Lessons from Blue Apron, Uber, Amazon, and Facebook

Remember the beach? It was always a battle to build the best sandcastle. But inevitably the tides turned and waves washed away your creation… you were devastated.

I hope you learned your lesson.

Moats are the most important aspect of any business. A defensible moat is the difference between lasting value and profitability and being ripped apart by the waves (ie competitors).

And while every entrepreneur “knows” they are building an unbreakable moat, is that really the case?

Moats

Rats run towards food, founders flock to money. Large opportunities lead to fierce competition — and nothing ruins venture returns quite like competition.

There is a saying among investors.

“Being ‘right’ doesn’t lead to superior performance if the consensus forecast is also right.” — Bill Gurley

Consensus never pays.

Competition catches on to obvious ideas (hence the issues with Uber’s business model).

Uber built a business around the “idea” of a moat. Because of local network effects between riders and drivers, Uber was able to build incredibly strong local networks — and raise over $22B to fund their expansion.

I won’t dig into the issues with Uber’s model/assumptions again, but instead want to use their “moat” as an entry into the various moats most businesses employ.

So, how do you keep competitors at bay?

Many many moats

In business there are many ways to stand out. And what is defensibility if not a reason to choose one brand over another or to remain a customer.

A moat either traps customers on your island or makes your castle an attractive destination… both acquisition and retention drive revenue.

It boils down to:What is your unique competitive advantage?

Without that you don’t have a business. With that, you may have an empire…

Broadly speaking there are 7 customer acquisition and 3 customer retention moats that power the vast majority of businesses.

The best businesses build barriers for both.

Acquisition moats:

- Brand

- Network effects

- Product

- Patents and/or proprietary products

- Licenses

- Distribution

- Pricing power

Retention moats:

- Brand

- Network effects

- Switching costs

Understanding moats

Acquiring customers is sexy. People prefer increasing revenue to cutting costs — it is our shortsighted, ego driven nature. In venture especially, revenue is king. If we can acquire customers and make money, we will figure out the economics eventually. Raise round after round until you figure out profitability, right?

Of our acquisition advantages, I’d argue all but network effects are pretty well understood.

You know why you buy Apple (brand), use Comcast (no choice), prefer Netflix (great product) or get the best deals on Amazon (price + selection)… acquisition is relatively easy to understand.

The biggest misconception is with network effects, specifically anticipating them.

The same is true for retention. It is a nightmare to change your bank and you’ve always voted Democrat (brand) so why switch things up? If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

The nuances of network effects

Nothing trumps network effects. Businesses without strong network effects (NFx) always struggle, both in terms of growth and profitability.

Thanks to business basics and GAFA’s chokehold on the economy (and our attention), we all have at least a basic understanding of network effects. (For more on the 5 types of network effects and how to hack them, see this post.)

The problem is, by assuming we understand and can anticipate network effects, many entrepreneurs set themselves up for failure.

6 misconceptions about network efforts:

1. Word of mouth ≠ network effects

Telling friends about Facebook improves your experience, the same isn’t true for Starbucks. At best Starbucks gets more business, at worst I’m stuck behind more coffee crazed addicts waiting for a fix…

Word of mouth is a powerful tool, but by itself does not constitute a network effect.

2. Incentivized referrals ≠ network effects

The same holds here. Incentivization is a great acquisition strategy but not a defensible, product enhancing network effect in the majority of instances (cryptocurrencies excluded).

3. Data ≠ network effects

Data alone doesn’t define a network effect. While data is incredibly valuable to understanding and influencing customer behavior, it only becomes a product improving network effect once you learn to effectively utilize it. Plenty of companies capture mountains of data — they just don’t know what to do with it. Insights are valuable, noise isn’t.

4. Law of diminishing returns still applies

Network effects never die, but the resulting impact on overall defensibly and product has diminishing returns. The 2 billionth person on Facebook did little to improve either social graph connectivity or user behavior patterning…

Network effects, like everything else, operate in an S curve, the question is how high is the ceiling?

5. Not all network effects are international

Case in point, Uber. Uber’s product improves as local usage increases, but NYC having more drivers and riders, does approximately nothing for my experience in Zurich. That means local networks are secure but also frail as competitors can enter any individual market, outspend incumbents and claw their way to the top.

In the situation of Uber, because ANY city or country can create competitors and any fool (or fund) can fund those upstarts, the competition tends towards infinity. What happens when supply exceeds demand…

6. Scale decreases CAC, ie improves economics

See below.

Blue Apron’s big problem

We mentioned Uber, but Blue Apron is a more interesting example.

Founded in 2012, Blue Apron pioneered the subscription meal kit. Get all the ingredients for an at-home, five star meal — no worry, no hassle.

The value prop was obvious: easy, convenient, healthy, home cooked, tasty meals. What family wouldn’t want that? And even though the price was a bit high, Blue Apron targeted the upper middle class anyway — it is a health food thing…

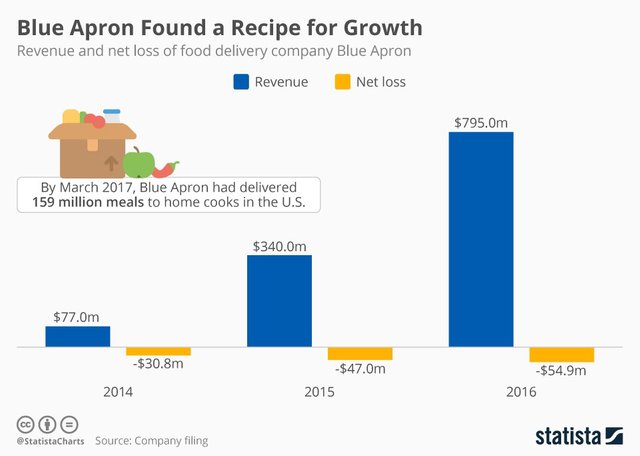

Growth was spectacular, it just took off.

And investors ate it up, literally. To date the company has raised just south of $200M (excluding IPO).

On June 1st, 2017 Blue Apron filed for IPO. They were looking to raise $500M from public investors to further growth of the company and hit scale. Interestingly their unit economics were still a bit shaky. But that was okay, plenty of companies had gone public prior to hitting profitability. As long as you were moving towards profitable, everything was on track.

Unfortunately Blue Apron’s acquisition costs and business model were built around a relatively long payback period and anticipated a decreased CAC (cost of customer acquisition) because of course network effects would spread the service (via word of mouth etc…)

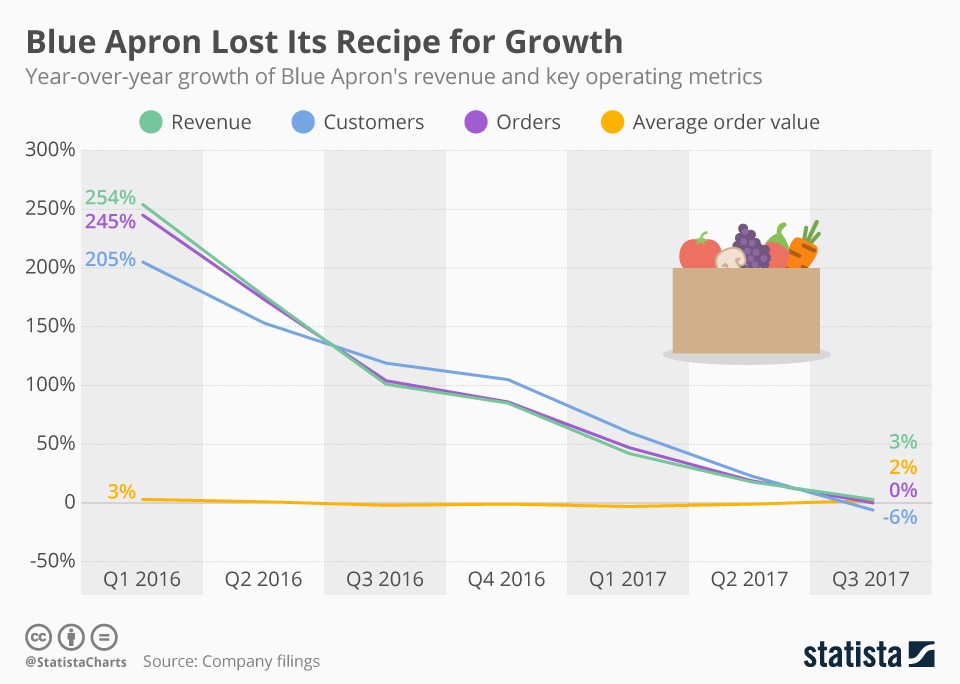

It didn’t quite turn out how they planned. Instead customers cancelled at higher rates and it became clear that between market saturation (of high end healthy foodies) and increased competition from other startups, Amazon and even supermarkets, made acquiring and retaining customers much harder and more expensive.

KN_.jpg]

Blue Apron priced their IPO at $15–17 per share. The numbers speak for themselves.

Evaluating network effects

In hindsight, it is obvious to see the flaws with Blue Apron’s business model. The network effects are little to non-existent and competition kills margins. There is no advantage to me as a consumer when my friends use the service. My food isn’t better, it isn’t cheaper, it isn’t faster… Why tell anyone about it?

“Hi, guess what… I’m cooking for my family, but kind of too lazy to do it myself…”

Someone screwed up here. And while investors made out like bandits (if they sold in time), retail investors were left holding the bag.

The question is and will always be, how do you evaluate network effects?

Both as an investor and as an entrepreneur, it is critical to understand the business model and how unit economics and CAC/LTV ratios can change over time.

In Blue Apron’s case they were aggressive with projections. By assuming growth equated with a decreasing CAC and that LTV/retention would remain constant, they set themselves up for failure. The economics could never work.

But the opposite can be equally as detrimental. This occurs most frequently with bootstrapped startups. When startups grow purely via organic growth (or fail to foresee improving unit economics), they can underspend and forfeit a lead. Plenty of funded companies are willing to burn through cash to close the gap and capture the market — slow down for a second and you can be overtaken…

Which mistake is worse? It really depends on the market and the competition. But in the world of venture scale returns, both can come back to bite investors — hence the go big or go home mentality.

Numbers never lie

Blue Apron’s finances were not the problem, the assumptions were.And while eventually the assumptions are proven incorrect, this isn’t always the case in the short term.

In the middle of the hype cycle (ie S curve), it looks like you are going to the moon. The business is taking off, CAC may even be decreasing due to increased exposure in the market and all-in-all the business looks pretty damn good.

But what happens when the ceiling hits sooner than you anticipated or other factors like competition or retention rates begin to change? Suddenly your proven assumptions are shaky, the market reacts and your stock craters…

Productive pessimism

I was interviewing an investor (can’t remember who) for The Syndicate podcast and he said something pretty profound.

“In a room full of optimists, it pays to have at least one pessimist.”

This is important, especially as the stakes become higher. Startups are stupidly optimistic. That is why they take on the world and the impossible and they win. But there comes a time in any company’s lifecycle when a bit of pessimism (plus realism) starts to become beneficial.

If you are willing to listen to the negative nancy, you might be able to avoid the Blue Apron balloon. Questioning the assumptions and beliefs in their apparent network effects would have saved the company a lot of headache.

Unfortunately this is a delicate balance.Negativity neuters greatness.Pessimistic, realistic view points early on can stifle innovation (hence why no one likes lawyers). Move fast and break things is a great motto for a startup.

But you need to know when to put on the big boy pants.

Understanding incentives

Founders and VCs both focus on enormous returns. Carry creates a scenario where investors focus on outsized returns over all else (for more on carry and economics of venture investing, see this article).

This can make ventures capitalists a horrible partner/pessimist. It is in the VC’s best interest to push the envelope and their excitement over large returns can cloud judgement.

It is easier to tell someone they have an ugly baby on the bus than at a family reunion. You aren’t tied together for life or even directly associated with the outcome — in other words, you can be brutally honest without subconsciously seeing green (happy to chat if you need advice).

First principles

Questioning assumptions is the best way to pressure test your projections. Keep asking why and eventually you get to the root of the question.

The best founders and investors are able to “see” the future. I’ll leave you with a little Elon.

Closing thoughts

Nothing beats flywheel network effects — but nothing is harder to conceptualize, create and scale either…

What moats are you most excited about? How have you backed defensibility into your business?

Investors look hard at barriers to entry. Well defended castles create kingdoms. Those are the kind of companiesour syndicate invests in. And those are the kinds of strategies and tactics I advise startups on.

It doesn’t take genius, it takes first principles thinking and a hell of a lot of effort, analysis and testing.

Build your business, run like hell but be sure you are building a moat in the process. Snapchat sort of missed the ball here, as did Blue Apron. Both were great outcomes, but both were build on a mountain of sand.

Sandcastles have a tendency to wash away.

Before you go…

If you enjoyed this article and learned a lot, please click through to the original Medium post and Clap it up to help reach and educate a larger audience.

Hold down the clap button 20–50 timesif you liked the content! It helps me gain exposure.

And while you are on Twitter, give me a follow@itsmattward

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://thesyndicate.vc/think-understand-network-effects-dont/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit