Summary

- Australia's growth rate is less than 3% per annum and its interest rates is 1.5%

- Australia looks more like it may suffer from deflation due to the economic success of developing and third world countries such as China. This allows for Australians to seek cheaper alternatives.

- Inflation is currently close or surpassing wage growth

- Property prices and household median income ratio is at 12 for Sydney, 10 for Melbourne and six for other capital cities

- Interest rate loans are ~5% and household debt is currently ~190%, with ~33% of borrowers having less than a month buffer emergency funds

- Immigration may be putting upwards pressure on housing prices and infrastructure demands. Infrastructure spending has been increased by $71billion federally.

- A savings account may no longer be seen as a good form of investment, and may be losing people money due to the interest being lower than inflation.

- Consumer confidence is wavering.

Introduction

Australia has currently experienced a growth rate of less than 3% per annum since 2013. Interest rates are at an all-time low of 1.5% and are expected to lower within the next few months. At a time where consumer confidence is staggering, investors are wondering what is happening to Australia, and where it will most likely to lead. This blog will be looking at the current situation on interest rates in Australia and the factors affecting Australia's economic growth.

The current situation on interest rates in Australia

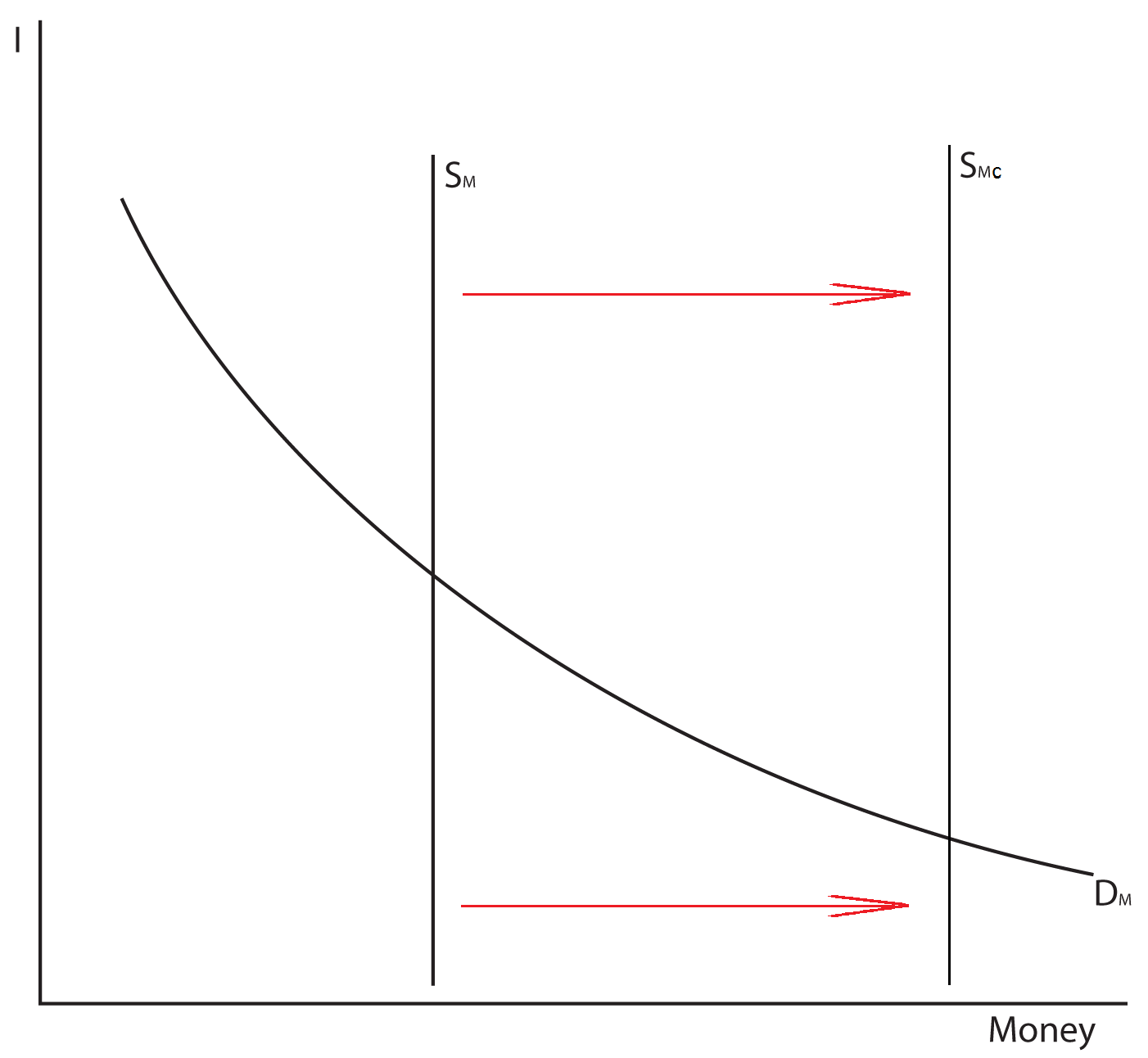

The RBA began to reduce interest rates after the Global Financial Crisis to stimulate the economy and to entice people people to borrow. However, interest rates have reduced from 7.25% in August of 2008 to 1.5% in July 2017. Figure 3, shows, theoretically, how interest rates have moved the position of the supply curve of money from Sm to Smc.

The RBA has given many reason for its reduction of interest rates, primarily to support domestic demand and due to lower than expected inflation figures.

However, as the interest rate in Australia decrease, the demand for the AUD decreases. This means, to get the currency value of a product, sellers will have to increase their prices so they can sell their good for the value they wish to sell it for.

This has been happening in the developed world, and is not contained to Australia. Where countries have lowered their interest rates to artificially low levels to stimulate economic growth; US’s is 1.25%, EU’s is 0%, New Zealand’s is 1.75%, UK’s is 0.25% and Japan’s is 0%.

It should be noted that developing countries, especially those associated with BRICKS, still have reasonably high interest rates. Russia’s is 9%, China’s is 4.35%, Brazil’s is 10%, RSA’s is 7% and India’s is 6.25%.

What is meant to occur from this position is some form of hyperinflation. Whereby the money starts becoming worthless and untrusted. When this happens, the RBA will raise interest rates to combat this hyperinflation. Hyperinflation will come about due to lost trust of the AUD of investors and those that use it. However, it does not seem like this is happening, and this is a problem. Evidence from the RBA shows in most cases, deflation is occurring.

It should be noted inflationary pressure may continue to decrease, as there is more and more demand for investing into developed countries from developing and third world countries. However, during a recession or downturn, it may be best to increase interest rates to allow for saving to become a proper form of investment.

Factors affecting Australia's economic growth

Below is a list and brief description of factors that are affecting the Australian economic growth.

Wage growth

- A consumer on an hourly wage is losing real income at the current rate (i.e. their ability to purchase items is becoming more limited).

- Inflation has surpassed wage growth by the end of Q1 2017. The ABS reported hourly wage growth has grown by 1.9% from Q4 2016 to Q1 2017, but inflation has grown on average by 1.8% (1.5%+2.1%/2) From Q4 2016 to Q1 2017. However, they are reporting a 2.1% inflation rise in Q1 2017 from December 2016 to March 2017.

- Since people’s salaries are not getting higher, people's buying power is reducing. Therefore, more and more goods and services are becoming more out of reach of more and more consumers.

- Retailers are moving more employees from part-time or full-time positions to casual positions, due to the lower amount of money retailers have to pay their employees. This has caused a lot of people to be underemployed, working positions or jobs when they would like to work more hours to receive more income and skills.

Property

- In 1980, the ratio between property prices and household median income was around three (excluding Sydney) nationwide. In 2017, that ratio has increased to around four in 1996, to above 12 for Sydney, around 10 for Melbourne and around six for other capitals nationally.

- Property prices have inflated due to cheaper loans and the introduction of foreign buyers, noticeably China, purchasing property for either lifestyle or investment purposes. The fact they have a lot of money and are willing to pay the prices on offer will drive up property prices.

- Since wage growth is below inflation, property will be more out of reach for consumers, especially those with casual jobs.

- This housing bubble is also occurring around the world. Demographia published a survey, using data from the 3rd quarter 2016, showing different ratios between property prices and household median income overseas. San Francisco’s was 9.2, Auckland’s was 10.0, Vancouver’s was 11.8 and Hong Kong’s was possibly an outlier at 18.1.

Asset bubbles

- Asset bubbles occur when so much money has been put into a single form of asset that the prices over increase their true value.

- Alan Kohler from The Australian remarked negative gearing is also contributing to inflating the housing prices.

- Negative gearing is where if the loan repayments on a housing loan are higher than the rent received on the house purchase, you can claim the difference as a tax deduction. Negative gearing can also be used for share purchases, which means there may be a chance that share prices are also in an asset bubble.

Foreign Activity

- China is putting downwards pressure on Australian products. China does this through cheap labor and production costs that allow for them to undercut the market.

- China’s ability to decrease their costs of production is the chief driver of deflation that are experienced at artificial low interest rates.

- One item to note. The IMP reported China’s credit-to-GDP ratio is currently “high”. On current trends, the ratio is said debt is expected to hit 210% of GDP.

- The amount of agricultural land owned by foreigners in Australia, reported by the Australian Tax Office, stands at 13.6% for the year ending June 2016. There are no other past statistics due to the tax office first starting data collection of foreign ownership in 2015.

Low interest rate loans

- Interest rate for a household loan currently stands at around 5% per annum compounded yearly.

- Low interest rate loans encourage debt, allow for a once in a decade time to get cheap capital or to buy a house cheaply with a similar mortgage repayment. However, it that capital is to be sold off again, it will be hard to sell it once interest rates rise.

Debt

- Even though repayments of loans have become more affordable, household debt has exploded. The RBA reported house debt to income has increased from ~70% in January 1990 to ~190% from around June 2017.

- ~33% of borrowers have less than a month buffer. Depending on how tight interest rates get if increased, they may sell on mass. This quick high-volume sell will cause a crash.

Immigration

- Increases in immigration have allowed for a greater pool of labor, productiveness, and citizens that can be taxed. However, immigration will increase the demand on infrastructure and increase housing prices.

- The Australian governments federally and state wide are attempting to deal with this by allocating funds for new railway lines and a new Sydney airport. State governments are also allocating funds to improve existing infrastructure; improving railways, roads et cetera. The costs for these projects run into the billions. For example, the federal budget's infrastructure spending for 2017 is $71 billion.

- Note. With the increases on the standards of living, more Australians will start speaking out of they feel the status quo is unfair to them. If this gets worse enough, often foreigners are the ones who are targeted first when this reaches a high enough peak (eg. Xenophobic attacks on entrepreneurs in South Africa).

Viable Alternatives

- National Australia Bank (NAB) found retail-consumer spending had a very slowly increased around 0.8% on average in the first three months of 2017, but online retail increased by 13.5% for the year ending June 2016. Consumers may be finding alternatives to expensive products, or cutting back on them. Most products and services excluding supermarkets have generally been increasing in price, and consumers may be looking for alternatives.

- These alternatives do not need to increase their prices, as they are undercutting their competition and gaining market share.

Savings

- The maximum savings variable rate of accounts in Australia is between 1.8% and 3.05% (from finder.com.au and infochoice.com.au). the ABS reported inflation was at 2.1% in Q1 2017. This means some people will be losing savings, and some will be getting almost nothing from their investment in a bank account.

- To many there may be no point in saving a huge quantity of money in a bank account if it has a small or no potential to grow overtime.

- As a result, savers may turn to riskier assets, such as shares and property, to grow and protect their savings.

- Given the amount of money banks are giving out in loans, banks are effectively using a lot of savers money to conduct business.

Consumer confidence

- ANZ-Roy Morgans reported a 2.4% bounce in consumer confidence since the Federal government budget release on the 9th of May. However, Westpac recorded a continuous drop of consumer confidence from 99.7 to 96.23 from March to June 2017.

- These two different sets require more accurate details on where specifically consumer confidence is at. It is always best to take the worst-case scenario than the best.

- Therefore, consumer confidence is not as strong as it necessarily should be.

- This may be a sign of lack of confidence amongst consumers, particularly buyers in the property sector. If consumer’s confidence is not as high as it should be, as shown from the data, then you will see a slowdown of the market. There may be people who are able to pay for a house. However, these people deliberately withhold purchasing houses on the market, and wait for prices to decrease.

Conclusion

Australia currently has one of the largest housing bubbles in the world. Coupled with increasing demand on the standard of living and Australia could be in for a rough time in the next ten years. Social upheaval seems to be slowly increasing in Australia as well, as a result of the above. More of Australia’s population will start speaking out of they feel the status quo is unfair to them.

Sources

Arif, M, Plank, D 2017, ‘ANZ-ROY MARGAN AUSTRLIAN CONSUMER CONFIDENCE MEDIA RELEASE’, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group, retrieved 9 July 2017, http://www.media.anz.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=248677&p=irol-roymorgan.

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017, ‘Wage Price Index, Australia, March 2017’, Australia Bureau of Statistics, retrieved 9 July 2017, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/6345.0.

Australian Tax Office 2016, ‘Register of Foreign Ownership of Agricultural Land’, Australian Government, retrieved 10 July 2017, https://firb.gov.au/files/2016/08/Register_of_foreign_ownership_of_agricultural_land.pdf.

Finder.com.au n.d., ‘Savings Account Comparison’, finder.com.au, retrieved 9 July 2017, https://www.finder.com.au/savings-accounts/best-savings-accounts.

global-rates.com, ‘Central banks – summary of current interest rates’, global-rates.com, retrieved 9 July 2017, http://www.global-rates.com/interest-rates/central-banks/central-banks.aspx.

Hartwich, O 2016, ‘13th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2017’, Demographia, retrieved 8 July 2017, http://www.demographia.com/dhi.pdf.

Indivigloi, D 2011, ‘5 Problems With Ultra-Low Interest Rates’, The Atlantic, retrieved 8 July 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2011/04/5-problems-with-ultra-low-interest-rates/237038/.

Infochoice.com.au n.d., ‘Saving Accounts’, infochoice.com.au, retrieved 9 July 2017, http://www.infochoice.com.au/banking/savings-account/online-savings/.

Kohler, A 2017, ‘Time to admit failed doctrine on low interest rates’, The Australian, retrieved 8 July 2017, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/opinion/alan-kohler/time-to-admit-failed-doctrine-on-low-interest-rates/news-story/cae6d68e27f94663244b1eab5fd09885.

Lowe, P 2013 – 2016, ‘Monetary Policy Decision’, Reserve Bank of Australia, retrieved 8 June 2017, https://www.rba.gov.au/monetary-policy/int-rate-decisions/2016/.

Maliszewski, W et al. 2016, ‘IMF Working Paper: Resolving China’s Corporate Debt Problem’, International Monetary Fund, pp. 22, retrieved 12 July 2017, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16203.pdf.

NAB Group Economics 2016, 'NAB Online Retail Sales Index: In-depth report - June 2016', NAB retrieved 8 June 2017, http://business.nab.com.au/nab-online-retail-sales-index-june-2016-17897/.

Reserve bank of Australia 2017, ‘Measurement of Consumer Price Inflation’, Reserve Bank of Australia, retrieved 9 July 2017, http://www.rba.gov.au/inflation/measures-cpi.html.

Reserve bank of Australia 2017, ‘Interest Rate and Yields – Money Market – Daily – 1995 to 17 May 2013 – F2’, Reserve Bank of Australia, retrieved 12 July 2017, http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/historical-data.html.

Reserve Bank of Australia 2017, The Australian Economy and Financial Markets’, Reserve Bank of Australia, pp. 6, retrieved 12 July 2017, http://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/pdf/chart-pack.pdf?v=2017-07-12-03-39-51.

Solan, J 2017, ‘Housing affordability: low interest rates push up property prices’, The Australia, retrieved 8 July 2017, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/columnists/judith-sloan/housing-affordability-low-interest-rates-push-up-property-prices/news-story/3ed1892a1e11c1aa6e85cb4ce51d0dc9.

Stevens, G 2013 – 2016, ‘Monetary Policy Decision’, Reserve Bank fo Australia, retrieved 8 June 2017, https://www.rba.gov.au/monetary-policy/int-rate-decisions/2013/.