As an art history student just finishing up my degree, I've spent a lot of time in required or survey courses that simply do not interest me. Reading the umpteenth scholarly article defending the restorations on the sistine chapel or crafting a visual analysis of Demoiselles d'Avignon gets really tiring. This semester I had the pleasure of looking deeply at the Mughal Kingdom (1526-1858). The Mughals, though not entirely immune to flaws, self-represented power through visual aesthetics. I wonder how today's global climate might differ if we relied on art to self-position in matters of politics and culture. In the following essay I will address the ways in which one of my favorite Mughal images disseminates a carefully crafted message of both tolerance and total authority.

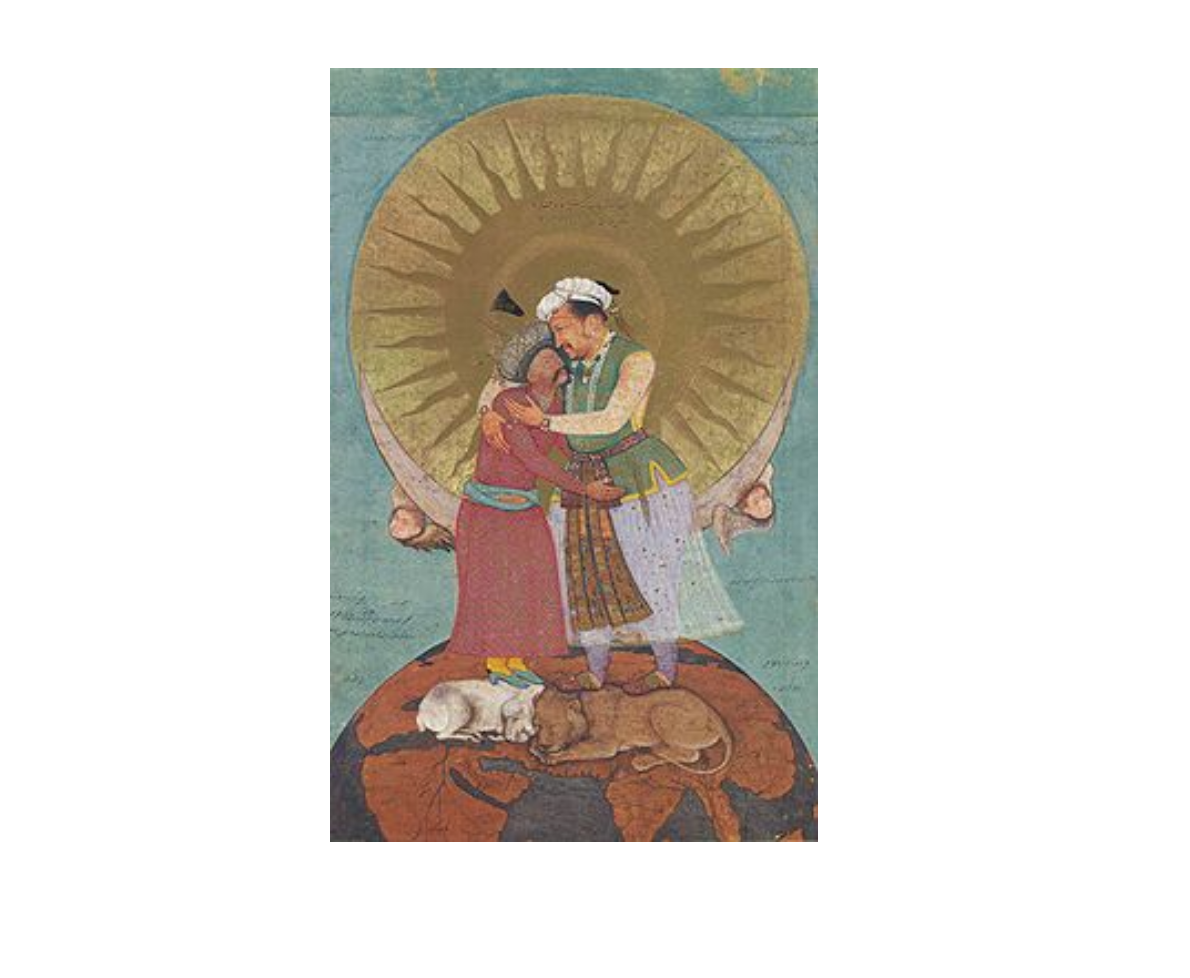

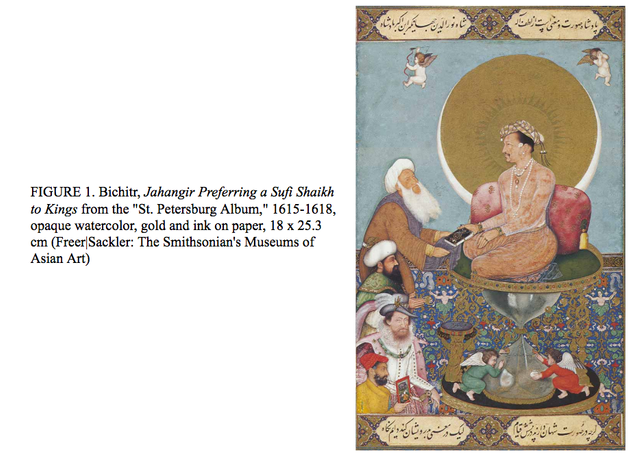

The Mughal Empire (1526-1858) utilized visual aesthetic to inform power while politics symbiotically informed aesthetic. Through a deeply focused mode of visual dissemination, the Mughals carved out a unique style of miniature paintings commissioned from the imperial court to represent autobiographical and historical scenes of rulership. The iconographic, figural, ornamental, and symbolic nature of these visual programs reveal an attitude of tolerance and curiosity towards other cultures while also maintaining a position of total authority over the empire. Mughal Emperor Jahangir employed transculturation to self-fashion himself both spiritually and authoritatively while also maintaining an image of tolerance within the imperial court in the painting Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Saint to Kings (fig. 1) by Bichitr in 1615-1618.

Visual and historical cues can inform the viewer of the nuanced intertwinement of the cultural and political practices of the Mughal Empire. Spatial hierarchy, color choices, pose and gestures, figural, cultural and symbolic iconography amalgamate into a powerful image; one that relays a message of peaceful authority. The strong Sufi-Mughal link illustrated demarcates a strategic relationship that has a rich lineage within the empire. This relationship is clearly prioritized over the Indo-British relationship which is symbolized by King James I. Even so, all of these factors play into Jahangir’s carefully maintained self-representation during one of the most prosperous periods of the Mughal rule.

A striking and unique feature of Mughal court paintings is the small size and remarkable detail. Unlike European courts of the time that boasted large-scale canvas portraiture, the Mughals preferred to show power in the remarkable ability of the human hand to render extraordinary detail. At only 18 x 25.3 cm in size, the precision in the scrolling vegetal ornamentation, jewelry, wardrobe, inscriptions, and figural features—including a miniscule self-portrait of the artist within the painting itself—highlight the talent and artistic devotion of court artisans. This compositional feat is accentuated by vibrant blue and gold colors, often utilized in divine spaces and images.

