the VR systems that everyone dreamed about in 2005, but it turns out that the metaverse as a concept has been kind of slow in coming. VR is not as popular as I would have expected it to be given the quality of the headsets now, and when people are in VR they mostly play Beat Saber and shoot-em-ups instead of inhabiting a metaverse. The most popular metaverse-y thing people do nowadays is probably Fortnite.

What everyone missed: (1) Low cost access to space. No one expected reusable rockets and constellations of thousands of small satellites. (2) The impact of the mobile / app revolution. Even though smartphones existed via Blackberry and others and social media was already big, no one was really paying attention to how smartphones + social media would impact the world. Lots of people predicted pervasive AR/VR, but no one predicted a society of people staring at their phones all the time. (3) Self-driving cars. The first DARPA grand challenge win happened just a few months after this conference. It took a long time to finally see them deployed on the streets, but they are here and they work very well.