Preview of my article on Changing Times about the Asia for Animals conference in Kathmandu

Delegates to the 10th Asia for Animals (AfA) conference grappled with the issue of changing human behaviour, which was the theme of the gathering.

There were inspiring presentations about successes in animal conservation, but attendees also heard heartbreaking stories from throughout Asia about cruelty, loss of habitat, the illegal pet trade, and the trade in animal parts.

The conference, which took place in the Nepali capital, Kathmandu, from December 2 to 5 last year, brought together more than five hundred people. They ranged from those working on the ground in rescue and rehabilitation organisations to animal advocates, veterinarians, scientists, scholars, and those working in education.

The delegates hailed from 190 organisations in 45 countries. There were more than 170 presentations on issues ranging from reducing the ivory trade in China and tackling donkey welfare to saving mountain frogs and ending animal testing in cosmetics.

During the conference, participants heard the good news that Instagram users will now see a warning message that pops up if they search for, or click on, a hashtag that “may be associated with posts that encourage harmful behaviour to animals or the environment”.

Instagram had already prohibited the posting of content that overtly depicts animal abuse and offers endangered animals or animal parts for sale.

Now, when users see the new notification, they can click through to a help centre page on which Instagram encourages people to be mindful of their interactions with wild animals, “and consider whether an animal has been smuggled, poached, or abused for the sake of tourism”.

Instagram tells people to be wary when paying for photo opportunities with exotic animals, “as these photos and videos may put endangered animals at risk”.

It says it is working with wildlife groups to identify photos or videos that violate its community guidelines by depicting animal abuse, or condoning poaching, or offering endangered animals and their parts for sale.

Ismail Agung from International Animal Rescue, who gave a presentation about the illegal wildlife trade in Indonesia, told conference attendees that syndicates were increasingly using Instagram to display animals for sale.

Agung spoke specifically about the trade in slow lorises and said social media was a double-edged sword. It could encourage conservation efforts, he said, but could also be used to advertise slow lorises for sale.

A captive slow loris in a market in Jakarta, Indonesia, has its teeth ripped out. Photo by the CEO of International Animal Rescue, Alan Knight.

The trade in donkey skins

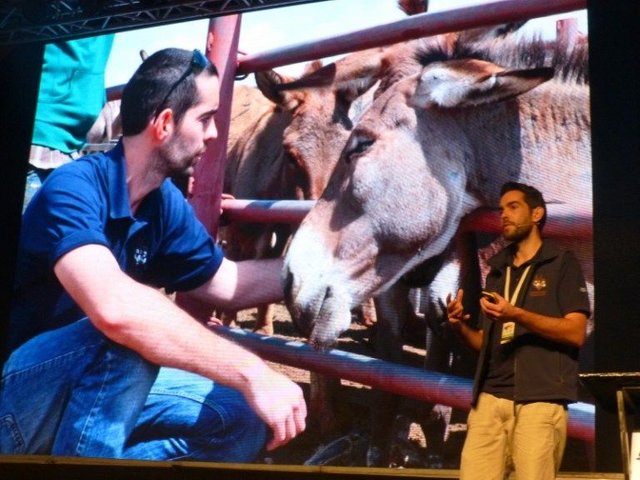

One of the most disturbing presentations at the AfA conference was the one given by Alex Mayers from the UK-based Donkey Sanctuary, which runs programmes in forty countries.

Photo © The Donkey Sanctuary.

Mayers talked about the horrors of the donkey skin trade. The sanctuary staff first heard about the trade in Africa.

“We heard stories about communities in Kenya losing their donkeys. They were being found near the house, slaughtered. The skins had been removed, and the carcasses were just left lying there.”

The sanctuary produced a report in January this year entitled “Under the Skin“, which details the devastating scale of the trade.

“The skins are taken from donkeys and boiled down into a gelatine, which is then turned into a medicinal product called ejiao. This is sold, mostly in China, and it’s used as a blood tonic.”

As the population of donkeys in China has fallen dramatically, middlemen have been seeking a supply to meet the demand for ejiao, Mayers says.

“The current supply for the trade in ejiao is about two million donkeys per year,” Mayers said. “The current demand for donkeys is more like ten million.”

Donkeys are being killed for their skins in numerous countries around the world, Mayers says. These include South Africa, Egypt, Botswana, Peru, Pakistan, and India.

“Donkeys are being stolen from communities that rely on them for everything – for water, and access to food markets. People are waking up to find their animals slaughtered in the bushes nearby.”

There is also a legal trade in slaughtered donkeys, Mayers says. He told delegates about a slaughterhouse in Kenya that has been closed down.

“That’s partly because of an investigation that we were doing, looking at the environmental consequences of this particular place. They have a ‘breeding ground’, which is in fact a dump site where all the donkey carcasses are just left to rot.

“It’s causing a huge environmental catastrophe in that community.”

Sick, injured, and heavily pregnant donkeys are transported and killed for the skin trade, Mayers says. “We are seeing many cases of spontaneous abortions on the road.”

Tiger skins have been stuffed in amongst donkey skins for export, Mayers adds. “It’s the same with drugs, and with pangolin scales.”

Five countries – Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Ethiopia – have banned exports of donkey skin.

Positive interactions

In a welcome contrast to the horrors of donkey slaughter, Mayers (pictured above) talked about the positive influence of donkeys in their interactions with humans.

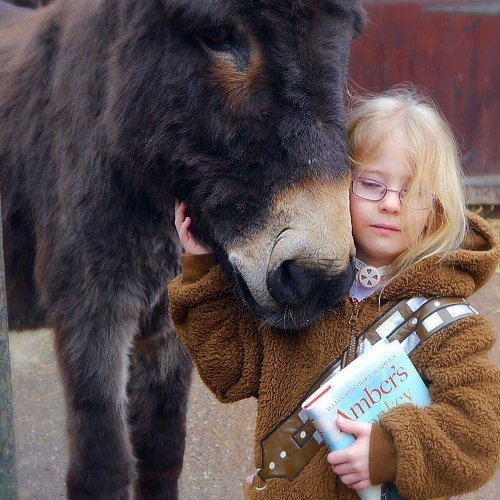

Mayers showed conference participants a photo of a girl with cerebral palsy with her donkey, Shocks, and told them that donkeys “will match their heartbeat to the person they are with”.

Riding Shocks helped develop Amber’s muscles and there was a gradual change in the timid donkey, who blossomed and became friendly and confident.

Amber and Shocks. Photo courtesy of The Donkey Sanctuary.

The suffering of bears and elephants

Gilbert Sape from World Animal Protection (WAP), who gave a talk entitled “Wildlife not medicine”, talked about the “unnecessary suffering” of bears farmed for bile.

During one of WAP’s microchipping drives in Vietnam, Sape vividly remembers seeing one bear being kept as a pet.

“This bear, who should have been enjoying the sun and the rain in the wild, was stuck in a 2.5- metre by 1.5-metre cage in a damp and dimly lit garage.”

The bear, Sape says, has been stuck in the same cage for 12 years and will probably remain there “until a fundamental change in government policy, and the owner’s behaviour, happen”.

WAP pioneered microchipping of captive, farmed bears in 2005 in Vietnam to prevent the entry of new bears into the bile industry.

As a result of microchipping, the number of captive bears in Vietnam was reduced from 4,000 in 2005 to the current figure of 900.

Sape says that the consumption of traditional medicines that contain animal parts is at risk of increasing as the purchasing power of people in China and elsewhere goes up.

Bear bile comes from farmed and mostly sick bears, Sape says. “In China alone, there are approximately 20,000 bears in farms that supply the industry.”

Education is key in changing behaviour, Sape says. The first task in changing human behaviour, he says, is to unbox the issue and unwrap and expose the cruelty involved in bear bile farming and such practices as the use of elephants for tourism.

“Wild animals belong in the wild, not in farms or entertainment venues.

“We need to educate people that bears have permanent holes in their stomach so that bile can easily be extracted on a daily basis; that elephants need to be broken and their spirits crushed to make them docile and passive so tourists can ride on their back.”

Sape has noticed the quietness of elephants used for rides. “Not a sound came from them; their eyes were dazed. You can sense fear and sadness.”

He compares this with the behaviour of elephants he has seen who were without chains and could roam freely, and were not used for rides and shows. “They were noisy – in a happy way – and full of life.”

Consumers in China believe that tiger parts can cure malaria, skin problems, meningitis, insomnia, fever, toothache, laziness, pimples, haemorrhoids, and even alcoholism, Sape says.

“The list is endless. We need to demystify the myth that wild animals are a panacea; that bears and tigers are medicines. They are wildlife, not medicines.”

Behavioural change doesn’t happen overnight, Sape says. “It took 14 years to end the bear bile industry in South Korea, and it took more than a decade to get the commitment of the government to provide a sustainable solution for the captive bears intended for the bile industry.”

A bear used in the bile industry in South Korea. Photo courtesy of Green Korea United.

This is an extract from Part 1 of my conference round-up. The full article is available at https://tinyurl.com/ybso97vp. Part 2 of my conference round-up is available at https://tinyurl.com/y7kh5aw .

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://changingtimes.media/2017/12/11/asia-for-animals-combatting-cruelty-ignorance-and-greed/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit