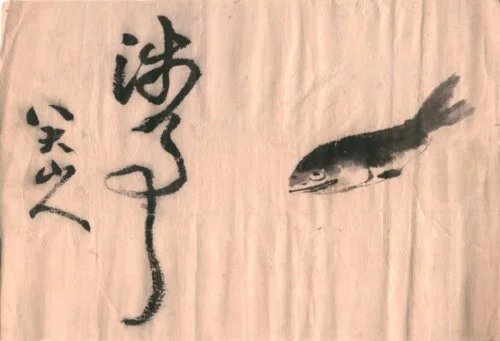

Bada Shanren – Mountain Man of the Eight Greats

Bada Shanren (八大山人; ‘Mountain Man of the Eight Greats’), was born as Zhu Da (朱耷), in 1626 into a family of scholars, poets, and calligraphers – the Yiyang branch of the Ming imperial family, in Nanchang, Jiangxi province, the traditional residence of the Yiyang prince. He was a purported child prodigy and began writing poetry and painting at a very early age. Zhu Da’s childhood was untroubled and idyllic. However the peaceful world of his youth was shattered to pieces by the violent rise of the Manchus.

He was about eighteen years old when the Manchus took over Beijing and nineteen when Manchu forces occupied Nanchang. Three years later, to disguise his identity, as he was a scion of the Ming imperial family, he took refuge in a Buddhist temple after the Manchu conquest and the deaths of his immediate family. The cause or causes of their deaths are still unclear.

Adopting the name Chuanqi, Zhu Da became a Buddhist priest and soon after a respected Buddhist master, quickly attaining the position of abbot. He also became an accomplished poet and painter; his earliest work still in existence is an album of 15 leaves (1659; Taipei, National Palace Museum). He also produced other works under a variety of Buddhist names – Xeuge, Ren’an, Fajue, and Geshan.

In 1672, after the death of his Buddhist master, Abbot Hong Min, Zhu Da gave up solitary monastic life to pursue his fortune as a monk-artist. He joined the coterie of Hu Yitang, magistrate of Linchuan County, and participated in the celebrated poetry parties held in 1679 and 1680. Zhu Da was blocked however in his attempts to take up an official career because of his lineage and in 1680 was devastated by the departure of his patron Hu Yitang.

Reportedly, Zhu Da went mad. One day, laughing and crying uncontrollably, he tore off his priest’s robe and set it on fire. The burning of the robe signaled the end of Zhu Da’s life as a Buddhist monk, and from then on he lived as a painter. Between 1681 and 1684 he called himself lu (‘donkey’ or ‘ass’), a derogatory name for monks, or lu hu (‘donkey house’). During this period of his life, his style of painting and calligraphy changed radically and became far more abstract, a change influenced by the inner turmoil from which he was suffering.

In 1684, he took the biehao (‘artistic name’) Bada Shanren (‘Mountain Man of the Eight Greats’) and lived the rest of his life in Nanchang as an eccentric Taoist hermit. He is alleged to have written the Chinese word – ya (‘dumb’ – unable to speak) – above his door and although he would laugh, cry, drink a great deal of wine and paint, he would not speak with anyone. “When he felt inclined to write,” said one contemporary, “he would bare his arm, grasp his brush, and make cries like those of a madman.”

A staunch Ming loyalist throughout his life, Bada used painting as a means of protest. His works are the poignant voice of the yimin, the “leftover subjects” of the fallen dynasty. As he once wrote; “There are more tears than ink in my paintings.”

Bada Shanren is now widely regarded as the leading painter of the early Qing dynasty. His work has exerted a huge influence on Chinese painting from the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou of the mid-Qing period and the Shanghai School in the late Qing, to modern painters; Wu Changsuo [吴昌硕] (1844-1927), Qi Baishi [齐白石] (1864-1957), and Zhang Daqian [张大千] (1899-1983).

Links:

Websites:

The Bamboo Sea

A Coat for a Monkey

Instagram: @acoatforamonkey

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://labalabamacalli.blogspot.com/2010/01/chinas-art-and-calligraphy.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit