When the early Internet was being built, a philosophical question emerged: who should own the software? The radical fringe of the hippie generation of the 1960s, which crossed in places into the area occupied by scientists and programmers, dreamed up the idea of the personal computer, and then began dreaming of ways to link them together.

In the early 1980s, activist and programmer Richard Stallman helped found the Free Software Movement, arguing that software should not be proprietary, but should be free to distribute. It’s a scenario that has played out many times in the development of the internet, between closed and open source software, or between free and proprietary software. Internet Explorer, for example, is proprietary software, as is Windows. (Firefox and Linux, for instance, are developed from open source software.)

The philosophy of the movement is that the use of computers should not lead to people being prevented from cooperating with each other. In practice, this means rejecting "proprietary software", which imposes such restrictions, and promoting free software, with the ultimate goal of liberating everyone in cyberspace – that is, every computer user. By the late 1990s, free software - which defined itself as a social movement - had evolved (or devolved, depending on your viewpoint) into open source software, which some dubbed a methodology rather than a movement.

In 1989, British scientist Tim Berners-Lee, who was working at CERN, the European Centre for Nuclear Research, proposed an idea that he called the World Wide Web. The idea of the World Wide Web was to use computers to connect together academics and scientists for the easy sharing of information. The first website was hosted on Berners-Lee’s own computer, so in 1991 CERN became the first widely recognised website and in 1993 CERN released the worldwide web software into the public domain.

The growth of the internet during the 1990s offered access to thousands of pages of content on the web. The initial impulse of users was to share information, so at first, most internet users worked with the FTP (File Transfer Protocol) to upload and transfer files across the web. The release of the Mosaic browser in 1993 - based on code written by Marc Andreessen - later to become a famous investors - made the web accessible for ordinary users. By 1995, WWW overtook FTP as the service with the most traffic on the internet, and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Netscape competed for traffic. The widely-adopted suite of protocols - Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) - that allowed computers to connect to the internet became the standard internet protocol, governing the rules of how data is addressed.

But the early promise and hope of a diverse and multifaceted internet faded as private companies realised the potential of the internet. From the mid-1990s across the turn of the millennium and into 2001, the growth in usage of the internet saw millions of companies add a “.com” to their names, trying to ride the “network effect”. Investors poured into the new “dotcom" phenomenon, but the promise proved ephemeral and the market imploded in 2001. Not that all companies lost out. The rise of Google from the late 1990s heralded a new concentration of power on the internet, and in the aftermath of the crash, a handful of resilient companies including Google and Amazon began to slowly dominate the web, joined in 2004 by Facebook, which promised to connect friends and families across the globe. By 2005, one billion people were using the internet. By 2017, that number had grown to 3.5 billion, half of the people on Earth.

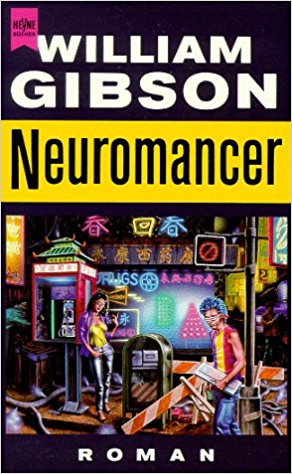

But a handful of people never relented on the early promise. “The future is already here,” said William Gibson, the author of Neuromancer and inventor of the word cyberspace. “It just isn’t evenly distributed.” The influence of Gibson’s first novel lives on in film and literature. (Neuromancer planted the idea for The Matrix, right down to its Zion spaceship, and without Neuromancer’s Molly Millions aka Steppin’ Razor (another Rasta theme), there’s no Lisbeth Salander as the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.) Gibson is credited as the originator of cyberpunk: when a group of Silicon Valley programmers began to gather to discuss the battle over privacy on the internet in the early 90s, they called themselves cypherpunks in tribute. By the late 1990s, their first ideas about internet money started to circulate.

in 1997 the UK cryptographer Adam Back created a programme called HashCash, an attempt to develop an anonymous transaction system, which proposed the use of a proof-of-work, which requires a computationally intensive process. That was followed in 1998 by an idea from Wei Dai called BMoney which proposed a protocol that allowed the creation and exchange of money by untraceable entities rather than by Central Banks. Their ideas were advanced by Hal Finney in 2004 with his paper on Reusable Proofs of Work and by Nick Szabo’s 2005 proposal for Bitgold. Satoshi Nakamoto was following at least some of these developments:

From: "Satoshi Nakamoto" [email protected]

Sent: Friday, August 22, 2008 4:38 PM

To: "Wei Dai" [email protected]

Cc: "Satoshi Nakamoto" [email protected]

Subject: Citation of your b-money page

I was very interested to read your b-money page. I'm getting ready to release a paper that expands on your ideas into a complete working system. Adam Back (hashcash.org) noticed the similarities and pointed me to your site.

Satoshi would be the first to admit that he was standing on the shoulders of giants.