On June 9, 1311, work stopped in the Italian city of Siena. Traders did not go to the market nor did artisans open their workshops. From very early on, an air of party circulated through the streets. At one point, the cathedral bells rang out their voices. And a chorus of trumpets and drums answered the call. Clergy and Signoria took their place at the head of the parade that was about to begin. It was an unusual procession: the crosses that the priests carried formed wings for a great complex and beautiful work of art – the Maestá.

Still incomplete, it was transported to the cathedral, on whose high altar it would remain for almost 200 years. It will take 32 months of work and cost 3,000 gold florins, but the people who are now witnessing its passing know that its value is priceless. It's a masterpiece. The best that Siena – devout and sensitive – could bestow on the Virgin and her four patron saints. People only have eyes for the beauty of images. Few are those who even notice the inscription at the foot of the throne of Our Lady:

Holy Mother of God - be the cause of the old man's repose - be the guide of life - because he painted you thus.

Holy Mother of God, grant peace to Siena, grant life to Duccio, for this is how he painted you.

It's a proud inscription, but Duccio di Buonisegna had reason to be proud. From his studio in San Quirico, near Porta Stalloreggi, the creation that had mobilized all the wealth of his talent, the most important work of his artistic career, had just emerged. He'd done it alone, or with some help from outsiders. In his late 60s, he possessed considerable wealth and the recognition of his own. The fortune, he himself will take care of dissipating it in a short time. But the recognition will persist to this day, although there is little information about his art history.

The name Duccio di Buonisegna appears for the first time in 1278 on a receipt for 40 soldi, which the Municipality of Siena paid him for the decoration of twelve chests for the official archive. The paper proves that in that year Duccio was of legal age. On the other hand, the work referred to – more artisanal than strictly artistic – was usually performed by artists who, enjoying some prestige, were, however, young at the beginning of their careers. Such considerations make historians assume that in 1278 he must have been about 20 years old, that is, he would have been born between 1255 and 1260.

Another document, from 1279, reports that Duccio received 10 sous as payment for decorating the cover of a record book. As early as 1280, however, the artist’s historical current account shows a debt: he is fined 100 lire for an unspecified offense – the first of a long series of punishments, perhaps evidence of a restless, rebellious temperament prone to misconduct. , more or less serious in the eyes of Sienese law.

In 1285, Duccio signed a contract with the fraternity of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence, to execute a painting of the Virgin, now safely identified as the Rucellai Madonna by the same author. For this work, Duccio received 150 florins. Still in 1285, the painter returned to Siena and to the decoration of book covers, an activity that he would also dedicate himself to in 1286, 1291, 1293 and 1295, charging in each case 8 or 10 sous. As for his private life during this period, it is known that in 1292 he owned a house in Via di Camporeggio, that in 1294 he lent 33 sols and 6 monies to someone and that in the same year he acquired a vineyard – facts that show a certain prosperity.

In addition to prosperity and popularity; in 1295 he was asked to give his opinion, together with other renowned artists, on the ideal location of a new fountain. Even so, he was not fined months later for unknown reasons. Three years later, he was a member of Radota, a sort of advisory committee of the municipal council. Nevertheless, history discovers him in the following years refusing to swear allegiance to Pacitano del Popolo, chief magistrate of Siena. The Capitano's revenge comes in 1302: he makes Duccio pay a fine of 18 lira and 10 sous for not having participated in the war that Siena waged against the city of Maremma, and soon after another, of 15 lire for causing a disturbance in the square. public.

The artist's finances suffer not only from political or administrative penalties: three times in 1302 – in April, May and December – he was fined 5 lire for failure to pay various debts, although that same December he received 48 lire for a canvas with a predella. to the altar of the inner chapel of the Public Palace. (The work was lost)

Two years later, Duccio is mentioned as the owner of a “mountain of vineyards” in Castagneto, near Siena, a sign that the painter's budget will not be too shaken by the usual punishments. Its resources would strengthen even more from October 9, 1308, the date on which it signs the contract to carry out the Maestá. Just to execute the part of the painting that shows the Virgin surrounded by a court of angels and saints, it was stipulated that he would receive 16 daily wages. In addition, he would have a monthly salary of 10 lire. As if these figures were not enough, the city's records note that an advance of 50 gold florins was immediately made to him.

In the course of the following, the remaining specifications of the panel were revised. It was then that it was decided to paint it on both sides, although the existing contract to date is not very clear in this regard. The pay table was changed to two and a half gold florins each panel, with 26 divisions plus 8 twice the size in the predela. In all, Duccio would be paid for 38 separate scenes.

On November 28, 1310, the painter is rushed to finish the work as soon as possible. On June 9, 1311, the work is festively inaugurated. The day before the second anniversary of the inauguration – according to a document of this date – Duccio was again buried in debt. From them he will never get rid of them: when he died, in 1319, he was in a state of total insolvency. The reason why the widow Taviana and her seven children refused the inheritance that was theirs.

It is curious to note the abyss that separates Duccio's personal conduct and art: while the former is characterized, by all indications, by indiscipline and dissipation, his paintings are calm and dispassionate. They are unaware of strong emotions, emotional outbursts or any sense of tragedy. The spiritual conception that is revealed in his works is subtle, lyrical, aristocratic, stripped of drama. The effect they aim for is decorative. And the technique is evidently refined.

Duccio is the Italian version of Byzantium art. This means that it is situated in the area of the aesthetic influence exerted by Constantinople on Italian painting, in particular, Siamese, from the 13th century. And that means he knew how to recreate the Byzantine way with Western eyes. He took from Byzantium the taste for decorative effects and the care in the making of details, but he replaced the austerity that characterizes the figures of Oriental art with a graceful malincholy, typically Italian. In almost all of his creations, the Gothic spirit of the design is no less present than the Byzantine gold ornaments on the characters' clothing.

It is to Duccio that we owe the realistic treatment of details – a distinctive feature of the 14th century Siamese school – but, in terms of the delineation of human forms, he appears to be much more conventional – and oriental – than, for example, a Giotto. Likewise, when painting the interior of a room, Duccio does not reach the richness of the other's perspective. On the contrary, one can sometimes notice a lack of proportion between the different parts and the composition as a whole.

In Giotto the composition is simple: so much attention is paid to the actors in the drama, that the accessory figures seem neglected, hidden in a corner, just emerging their clustered heads as a sign of presence and nothing more. In Duccio, the distribution of characters is much more uniform: more important and less important figures are little different. Its location in the frame does not obey the principle of making the narration comprehensible – as in Giotto – but the aesthetic needs of a general balance in the composition. Giotto wants to tell a story. Duccio wants to paint a beautiful picture. In the same way that the miniaturists of Constantinople methodically worked their illuminations devoid of emotions – only in search of form and beauty – Duccio produced canvases in which there was no place for the element of passion,

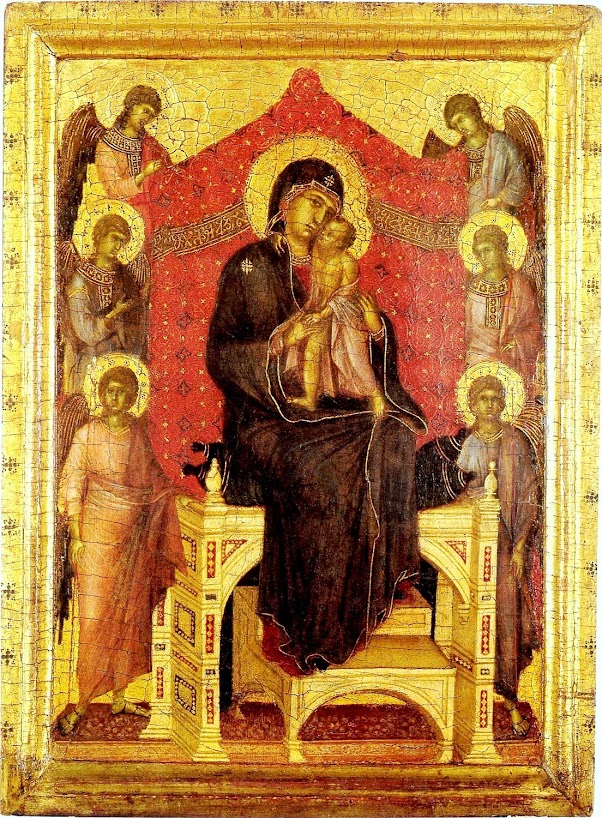

See, for example, the Madonna Rucellai, or Our Lady on the Throne with the Child and Six Angels:

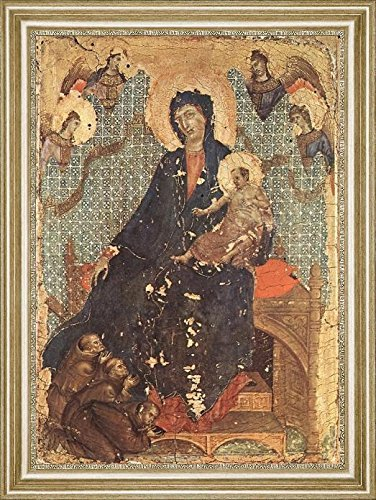

it is, in the words of several critics, one of the most important paintings in the history of Italian art. For centuries it was attributed to Cimabue, the Florentine who was Giotto's master, and, although it does have elements of his own style, it denotes a Siamese language like that of Duccio. Just look at the expression of the Virgin and the angels, soft, mystical and languorous. And just compare the work to the other. – Our Lady with the Child and Two Angels,

whose author is indisputably Duccio. The similarity between the two Madonnas leaves little room for doubt: both paintings were produced by the same artist, at more or less the same time. Both resume the Byzantine tradition, without leaving – of course – the cultural horizon of Italy.

The same can be said of the small but magnificent Nossa Senhora do Trono, known as Nossa Senhora dos Franciscanos.

It is in this painting that one can clearly see the link between Duccio's language and that of the Sienese artists of the previous generation: in the quality of his technique is the sophisticated Italo-Byzantine manner that flourished in Siena at the end of the thirteenth century. Meanwhile, the work reveals some important innovations. The figure of Our Lady, for example, described with a sense of graceful and gentle humanity, without any solemn or majestic spirit, reflects a new conception, hitherto unknown in the Sienese school. But the fundamental difference between Duccio's art and the traditional Italo-Byzantine style lies in the introduction of Gothic elements into the design: here lies a very personal contribution by Duccio, as he could not have borrowed it from any of his predecessors, whether in Siena or Florence.

Duccio's artistic activity around 1300 is partially recorded by a group of canvases currently dispersed in several museums in Europe. Among these is Our Lady of the Throne with the Child and Six Angels, in the Kunstmuseum in Bern,

whose attribution to Duccio was proposed for the first time in 1930. As a vague memory, Cimabue's language survives in some points - in the arrangement of the angels, in the gesture of the Boy - but what predominates without a shadow of a doubt is the Gothic modulation of the lines.

Such works mark the transition to Maestá, Duccio's most famous work. What we see today does not correspond in terms of its construction to the original that left the artist's studio on that famous June 9, 1311 and was dismembered in 1711. Painted on both sides, it showed, on the front, Our Lady on the throne with the Child, surrounded by her heavenly court of saints and angels; kneeling at her feet, the patron saints of Siena - Ansano, Savino, Vittorio, and Crescentius. On the back was a representation of the life of Jesus. Each side of the panel had a predella. The Virgin's predella was composed, on the one hand, of the scenes of the Annunciation, Nativity, Adoration, Presentation in the Temple, Massacre of the Innocents, Flight into Egypt and Christ the Child Teaching in the Temple; on the other hand, Baptism, Temptation, the Call of Saint Peter and Saint Andrew, the Transfiguration and Resurrection of Lazarus. The predella scenes were divided by small panels containing the figure of a prophet or a saint. Above each large panel, the various appearances of Christ after the Resurrection, and a sequence of scenes illustrating the death of the Virgin.

In addition to the large painting on the front panel, Maestá comprised around 60 independent illustrations. After the two sides of the work were separated, five of those were lost, eight dispersed outside Italy – three in Washington, two in London, three in private collections in New York. The others can currently be seen in the museum of the Cathedral of Siena.

The front of the composition, the one showing Our Lady on the Throne,

reveals a profound sense of symmetry: each angel and saint on one side has its counterpart on the other, though separately each figure has a freedom of its own vis-a-vis the others. In none of them will it be possible to find any trace of rigidity.

Figures VIII and X reproduce two details of the Maestá front panel. The first is the portrait of Saint Ansano, located to the right of the Virgin. Like three other patrons of Siena, his attitude is that of one who intercedes for the city. Depicting these saints in genuflection, unlike all the other characters, Duccio distinguishes them in order to differentiate between the heavenly world and the earthly world.

Santa Cataria of Alexandria is the figure of figure X. In the classic purity of his lines, critics discover another proof of Duccio's taste for Hellenic painting. Here, the Greek tradition is combined with a pious feeling of humanity, expressed above all in the sweetness of the look, turned in adoration – like that of all the characters – to Our Lady.

With the Annunciation (figure 5) begins the narrative of the life of Jesus, told by Duccio most of the time in the version of the Gospel According to Saint Matthew. The scene has an excellent architecture in the background, from whose projection on the left emerges the messenger of God blessing the Virgin with his right hand understood; under a large arch, she receives him by raising her left hand to her chest, in an attitude of reserve, while in the other she holds a book. In the background, between both figures, a vase of lilies – signifying purity.

The Entry into Jerusalem (figure XII) begins the cycle of the Passion. Faithful to the Gospel of Saint Matthew, Duccio represents Christ arriving in the city on the back of a donkey; several of his apostles follow him. The crowd awaits him outside the wall; many people hold a branch in their hands and some, more agile, go to look for them in the trees. Of the city itself only one or two buildings appear.

In turn, the Crucifixion (figure XIII) occupies the center of the panel, according to Byzantine tradition, it is almost four times larger than the scenes on the left and right (see pages 3 and 5). Christ's dead body hangs from the cross very high, his arms – somewhat too long – attached to the ends. On a slightly lower level, the crucified thieves. Fat drops of blood flow from the wounds of the three. Above the larger cross, thirteen little angels express their deep pain in a variety of gestures; two of them seem to kiss the hands of Christ. At the foot of the petitioners, two groups of people, the one on the left less compact. In the foreground, still in the group on the left, Our Lady faints in the arms of two companions, her hands held by Saint John. The group on the right is violently agitated,

As a whole, it is impressive and is distinguished in Duccio's artistic output by the absence of the usual placidity. It is also noted in another sense: Duccio, who generally liked to paint his seines to the last detail, preferred here to privilege the general effect of the composition and the balance between the figures, omitting, for example, the soldiers who dispute the clothes in the game. of Jesus as they appear in the narrative. More than one critic judges this crucifixion to be Duccio's masterpiece.

The scenes of Christ's appearance after the Resurrection seem to have been painted with less care. So much so, that certain critics even attributed it to 'disciples' of Duccio – a hypothesis, however, not very plausible, given the inexistence of any document on the subject. The Apparition at the Lake of Tiberias (figure XIV/XV) follows the text of the Gospel of John and closely resembles another painting of the same work, the one depicting Christ instructing the apostles about their mission. Of the seven apostles mentioned in the aforementioned text, Saint Peter appears walking on the water, his hands extended towards the Savior, while four of the six in the boat look at Christ and two dedicate themselves with all their strength to removing the net loaded with fish.

The crowning of the Maestá comprises the illustrations of the last days of Our Lady's life, after the death of Jesus. The sequence represents, among other scenes, that of the miraculous visit of the apostles to the house of Mary, to which she had expressed the desire to see them before she died. From this episode, he reproduces in figure XI the moment when John kneels before the Virgin, in a quiet and affectionate farewell. The stooped posture of the characters reflects the sense of intimacy with which Duccio wanted to characterize the encounter.

The Death of Mary shows Christ in the center before his mother's bed.

In her hands, the miniature that personifies the soul of Our Lady. On each side is a cherub. Behind, on the left, three angels; two on the right. In another plane, a row of eight angels and two cherubs. Nine apostles remain at the foot of the bed, while two others kneel.

Not to mention the lost illustrations, the work comes to an end with funerals and the burial of Our Lady. What is certainly missing are the scenes of the Assumption and Coronation. Critics concede that the last one in particular must have looked like the one in the triptych, now in Buckinghan Palace, London. If this triptych is really by Duccio - as is supposed -, it must be placed among his last creations, in view of the undeniable differences it exhibits in relation to the other works he left behind. In any case, Duccio's trajectory seems substantially complete with a gift to Maestá – with which he managed to reach the apex of his lyrical and serene production.