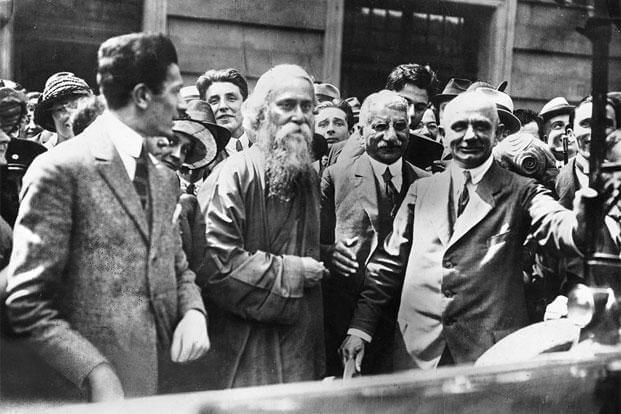

My Experience of the Swadeshi movement(by Rabindranath Tagore)

I seemed choked for breath in the hideous nightmare of our present time, meaningless in its pretty ambitions of poverty, and felt in me the struggle of my motherland for awakening in spiritual emancipation. Our endeavor after political ambition seemed to be unreal to the core, and pitifully feeble in their utter helplessness. I felt that it is a blessing of providence that begging should be an unprofitable profession and that only to him that hath shall be given. I said to

myself that we must seek for our own inheritance, and with it buy our true place in the world. I remembered the day, during the Swadeshi movement in Bengal, when a crowd of young students came to see me on the first floor of our Bichitra House. They said to me that if I order them to leave their schools and colleges they would instantly obey. I was emphatic in my refusal to do so, and they went away angry, doubting the sincerity of my love for my motherland.

In my paper called Swadeshi Samraj, written in 1905, I discussed at length the ways and means by which we could make the country of our birth more fully our own. whatever may have been the shortcoming of my words then uttered, I did not fail to lay emphasis on the truth that we must win our country, not from our own interia, our own indifference. Giving free vent to angry feeling is a species of self-indulgence. In those days there was practically nothing to stand in the spirit of the destructive level which spread all over the country. We went about picketing, burning, placing thrown in the path of those whose way was not ours, acknowledging no restraints, language and behaviour – all in the frenzy of our wrath.

Shortly after it was all over, a Japanese friend asked me, ‘How is it you people cannot carry on your work with calm and deep determination? This wasting of money can hardly be of assistance

to your objects. I had to reply,’When we have the gaining of the object clearly before our minds, we can be restrained, and concentrate our energies to serve it; but when it is case of

venting our anger, our excitement rises and rises till it drowns the object and then we are spendthrift to the point of bankruptcy’.

Then there was our greed. Inn history, all people have won valuable things by pursuing difficult paths. We had hit upon the device of getting them cheap, not even through the painful indignity of supplication with folded hands,

but by proudly conducting our beggary in threatening tones.

My experience in the West, where I have realized the immense power of money and of organised propaganda- working everywhere behind screens of camouflage, creating an atmosphere of distrust, timidity antipathy-has impressed me deeply with the truth that real freedom is of the mind and spirit; it can never come to us from the outside.

Therefore, I would urge my own countrymen to ask themselves if the freedom to which they aspire is of external conditions. Is it merely a transferable commodity?

Have they acquired a true love of freedom? Have they faith in it? Are they ready to make space in their society for the minds of their children grow up in the deal of human dignity, unhired by restrictions that are unjust and irrational.