The scene itself is heavily allegorical. Unlike typical scenes found in imperial namas, or books commissioned by emperors to record and illustrate scenes that have some sort of historical bearing, this image is purely crafted symbolically. Jahangir is seen from a profile view seated on an hourglass throne handing a spiritual text to a Sufi Sheikh. Below the Sheikh is an Ottoman Sultan who is preceded by a depiction of King James I, finally followed by a Hindu holding an image of Bichitr, the court artist who painted the image. Despite what the painting suggests, Jahangir and King James never actually met in person, though British diplomat Sir Thomas Roe serving under King James spent a significant time in fairly intimate proximity of the Emperor during his reign. The image is adorned by playful angelic figures, a direct nod to Christian imagery. Already at least five separate cultures merge into a single scene with Jahangir decorated with gleaming jewelry framed by a glowing nimbus at the epicenter of it all. The rays of the nimbus sun radiate from the King’s head, placing him on the compositional central axis that symbolically leads to the center of a universally reaching sun. Once again, Jahangir places himself in a cosmic realm of divinity while also boasting unwavering diplomatic luminosity.

The Mughal King’s body itself is a political site as Jahangir wears a khil’at, a robe that connotes rank among the royal elite. A translucent fabric drapes over his body, softening his entity with an ephemeral sense of divinity. He is situated in profile, a pose employed frequently in depictions of emperors. This position becomes an idealized standard for Jahangir and creates a psychological distance between him and the viewer. He is both imperially marked as a ruler by this pose while it also functions to situate him in a position of complete integration with the scene around him. In such, a barrier between the viewer and the subject is established while also portraying Jahangir as an accessible figure engaged in discourse with a spiritual guide.

Hierarchy is clearly designated by Jahangir’s position high on the throne above the other figures depicted. The throne, an hourglass, demonstrates the King’s awareness of his own mortality as an earthly being while also nodding toward a spiritual attainment through the message being inscribed by angels at the base of the throne that reads: “O King, may your life continue for a thousand years!” Once again, a duality between earthly, accessible personhood and abstract divinity is established. Jahangir’s body is rendered as a vessel of eternal sanctity that functions to serve earthly purposes of imperial advancement.

The inscription bordering the image plays into this dichotomy as well: “By God’s grace Shah Nuruddin Jahangir son of Akbar Padishah is the monarch of both external form and inner intrinsic mean/ Although outwardly kings stand before him, inwardly he always keeps his gaze upon the poor (dervishes).” Here, the inner self and external self are differentiated—that though figures like King James I may have had some sort of political interaction with the imperial court, Jahangir was devoted first and foremost to God. In this instance, that devotion is represented by the hierarchical prioritization of the Sufi Sheik who is the ultimate subject of Jahangir’s focus.

Sufi-Mughal relations can be traced down a deep lineage, extending back to Amir Timur, a grandfather of the Mughal invasions who embodied Sufi teachings, and reached far into the dynasty with marital alliances and miraculous births. Jahangir had a particularly special relationship to Sufi Sheik Salim. Sheik Salim advised Jahangir’s father Akbar who was also astutely interested in mysticism. Sheik Salim’s following was just as much Hindu as it was Muslim, making him more than a beneficial personal advisor—he also functioned as a political throughway. Salim acted as a crucial intermediary for Mughal expansion. He was so influential among the existing population that Akbar chose to position Fatehphur Sikri, his new capital city, in Agra--Salim’s hometown. Sheik Salim would persist to serve another vital role in the development of Mughal politics; Akbar was unable to conceive a male heir to the throne until Salim interceded. It is believed that Salim was largely responsible for Jahangir’s eventual birth—who was originally named after the miraculous Sheik before later becoming Jahangir.

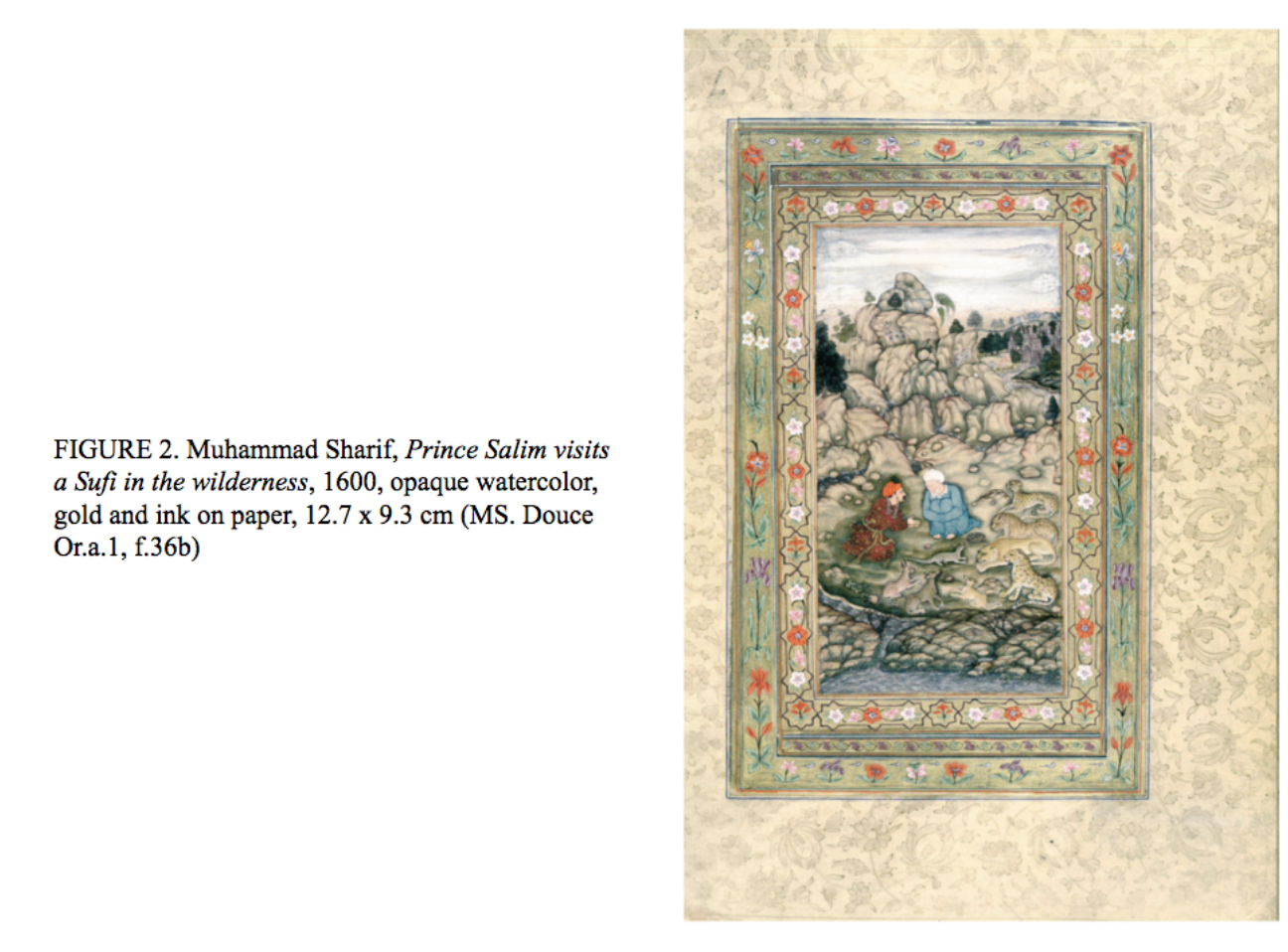

Prince Salim Visits a Sufi in the Wilderness (fig. 2) painted in 1600 by Muhammad Sharif depicts Jahangir (previously known as Prince Salim) conversing with Sheik Salim in the secluded wilderness. Here a notable attitude of supplication is rendered through the Prince’s kneeling position. An assembly of fierce animals surrounds the conversing Prince and Sheik; while the lions, leopards, and cheetahs are archetypal symbols of danger and strength, they maintain docile faces—another indication of the tolerant yet commanding image the Mughals self-perpetuated.

To further the Sufi connection, Jahangir’s own wife, Jaharnara was highly ranked within a Sufi order and held a leading role in Sufi-Mughal relations during her husband’s reign. With these deeply intimate familial ties as well as the vast political advantages of allying with the Sufis, it is clear why Jahangir would position the Sheik at near-equal level with him. Both Akbar and Jahangir were known to self-fashion portraits with saintly figures to elevate their own divine image. The greater binary between legal and mystical institutions in Islamic governance becomes more and more indistinct.

Besides Jahangir’s relationship to the Sufi Sheik, the three other figures also contribute to fashioning an image of an expansive empire. The Ottoman Sultan and Hindu figures straightforwardly connote religious and geographical alliances. The image of King James, on the other hand, serves a more complex purpose. While Jahangir never came in direct contact with King James himself, Sir. Thomas Roe, an English emissary, forged a relationship with the Mughal court over the course of the Emperor's reign. The classically European rendering of King James, indicated by his wardrobe, facial features and pose, was likely directly copied by a painting that was probably presented to the court by Sir Thomas Roe.

This integration of European images in Mughal visual arts is a tradition that first flourished under Akbar’s rule. He had taken on a keen interest in Western arts and religion and held courtly sessions with Portuguese Jesuits who brought him paintings and scripture in hopes of conversion. Jahangir carried on this tradition and utilized images brought to his courts by Jesuits to integrate into his own school of Mughal painting. Not only do we see this evident in the inclusion of King James, but also nods to Christianity are clearly marked by the angels flanking the nimbus and at the base of the Jahangir’s throne. These symbols were not employed to display Jahangir as a practicing Christian; rather they serve to show sophisticated curiosity and education within the Mughal court towards Western cultures and religious structures--nothing was out of reach.

While Sir Thomas Roe was sent to get footing in the court to gain traction for what would eventually evolve into full-fledged colonization, at this point Britain was not seen as a serious threat. Jahangir and Roe had a significant relationship that might have signified some semblance of trust between the two empires. Even so, the portrayal of King James places him low on the hierarchical ranking of figures as well as situating him in submissive kneeling position. Unlike the other three figures who either face profile or are directly engaged with Jahangir, King James faces outwards from the ruler in three quarter view connoting low rank and demonstrating a distance and inaccessibility to Jahangir and the Mughal Empire.

This dynamic once again emphasizes the dichotomy of power and tolerance, inward and outward, spiritual and political. Power is aestheticized in this image with the intention to leverage a carefully crafted portrait of Jahangir and his expansive empire. The arts were assigned a deeply political role to lend force in imperial authority. Yet Jahangir in actuality was not the stable, spiritually endowed ruler he sought to portray. While he enjoyed abundant amounts of riches and prosperity, he also indulged in copious amount of opiate and wine consumption. This personal instability was aggravated by hostility from his son, which might have disturbed confidence in morale and constitution of selfhood. In such, the need to self-fashion as somewhat of an abstract divine entity was imperative for maintaining public image.

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Saint to Kings (fig. 1) presents an allegorical scene that carefully integrates the visual and the political to craft an image of duality: an Empire founded in unity and tolerance that is simultaneously wholly commanding over nearby and far off cultural and political influences. While Jahangir might not have lived these ideals personally, the malleable nature of visual representation was able to aesthetically present a person of vast power worth admiration and submission.

Congratulations @glamdoll! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit