Now the serpent was more crafty than any of the wild animals the LORD God had made. He said to the woman, "Did God really say...?"

In Part 1, I examined claims that modern Bibles are being changed to support a New World Order (NWO) agenda. I extracted the most compelling examples from a referenced documentary video and posted some of the changes I had verified. Then I analyzed what the worst case doctrinal impact might be for each change. I decided to go back to the King James Version (KJV) as a result.

In Part 2, I examine the alternative best case scenario giving those nefarious revisionists the benefit of the doubt. What exactly are the competing methodologies and documents used to get to today's leading Bible versions? Are they fair and reasonable? Do they really impact doctrine? To my surprise, the body of reconstructed Greek texts are all in solid agreement at the doctrinal level. But I'm still keeping my King James...

to exactly one mutually reinforcing pair of doctrinally compatible reference texts.

That is, you can switch between the two major schools of Greek Bible reconstruction (Alexandrian Critical Text vs. Byzantine Majority Text) without losing support for the key precepts of Biblical Christianity. That doesn't mean that the various sects of Christianity won't continue to disagree on what the Greek reference texts actually mean. It just suggests that we can reasonably continue our arguments in English using any of the currently most popular versions (KJV, NKJV, NIV, ESV or NLT) that have been derived from them. This agreement does not extend as much to the Latin Vulgate used by the Roman church, nor does it imply that we will agree on any extra-Biblical doctrines that have crept into the teachings of various denominations.

...But it is a convenient place to take a stand.

Brief overview of the leading original Greek reconstruction methodologies.

Without getting too technical, let me quickly summarize how the original Greek New Testament has been reconstructed according to the leading schools of thought.

Interest in Greek Bible texts surged in the 1500s when early Protestant reformers began to suspect that the Popes were "embellishing" what the Scriptures said for various reasons (mostly wealth and power) and keeping the Scriptures locked up in the dead language of Latin where nobody could check them on it. They sought out an independent verification by going back to the original Greek, preferably from sources outside the Vatican.

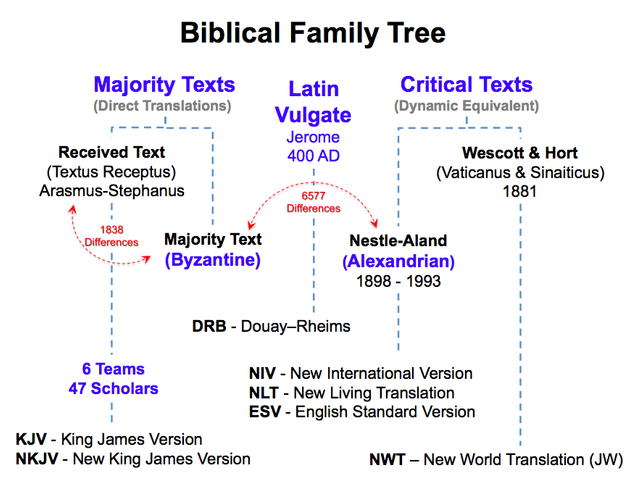

In 1516, a brilliant linguist named Arasmus collected all the Greek manuscripts he could find (about six) and used them to produce a composite reference text called the Textus Receptus (Received Text) which compared that composite Greek to the official Latin Vulgate text from the Roman Church. Martin Luther used this to produce a German Translation and William Tyndale did the same for English. This launched a process of increasingly precise translations that culminated 100 years later in the King James Bible.

Arasmus (mostly) used a methodology that became known as Majority Text analysis which essentially allowed each Greek manuscript to vote, word by word, on what went into the resulting Textus Receptus. Since that time, work has continued adding more and more manuscripts to the mix, resulting in an updated version of Textus Receptus called simply the Majority Text. There are 1838 minor differences between Textus Receptus and Majority Text - but they are mostly spelling and word order differences - nothing of doctrinal importance. For this reason and to preserve historical tradition, no popular translation actually uses the Majority Text and today's King James Version and the modern english New King James Version (NKJV) both continue to use the Textus Receptus as their basis.

The Textus Receptus and Majority Text tend to favor Greek texts that came out of Turkey when Christians fled ahead of the Muslim armies in the 1400's. Hence, these are often referred to as the Byzantine Majority Text reference Greek.

But there is another source of Greek manuscripts that generally come from the dry climate south of the Mediterranean which have generally been preserved longer. These "Alexandrian" texts are preferred by another school of thought called Alexandrian Critical Text Method. Rather than letting the Alexandrian manuscripts "vote" on every work, scholars prefer to manually analyze and debate each word based on additional factors including "external evidence" (age, care, provenance, affiliation, and quotes from other documents and languages) and "internal evidence" ("shorter, less-polished readings are better", "author's writing style", etc.) Most popular modern Bible versions (NIV, NLT, ESV, NWT, et. al) use the Alexandrian Critical Text as a reference.

Meanwhile, the Vatican continues to stick with its Latin Vulgate which Jerome translated from his Greek resources circa 400 AD. This is the reference Latin on which the modern Douay-Rheims translation is based.

The family tree that leads to today's leading versions is shown below.

One other difference between the schools of thought is that English Translations derived from the Byzantine Majority Text school (KJV, NKJV) are word for word "direct translations" where as those from the Alexandrian Critical School (NIV, NLT, ESV) are phrase by phrase or sentence by sentence "dynamic equivalents".

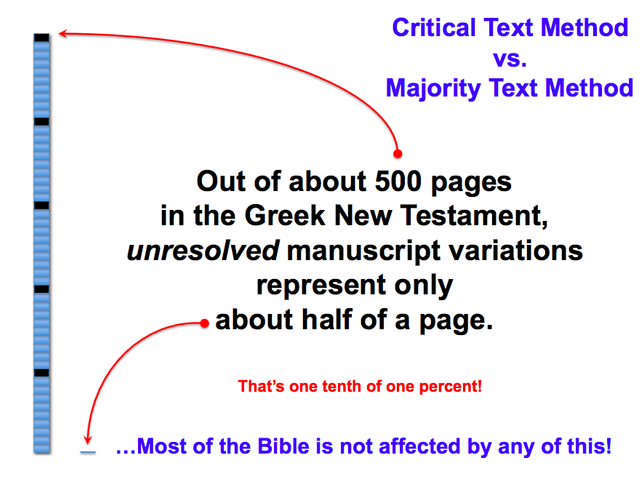

There are 6577 trivial differences (mostly spelling, word order, etc.) between these two Greek Reference Texts. The biggest difference is the tendency of the Critical Text to leave out an occasional verse or phrase on the theory that scribes were more likely to add than subtract when making copies.

Back in Part 1 I enumerated and commented on the most worrisome of these differences. My many comments in that post discussion reflect my subsequent thoughts about it - stimulated by the helpful comments from others that I received there.

Resulting Conclusions.

Based on what I have learned from the discussion in Part 1 and my subsequent deeper study, I offer the following personal opinions for your consideration:

- I still don't like the revisionist trend. It can lead to mischief (inserting translator preferences).

- The revisions so far don't affect doctrine and amount to a tiny fraction of a percent of the overall text. Thus the current status of the most popular translations I looked at is tolerable and perhaps even better if the translators have really been faithful.

- As an engineer, I prefer the Critical Text method better the Majority Text method because it weighs more factors in the balance and avoids the potential of having the tyranny of the majority override common sense.

- I don't generally trust academic "scholars" to apply the Critical Text method without inserting their own secular or parochial agendas. There are, no doubt, honest scholars among them, but I can't tell which is which and I never trust the majority opinion on anything.

- The King James Version translators, of course, had their own open agenda too. But it is the same as mine. Sola Scriptura. They were looking to find the truth once they were convinced they couldn't trust the recklessly presumptive inventions of the popes. Subsequently derived Protestant doctrine followed the Textus Receptus, not the other way around.

- As time progresses, I expect more and more "corrections" that implement hidden agendas that will begin to affect the original doctrine.

- Therefore, it is better to live with the relatively harmless errors in the King James Version than to encourage the average student to wander off into the most popular paraphrased Text du Jour.

- Serious students willing to put in the time can benefit from discussing the fine points brought out by scholarly debate.

Bottom Line It is currently fairly safe for people of faith who aren't very curious can simply accept the mainstream Bibles I studied at face value. Those of us cursed with the need for details can find them and be satisfied! Among the authors I consulted, several agreed that for nearly 200 years there has been almost complete unanimity among those diverse schools of thought that none of those cosmetic differences between the Greek texts affects doctrine (i.e. the definition of Biblical Christianity). The Latin Vulgate, not so much.

We are still not out of the woods

What does effect doctrine is what people do with those reference Greek texts after the fact. Different people will read and emphasize different parts while ignoring other parts to arrive at their own personal preferences and can thereby wander off arbitrarily far from the truth. Or they will blatantly claim that their leaders have the authority to alter the teachings of people who knew Jesus. Many sects, having wandered away to some such non-negotiable position, then go back and modify their Bibles to match their doctrine. As soon as they do that they are permanently lost.

However, I am now fairly satisfied that, despite their cosmetic differences, the versions I examined (KJV, NKJV, NIV, NAS, ESV) are currently safely inside the bounds of a common doctrine which can be called "Biblical Christianity". Personally, I stick with KJV because it is not subject to further second guessing that could lead outside the common reference definition due to politically correct secular pressures in the future.

Nevertheless, I must repeat:

to exactly one mutually reinforcing pair of doctrinally compatible reference texts.

This is good, because now we can focus on debating in forums like this whether a particular issue is faithful to these unanimous reference texts. At this point I am able to participate with results from my own studies and learn from the studies of others. Now I can point to several English versions which are authoritative enough to construct a Scripture based debate upon.

Such debates are fine and healthy and can lead to a deeper understanding for all concerned.

Reference Links

What about the Majority Text?

Majority Text and Original Text, Are They Identical?

English Bible History and Timeline

List of Major Textual Variants in the New Testament

Interview with Daniel B. Wallace on the New Testament Manuscripts

Some Second Thoughts on the Majority Text

25,000 New Testament Transcripts? Big Deal.

Bible Version Comparison Chart

Westcott & Hort vs. Textus Receptus: Which is Superior?

Another point I found compelling is this:

The little things the two schools of thought find to argue about says a LOT about what they do NOT argue about.

This means that the common critic's claim that Scriptures have been corrupted beyond recognition due some variant of the old "telephone game" of successive copies diverging is overwhelmingly denied by the lack of arguments about them.

Where are these corruptions?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I've noted many of these corruptions already, and I've demonstrated that, contrary to your contentions, they were material, substantive and influenced the evolving Christian doctrines. But, even so, it's likely that we've uncovered only a small portion of these "corruptions". Why? Becasue we know for a fact that they were sytematically and ruthlessly supressed starting during the time of Constantine.

Prior to Constantine's conversion, Rome had ruthlessly and systematically supressed Christianity, right? Every Christian remembers the times of the "martyrs". They have no problem appreciating the full extent of its horidness.

And yet, these same Christians naively believe that once Constantine converted, he embraced all forms of Christianity. He didn't. Rather, he called the Nicene Council to resolve the many and varied disputes within Christianity and to create a standard Christian doctrine for once and all. That doctrine was then enforced with the same ferocity, in fact more ferocity, over the subsequent centuries that Rome had originally directed toward Christians in general.

In other words, once the canon started to become fixed during the time of Constantine, "heretical" documents were systematically destroyed at worst or simply ignored (that is, not copied for posterity) at best. Versions of the cononical gospels that differences from those endorsed by Rome (such as, perhaps, the original Matthew which was written in Hebrew) and the original Mark (which contained only "sayings of the Lord" though "not in order") disappeared over the subsequent centuries.

Having said that, I would not be surprised if some of them are eventually found. Remember, it's only been within the last century that the Nag Hamadi Library and the Dead Sea Scrolls were both discovered, and they contained a great many "heretical" Christian/Jewish texts that had been supressed nearly out of existence. It would not be surprising for someone to one day stumble upon the original Matthew or the original Mark, or perhaps Luke or John or versions of the letters of Paul that differ markedly from our received ones. Given the extent of the suppression, the odds are not great, but with the passage of sufficient time, it's possible.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

While I certainly don't condone the actions of the popes throughout history, there was nothing in principle wrong with gathering the leaders of Christianity together at multiple conferences over the centuries to address issues of controversy and weed out teachings deemed to be false by the majority. The alternative is to allow false teachings to proliferate without bound.

Acts 15 describes the first of these councils in Jerusalem with the actual apostles present which serves as a model and an implicit endorsement of the process.

I will concede that at each of these major events we are counting on the Holy Spirit to oversee the decisions that were made under the doctrine that inspired scripture must be preserved the same way if it is to reach us so that we can obey it as commanded. This is an article of faith backed up by the Scriptures that Jesus Himself endorsed.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

That was a lot of work. Upvoted :)

I too was a bit perplexed by the 70 or so interpretations of the English Word. I live in South America and have witnessed similar debates about the 20 or so interpretations that exist in Spanish as well.

I have chosen to learn the letters in Hebrew and start there. I have plugged along with Hebrew for quite some time and am well into the second book of the Tenak - uninterpreted. The depth that has been added to my understanding of scripture is amazing. Understand that all Greek, Latin, Spanish, etc. bibles are not word for word. Reading the word for word "translation" carries genders and pronouns for speaker as well as listener in the original language. One cannot make sense of most scripture if reading a translation - if it's accurate.

Reading left to right, you will see what I mean below

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Very interesting!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Good info.

Quick correction - ESV is not dynamic equivalent. It is word for word as much as the NAS, NKJV or KJV.

NIV is dynamic equivalent. NLT is a paraphrase written to help children learn and was never meant to be adopted as a translation. But it sells.

There is an interesting angle to this discussion that many miss as well, having to do with the doctrinal position of translators. The NASB was translated by mostly dispensationalists. The ESV translators, led by Packer, were largely covenantalists. When one realizes this, the nuances can be picked up in certain passages.

The political motivations King James are interesting as well, if one is willing to dig deeply enough. The Geneva Bible wasn't inferior in its accuracy, but there were some interesting "adaptations" embraced by the "authorized" translators.

As you noted, there aren't really any doctrinal issues with these translations. While the Johannine comma is certainly debatable (I think history makes it clear that it was added during the Reformation), the doctrine of the Trinity hardly needs it. As far as I know, that's the only one that might even be on the table as a concern.

Enjoy your studies. They're certainly worthwhile and enriching.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I do have a question, why are we referring to Greek and Latin texts, shouldn't the originals have been in Hebrew or Aramaic, making any other text just a translation and subject to mistakes? I am no student of the bible I am just asking because I have been led to believe the originals were written in Palestine, were the popular languages were not Greek or Latin.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Old Testament was written in Hebrew/Aramaic

New Testament was all written in Greek

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Not exactly. Whenever Paul quoted the Old Testament, he quoted from Greek (mis)translations of it.

Furthermore, attribution of “Matthew” to Jesus' disciple of the same name is based solely on the testimony of Papias, who tells if via Eusebius' Church History that:

So, the earliest versions of Matthew (at least) were in fact written in Hebrew, not Greek.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yes, but why should that be? The people who knew about this weren't Greeks, and as far as I know Greek wasn't the common language in Palestine. It should have been written in Hebrew or Aramaic, if it is in Greek it is just what somebody wrote about what he heard.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Much of the New Testament was written to people in Galatia, Philippi, Thessalonica, Corinth, Ephesis and Rome. Greek was the primary language throughout much of this area, especially for intellectual discourse.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

But again the original was not in Greek.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Well, even though Paul was arguably the most literate person in his generation "advancing in Judaism ahead of all his peers" he still used a scribe to write many of his letters. Similarly, John Mark served as a scribe to write down what Peter had to say. Luke was a Greek from Troas, Turkey. John spent most of his last thirty years living in Ephesus, Turkey, no doubt speaking Greek. Revelation was addressed to seven Greek speaking churches in Turkey.

"Everybody" spoke Greek the way "everybody" speaks English in the world today in addition to their native languages. So it was entirely natural for the letters and gospels to be written in the official international language of that day - especially when most of them were addressed to people outside Judea.

Since the apostles were given the Great Commission by Jesus to "make disciples of all nations", it would not make any sense have chosen to do that in Hebrew or Aramaic anyway.

Even the Old Testament had been independently translated into Greek (Septuagint) by 72 Jewish Scholars commissioned by King Ptolemy of Egypt. It became the standard translation in use throughout the world for hundreds of years surrounding the time of Christ.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

What evidence do you have of that? Paul spoke Hebrew, Aramaic, Latin and Greek and many of his Gentile companions (e.g Luke and Timothy) were Greek and most of the churches he started were Greek.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

The Greeks had ruled the region for hundreds of years since Alexander the Great. Rome was a relative newcomer in 63 BC. The common language changes much slower than armies move.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Because the actors in this were Hebrews, whatever they said they did not say it in Greek, so whatever Paul wrote in Greek or whatever language, he had to have heard it first in Hebrew or Aramaic, therefore in his translation much could have been lost or added. And the important part of the New Testament isn't what the others wrote it is what Jesus said, and if you have to rely on various translations I just think you will have mistakes made. Apart from this, how many people of that time were able to read and write? I bet you anyone who was literate could write whatever he wanted and pass it off as what the oral traditions said.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

OK, even though I am not too convinced about Greek being the universal language then, it should have been Latin as Rome ruled.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

The Romans conquered Greece in the year 146 BC, so I think language should have started changing since then. Alexander conquered Palestine around 333 BC, I don't think your answer is too convincing, as Latin already had nearly 200 years to become the official language.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Yes. Hebrew was the original - Aramaic is very close to it. One popular "manner of speech" seen throughout the new testament reads, 'and he spoke to them, saying..." which is a Hebrew structure. Tons of evidence is seen when Jesus spoke to Paul after knocking him to the ground blind "in Hebrew."

Good point. We should concentrate on actually completing a pass of the entire bible before we start arguing foreign languages and pet verses. When read, the new testament is interpreted perfectly by the old testament as your right hand, by design, folds into your left.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Maybe this will help: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Language_of_the_New_Testament

"Koine Greek, the common language of the Eastern Mediterranean[3][4][5][6] from the Conquests of Alexander the Great (335–323 BC) until the evolution of Byzantine Greek (c. 600)."

and

"The New Testament Gospels and Epistles were only part of a Hellenistic Jewish culture in the Roman Empire, where Alexandria had a larger Jewish population than Jerusalem, and Greek was spoken by more Jews than Hebrew."

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

OK, you say Greek was the official language, fine, but what language did Jesus and his followers speak? So all that I said from the start regardless if you say it was Greek or Latin what we have in the bible are translations from the original Hebrew or Aramaic, and in translations something is always lost or added.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

It doesn't matter what language the original version was written in because that is the inspired version. If it is inspired then it is accurate irregardless of the language. If you don't believe in the inspiration of Scripture, then again it doesn't matter if it was written in Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, or Latin. Then it is just another book and we shouldn't even bother talking about it.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Ok, then I will just ask you two more questions which one of the many versions is the inspired one, and why do you think that version is the correct one?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Only the original is inspired.

Here is a good discussion of that issue: https://gotquestions.org/translation-inspiration.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

What do you think of James White's critique of the King James and the newer versions?

Also, considering your propensities for specificity, wouldn't it be best for you to learn the Biblical languages and read the compiled works? Im asking from ignorance, so please take that into account.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Got a link?

If I were 40 years younger, I would study the languages. As it is now, I use the tools I find in my hands.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

There are a few debates, which are quite lengthy (an hour or two)

The best are here :

and here:

His book on the subject is the "King James Only Controversy"

https://www.amazon.com/King-James-Only-Controversy-Translations/dp/0764206052

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Also, after looking at my comment, it sounds a bit snarky, which was unintentional. I apologize for that.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit