So we’ve officially kicked into our series on the EMPOWER project and hope that you are equip with the glossary and context of the project. If you’ve just discovered us, check out our first two posts! We’re extremely motivated and excited to be discussing more in the comments section with you. Thank you for all the positive feedback and interest in the project! If you think you’ve got some skills contributions that would fit into the project, let us know! Like we said, the collaboration network is constantly growing.

Today’s post is all about the term we keep throwing about live prototyping!

- Image showing before and after of prototype 1 | U-TT *

What is live-prototyping?

Live prototyping is a form of applied research that works in dynamic contexts. This means that as designers and researchers, we constantly move between the project site and the research space. Essentially this means developing research that is informed by live work, live action and live feedback for improved real-life impact. Because live-prototyping places a great emphasis on constantly moving between the built environment, where the project is happening, and back to the studio where expert research skills are applied to the context; this form of research can keep up with the flux of social and physical conditions in informal settings. Live-prototyping acknowledges and capitalizes on the kinetic environment of context, in complete antithesis to traditional research that is often static, concrete and not as able to adapt to change. In South Africa, an example of this static approach lies in planning frameworks suited to Western models. Governmental policies such as the Spatial Development Framework follow specific renewal periods, at which stage the plans can be redressed. Policies around building compliance compounded with extreme poverty traps communities in a constant lag behind the system of development.

- Diagram showing current mismatch in community conditions and static research/policy approaches | U-TT

It is often the case that the communities being affected by these plans have fast changing social, economic, and environmental conditions. These sometimes work in conflict to the pace of traditional research. Informality and palpable sprawl in informal settlements are a spatial example of this. We find that this type of research (which is static) is good for analysis but not very effective in transferring active knowledge for broader social benefit. This reveals a critical growing need for new methods of research that are able to respond to the pressing needs of communities living in informality. Dismantling and reworking governmental and academic approaches to begin responding suitably to contexts is a slow and meticulous process in itself. Thus, in the interim, concurrent to that process, we’ve found that live-prototyping gives opportunity to aid in immediate dignified relief for communities in need. More so, live-prototyping focuses on the value of the process and not solely on the product, and in this way gives room for new methodologies to be adopted, adapted and recorded for future re-use. We call this adaptive re-use.

Live-prototyping is a dynamic form of applied research! Through various constant feedback mechanisms - such as interviews, workshops, questionnaires, performance evaluations and collaborative design - we are able to constantly record and qualifiy our research to meet real world contexts. In addition, this has encouraged us to capitalize on the kinetic character of digital tools for planning and participation whilst acting as a tool in prospective sites with similar conditions. We are essentially thinking about how the fourth industrial revolution of data and ease of sharing can be used to the benefit of communities and their physical environments. Steemit is a fine example of spreading and sharing social initiative!

More and more spatial practitioners are using applied research as a means of developing relevant and context-specific design approaches today, particularly in informal environments. Massive Small, Elemental, SDI, Design Space Africa are just a few to mention, driving social projects that respond carefully to the context, and involve community participation as a quintessential informant to the design and process.

- Image: Design Indaba 10 x 10 Sandbag housing, Mitchell's Plein | DesignSpaceAfrica

As we described in our previous post, the EMPOWER project has had three prototype iterations thus far. After each prototype, we are able to see the practicality of the design, and receive live-responses from the community that can improve the next iteration. Again, moving between the built context and the drawing board.

Our design decisions for the second EMPOWER prototype were informed by how the community reacted to the physicality and social opportunity of the verticality in the first prototype. Each prototype allowed us to uncover new approaches and local outlooks that could specify and improve the next iteration. Live-prototyping allows for testing, and feedback from the community, government and policy makers, which ensure that the final design has more real life positive impact in its longevity.

What were these design-decisions and responses that we uncovered and learnt? Well, let us dissect the first prototype design and uncover this applied research together…

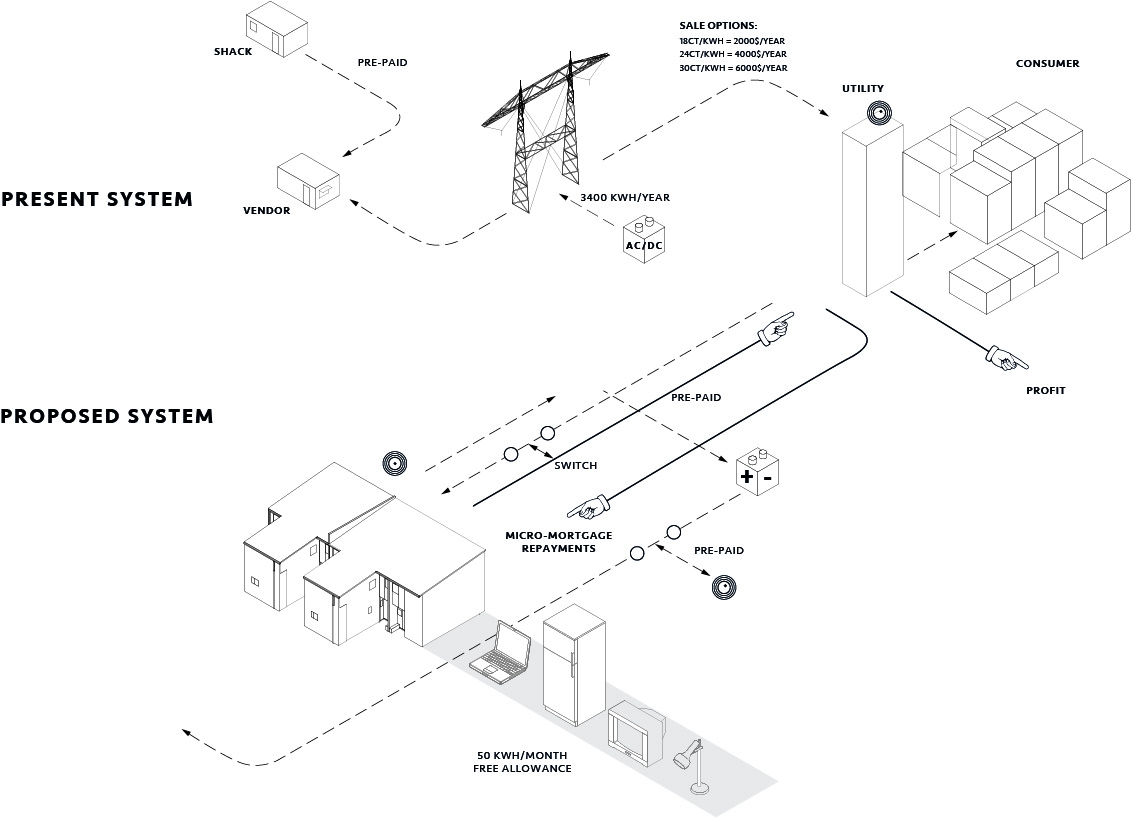

The main imperative behind the EMPOWER project is to provide immediate dignified housing, and so one of the initial explorations in the first prototype involved investigating how to integrate services into structures in a way that did not require a huge reliance on state supply. Our initial research imagined a new model in which the prototype could feature solar technology to both service a gap, while generating additional revenues for residents via government subsidy by feeding surplus energy back into the city grid. The iterative analysis done throughout the project shows clearly that for any unit-based solar component to be viable, the prototype roofs would have to be scaled to a significant level from the beginning to establish an immediate mass. Given the more urgent and achievable goals at hand, we decided to shift the further implementation of solar capacity to that of a first cluster of nineteen houses that could also share Internet and a satellite dish. In response to the fast paced flux of informal settlements and an uncertain future environment, we decided that the Empower prototype would have an integrated roof-PV system, which could be disassembled and reassembled in another location.

- Image of adjusted solar business case | U-TT

Electricity distribution

Evaluating the first prototypes, we were able to witness how residents use the pre-installed electric meter and single point power supply to distribute electricity around their new units. Although the core-and-shell concept stops short of fitting out the unit with full services due to cost, we started a conversation around sharing the electric installation both in terms of labour and cost. The focus turned to the plug-and-play electricity kits for the self-installation of internal electricity distribution. The kits are pre-assembled package of cables, plug points, switches and lights to be plugged in to the distribution board provided by the local energy utility. The lengths and compositions of the pre-assembled components are designed according to the desired lighting and plug layout of each particular house unit. The intention is to remove the need for an electrician on site, and thus to significantly reduce the cost of the electrical installation while provided safe and certified energy distribution.

- Image showing on-site application of electric kit | U-TT

Neighbor preferences

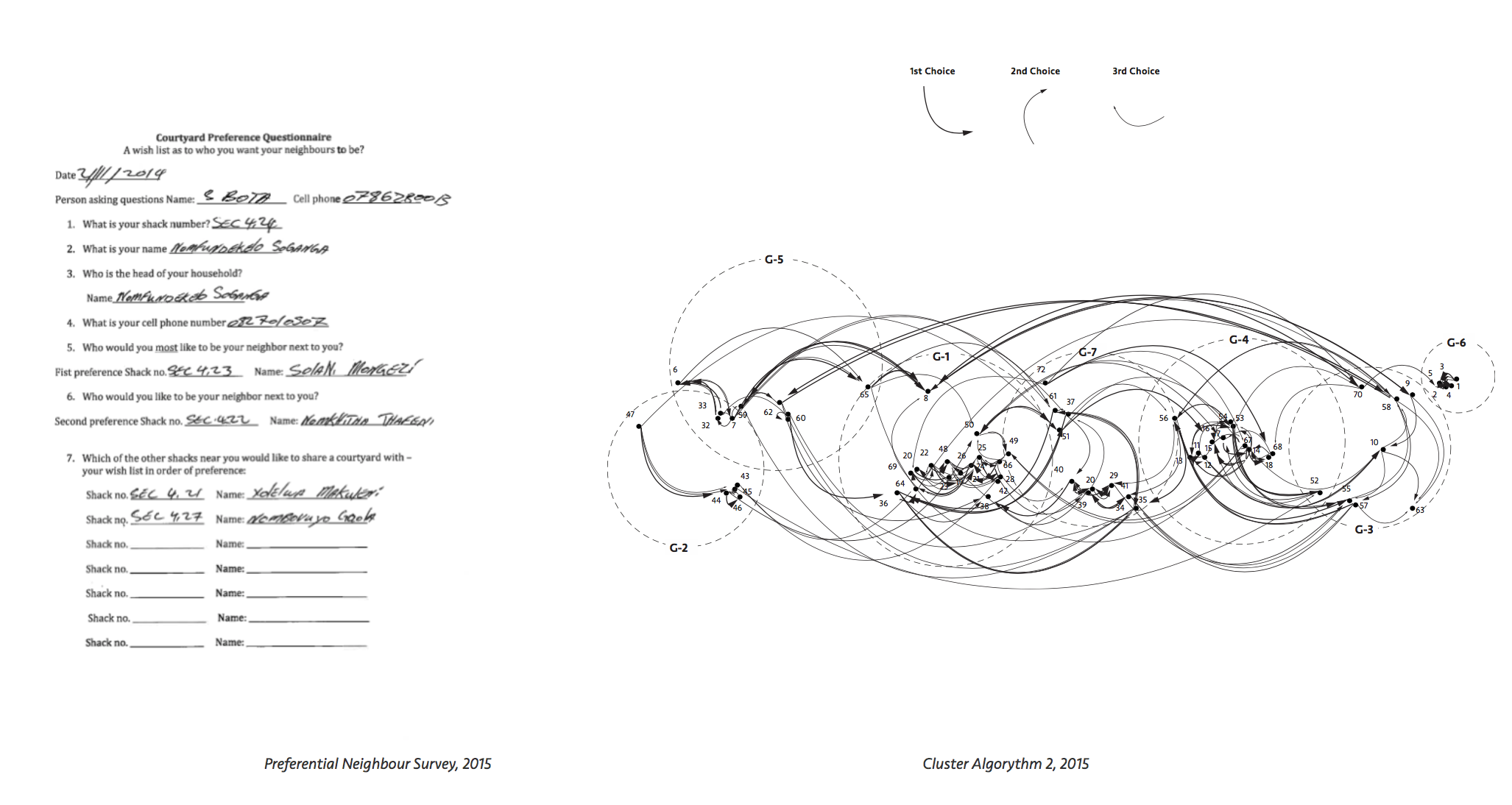

Through discussions and workshops we started to see a network of social cohesion based on neighbor and family trust. By returning to this topic during the design phase we were able to give a spatial dimensions to the theme by suggesting that the new urban layout could indeed reflect this network. After discussions with the community we came up with a survey that allowed residents to choose their neighbours according to preferences. (we will talk later about how we manage this data into a layout with digital tools)

- Image showing neighbor survey in site translated into cluster analysis | U-TT

Evaluation framework

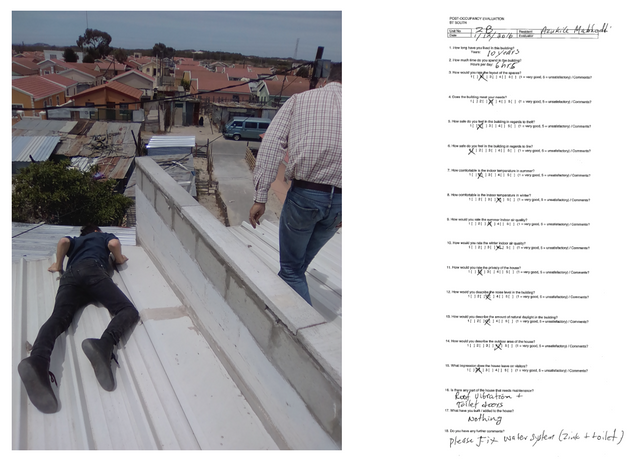

The evaluation framework has been designed to offer insights and measure the impact of the development through themed indicators of the built environment. These indicators include: health and economics, security and value perceptions. They are measured through both multi-choice questionnaires and qualitative structured interviews. The evaluation framework also extends to post-occupancy evaluations, performance quality and impressions from the occupants. For example, results from the post-occupancy evaluation of the first phase of development indicated to us that there had been a clear increase in the perceptions of safety and value to all residents interviewed

- Image showing active post-occupancy evaluation: on-site and on paper | U-TT

Designing with industry

Our team of collaborators initiated research into a light-weight fire-proof partition wall. The design brief required that the wall could match a 50 minute fire rating, possess high sound insulation properties and be quick and easy to install. Many variations for EPS structural insulated panels were explored, these however didn’t offer sufficient density or structural integrity under extreme heat. As a result, our research revealed a material called vermiculite. What an odd sounding material right? In its raw form, vermiculite is extracted from commercial mines in the form of slate like pellets. Under the application of heat, the slate expands to a steady state in an aerated, slightly malleable form. South Africa is the largest miner of the material globally. A local producer V-core use the material to insulate fire-proof doors. A modular wall component system was developed with V-Core and tested for its fire resistant and structural properties.

- Image showing material testing | U-TT

At a distance, through applied research on possibilities for enhanced urban design, we hoped to uncover hidden potentials to refine and expand our approaches and ideas. A key aim of the EMPOWER urban design component is to improve the efficiency of land use in Khayelitsha. We began exploring a clustering strategy that could allow for expansion and effective future land use and tenure. The staircase would act as the centre of a cluster allowing access to the modules and as well as a central courtyard. This way, residents could have the ability to choose a unit suitable to their needs addressing affordability and choice. Additionally, the idea of this central courtyard became a design determinant for the third prototype, which is currently in construction. Through this clustering system we also learnt that clustering happens in a fluid manner in townships, and so when considering strategies for expansion, these clusters would need to account for relationships between community members. This was a factor that played a big role in the next prototypes, where community members came together to decide their neighbor preferences.

- Image showing community drawn enumeration for BT North | U-TT

As a research program and evolving design process, the EMPOWER project constantly seeks to grow and develop. When we look ahead to the next phase of refining the next prototype, we have already seen the catalytic value of doing. Moving between the drawing board and on the ground, live-prototyping as applied research encourages communities to envisage a different urban reality in which they are able to further develop their own environments: a catalyst for agency.

How? Stay tuned for our next post on developing whilst living in dignity, which is what we like to term “Incremental to Compliance”!

- Image showing occupation of second prototype whilst next prototype is developed | U-TT

Get to know about the project at: