Part 1 of this article series began by outlining a notable event from recent music history. In 2015, the notorious pharmaceutical executive and former hedge fund manager Martin Shkreli bought the sole ownership rights to the latest album of The Wu-Tang Clan. The album was called Once Upon a Time in Shaolin and its unique release was spearheaded by the RZA, defacto leader of The Wu-Tang Clan. With only one album copy in existence, RZA intended to make a public critique about how fans approach music today by frivolously downloading song after song without considering the welfare of the original artist. Since then, Wu-Tang fans around the world have suffered from the fact that the album has been held hostage by Shkreli.

This saga outlined some of the challenges that both artists and fans are facing in the music industry. It also provides an opportunity to highlight how Blockchain technology can offer positive impact — through traceability, compensation, and tokenisation. In Part 2, we examine how music industry economics can evolve through the specific blockchain tool of tokenisation.

People Value Things Differently

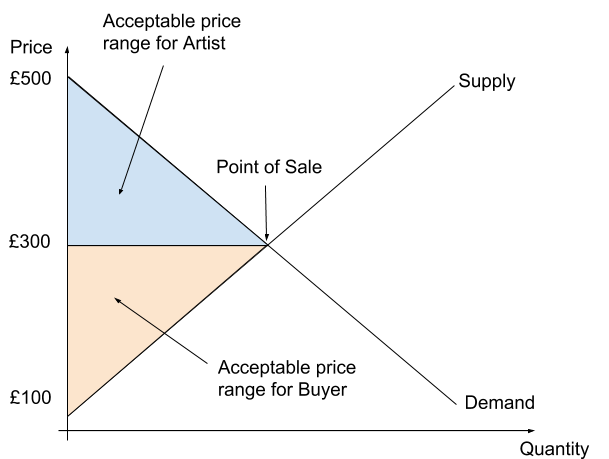

Each buyer and seller has their own preferences about the price they are willing to pay or accept for a given product. Before any given transaction between a buyer and seller, the buyer has their own maximum price at which they are willing to buy a product and the seller has their own minimum price at which they are willing to sell a product.

If an artist (the seller) creates a painting and brings it to an art fair, they may put it on sale for £500 but be willing to negotiate down and sell it for as low as £300. If someone visiting the art fair sees that painting, they may want to pay £100 for the work but can go so far as to pay £300 for the painting. The point of sale is where both the buyer and seller are willing to meet at a price that satisfies them both.

Most of the time the point of acceptable purchase/sale are not equal because people value things differently. So the price of a product is generally decided either through negotiation or based on macro-level supply and demand.

For example, take the price of a bag of oranges.

In scenario 1, you go to a supermarket that lists the price of oranges as £1.50. This is likely based on a variety of factors such as supermarket pricing policy, their current supply of oranges, and how much profit margin the store wants to make. You are not able to negotiate on price so you end up paying £1.50 for the bag of oranges. You are the buyer and the seller is the supermarket.

In scenario 2, you go to a farmer’s market where you are able to talk directly to the farmer who grows the oranges. While the farmer initially says that one bag of oranges costs £1.50, you are able to negotiate the price down to £1.00. You are the buyer and the seller is the farmer. OR, if you are a big fan of oranges and you are a big fan of the farmer, you may pay £2.00 of your sheer enthusiasm for the product and the seller.

Even though the buyers and sellers eventually agree on a price, in practice one person usually wins more value from the transaction relative to how much they truly value the product. We all value things differently. Whether based on our own personal preferences, past experience, or social environment, we are all unique and bring that uniqueness to making purchase decisions.

In scenario 2, depending on how badly you are in the mood for oranges, you may have been willing to spend up to £5 for a bag of oranges. The farmer, for whatever reason, was willing to accept a price of £1.00. Price variation exists in scenario 2 because two people are able to deal with each other directly to appropriately price a transaction that works for both people.

Fans Value Musicians Differently

How does this work in music? Let’s use Justin Bieber instead of a bag of oranges.

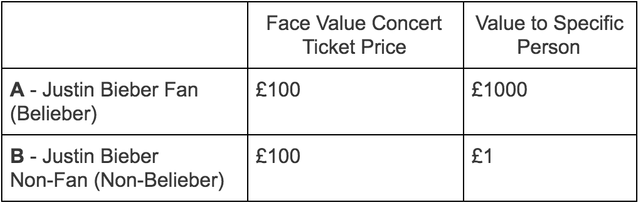

Some people in this world would pay £1000 to see Justin Bieber in concert. Others wouldn’t go to his concert if the tickets were £1 or even if the tickets were free. This is the difference between fans and non-fans.

In the example below, we have Person A and Person B, who each attach a different value to Justin Bieber tickets.

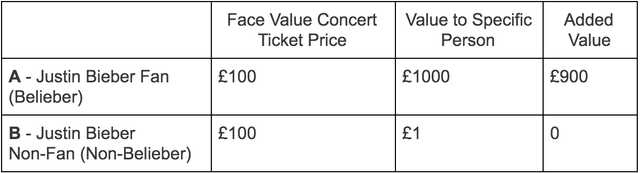

For Person A Belieber, paying £100 for a concert ticket that they would be willing to pay £1000 for means that they are getting a very good deal.

For Person B Non-Belieber, paying £100 for a concert ticket is a terrible deal since they personally value a Justin Bieber ticket at £1.

This next table shows the added value for each person. The fan gets lots of benefit from this situation, and the non-fan receives no benefit. Value is added for the fans but it doesn’t hurt non-fans.

Now picture yourself as a fan entering two different scenarios:

In scenario 1, you go online to a ticketing website and spend £100 on tickets to a Justin Bieber concert, which is a non-negotiable price set by the ticketing website.

In scenario 2, you go directly to Justin Bieber to buy a ticket to his concert and since he sees how big of a Belieber you are, he gives you two tickets for the price of one. Now you have a ticket for both yourself and a fellow Belieber for just £100.

The problem is, scenario 2 doesn’t really exist in the music industry.

Sure, you may have second-hand ticket auctions with varying prices but you generally don’t have direct-to-artist relationships as a consumer, and you generally don’t have direct-to-consumer relationships as an artist. A rare exception to this rule is the artist Ryan Leslie, who we will be examining in Part 3 of this article series.

If every musician had the ability to build a strong, direct relationship with their fans, could they provide different people with different products at different prices? And would this more accurately reflect the actual value people put on music?

To use terms from the field of economics, what I’m highlighting here are producer surplus, consumer surplus and price discrimination. Basically, people value things differently and therefore it makes sense for different things to be priced differently.

Different Values, Different Tokens

The extreme situation between Martin Shkreli and The Wu-Tang Clan highlights this challenge of economics. Martin Shkreli is someone who was willing to pay literally millions of dollars for a Wu-Tang Clan album. So how can we price or value art appropriate to each person’s preferences?

The answer comes from tokenisation, enabled by blockchain technology. This doesn’t solve all problems, but it is a step in the right direction.

Particularly in the world of art and creativity, the relative value each of us puts on artwork can vary dramatically. You see these consumer preferences play out especially in the music industry since music is such a personal topic tied to our own identity. That’s why some concerts can make you excruciatingly bored and other concerts can be the best nights of your life.

So if The Wu-Tang Clan released a Wu-Tang Token, as I explored in Pt. 1, they would be issuing a unit of value attached to The Wu-Tang Clan. One token could provide you access to special events, merchandise, retail partnerships, offers, membership, or anything else The Wu-Tang Clan would want to provide in this direct-to-fan relationship. The market value of a token would be based on supply and demand, and may rise and fall depending on the overall success of the group’s activities. If Wu-Tang Clan releases 1 billion tokens into the market at a price of £0.01 per token, you could invest in the Wu-Tang entity with the intention of funding their business & art and hopefully get a return on your investment by increasing the overall token price. As the musical group, you now have a new way to communicate directly with your fans and more data about what they are willing to pay for different artistic projects. The potential user data attached to a token (with that data given voluntarily) could be the strongest possible feedback loop for artists to understand what their fans really want. I suspect some super fans would be more willing to share intimate data with their favorite artists than the government.

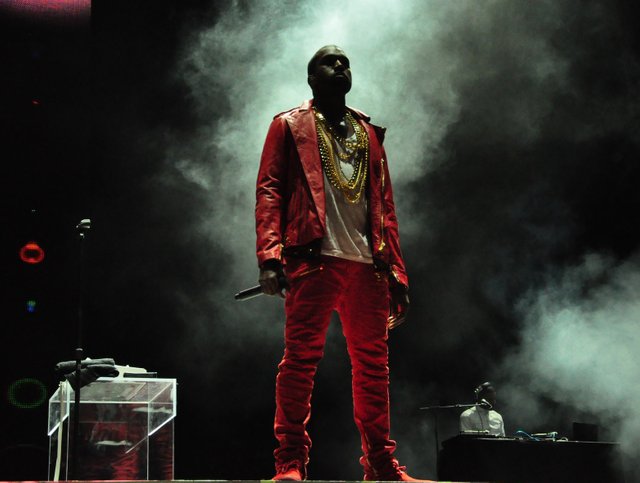

Even if Martin Shkreli was able to spend $2 million worth of his own money on buying Wu-Tang Tokens, this doesn’t make Wu-Tang Tokens inaccessible to everyone else. The relative value of each artist to each person gives people the freedom to buy whatever tokens and however many tokens they want. Some people may not buy any tokens at all. Some people may buy an index of classic rock tokens or Italian disco tokens. Some people may spread their money across Taylor Swift, Beyonce, and Rihanna tokens. And some people might pour all their money into buying Kanye West tokens. Each of these decisions are some combination of a person’s love for the music and desire for responsible financial investments.

This is where things get interesting. That means that all artwork & relationships could be priced at an individual peer-to-peer level. Maybe Wu-Tang Tokens could have a sliding scale of benefits. People who own 100 tokens might get a 10% lifetime discount on all Wu-Tang Merchandise. People who own 1000 tokens might get ‘season tickets’ to all concert performances. People who own 10000 tokens might get exclusive access to a private Wu-Tang party. The relative value someone is willing to pay will give them incremental benefits from their musician heroes.

The already famous, already successful Wu-Tang Clan may easily sell millions of tokens around the world if they were to do an ICO. For a young country singer performing in small bars around Texas however, selling a few hundred of her tokens may be that ‘startup capital’ she needs to fund her career. Many musicians are left behind not because their music doesn’t have appeal, but because they are unable to secure the funding to market themselves. This situation also exists for other types of artists. Without access to the most exclusive galleries and art shows, you will have a tough time making it as an artist. In a world where you can finance artists directly through their tokens, supporting them as their part-patron/part-shareholder, you are improving the likelihood that even the most obscure artists can provide value to some individuals across the global market economy.

This is a new kind of direct relationship we can build between artists and fans, a new environment that can place a new layer of value for the artists in our society. We could more accurately value art and this would make even Martin Shkreli happy! As a self-proclaimed fan of The Wu-Tang Clan and hip hop in general, Shkreli could continue paying large sums of money to support his favourite hip hop artists through token purchases. If he owns Wu-Tang Tokens, he benefits from the increasing value of the Hip Hop group across all of their activities and not just by holding the one album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin.

Blockchain technology can be a truer measure of value for artwork and enable better compensation for artists. Ideally, if we have artwork of all types better valued, then society as a whole should be able to place a higher, more accurate value to artists. Right now, I believe that art is undervalued in terms of its contribution to society. While not every artist can be as big as The Wu-Tang Clan, there is a huge long tail of artists of all types who could benefit from a new way to monetise their creativity.

I believe that blockchain, when applied to the music industry, can restore and reinvigorate creativity by giving everyone in society an opportunity to be not only a patron, but a shareholder of the arts.

Congratulations @enfantterrible! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @enfantterrible! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit