“Andy Warhol: Genius or a Heartless Cynic Who Knew No Friends?”

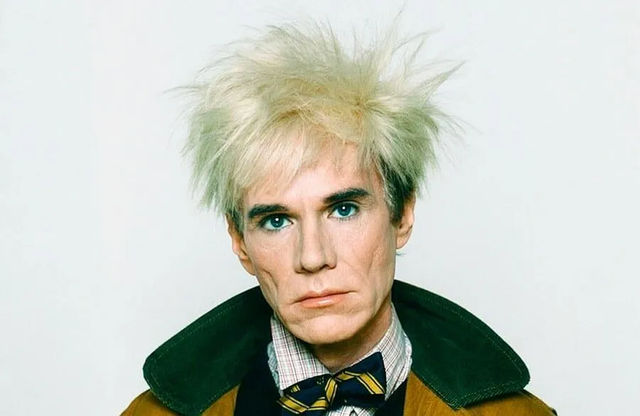

If he was called the king of pop art, was he also the king of life? Hardly. He did everything to secure his place in history. But what lies behind his immortal canvases? Today, we’ll dig deeper — into his demons, icy words, downfalls, deaths… And perhaps we’ll realize that this story holds neither brilliance nor inspiration, only emptiness and darkness.

Early Years and a Terrible Transformation

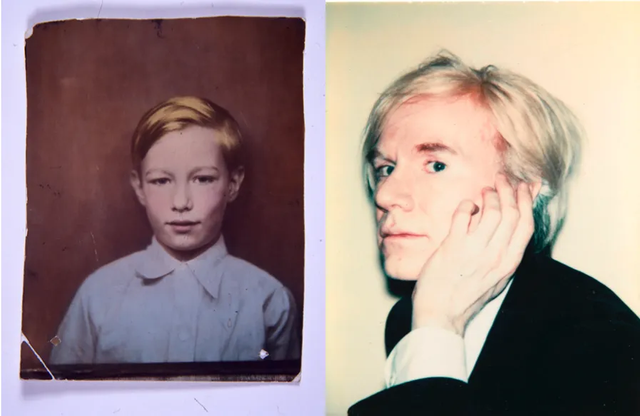

Andy Warhol was a weak, sickly boy. Born with a rare condition that left his skin covered in blotches — not the trendy kind of “autograph” from red-label designers, but a genuine nightmare for an 8-year-old kid. Imagine a face resembling a Picasso painting, not from genius but from illness. That was Warhol’s childhood in a nutshell — he seemed to be “made of something different.” And that material wasn’t particularly joyful.

But the illness wasn’t the worst part. No, the real horror was the branding. Not just at school, where Warhol became intimately acquainted with the practical meaning of “bullying.” Kids are cruel, especially when there’s an odd one out in the playground. His appearance became a perfect target for creative insults. Back then, the common wisdom was: “If you don’t look like us, you must be doing something wrong.”

His salvation? His mother. The one person who didn’t know the phrase “distance yourself from your child.” She supported him not because she foresaw his artistic genius but because, deep down, she understood what it was like to be “different.” She knew Andy wasn’t the kid destined to be a football star or prom king. He was more like the one who’d always side with the slightly unhinged geniuses of the world.

So, while his peers mocked him, his mother never promised him everything would be fine. Instead, she reminded him he was extraordinary. In her madness, she was right. Because when you grow up as a resident of the “other world,” you have two choices: break or create a new world where you rule.

This isolation and loneliness never let up. And honestly, who wants to hang out with people who only know how to laugh at you? Andy didn’t have “friends” growing up; he had art. Art was his only friend, his therapist. Maybe that solitude was what shaped him into what he became. Difficult? No, he just had no choice but to be himself. That was his superhero moment.

Now, onto New York. When Warhol finally made the move, everyone thought he was chasing inspiration. In reality, he was chasing fame and money. Because let’s face it, who else with a childhood like his moves to a city where the only way to survive is to either be famous or bankrupt?

New York was the perfect place where “paranoia” and “fame” were two sides of the same coin. Andy realized no one there would care about his blotchy skin. He knew that in a world where brands mattered more than feelings, survival meant good connections and a few wads of cash in your pocket.

He didn’t move to become an artist. He moved to become one of those “successful people” who hide behind perpetual smiles and clever quotes. Warhol didn’t want to be a hero; he wanted to be a brand. And judging by history, he nailed it.

Commerce, Cynicism, and the Rise of Pop Art

Andy Warhol earned his first paycheck sketching advertisements and packaging. Sounds like the most cliché success story ever, right? But if someone told you that the artist who became a symbol of revolution in art started his career designing ads for canned goods, you’d probably think it was a misunderstood cry of fashion.

Warhol didn’t overthink it. In a world where artists were considered near-deities, he was unapologetically a product. And, frankly, he couldn’t care less. Imagine being at a party where everyone is making money off their creativity, and you’re just standing there with a cup of coffee saying, “I’m just here for the money, guys. Don’t look for deeper meaning.” He didn’t want to be an intellectual because, let’s face it, intellectuals are always a headache. He wanted to be a commodity — something that sells, not someone lost among dusty books and rusty philosophical ideas.

Warhol once famously said, “Making money is art.” It wasn’t just a phrase — it was a manifesto. He wasn’t searching for meaning. Why bother when you can simply sell an idea that makes money? So here we are, sitting with our melancholic views on art, while Warhol strolled the streets of New York making bank by painting things everyone already bought. Warhol didn’t just sit at capitalism’s table; he reclined in its most comfortable chair.

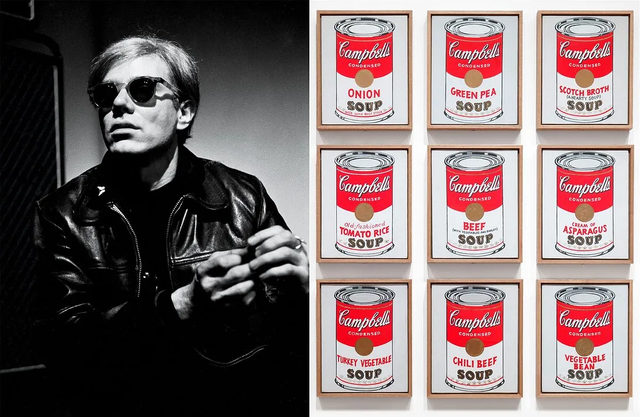

And then, as always, he went further. He turned a can of soup into art. Why? Because it was produced millions of times a day and existed in every home. Warhol realized it wasn’t just a can of food — it was the banal irony of existence. He transformed what everyone sees in their pantry into art. Who said “real art” had to be complex and understood by only a handful of people versed in “subjective reality”? That would’ve been too much work.

Warhol declared, “The best image is the one everybody sees every day.” It’s as if he decided to grab an ordinary soup can and say, “Hey, folks, you didn’t notice, but this is art.” And he didn’t care about the shockwaves it sent through the art world. For him, it was like drinking a glass of water — sip and move on. He was ready to destroy boundaries and shake foundations, but ultimately walk away with dollars in his pocket and a smug smile on his face.

And that’s his revolution. By tearing down the old, Warhol became — let’s be honest — the richest and most cynical artist of his time. Why bother seeking recognition from circles that don’t understand the game when you can be a god in a world ruled by money and meaningless phrases?

The Factory: An Eternal Carnival of Death and Manipulation

When Andy Warhol opened The Factory, it was more than just an art studio — it was his grimy kingdom, where chaos, cynicism, and darkness reigned supreme. He turned art into something far beyond painting — and, frankly, into something far filthier. The Factory drew everyone: eccentric celebrities, addicts, escapees from reality, and those desperately searching for some semblance of meaning in life. In short, it was a haven for people who viewed “stability” and “normality” as concepts from distant planets.

The Factory was like a free pass to an endless party, where everyone seemed to be chasing something they secretly hoped not to find. For Warhol, it was a circus of death and manipulation. Some came seeking inspiration, others fleeing their inner demons, but they all shared one thing: sooner or later, their lives veered disastrously off course. There were no rules at The Factory, just endless nights, screaming, drugs, and relentless attempts to escape the void.

One of Warhol’s “masterpieces” was Edie Sedgwick — an heiress, a child of privilege, too beautiful to be happy. Warhol saw in her everything that could serve as the perfect victim. She was his toy, his muse, his fragile figurine. He was almost like a director, forcing her to play the same role night after night, though the ending of her “show” was preordained. Edie would do anything for him: die in front of the audience, destroy herself for arthouse films, dance to the acid rhythms of her crumbling psyche. But Warhol didn’t care about saving her — he wasn’t her friend or her lover. He was a spectator in the front row, calmly watching as one mask after another slipped from her face.

And when her life spiraled into oblivion, he merely shrugged. She died of an overdose, leaving behind photos where her eyes already seemed to know what hell looked like. Warhol’s reaction? Nothing. “Death is the most boring thing that can happen,” he once said. His philosophy of cynicism and cold calculation was chilling in its bluntness.

But The Factory saw more than Edie. Countless others left broken, shattered like faded memories. Addicts, writers, musicians — many of them, lost in a narcotic haze, tried to find themselves but only stumbled into emptiness. Warhol surrounded himself with people he called “muses,” but they were more like his living puppets, loyal to their king and willing to die for him. And he, with his ever-cold stare, seemed to relish the spectacle — a show where applause marked the end.

The Factory wasn’t just a workshop — it was a carnival of self-destruction, where human lives were spent like tickets to a performance. No one left unscathed. But who cared? In the end, Andy just shrugged. As long as his empire of chaos thrived, regret was unnecessary.

Valerie Solanas’ Assassination Attempt: Long-Awaited Retribution

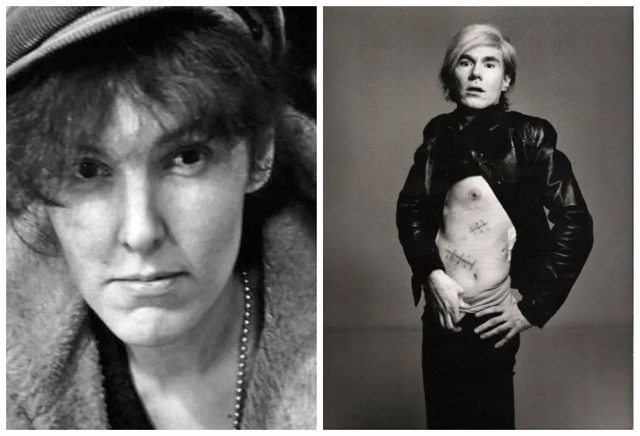

Valerie Solanas’ story is an ode to destruction that begins with quiet rage and ends with the thunder of gunshots. A feminist, writer, and revolutionary with a touch of madness, she wasn’t content to play a part in Warhol’s spectacle. She decided to tear it down completely. In this tragedy, Warhol, as always, underestimated his muse.

Valerie wasn’t one of those who merely dreamed of brushing against fame or landing a minor role in Warhol’s arthouse films. She approached him with her manifesto and a handwritten script — her script, mind you. She wasn’t after success or glory; she sought a serious conversation. But Warhol, true to form, saw nothing more than another “weird girl” among the crowd that flocked to him daily. He didn’t even bother to read her script — a fatal mistake.

Her patience snapped. And when Warhol saw Valerie pull out a gun, he likely thought it was yet another performance — until the bullets started flying. Three shots. He couldn’t believe that such a small, deranged woman was capable of such a grand act of violence. Ironically, the master of manipulation was brought down by one of his own victims. If he could have, he might have dismissed it as a pathetic drama. And in a way, it was — a drama in his signature style, cynical and with a brutal ending.

He was barely saved. Doctors fought for his life, leaving him with a collection of scars and trauma — a permanent reminder that even muses can rebel. Yet what hurt him more than the physical injuries was the humiliation. Warhol, the emperor of art, had nearly been killed by a “crazy fan.” He would later say, “If people weren’t so pathetic, they wouldn’t shoot me.” Of course, he never saw his own role in the event. In his eyes, it was her act of madness — but perhaps it was also her way of reminding him that even art has its limits.

After the attack, Warhol retreated further into his shell, surrounding himself with people but maintaining a cold detachment that ultimately turned him into a lifeless statue. He continued creating “art” fueled by detachment and cynicism, filling the walls of his studio with new projects. But perhaps deep down, he always anticipated that another one of his muses might return with a gun.

Valerie Solanas’ story later inspired a film where her madness was portrayed not as a diagnosis but as an act of desperate retribution. It’s as if all her attempts to reach him froze in that singular, explosive moment.

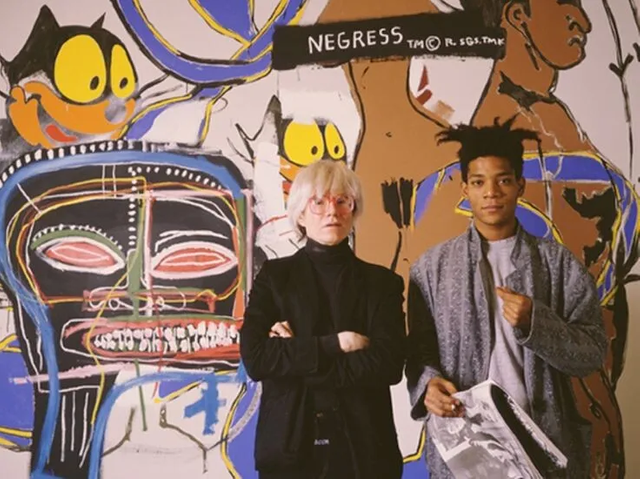

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Union of Genius and Cynic

Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat formed a partnership that seemed to be designed by absurdity itself. Their relationship could be called a romance — if romantic relationships ever resembled a cold shower with a live wire. Warhol, a man who spent his life hiding behind thick glasses and a cynical smile, and Basquiat, a vibrant, untamed street genius for whom creativity was a scream, became a duo, but they were more like a chemical reaction destined to explode in their faces.

Imagine New York in the 1980s: Basquiat appears on the scene like a comet from the streets, cigarette in hand, burning with a stubborn thirst for life, while Warhol, the “king” of pop art, decides that young blood might look good in his commercial glass. Andy sees in Jean-Michel not a person, but a new brand, a “muse for the galleries” that could be wrapped up and sold. And Basquiat, perhaps, wasn’t opposed to that. In the beginning, it almost seemed harmonious: Basquiat’s fury on canvas collided with Warhol’s cold, mechanical precision. The works appeared as a clash of elements: one alive, the other mechanical, one shouting, the other silently detached.

Critics, of course, screamed with delight, but for Basquiat, it was a deal with the devil. In essence, he became a decoration for Warhol’s myth, a souvenir from Andy’s shop. While working with him, Jean-Michel didn’t feel like a genius, but a commodity. Perhaps deep down, Warhol despised him, but he was enchanted by his audacity. And Basquiat loved him and couldn’t understand why it hurt. It was a love mixed with pain and manipulation — a union that, like all good things, was destined to end in catastrophe.

When Warhol suddenly died, Basquiat realized that he had lost both a friend and a tormentor, a person with whom they mutually hated each other, yet couldn’t exist apart. In the film “Basquiat”, the moment of his devastation is portrayed, but the true pain ran much deeper. Without Warhol, the world became unbearable to him. He returned to drugs, and soon after, he too was gone — as if they both shared a tragic balance.

In the end, their legacy became a museum of pain and solitude, a love that was a distorted mirror. Warhol often repeated, “Death is the most boring thing that can happen,” as though he couldn’t quite believe that one day he too would die. And Basquiat, perhaps, was the only one who truly understood him: two outsiders who hoped that pain could be erased by fame.

Late Works and Obsession with Death

In his later years, Warhol stopped focusing solely on soup — he became captivated by skulls, catastrophes, and electric chairs. Death became his new muse, his companion, with whom he spent long nights contemplating how best to sell it. He showcased it as the finest commodity, as if offering the audience a glimpse of “how luxuriously one can leave without feeling anything.” Paranoia engulfed him, but at the same time, it seemed to become his personal brand. “I live like a machine, I die like a machine,” he would say, as if he were just another product in his own store. In art, everything must serve a purpose — even his own fear.

Andy didn’t turn himself into a cold machine by accident. Perhaps he was trying to distance himself from his own fear, from that emptiness inside him that threatened to consume him entirely. Death, for him, wasn’t just a terrifying shadow; it became the one thing he tried to control, like a bank account. His last paintings — electric chairs, skulls — were his message to the world: even death could be turned into an object for which you would be charged in dollars.

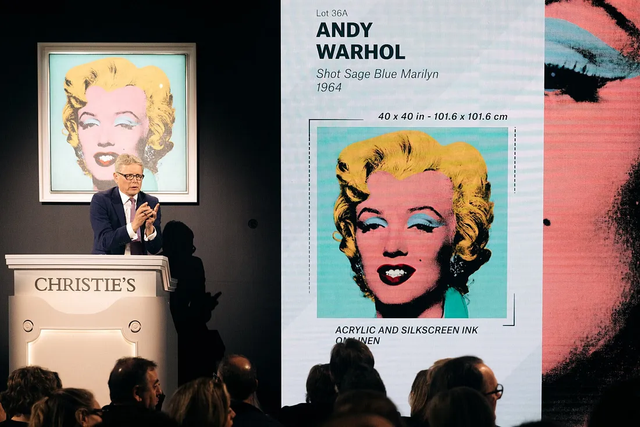

The Legacy of Andy Warhol — The Cost of Fame and the Tragedy of Legacy

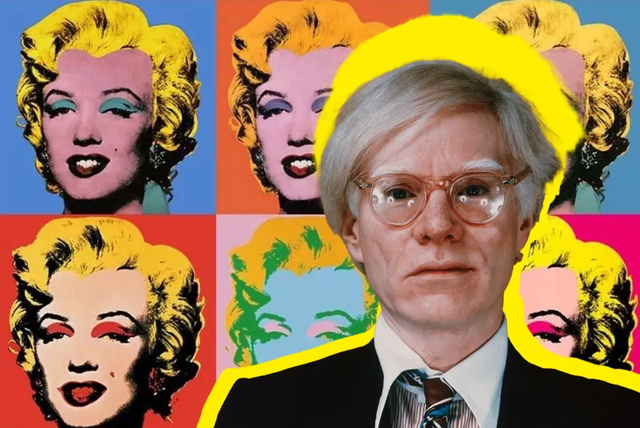

When Andy died, he left his commercial genius to the Andy Warhol Foundation — with one goal in mind: to support contemporary art, which he himself never truly became. The foundation, much like his art, is a money-making machine. The “workouts” he tossed around like cans of soup have transformed into icons of art, just look at his “Marilyn.” In 2022, it sold at auction for $195 million, almost confirming the notion that price can justify any fantasy.

At the ironic peak, his paintings became the embodiment of capitalist success. Warhol saw art as a product, and, as with all genius, this turned out to be absolutely true. The meaning of his legacy is as simple as a dollar: art can be bought. And sold. And, with some effort, rewrapped and sold again. Warhol didn’t leave the art world — he left it a price tag.

Shocking Philosophy and Immortality Through Heartlessness

So who was he — an idol, a villain, the god of marketing, a pragmatic philosopher? A person who turned art toward the world of commerce, taking all its soul with him? In the end, Andy Warhol remained surrounded by random people, utterly alone. Looking at his works, at the artificial neon glow instead of sincerity, you understand that behind this coldness lies emptiness.

He proved that death could be put on display. His words, “Death is the most boring thing that can happen,” became his slogan. Perhaps geniuses look exactly like this — like emptiness, where nothing remains. Or maybe genius is just the deceased who hasn’t yet realized they’re gone.

Devil or Genius?

“Andy Warhol is the symbol of cold calculation, success without meaning, art with no emotion. He was the mirror of our darkness, our desire to look at death without seeing it. And he knew it would consume us. In his world, fame was the only form of immortality, and he disdainfully gave it to us.

Thus, looking at Andy Warhol, each person decides for themselves what kind of man he was. A devil? Or, after all, a genius? Perhaps the answers will remain behind that wall, behind which he hid his emptiness.”

Has this story inspired you? Write in the comments and subscribe to discuss important topics together! 💬

Manual Curation of "Seven Network Project".

#artonsteemit

ᴀʀᴛ & ᴀʀᴛɪꜱᴛꜱ

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit