Last Tuesday, the Supreme Court of India declined to endorse same-sex marriages, causing dismay to numerous LGBTQ+ activists and couples. Historians note that such relationships were not uncommon in India many centuries ago.

During her time at Delhi University, from the 1970s to 1996, Ruth Vanita, an activist and author, noticed that discussions on same-sex love were virtually absent in academic circles. Concurrently, while involved in the women's movement, she observed a similar absence of conversation on the subject, whether among left-wing or right-wing feminists.

In her 2004 essay, Prof. Vanita mentioned that many prominent women's rights activists identified as lesbians. However, this identity was seldom spoken about within activist circles. By 2018, a significant shift occurred when the Indian Supreme Court decriminalized gay relations, revoking a previous 2013 verdict that maintained a British colonial-era law, section 377, which deemed such relationships "unnatural."

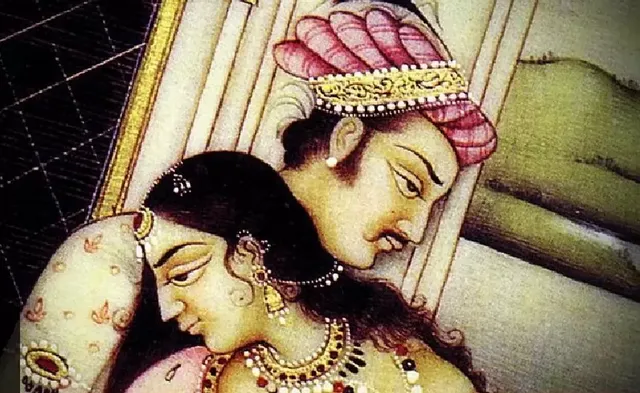

Some in India were apprehensive that removing the old law was pushing the country towards adopting Western liberal values. However, in Prof. Vanita's perspective, India's history proves otherwise. Together with historian Saleem Kidwai, she compiled and analyzed various texts from 15 Indian languages for the collection "Same-Sex Love in India: Readings from Literature and History." Their research revealed that same-sex love was prevalent and generally accepted in ancient and medieval India.

Historian Rana Safvi affirmed this, referencing depictions of homosexual relationships in historical sites like the Khajuraho temples and Mughal accounts. This view was also shared by the Supreme Court judges, with Chief Justice DY Chandrachud remarking on the long-standing acceptance of queerness in India.

Prof. Vanita believes that British colonization brought about a drastic change in India's views on sexuality and love, as Victorian ideals began to overshadow indigenous traditions. The Kamasutra, an ancient Indian text on eroticism, acknowledges same-sex relationships. Prof. Vanita also found evidence of ancient beliefs in reincarnation, suggesting that same-sex bonds could span multiple lifetimes.

A landmark event in modern India was in 1988 when two policewomen in Madhya Pradesh, Leela Namdeo and Urmila Srivastava, held a wedding ceremony. Although they faced professional consequences, their community was largely supportive.

Over the years, media reported on several such ceremonies, particularly involving young Hindu women from smaller towns. Despite not having affiliations with advocacy groups, these weddings, albeit not legally binding, represent a societal shift.

Unfortunately, societal pressures have led some same-sex couples to end their lives. Prof. Vanita recalls countless young couples, predominantly women, who took such tragic steps due to societal rejection.

On the same Tuesday, the Supreme Court entrusted the decision of legalizing same-sex marriage to the parliament, proposing a committee to explore rights for LGBTQ+ couples. Prof. Vanita expressed her disappointment but acknowledged the divisive public opinion.

Currently, 34 countries recognize same-sex marriages. India's journey toward joining them depends on political and societal shifts. Implementing anti-discrimination regulations would be a positive first step.