Seated in front of the man that everyone feared, in 1809 a battle took place that would be unheard of for the time. Long before man dreamed of concepts like AI and machines threatened to change human life, an automaton confronted Napoleon Bonaparte himself in a game of chess. And the machine won the historic character. Just like he did with Benjamin Franklin. This was his incredible story.

It was called El Turco and it happened several centuries ago, in an era where the automatons were "fashionable". His story, his true story, is so fascinating that it was recorded for the annals of history. And it is that the Turk, as you can imagine, was not really El Turco.

Introducing the legend: the first automatons

At the beginning of the 1770s the name of a Hungarian inventor and writer, Wolfgang von Kempelen. The man was adviser of the court of Vienna, although also was recognized by his great gifts like excellent chess player. In fact, Kempelen himself boasted of playing often with the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa.

Kempelen was originally from Bratislava (formerly Kingdom of Hungary, now Slovakia). He was born into a noble Hungarian Catholic family whose father was an adviser to the Imperial Household. Kempele became famous with a number of earlier inventions, so when word got out that he had built an automaton that could win any human to chess, the news created great excitement.

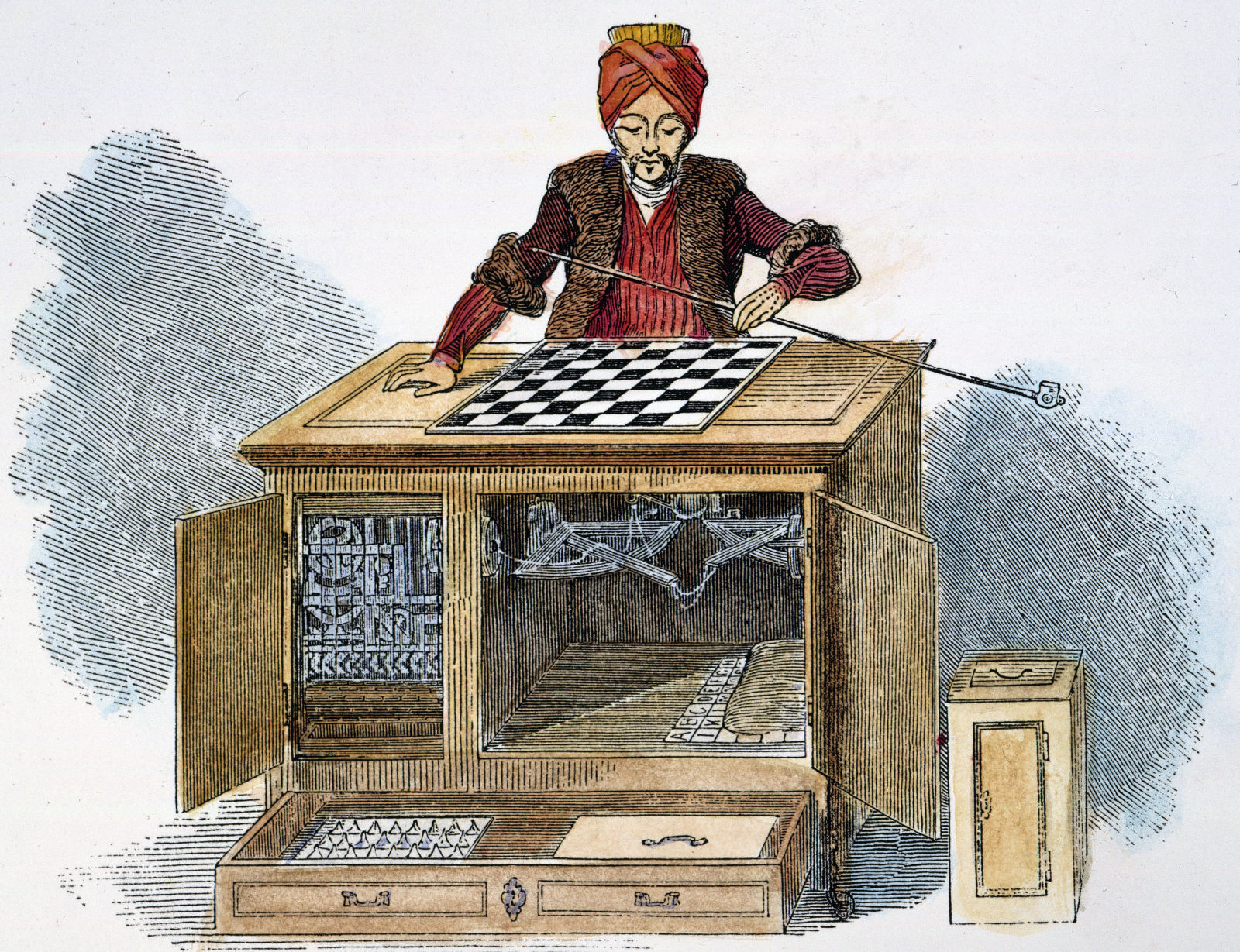

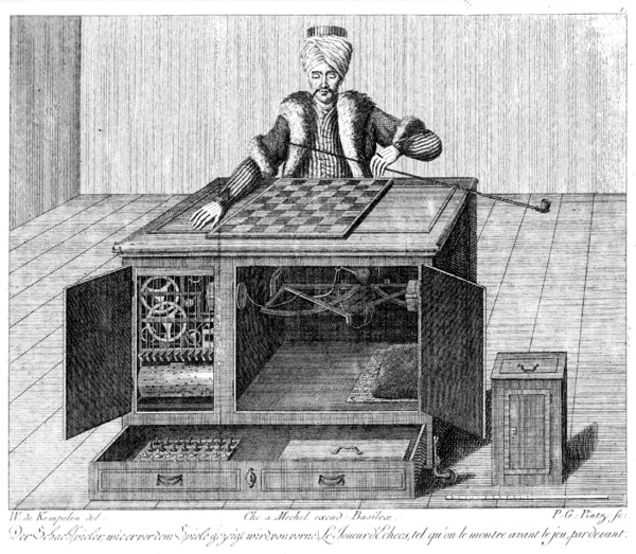

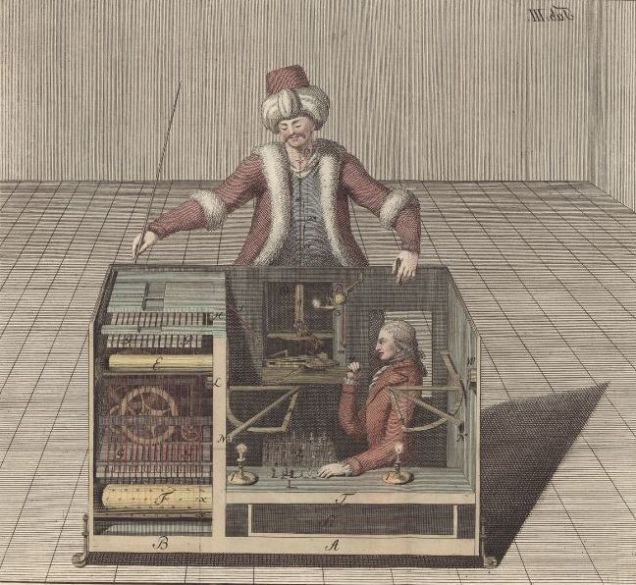

The Turkish longing took place in Vienna, at the court of Empress Maria Theresa. In an expectant room Von Kempelen began his demonstration of the functioning of the automaton. First by opening the doors and drawers of a small closet where you could see the light of a candle at the end. Inside it was a clockwork gear and machinery. Of course, it looked like a most complex machine. Kempelen then closed the closet, picked up a chess piece and moved it to another square.

The game began with the Turk shaking his head from side to side to inspect the board, so it seemed that he was deciding what his first move would be. Then he moved his left arm, extended his fingers, and picked up a chess piece to move it to another square.

The truth is that at that time what they were seeing in the royal hall was relatively standard. Automatons, machines that mimicked the figure and movements of an animated being (technological equivalents today to the concept of autonomous robots), had developed many centuries ago. Historically, the first automatons went back to prehistory, passing through classical Greece (statues with movement thanks to hydraulic energies), Middle Ages and, especially, in the eighteenth century, with the so-called epoch of splendor.

The main reason is due to advances in watchmaking. In addition it is added that the works acquire a scientific component where the obsession for trying to reproduce as closely as possible the movements (and behaviors) of living beings. Thus came characters like Jacques de Vaucanson, a magnificent watchmaker who also had knowledge of music, anatomy and mechanics. The result: his famous duck with digestive apparatus, more than 400 moving parts with which the automaton was able to beat the wings, eat, and most important, perform the digestion imitating in detail the behavior of the bird. Obviously it was a hoax and its mechanism did not "eat" the same as "defecaba", but the trick was really incredible and was the first great piece of automaton, the most accomplished.

After Vacanson came Friedrich von Knauss, the creator of one of the first automatons writers and without any doubt the shuttle for the work of the great Pierre Jaquet-Droz, possibly the best and best-known creator of automatons in history. Three would be his most famous works: The pianist, the draftsman and the writer, the last being the most difficult, composed of more than 6 thousand pieces and with the ability to write using a pen thanks to a wheel where the characters were selected one by one , so that small texts could be written at a rate of 40 words in length.

There were many more in the great century of the automata but the described ones are worth as perfect examples before the appearance of the Turk. The automata, both in the form of mechanical animals and humanoids of the most expressive, delighted royalty and commoners, and El Turco, by its repercussion, was to have a special place in history.

The Turkish against the world

Compared to many of the masterpieces described above, Kempelen's work, with a sort of turbaned mannequin sitting in front of a desk and with an expressionless face of carved wood and spasmodic movements at its extremities (arms), was a product lower. But the important thing in the piece was his ability to play chess. The turkish was good, very good. So much so that until that date it had never been thought that a machine could be able to "think" and win a human.

The Turk was not only an expert in performing a repetitive task, the automaton responded with skill to the unpredictable behavior of human beings. In other words, the incredible and unheard of part was that it seemed to be functioning autonomously, guided by its own sense of rationality (and reason). If the human opponent tried to deceive him, as the Napoleon himself did at the time, the Turk was able to scold and move the chess piece back to its original position. Not only that, in case the attempt to deceive was repeated, the Turk slipped his arm on the board, spreading the chips on the floor in disapproval.

Obviously behind the automaton was "trick", but the nature of the deception was so incredible that for decades no one knew how to decipher it. After that first demonstration in 1770, which surprised Maria Theresa and her assistants, Kempelen would leave the automaton for a while. It would not be until the death of Maria Teresa herself that she became aware of him. His son and successor to the throne, Emperor Joseph II, remembered the piece that had so excited his mother and asked for him to Kempelen.

Thus it was that from 1783 the man begins a tour with the Turco, a tour by recommendation of Jose II. In Paris it was a sensation and the spectators could not believe what they were seeing. Everyone who challenged the automaton to a game ended up losing. It was a time of great encounters, such as the historic game that faced the machine with Benjamin Franklin, who like Napoleon attempted an illegal move, to which our automaton was "angry" and responded by throwing the chess pieces.

The tour took Kempelen and Turco through England and Germany during the following year. That's when people began to speculate about the operation and nature of the machine. Some, like the British author Philip Thicknesse, got indignant at the idea that the Turkish was a purely mechanical creation whose game was free of human influence. The man went on to say that:

An automaton can move the chess pieces correctly as a result of the previous movement of a stranger is completely impossible.

Thicknesse, like many contemporaries, never thought Kempelen was directing him from afar through powerful magnets and strings or perhaps with a kind of remote control. Like other thinkers, he denied what he saw with a close approach to Ockham's razor (the simplest explanation is often the most likely) and therefore he thought that "there was probably a 10-year-old boy hiding under the machinery" ... to which it would be necessary to add that a gifted one for the chess.

The idea of Thicknesse, that of a young man hidden in the interior of the machine, was the one that reproduced more during those years. Sometimes the theory varied with the size of the minor or with the positioning of the same inside the automaton. But it is also true that all these theories were again rebuffed by Kempelen, opening once again the small closet and exposing the interior, with the drawers and the brightness of a candle in the background where the gear could be observed, thus demonstrating the impossibility of a human being in the interior.

His ability to win chess had to add two challenges Kempelen added on the tour. On one hand the automaton was able to solve the so-called Horse Problem. It was an old mathematical problem where it was requested that, having a board with X number of squares and a chess horse, and placing the latter in any random position, the horse had to go through all the squares at one time. The Turk would solve it at once with great ease.

The second challenge was the ability of the automaton to respond to the questions of the viewers through a board with letters. Incredible, especially considering that the machine could do it in several languages.

Years later, in 1804, the creator of the automaton dies. Kempelen died at the age of 70 and the Turk had several owners. This is a stage where the machine will go through several hands until you reach Johann Mäzel, a German mechanic and inventor who would keep the secret behind the Turk.

With Maezel came the famous game of chess (video above) that faced the automaton with the greatest of strategists on the battlefield, Napoleon Bonaparte. It happened in the year 1809, during the campaign of the battle of Wagram. Napoleon played with white and gave in to the skill of the machine, not before attempting some illegal move that the automaton reproached him.

The Turkish secret remained until its last days

Maezel took the machine on tour in the United States, another resounding success that would extend a decade. From the United States he traveled to Cuba, at which time Maezel's secretary dies and the tour is suddenly suspended. Was the secretary, a recognized master of chess, the man who drove the automaton? The truth is that after suspending the tour Maezel was lost on the map of the island. After a few months he was found dead inside his cabin back to the United States.

Nevertheless, the secret of the Turk remained until its last days. De Maezel happened to be property of a friend, this in turn finished selling it to finish in the Museum of Peale. On July 5, 1854, 85 years after its creation, the Turk was destroyed after a great fire.

Only then was the truth known. After the fire and after decades of astonishing the world, the son of the friend of Maezel who inherited it after his death ended up revealing the best kept secret. A publication in the chess magazine The Chess Monthly in 1857 put an end to the mystery.

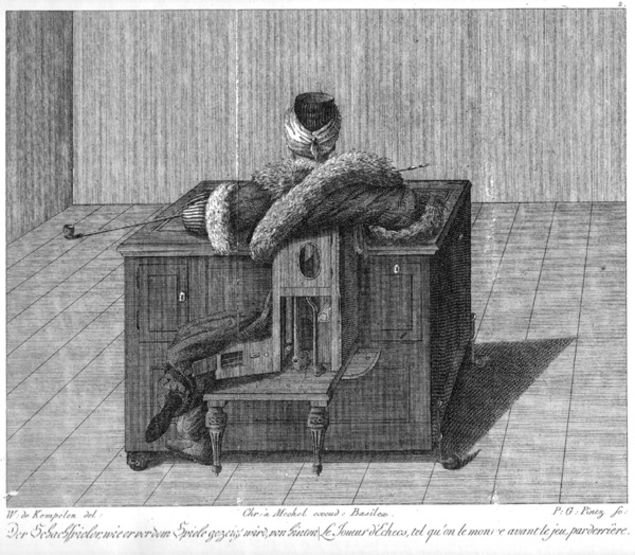

As you may have imagined, the truth was simpler than many of the lucubrations that were made. The Turkish was a mechanical illusion that worked through a covert operator, a person who controlled every move from a compartment inside the table. That person pulled the levers to "move" the arm of the automaton while keeping track of the plays. When Kempelen or one of the owners through which the automaton passed the front opened in the public eye, none of the drawers or compartments reached the rear. That hole that remained was precisely where a secondary chessboard was located that the operator used to follow the game. The bottom of the main board had a spring and each piece had a magnet, which allowed the operator to know which part had moved and where.

The fame of the automaton originated numerous replicas with the same trick or slight variations. Undoubtedly the best, if not the best, was The Chess player of the Spanish inventor Leonardo Torres Quevedo. The work of Quevedo is considered by many as the first computer game in history, but his story deserves a separate section.

As for the Turkish, although the machine was ultimately based on the behavior of a human (along with a little "magic" of the time), its mechanics so convincing was cause for wonder and concern. It was the first time in history that the man realized the implications that machines could have. At the dawn of the so-called First Industrial Revolution, the automaton raised questions as disturbing as the nature of automation or the possibility of creating machines capable of thinking.

Not only that, the Turk ended up posing the most disturbing and disturbing of the issues, one that we still do today without knowing the answer: the possibility of machines might be able to one day replace the human intellect.