Girl with a Pearl Earring

The life of the girl

There has been much speculation about who was the young lady of the pearl, but in this article we will not try to clear that question. Nor will we focus on the figure of the father of the creature, also wrapped in a halo of mystery. Vermeer, one of the most admired painters of the seventeenth century, did not have such a reputation in his time and was an unprofessional painter. At least that is what indicates the limited number of works (34 recognized) that have reached our days. In the following lines we will focus exclusively on his most famous creation, hence we are interested to know what happened to her once the Dutch gave him the last brushstroke.

As much as its name indicates otherwise, our protagonist is now more than 350 years old and has had time to live a few misfortunes. Nothing is known about his whereabouts until 1881 when a certain Arnoldus Andries des Tombe cast his eye on him at an auction in The Hague. As an art expert he immediately recognized the quality of the work, and he must have been the only one, since he took it for what today would be around 30 euros. An authentic bargain, come on. The lucky buyer did the work in Antwerp and kept it in his power throughout his life. When he died, in 1902, he bequeathed the painting to the Mauritshuis, where it can still be enjoyed today.

Girl with a Pearl Earring (44 × 39 cm) by Vermeer (ca. 1665) in a catalog photograph from 1924. Source: Image courtesy of the Mauritshuis.

During the twentieth century the work was subjected to a few cleaning treatments and many others varnished, among which include the restoration and conservation processes carried out in the sixties. The work was reinflated, previous retouches and varnishes were eliminated and a new colored varnish was applied. At this time we have to point out that, although today this last step would be unthinkable, the criteria of conservation and restoration have changed over time and at that time some considered that the yellow varnish dignified the work. In any case, and on the occasion of an exhibition dedicated to Vermeer, this varnish was removed in 1994.

This is the last restoration to which the piece has been subjected and in this process two interesting findings were made: the varnish had hidden the shine of the lips of the young woman and one of the gleams of the well-known pearl was not such. Specifically, what was thought to be a brush stroke of Vermeer to highlight the pearl was no more than a piece of paint that had accidentally turned around deceiving the experts for years. So the work lost a detail, but in return, it won another.

In the photograph on the right, the "false" glow discovered on the pearl is indicated.

What the eye does not see

As we have seen in previous entries, there are different techniques that allow us to explore details that at first glance we can not perceive. I'm talking about x-rays, infrared photography, ultraviolet fluorescence or low-level light. You can see how different the images are with some of these techniques.

X-ray (A), ultraviolet fluorescence photography (B) and low-light photography (C) (René Gerritsen). Source: Images provided by the Mauritshuis.

In the radiography (Image 3A) it can be seen that some areas are clearer. This is due to the presence of compounds with atoms that absorb more X-rays (just like our bones look white on a medical x-ray because of calcium). Thanks to this we can observe the nails of the frame or the areas painted with pigments that contain heavy atoms such as lead white (you will understand it better if you look at the eyes and the pearl). The radiography also allows us to better appreciate the fabric of the canvas, what the scientific team has used to calculate the number of linen yarns and compare the results with other Vermeer works.

Ultraviolet light (Image 3B) allows us to see the fluorescence of certain materials. You can see that all the work has some fluorescence and that is due to the varnish that covers it. Traditional varnishes, as they age, become fluorescent, which makes it possible to identify interventions after their application. For example, the dark spot on the eye corresponds to a retouch made in 1994. It is also worth mentioning the accentuated fluorescence on the lips, which indicates that Vermeer used some organic fluorescent lacquer to achieve this spectacular effect.

Finally, and although in this case no special technology is needed, the use of grazing light helps us to appreciate the three-dimensionality of the painting (Figure 3C). In this way, Vermeer's brushstroke and, above all, the cracks are appreciated, those cracks that have arisen over the years due to the aging of materials and the tensions caused by changes in environmental conditions.

The materials

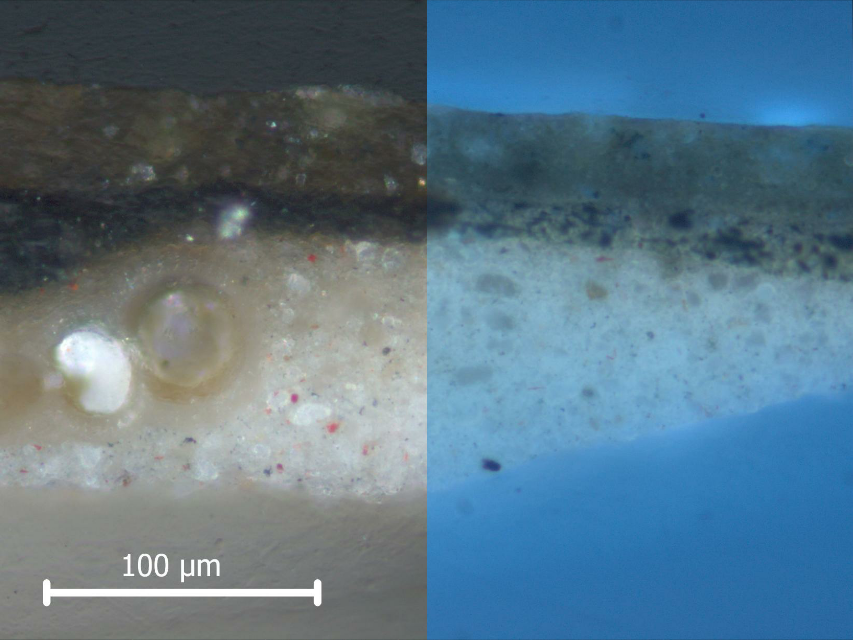

Vermeer may not have been a successful painter, but the fact of living in a city like Delft gave him access to top quality materials. Recall that the United Provinces were the commercial center par excellence of Europe, in addition to a reference in the manufacture of numerous products, including canvas. We have already mentioned that the artist used a linen canvas, but we have not said that this support is not suitable for direct painting and therefore it is necessary to cover it with a preparatory layer that offers a regular surface: the imprimatura. The imprint could be done by the painter himself, but at that time it was common to buy the prepared media. The stratigraphies of the work have allowed to quantify that the imprimatura of the young woman has a thickness of about 0.2 mm and is composed of lead white, ocher and chalk pigments. The chalk is a whitish rock of calcium carbonate and organic origin formed by fossils of certain algae. In fact, in Image 4 you can see some of these fossils "sleeping" under layers of paint.

Stratigraphy with the preparation and layers of paint (Rod Erdmann). On the left there are some cocolitos. The right half of the image corresponds to ultraviolet fluorescence photography and the left half to visible light photography. In this link you can see the interactive image. Source: Image courtesy of the Mauritshuis.

Another indispensable material in an oil is the oil used as a binder. The analysis of gas chromatography has confirmed that the oil used by Vermeer was flaxseed, the most common in this pictorial technique, and that it is obtained from the seeds of the same plant with which the canvas is made. These analyzes have also revealed that the artist used a previously treated oil to control drying, a critical factor when painting in oil. Interestingly, rapeseed oil has also been detected, but most likely its presence is due to contamination in the mill in which the oils were made. Logically, a section dedicated to artistic materials would not be complete without mentioning the pigments that, due to their relevance, will be treated in a differentiated section.

The pigments of Vermeer

We will start with one of the pigments that stands out in the composition, but that is not less important: red. A priori we only observe it on the lips which, as we have already said, are made with an organic lacquer. Analyzes using liquid chromatography have confirmed that it is carmine, a dye obtained from cochineal, which is also used in the food industry and, paradoxically, in cosmetic products such as lipstick. But this is not the only red of the oil.

Using X-ray fluorescence, a mapping was made of the presence of certain chemical elements, including mercury, and it was found to be very abundant in the lips and, to a lesser extent, in the skin (Image 5). The explanation is that Vermeer used cinnabar (HgS) among his red pigments. He probably painted the lips with this pigment and then covered it with red lacquer to obtain the desired effect. On the other hand, the presence of mercury on the girl's face (in which carmine has also been detected) is due to Vermeer adding this pigment to the paint to achieve the desired color to make the skin.

Mercury mapping obtained by X-ray fluorescence (detail). Source: Image courtesy of the Mauritshuis.

When talking about radiography we have mentioned a white pigment: the white lead (or white lead). This compound stands out, obviously, in all those parts of the painted portrait of that color: the blouse, the eyes, the pearl, etc. But if we turn our eyes to the X-ray of Image 2, we will see that there is one area of the face that is much whiter than the other. That means that in those areas Vermeer added more white pigment to his painting as a resource to achieve greater clarity. Thus, one of the culprits of the fabulous plays of light of the work is the white lead.

And from white to black. In this case the chemical analyzes have revealed the presence of two different pigments: carbon black and bone black. The first offers a more bluish tone and the second a brownish tone, hence Vermeer combined and mixed to achieve the desired tones. In any case, the black that attracts the most attention is that of the background itself. But, surprise! This area was not originally painted in that color. It is true that the Dutch applied a layer of black paint on the imprimatura, but on top it deposited a green glaze formed by two lacquers of vegetal origin: indigo (blue) and gualda (yellow). These lacquers are degraded under light exposure and are sensitive to other environmental factors, so that over time has made a dent in them and we have left a darker background than the one painted by Vermeer.

Let's leave the background aside and go back to the clothes of our protagonist. What color is the jacket you saw? Yellow? Brown? In fact there is no single answer, since Vermeer used different yellowish, reddish and brown pigments. The X-ray fluorescence has revealed that the clothes contain a large amount of iron, which indicates the presence of a family of pigments known as earths: yellow ocher (FeO (OH) · nH2O), red ocher (Fe2O3), siena, etc. These compounds are very common in nature and draw, in their own way, landscapes as spectacular as those of the French Roussillon.

And if we talk about clothes, we can not ignore the most striking garment: the turban. To the aforementioned yellow colors are here blue. A blue that is even more exotic than the turban to which it gives the color: ultramarine blue. We have already explained on another occasion that this pigment was brought from Afghanistan and that it was incredibly expensive. In The Young Woman of the Pearl, Vermeer not only uses it in the turban, but uses it mixed with other pigments (for example in the jacket). It is surprising that, without being a painter of the highest order in his time, he had access to such an exclusive product. But there are many things that we do not know about this genius who, in addition to this masterpiece, has given us jewelery such as View of Delft or The Milkmaid.

The signature

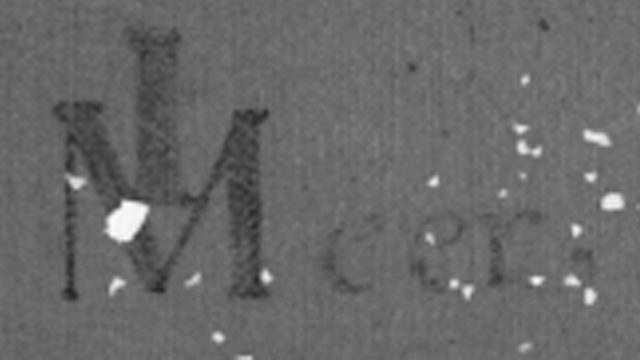

As if it were a painting, we will finish this article with the signature. Vermeer's, of course. Today it is a barely invisible trail in the upper left corner that merges with the gradient background. But, once again, X-ray fluorescence (in this case calcium) allows us to see more clearly, and thus distinguish the striking monogram left by the artist (Image 6). If you want to browse, here you can see the different signatures that he used throughout his career, which are almost as many as the works he painted.

The Vermeer monogram identified thanks to the calcium mapping with X-ray fluorescence (Annelies van Loon). Source: Image courtesy of the Mauritshuis.

N. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the Mauritshuis museum for providing access to the images obtained during the project The girl in the spotlight

To know more:

Girl with a blog by Abbie Vandivere

About the author: Oskar González is a professor at the Faculty of Science and Technology and at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the UPV / EHU.