in Bancambios, Latin America and Africa are the markets we are most passionate about.

Millions of people across the African continent still don’t have access to banking services. They are being denied the opportunity for full and sustainable economic participation. Consequently, their prosperity, and that of their communities is being held back. Closing the unbanked gap is not simple and straightforward, but it is vitally important, writes Promoth Manghat. On 4 September 2019, he will be speaking at the World Economic Forum on Africa, and participating in a panel event entitled Advancing financial inclusion across Africa.

Most of us are familiar with the routine of leaving home to go to work in the morning. We do so in the expectation of returning to our families and loved ones later that day. But for the 178 million migrant workers around the world, the picture looks a little different.

A significant number of them have left behind the familiarity of their home country to seek out opportunity in a foreign land. They work hard and do whatever they can to improve their prospects, sending money to the ones they left behind.

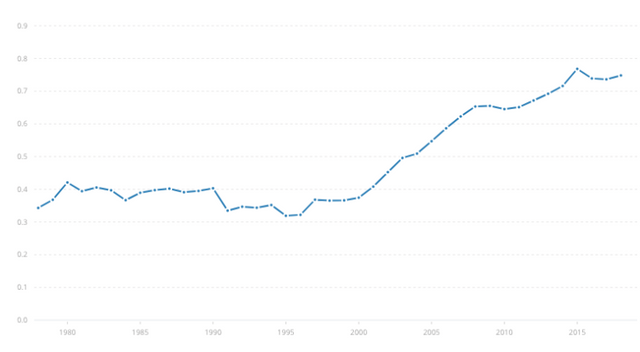

According to the World Bank, the value of global remittances was $689 billion in 2018. That’s up from $633 billion in 2017. A record high of $529 billion that was sent to low- and middle-income countries – an increase of almost 10% on the previous year.

1978-2018 Global remittance growth as a percentage of GDP (World Bank)

The chief beneficiaries of those remittances were India ($79 billion), China ($67 billion), Mexico ($36 billion), the Philippines ($34 billion), and Egypt ($29 billion). And for some nations, those remittances are extremely important; in 2018, 40% of Tonga’s GDP was made up of the remittances sent by the country’s migrant workforce, for example.

Not all heroes wear capes – some of them work hard thousands of miles from home, for little pay and even less personal fulfilment, all to support their family.

The 10 countries where remittances make up the largest percentage of GDP (World Bank)

Money is a means to an end – not the end itself

When that money reaches the folks back home it can unlock life-changing opportunities for individuals, kickstart economic activity for communities, and even ignite sustainable economic growth at the national level.

But only if it can be put to work quickly and easily so that it can reach its full economic potential.

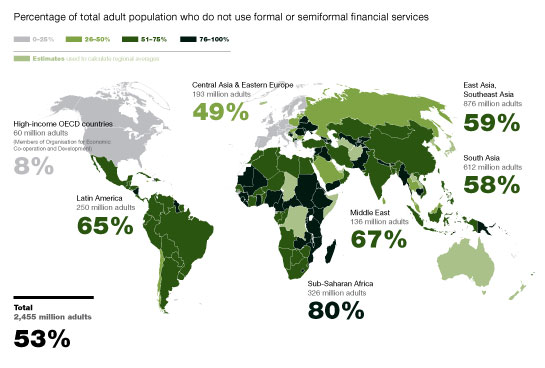

As things stand, there is one major barrier preventing that from happening. According to World Bank data, something like two-thirds of people across the great African continent are unbanked.

That’s an astonishing statistic.

Around 95 million of these unbanked adults receive cash payments for agricultural products and roughly 65 million save using semi-formal methods. And some even turn to practices such as hoarding cash and burying it. For someone unfamiliar with banking services, or maybe a little distrustful of them, such activities can provide a sense of control and reassurance.

But burying money is not safe or secure, and while it’s lying on the ground it’s not part of the wider economic ecosystem.

The question facing all of us in the banking, finance and fintech world is, how do we tackle the problem of the unbanked in Africa and help unlock greater economic and financial firepower across this exciting and vibrant region? And there’s an additional dimension to consider – how do we do that in a manner that will appeal to those we are offering new services to?

The percentage of people not using formal or semi-formal banking services (McKinsey)

Culture vs technology

Technology is an important part of closing the unbanked gap. But this is not solely a technology problem. The African continent is vast, and in many places, population density is low, as people are spread out across large and sometimes remote areas.

A chronic lack of physical infrastructure over many decades has created some fundamental challenges. There aren’t always roads where they are needed, thanks to flooding or landslides and so on. There might not even be a reliable supply of energy for a mobile phone network to keep its base stations and towers in constant operation.

There are also cultural differences and habits to keep in mind. In countries where there isn’t a well-developed, mass-market banking sector, there is an opportunity for technology to short-circuit traditional financial services evolution. Others though have long-standing patterns of behavior that simply won’t shift overnight.

In the US, people have been paying with plastic for decades. The cards they already carry offer most of the benefits of a mobile wallet – ease, security, and convenience. In Germany and India, cash is still everyone’s favorite way to pay for things. Attempts to wean people off it haven’t always gone well – so manage your expectations.

Meanwhile, in Kenya, financial inclusion stands at 82%, thanks in no small part to the mobile wallet M-Pesa. It handled over 1.7 billion transactions between 2016 and 2017, and around 93% of Kenyans have access to mobile payments.

On the other side of the continent, fewer than 6% of Nigerians use their mobile phones for banking. Not necessarily because they distrust technology. It is more likely to be related to the decision of the Nigerian regulator to block mobile network operators from obtaining the licenses needed to offer payment transfers.

Defining a three-step plan

If this tells us anything, it’s that one size does not fit all – failing to adapt to the needs of local markets is unlikely to end well. Despite this, there are still some commonalities that ought to be the foundation of a strategy to close the unbanked gap in Africa.

Focus on the last mile

Two things are important here: access to services and the cost of using them. From mobile money to a network of kiosks in existing retail locations, you have to be where your customers are. And you have to price things in a considerate manner. The average cost of sending remittances into Africa is around 9%. In some countries (Liberia and Gambia) it is as high as 20%. That’s a large slice of the benefit that could be going to the recipient.An ecosystem of latent connections

Remittances can be a gateway to enhanced financial inclusion. But to start offering loans or savings products to people, financial services companies need to be able to exchange data, access credit reports and so on. The more reasons you give someone to use mobile money solutions, the greater the ripple effect of their transactions is likely to become.Share and share alike

The sharing economy is built on networks of trust. If there’s one thing you are likely to find in abundance in many African communities, it is deep bonds of trust. So the sharing economy in Africa could be one of the world’s greatest success stories. By 2050, it’s estimated that the youth population will have increased by 50% and Africa will have the largest number of young people on the planet. And their appetite for a sharing economy is unlikely to diminish.

We are all part of something bigger

Spare a thought for the millions of people who leave everything behind in pursuit of opportunity and advancement. It can be a long and lonely road to travel, both literally and figuratively.

But no man is an island, as the poet John Donne famously wrote – we are all connected to and influenced by one another. For those migrant workers, their connections to family, friends and loved ones is an emotional lifeline. To help grow financial inclusion across Africa, we will all need to adopt a similar connected outlook.

We can start by encouraging collaborations and partnerships that enable public-private investments in infrastructure. We need to address and respect different cultural perspectives and ensure we can meet people’s needs in a way that puts the customer first.

And we must always keep in mind that closing the unbanked gap is a mechanism for ongoing, sustainable prosperity for some of the communities who need it most.

Advancing financial inclusion across Africa is more important than ever – here’s why

September 2, 2019 By Promoth Manghat, Group CEO, Finablr