Historical Setting- (iii).

Two Nations Concept, 1930-47.

The political tumult in India amid the late 1920s and the 1930s delivered the principal explanations of a different state as an outflow of Muslim cognizance. Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1873-1938), an Islamic evangelist writer and scholar, talked about contemporary issues in his presidential deliver to the Muslim League gathering at Allahabad in 1930. He considered India to be Asia in little, in which a unitary type of government was incomprehensible and network instead of an area waAs the reason for distinguishing proof. To Iqbal, communalism in its most astounding sense was the way to the development of an amicable entire in India. In this way, he requested the making of a confederated India that would incorporate a Muslim state comprising of Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind, and Baluchistan. In consequent talks and compositions, Iqbal emphasized the cases of Muslims to be viewed as a country "in light of solidarity of dialect, race, history, religion, and character of monetary interests.''

Iqbal gave no name to his anticipated express; that was finished by Chaudhari Rahmat Mi and a gathering of understudies at Cambridge University who issued a flyer in 1933 entitled "Now or Never." They restricted the possibility of alliance, denied that India was a solitary nation, and requested segment into locales, the northwest getting national status as "Pakistan." They made up the name Pakistan by taking the P from Punjab, A from Afghania (Rahmat's name for North-West Frontier Province), K from Kashmir, S from Sind, and Tan from Baluchistan. (At the point when written in Urdu, the word Pakistan has no letter I between the k and the s.) The name signifies "the place that is known for the Paks, the profoundly unadulterated and clean." There was a multiplication of articles on the topic of Pakistan communicating the subjective conviction of nationhood, however there was no coordination of political push to accomplish it. There was no reference to Bengal.

In 1934 Mohammad AliJinnah (1876-1948) assumed control over the administration of the Muslim League, which was without a feeling of mission and unfit to supplant the Khalifat Movement, which had joined religion, patriotism, and political enterprise. Jinnah start reestablishing a feeling of reason to Muslims. He stressed the "Two Nations" hypothesis in view of the clashing thoughts and originations of Hinduism and Islam.

By the late 1930s, Jinnah was persuaded of the requirement for a binding together issue among Muslims, and the proposed province of Pakistan was the undeniable answer. In its tradition on March 23, 1940, in Lahore, the Muslim League settled that the territories of Muslim larger part in the northwest and the upper east of India ought to be gathered in "constituent states to be independent and sovereign" and that no autonomy design without this arrangement would be satisfactory to the Muslims. Organization was rejected and, however confederation on regular interests with whatever is left of India was visualized, segment was predicated as the last objective. The Pakistan issue conveyed a positive objective to the Muslims and streamlined the undertaking of political fomentation. It was not any more important to remain "burdened" to Hindus, and the revised wording of the Lahore Resolution issued in 1940 required a "brought together Pakistan." It would, in any case, be tested by eastern Bengalis in later years.

After 1940 compromise amongst Congress and the Muslim League turned out to be progressively troublesome. Muslim excitement for Pakistan developed in guide extent to Hindu judgment of it; the idea went up against its very own existence and turned into a reality in 1947.

Amid World War II, the Muslim League and Congress embraced distinctive mentalities toward the British government. At the point when in 1939 the British proclaimed India at war without first counseling Indian legislators, Muslim League government officials took after a course of restricted participation with the British. Authorities who were individuals from Congress, be that as it may, surrendered from their workplaces. At the point when in August 1942 Gandhi propelled the progressive "Quit India" development against the British Raj, Jinnah denounced it. The British government countered by capturing around 60,000 people and prohibiting Congress. In the interim, the Muslim League ventured up its political action. Public interests ascended, as did the occurrence of mutual brutality. Talks amongst Jinnah and Gandhi in 1944 demonstrated as vain as did the transactions amongst Gandhi and the emissary, Lord Archibald Wavell.

In July 1945 the Labor Party came to control in Britain with a dominant part. Its decisions in India were constrained by the decay of British power and the spread of Indian agitation, even to the furnished administrations. Some type of autonomy was the main contrasting option to coercive maintenance of control over an unwilling reliance. The emissary had talks with Indian pioneers in Simla in 1945 trying to choose what frame a break government may take, however no understanding developed.

New races to commonplace and focal lawmaking bodies were requested, and a three-man British bureau mission touched base to talk about plans for India's self-government. In spite of the fact that the mission did not specifically acknowledge plans for self-government, concessions were made by seriously restricting the intensity of the focal government. A break government made out of the gatherings returned by the decision was to begin working promptly, just like the recently chose Constituent Assembly.

Congress and the Muslim League rose up out of the 1946 race as the two prevailing gatherings. The Muslim League's achievement in the decision could be measured from its breadth of 90 percent of every single Muslim seat in British India—contrasted and a unimportant 4.5 percent in 1937 races. The Muslim League, similar to Congress, at first acknowledged the British bureau mission design, notwithstanding grave reservations. Consequent question between the pioneers of the two gatherings, be that as it may, prompted doubt and intensity. Jinnah requested equality for the Muslim League then government and incidentally boycotted it when the request was not met. Nehru carelessly made explanations that cast questions on the genuineness of Congress in tolerating the bureau mission design. Each gathering questioned the privilege of the other to name Muslim pastors.

At the point when the emissary continued to frame an interval government without the Muslim League, Jinnah called for exhibits, or "direct activity," on August 16, 1946. Public revolting on an uncommon scale broke out, particularly in Bengal and Bihar; the slaughter of Muslims in Calcutta conveyed Gandhi to the scene. His endeavors quieted fears in Bengal, however the revolting spread to different areas and proceeded into the next year. Jinnah brought the Muslim League into the administration trying to keep extra common savagery, yet contradiction among the clergymen rendered the between time government incapable. Over all lingered the shadow of common war.

In February 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten was delegated emissary and was offered guidelines to orchestrate the exchange of intensity. After a snappy evaluation of the Indian scene, Mountbatten said that "India was a ship ablaze in mid-sea with ammo in her hold." Mountbatten was persuaded that Congress would acknowledge segment as the cost for halting carnage and that Jinnah was eager to acknowledge a littler Pakistan. Mountbatten got endorse from London for the radical activity he proposed and afterward influenced Indian pioneers to submit for the most part to his arrangement.

On July 14, 1947, the British House of Commons passed the India Independence Act, by which two autonomous territories were made on the subcontinent and the regal states were left to agree to either. All through the late spring of 1947, as mutual savagery mounted and dry spell and surges racked the land, arrangements for segment continued in Delhi. The arrangements were deficient. A rebuilding of the military into two powers occurred, as peace separated in various parts of the nation (see Pakistan Era, ch. 5). Jinnah and Nehru attempted unsuccessfully to suppress the interests that neither completely understood.Jinnah flew from Delhi to Karachi on August 7 and took office seven days after the fact as the primary representative general of the new Dominion of Pakistan.

Pakistan Period, 1947—71.

Transition to Nationhood, 1947—58.

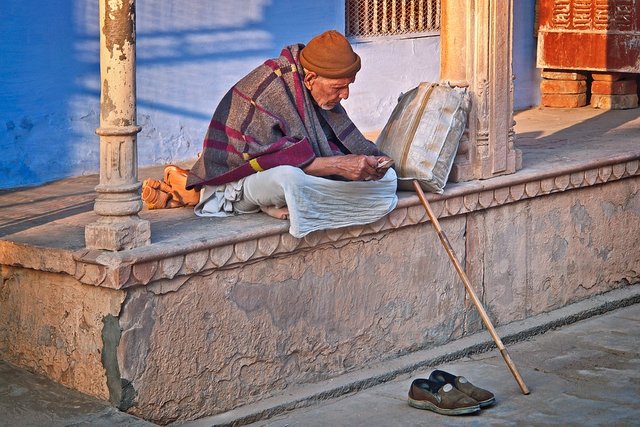

Pakistan was conceived in slaughter and appeared on August 15, 1947, stood up to by apparently impossible issues. Upwards of 12 million individuals—Muslims leaving India for Pakistan, and Hindus and Sikhs picking to move to India from the new province of Pakistan—had been engaged with the mass exchange of populace between the two nations, and maybe 2 million displaced people had kicked the bucket in the collective bloodbath that had went with the relocations. Pakistan's limits were set up quickly without satisfactory respect for the new country's monetary reasonability. Indeed, even the negligible prerequisites of a working focal government—talented staff, gear, and a capital city with government structures—were absent. Until 1947 the East Wing of Pakistan, isolated from the West Wing by 1,600 kilometers of Indian region, had been intensely subject to Hindu administration. Numerous Hindu Bengalis left for Calcutta after segment, and their place, especially in business, was taken generally by Muslims who had relocated from the Indian province of Bihar or by West Pakistanis from Punjab.

After parcel, Muslim managing an account moved from Bombay to Karachi, Pakistan's first capital. A significant part of the interest in East Pakistan originated from West Pakistani banks. Speculation was moved in jute generation when universal request was diminishing. The biggest jute preparing production line on the planet, at Narayanganj, a modern suburb of Dhaka, was possessed by the Adamjee family from West Pakistan. Since keeping money and financing were for the most part controlled by West Pakistanis, unfair practices frequently came about. Bengalis ended up rejected from the administrative level dry from gifted work. West Pakistanis tended to support Urdu-speaking Biharis (displaced people from the northern Indian province of Bihar living in East Pakistan), viewing them as less inclined to work unsettling than the Bengalis. This inclination turned out to be more articulated after unstable work dashes between the Biharis and Bengalis at the Narayaganj jute process in 1954.

Pakistan had an extreme lack of prepared authoritative staff, as most individuals from the preindependence Indian Civil Service were Hindus or Sikhs who picked to have a place with India at parcel. Rarer still were Muslim Bengalis who had any past managerial experience. Accordingly, abnormal state posts in Dhaka, including that of representative general, were typically filled by West Pakistanis or by outcasts from India who had embraced Pakistani citizenship.

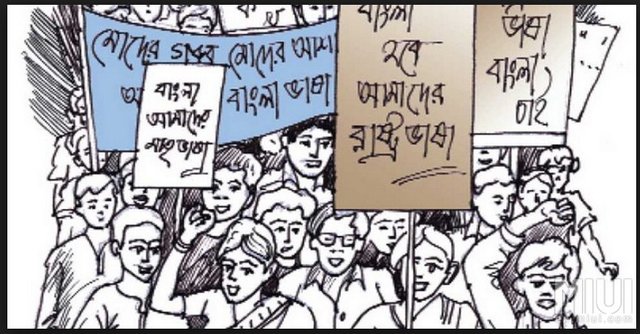

A standout amongst the most disruptive issues going up against Pakistan in its earliest stages was the topic of what the official dialect of the new state was to be. Jinnah respected the requests of displaced people from the Indian conditions of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, who demanded that Urdu be Pakistan's authentic dialect. Speakers of the dialects of West Pakistan—Punjabi, Sindhi, Pushtu, and Baluchi—were vexed that their dialects were given inferior status. In East Pakistan, the disappointment immediately swung to viciousness. The Bengalis of East Pakistan constituted a larger part (an expected 54 percent) of Pakistan's whole populace. Their dialect, Bangla (at that point usually known as Bengali), shares with Urdu a typical SanskriticPersian predecessor, however the two dialects have distinctive contents and artistic customs.

J innah went to East Pakistan on just a single event after freedom, in the blink of an eye before his passing in 1948. He declared in Dhaka that "without one state dialect, no country can remain emphatically together and work." Jinnah's perspectives were not acknowledged by most East Pakistanis, but rather maybe in tribute to the organizer of Pakistan, genuine obstruction on this issue did not break out until after his passing. On February 22, 1952, an exhibit was completed in Dhaka in which understudies requested equivalent status for Bangla. The police responded by terminating on the group and slaughtering two understudies. (A remembrance, the Shaheed Minar, was fabricated later to celebrate the saints of the dialect development.) Two years after the episode, Bengali unsettling successfully constrained the National Assembly to assign "Urdu and Bengali and such different dialects as might be proclaimed" to be the official dialects of Pakistan.

What kept the new nation together was the vision and mighty identity of the originators of Pakistan: Jinnah, the senator general famously known as the Quaid I Azam (Supreme Leader); and Liaquat Ali Khan (1895—1951), the principal head administrator, prevalently known as the Quaid I Millet (Leader of the Community). The administration hardware built up at autonomy was like the viceregal framework that had won in the preindependence period and set no formal constraints onJinnah's sacred forces. In the 1970s in Bangladesh, another dictator, Sheik Mujibur Rahman, would appreciate a significant part of a similar eminence and exception from the typical control of law.

At the point when Jinnah passed on in September 1948, the seat of intensity moved from the senator general to the executive, Liaquat. Liaquat had broad involvement in legislative issues and delighted in as a displaced person from India the extra advantage of not being too firmly related to any one region of Pakistan. A direct, Liaquat bought in to the beliefs of a parliamentary, fair, and mainstream state. Out of need he considered the desires of the nation's religious representatives who championed the reason for Pakistan as an Islamic state. He was looking for an adjust of Islam against secularism for another constitution when he was killed on October 16, 1951, by devotees contradicted to Liaquat's refusal to take up arms against India. With both Jinnah and Liaquat gone, Pakistan confronted a flimsy period that would be settled by military and common administration mediation in political issues. The initial couple of turbulent years after freedom hence characterized the persisting politico-military culture of Pakistan.

The failure of the legislators to give a steady government was generally a consequence of their shared doubts. Loyalties had a tendency to be close to home, ethnic, and commonplace as opposed to national and issue situated. Provincialism was transparently communicated in the considerations of the Constituent Assembly. In the Constituent Assembly visit contentions voiced the dread that the West Pakistani region of Punjab would rule the country. An ineffectual body, the Constituent Assembly took right around nine years to draft a constitution, which for every handy reason for existing was never put into impact.

Liaquat was prevailing as PM by a preservationist Bengali, Governor General Khwaja Nazimuddin. Previous fund serve Ghulam Mohammad, a Punjabi vocation government worker, progressed toward becoming senator general. Ghulam Mohammad was disappointed with Nazimuddin's powerlessness to manage Bengali fomentation for common self-rule and attempted to extend his own capacity base. East Pakistan supported a high level of self-governance, with the focal government controlling minimal more than remote undertakings, safeguard, correspondences, and money. In 1953 Ghulam Mohammad expelled Prime Minister Nazimuddin, built up military law in Punjab, and forced representative's run (coordinate administer by the focal government) in East Pakistan. In 1954 he named his own "bureau of abilities." Mohammad Ali Bogra, another preservationist Bengali and already Pakistan's envoy to the United States and the United Nations, was named head administrator.

Amid September and October 1954 a chain of occasions finished in an encounter between the senator general and the head administrator. Head administrator Bogra endeavored to restrict the forces of Governor General Ghulam Mohammad through quickly received alterations to the true constitution, the Government of India Act of 1935. The representative general, be that as it may, enrolled the implied support of the armed force and common administration, broke down the Constituent Assembly, and after that framed another bureau. Bogra, a man without an individual after, stayed head administrator yet without compelling force. General Iskander Mirza, who had been an officer and government worker, moved toward becoming pastor of the inside; General Mohammad Ayub Khan, the armed force leader, progressed toward becoming clergyman of barrier; and Choudhry Mohammad Ali, previous leader of the common administration, remained priest of back. The primary target of the new government was to end troublesome common legislative issues and to give the nation another constitution. The Federal Court, anyway pronounced that another Constituent Assembly should be called. Ghulam Mohammad was not able go around the request, and the new Constituent Assembly, chose by the common congregations, met without precedent for July 1955. Bogra, who had little help in the new get together, fell in August and was supplanted by Choudhry; Ghulam Mohammad, tormented by weakness, was prevailing as representative general in September 1955 by Mirza.

The second Constituent Assembly contrasted in arrangement from the first. In East Pakistan, the Muslim League had been overwhelmingly crushed in the 1954 commonplace get together races by the United Front coalition of Bengali territorial gatherings tied down by Fazlul Haq's Krishak Sramik Samajbadi Dal (Peasants and Workers Socialist Party) and the Awami League (People's League) driven by Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy. Dismissal of West Pakistan's strength over East Pakistan and the craving for Bengali common self-rule were the primary elements of the coalition's twentyone-point stage. The East Pakistani decision and the coalition's triumph demonstrated pyrrhic; Bengali factionalism surfaced not long after the race and the United Front went into disrepair. From 1954 to Ayub's suspicion of intensity in 1958, the Krishak Sramik and the Awami League pursued an endless fight for control of East Pakistan's common government.

Executive Choudhry actuated the legislators to concur on a constitution in 1956. Keeping in mind the end goal to set up a superior harmony between the west and east wings, the four regions of West Pakistan were amalgamated into one regulatory unit. The 1956 constitution made arrangements for an Islamic state as epitomized in its Directive of Principles of State Policy, which characterized strategies for advancing Islamic profound quality. The national parliament was to include one place of 300 individuals with level with portrayal from both the west and east wings.

The Awami League's Suhrawardy succeeded Choudhry as head administrator in September 1956 and shaped a coalition bureau. He, as other Bengali legislators, was picked by the focal government to fill in as an image of solidarity, yet he neglected to anchor critical help from West Pakistani power dealers. Despite the fact that he had a decent notoriety in East Pakistan and was regarded for his prepartition relationship with Gandhi, his strenuous endeavors to increase more noteworthy common self-sufficiency for East Pakistan and a bigger offer of improvement stores for it were not generally welcomed in West Pakistan. Suhrawardy's thirteen months in office reached an end after he took a solid position against revocation of the current "One Unit" government for all of West Pakistan for isolated neighborhood governments for Sind, Punjab, Baluchistan, and North-West Frontier Province. He accordingly lost much help from West Pakistan's commonplace legislators. He additionally utilized crisis forces to keep the development of a Muslim League commonplace government in West Pakistan, along these lines losing much Punjabi backing. In addition, his open support of votes of certainty from the Constituent Assembly as the best possible methods for framing governments excited the doubts of President Mirza. In 1957 the president utilized his impressive impact to expel Suhrawardy from the workplace of executive. The float toward financial decay and political disarray proceeded.

You have been defended with a 32.21% upvote!

I was summoned by @mamunjm.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Great effort

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

tnq

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

This is nice, good historical article. Thanks a lot @mamunjm i really appreciate this. Keep steeming.....

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

welcome

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

In pakistan we had same history👍👍

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

no worries I will bring all things step by step

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Great post!

Thanks for tasting the eden!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit