EPISODE 1: DEAD MAN

Released in 1995 Dead Man was made for $9MM, a hefty budget for Jim Jarmusch, one of the primary figureheads of independent filmmaking at the time. It failed to find its market however, managing just $1MM at the US box office and receiving more than one poor review, with renowned critic Roger Ebert commenting, “Jim Jarmusch is trying to get at something here, and I don’t have a clue what it is.” It took another ten years for Jarmusch to get his hands on a comparable budget (Broken Flowers) and he’s never helmed anything as expensive since.

The film stars a pretty faced Johnny Depp and we have to give him props too, for his surprising choices during this period, which point to an actor valuing artistic merit, unusual story lines and the opportunity to develop his craft over the elephant sized productions that he is now best known for. After a 3-year commitment to TV teen drama 21 Jump Street, which he called pointless, Depp spent the entire 1990s, seemingly going out of his way to choose oddball roles in back to back box office flops such as What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, Arizona Dream and Ed Wood. Consequently, there are any number of weird and wonderful Depp films I could have chosen for this post — yet Dead Man tops them all as being particularly brilliant but criminally under-appreciated.

*****WARNING SPOILERS ALL THE WAY THROUGH*****

Sometimes it is preferable not to travel with a dead man

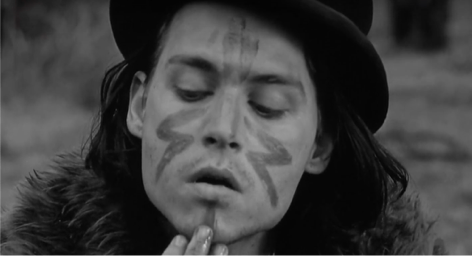

Dead Man is a dreamlike Western shot in stunning black & white. Depp stars as William Blake (not quite the famed English poet, more on that later), a young accountant from Cleveland who sells everything he owns after his parent’s funeral to pay for a much derided checker patterned suit and oneway train ticket to the frontier town of Machine where an accounting job supposedly awaits him in Dickinson Metal Works. However Machine is the “end of the line” and by all accounts the end of civilisation too. Jarmusch makes sure the audience gets this with Blake’s opening train journey, which he spends napping, reading 19th century Reader’s Digest and gazing out the window at the dramatic and ever changing landscape. Occasionally he turns his gaze towards his fellow passengers, each time finding a new set of train riders who grow more and more rugged the deeper he gets into the American wilderness until finally, Blake finds himself alone in a carriage full of hard liquor swigging, big beard growing, hairy animal skin wearing mountain men. At this point his scary looking fellow passengers slide open the windows and begin blasting their rifles. They are shooting buffalo, not for meat, fur or even sport but to support the ongoing destruction of ‘hostiles’, an unofficial but aggressively pursued army war tactic best summed up by one Colonel Dodge in his infamous 1867 statement, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone”. Conservative estimates place the number of buffalo slaughtered in this way at 30 million and Jarmusch displays his superior directing chops by highlighting the US government’s extermination policy against the ‘plains Indians’ in an absurd yet matter of fact style.

Welcome to hell: town of Machine

Accompanied by a bad ass sound track consisting of Neil Young ripping eerie, distorted rifts on electric guitar, Blake descends with the mountain men at the end of the line and wonders through the wild west town of Machine. But this is like no wild west town you’ve ever seen; lost pigs, ankle deep mud and horses pissing are some of the sights and sounds that assault Blake, shot in a tracking point of view style that lets us walk in his shoes. A hooker gives a furious blowjob in an alleyway to a shaggy client who aims his six-shooter at a shocked Blake, encouraging him to move on. Unsmiling frontier people stand still as they survey the out-of-towner and Jarmusch effortlessly creates a series of wild west portraits as Blake reaches Dickinson Metal Works. Imposing and smoke billowing the factory is an indication that despite the drying animal skins, livestock and old saloon bars a new American industrial age is coming. Dickinson Metal Works is also perhaps, an indicator of hell, the workers toiling inside, condemned souls and Mister Dickinson the devil himself. But if the metal works are symbolic of hell, why has Blake journeyed there? Could it be that he himself has a dark past, some heinous crime he committed back in Cleveland which explains why he has gone as far out west as possible in an attempt to escape and begin afresh? Did he murder his own fiancee when she, “Changed her mind?” Jarmusch never tells us explicitly but sprinkles many clues that this may indeed be so. Clue number one when he reaches the factory is the office manager’s — played by a brilliantly incredulous John Hurt - inability to pronounce Blake’s name, instead repeatedly calling him “Mister Black,” despite Blake’s attempt to correct him. And his promised job is gone, awarded to somebody else, despite Blake’s confirmation letter. Nothing is solid, everything fluid and ever-changing like a dream, a dream of death.

Mr Dickinson: the devil?

Blake demands to speak with Mister Dickinson whereupon the office erupts into laughter. Clearly this is not advisable but Blake insists and finds himself in an empty room with no one but a stuffed and erect grizzly bear for company. Suddenly a deranged Robert Mitchum (his final movie) appears from nowhere, like the devil himself, though he may have been crouching behind his desk, and for the second time in Machine, Blake finds himself in the sights of a firearm, this one a long double barrelled affair. After cursing his “ridiculous clown suit,” Dickinson confirms that the only job awaiting Blake is one involving, “pushing up daisies in a pine box”. Blake makes a speedy and humiliated exit and now at an utter loss as night time envelops, spends his final coin on a small bottle of whisky. His luck seems to turn when he meets a pretty, ex-prostitute and elopes with the youngster in her 19th century bedsit. But they are interrupted by her unhinged lover (Gabriel Byrne) and for the third time in one day, Blake finds himself in the cross hairs of a gun. This time the guns go off, the girl is shot dead with the bullet passing through her heart and landing in Blake’s own chest. Despite this, Blake manages to shoot the killer at the third time of trying, jump out the first-floor window, steal his horse and gallop into the night — and it is here that the movie really begins.

Did you kill the white man who killed you?

However, this is far from a conventional Western with a proactive lead character on a definite mission complete with plot tension. Blake doesn’t really seem to know what he wants or care about where he is going. He simply follows a character called Nobody (Gary Farmer), an obese, tribe-less and profoundly eccentric native American who finds Blake blacked out in the wilds and attempts to dislodge the bullet in his chest. But he can’t remove it, the bullet is too close to his heart and Nobody asks Blake if he “killed the white man who killed you”. On the surface, Blake is clearly injured but is it fatal? Nobody has no doubt it is and upon learning Blake’s first name is William he mistakes the bemused accountant from Cleveland with the visionary but very dead poet and takes it upon himself to guide Blake on a spiritual journey to the ends of the earth, where he will take his final journey across the seas to the afterlife. Blake seems to go along with the plan, if for no other reason than he is mostly semi conscious and just hanging on to his life anyway. But perhaps he also senses it is his destiny and a journey he must take to find redemption and atone for his sins in Cleveland, whatever they may be. It is here the film takes a decided turn for the hallucinogenic with disorientated POV shots from Blake’s stolen horse, the irregular feather headdress of his spiritual guide before him and epic mountains swaying in the distance while Neil Young’s haunting guitar lingers on a single distorted note. Nobody does actually heal Blake, though this is more of a temporary fix to ensure he has the strength to reach the North West Pacific coast, and the procedure takes place with melodic native Indian prayer while Nobody rubs the blessed clay over Blake’s bullet wound. Jarmusch ensures things don’t get too sentimental here with Nobody calling Blake a, “Stupid fucking white man” before continuing his sacred singing. In fact most of the film is peppered with Nobody’s colourful language regarding white men. At one point he states that Blake is being followed. How does he know? “Often the evil stench of white men proceeds him” is the reply. Is this racist? Certainly it is, but in the context of a campaign of genocide against his native brethren, which Jarmusch highlights several more times, Nobody’s observations will offend only the most thin skinned and uncomprehending of viewers.

Goldilocks and the three bears: a test for William Blake

The surreal nature of Blake’s journey is furthered by Nobody’s indecipherable ‘Indian talk’ and while Blake has little to say for himself apart from things like, “Erm, shouldn’t you be with your tribe or something?” Nobody, by contrast, is forever making statements such as, “The round stones beneath the earth have spoken through the fire” and, “Things which are alike in nature, grow to look alike and the speaking stones have lain a long time looking up at the sun.” Likewise, Nobody’s actions are often seemingly illogical. At one point they spot a group of animal trappers, including Billy Bob Thornton in a big bear coat, (which Blake later liberates for himself), and a hilarious Iggy Pop decked out in filthy Little Bo Peep Hat and skirts. Nobody insists that Blake “go down to them” alone. Blake is horrified by the idea, pointing out that they don’t look very friendly and could kill him. But Nobody states that it is a test and proceeding around the white men, thus avoiding them is out of the question. But there is a logic to Nobody’s method. That they have come across this weird and wild, young-man-hungry group in the woods is no coincidence but Blake’s fate, generated by the Great Spirit for the purpose of challenging him and thus assisting his spiritual growth. Blake must shed his philistine soul and accept the Indian ways if he is to have any chance of redemption and be worthy of the Great Spirit’s blessings.

A transformation

Although on the face of things, a decidedly passive character, Blake does occasionally offer weak resistance to Nobody’s Indian approach, significantly when he spots his own wanted poster and throws a temper tantrum when he reads that he is not only wanted for the murder of the jealous lover but also for the man’s fiancee, which it turns out is the ex-prostitute. Is this another clue from Jarmusch that though Blake was not the shooter of women in Machine perhaps something awful did happen back in Cleveland? Nobody certainly appears unconvinced by Blake’s protestations, perhaps disappointed with Blake’s failure to come to terms with his own past. When he remarks, “You cannot stop the clocks by the building of a ship,” Blake finally snaps, admitting that he hasn’t understood a single word of Nobody’s their whole time together and that he’s, “had it up to here with this Indian malarky”. And neither is this a straightforward buddy journey. After digesting peyote, halfway through the film, Nobody rather randomly decides that the time has come to separate and rides off wearing Blake’s eye glasses with final words of advise that perhaps Blake will “see better without them”. After all, Nobody is merely Blake’s sometime spiritual guide, not his father, and Blake has to figure out some of this shit on his own. Food and sleep deprived, Blake wonders on through the forests by himself, observing the death of men and animals and doing a little killing of his own. At one point he lies down to sleep, cradling a dead little Bambi dear, also shot through the heart. Is this further proof of his dark past? And is he learning anything? We’re not entirely sure but some inner changes are evidently under way and when destiny reunites him with Nobody, Blake feels like he has once and for all shed his repressed accountant skin and transformed into… something else.

Finger licking good: does Cole Wilson represent Blake’s dark side?

The plot, such as it is, revolves around the fact that the man Blake shot back in Machine was actually Dickinson’s only son. Consequently a $500 bounty is placed on his head with competing groups of desperados on his tracks, most dangerous of all, a group of three infamous bounty hunters who have already received a preliminary payment in gold. But there is more comedy than suspense here, with the ringleader Cole Wilson (an admittedly terrifying Lance Henriksen) eventually killing and eating his two fellow companions. Wilson is a godless barbarian the direct opposite of Nobody and perhaps representative of the darkness of Blake’s being while Nobody represents the light.

Ready for a new start, but did he learn anything?

As they proceed to their destination and the giant canoe builders of the Haida nation, Blake racks up his own kill score of bounty hunters, law men, possum skinners, unscrupulous missionaries and jealous lovers with a final body count of six, two shy of Billy the Kid’s eight — for those of you interested in the mythical outlaws of yesteryear. Killing white men appears to be part of Blake’s spiritual growth with Nobody observing that the gun “will replace your tongue, you will learn to speak through it and your poetry will now be written in blood.” But in the accumulation of shootouts, Blake collects more “white man’s metal” in his weak body so that by the time Nobody places him within his sacred canoe and pushes him out to the ocean, Blake is well and truly dying. But was his spiritual learning curve successful and will he be accepted into the after life? Only Blake knows but a final tragic scene, observed by William Blake as he floats away, of Wilson and Nobody simultaneously shooting each other dead seem to confirm the end of his human duality and his readiness to enter the world of the spirits.

Now doesn’t that sound like a great movie? I’m not sure how much justice I’ve done it but Dead Man is a truly remarkable and moving cinematic experience, even on a lap top. First rate cast aside, Dead Man is rich in dark humour, visual poetry and homage to the lost cultures of the native Americans. And for the record, despite it’s dreamlike characteristics, Dead Man simultaneously presents an uncompromising kind of realism, a non-sentimental and non-Hollywood version of the old frontier, very much absent in most glossy Westerns since. I urge you all to buy or rent it and join it’s ever growing band of cult followers.

Congratulations @herengels! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I didn't know it lost money. It was a great movie. And I am kind of sure it made more than its budget in the long run.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hope it did but typically the director's commercial value will be determined from returns during the first year

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

well.... neither of us care about the commercial value of a director do we? :D

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

he he true! I guess it affects their opportunity to direct more movies, which is why we should savour Dead Man ;)

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @herengels! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @herengels! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit