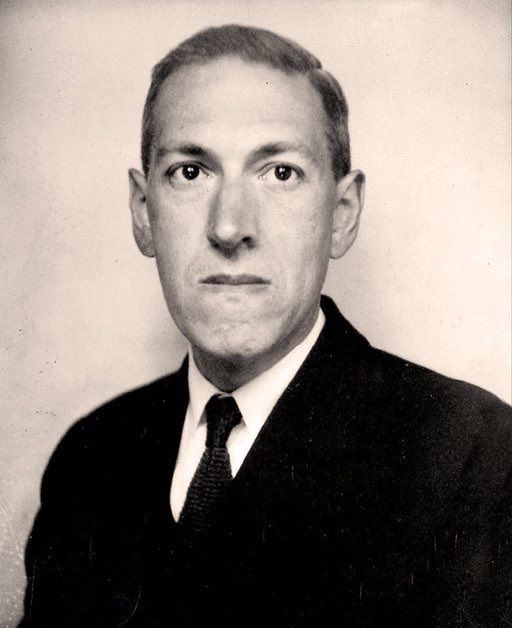

This blog post seeks to gain a clear understanding of H.P. Lovecraft's conception of cosmic horror. It is important to note that its scope goes only insofar as to my own understanding of Lovecraft's intentions, and the definition I have devised is not to be taken as a metaphysical definition ("the definition", as it were) of what 'cosmic horror' means. Linguistic monopoly is not the point here, only clarity of conceptualization and helpfulness.

I personally think this exercise is important because I believe terms like 'Orwellian', 'Kafkaesque', and 'Lovecraftian' are used in such liberal and ever-evolving ways that it obscures what the artist was originally aiming for, which is a shame (it literally is like the plethora of bad usages of the word 'literally', such as this very usage -- 'akin' is the better word here). So, let's make the best sense we can of what Lovecraft's actual conception of cosmic horror was. Maybe, just maybe, we can make a little effort in rescuing it from obfuscation, confusion, and (worst of all) debasement.

Before building our definition, I wish to resolve an apparent contradiction which might get in the way of our analysis, arising from what might be seen as opposing forces in the aesthetic creeds of what I will distinguish as the early and later Lovecraft. In H.P. Lovecraft's "Supernatural Horror in Literature" (1927), a lengthy dissertation on, and criticism of, supernatural horror literature (and literature which, though not necessarily designated 'supernatural horror' as such, nevertheless contains significant such elements), he makes clear what he considers to be the ideal aim of the genre (what he calls 'true weird fiction', which for our purposes has an identical meaning to 'cosmic horror'*):

"The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain—a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space."

Here it is is apparent that Lovecraft regards the supernatural as essential to achieving cosmic fear. Indeed, he later argues in the piece that practitioners of the supernatural horror tale are better equipped in achieving a sense of natural law being upended if they are materialists because "to [believers in the occult] the phantom world is so commonplace a reality that they tend to refer to it with less awe, remoteness, and impressiveness than do those who see in it an absolute and stupendous violation of the natural order."

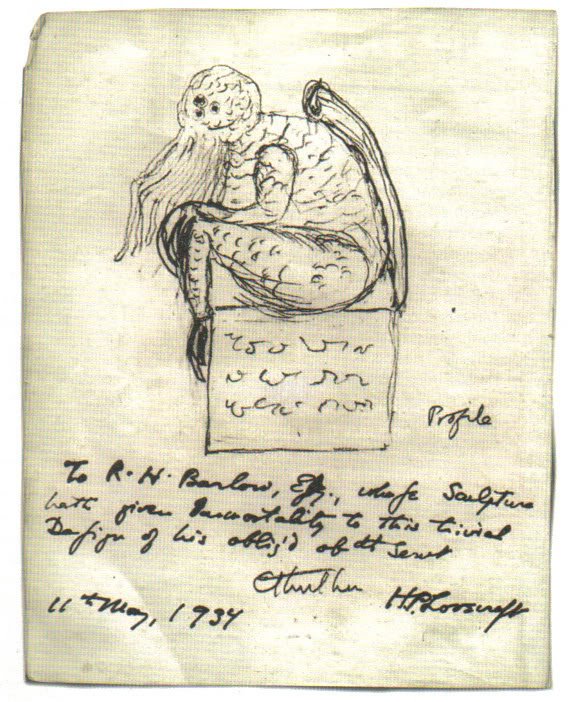

It wasn't until later, in 1931 (the same year that Lovecraft wrote his masterwork At the Mountains of Madness), that this conception explicitly changed. As he wrote to Frank Belknap:

"The time has come when the normal revolt against time, space, & matter must assume a form not overtly incompatible with what is known of reality—when it must be gratified by images forming supplements rather than contradictions of the visible & measurable universe. And what, if not a form of non-supernatural cosmic art, is to pacify this sense of revolt—as well as gratify the cognate sense of curiosity?"

We thus have an apparent contradiction between the early and later Lovecraft's attitude. After all, his earlier use of 'cosmic' in his essay (on supernatural horrror literature, no less) is one in which the conception of the supernatural is not only allowed, but essential ("there must be a hint... [of] a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature"), and the second ('non-supernatural cosmic art') in which it isn't. I hope to show the contradiction is negligible at worst, and that Lovecraft was arguably more concerned with rules and effects of aesthetics than precise ontology.

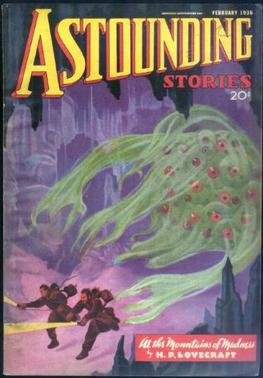

Before that, however, I would like to dispel the notion that the latter attitude is more dominant in Lovecraft's canon. Certainly the sensibility of a materialist/atheist/rationalist, as Lovecraft identified himself, is omnipresent in his work. However, as far as I'm aware, the first of Lovecraft's fiction in which he posits entities that are unambiguously naturalistic aliens (i.e. supplements rather than contradictions of the known cosmos) would be The Whisperer in Darkness, written in the latter part of his career in 1930. After that, only At the Mountains of Madness and The Shadow Out of Time have such unambiguously naturalistic alien beings as its antagonists. It appears then that those three, out of Lovecraft's entire canon, adhere aesthetically closest to the artistic creed he put forward in his letter to Belknap. The Shadow Over Innsmouth, The Colour Out of Space, The Picture in the House, Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family, Cool Air, and Herbert West -- Reanimator, though lacking in space aliens, are also all quite conceivably non-supernatural. Be that as it may, non-supernatural tales in Lovecraft's body of work are the exception to the rule (and still others might be classified as purely poetical and dreamlike). Of course, if we take Arthur C. Clarke's "third law" to be the true that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic", then perhaps all of the blasphemous entities that appear in Lovecraft's fiction are "really" space aliens, which -- though perhaps an appealing interpretation of the Lovecraft mythos -- would certainly be a post-hoc rationalization as a matter of teleological and historical fact.

So what do we make of this apparent contradiction? Here at least a couple of ways to look at it:

Lovecraft changed his mind about the essence of the supernatural's role in cosmic horror (that "there must be a hint... [of] a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space").

Lovecraft's view evolved to include within cosmic horror a subset of types, one including the supernatural and one dispensing with it.

Regardless, I think it's reasonable to deem that cosmic horror can be either supernatural or naturalistic. Certainly, even if both (1) and (2) are false, there's a sense in which Lovecraft at least held to both philosophies (supernatural vs. non-supernatural cosmic horror) at one point or another throughout his evolution as an artist (indeed, even after declaring his creed to Belknap, there were a few more tales he would write that were more conventionally supernaturalistic, such as The Dreams in the Witch House and The Thing on the Doorstep, though these could possibly be better explained by Lovecraft's doubting of the merits of non-supernatural cosmic horror after both At the Mountains of Madness and The Shadow Out of Time were rejected by Weird Tales).

Furthermore, the trivialness of this distinction, as I see it, perhaps lies in my intuition that Lovecraft was largely unconcerned with strict ontology in his mythos (which is almost a certainty, given how liberally he allowed his colleagues and friends to expand it) and more concerned with the aesthetics of narrative and effect, in which he sees that a Scooby Doo-like "explaining away" of cosmic events and entities harms the work, at least insofar as his aesthetic aim is concerned. Take, for instance, this excerpt from his essay that gives us an understanding of what cosmic horror is not:

"We may say, as a general thing, that a weird story whose intent is to teach or produce a social effect, or one in which the horrors are finally explained away by natural means, is not a genuine tale of cosmic fear..."

Also:

"Such writing, to be sure, has its place, as has the conventional or even whimsical or humorous ghost story where formalism or the author’s knowing wink removes the true sense of the morbidly unnatural; but these things are not the literature of cosmic fear in its purest sense. "

In, say, The Whisperer in Darkness and At the Mountains of Madness, the beings and events, though of wholly natural (or "supplemental") makeup, aren't "explained away" as such in a Scooby-Doo sense. The important point, as I see it, is that Lovecraft isn't so much concerned with whether the supernatural or natural are implicitly involved in conjuring cosmic fright, but that you don't explicitly explain them away, as it were, from fantastic to mundane occurrences. On this view, the whole issue of whether the entities and events occurring are of supernatural or natural origin is superfluous (surely daemons from unplumbed space are going to be upsetting, regardless of their metaphysical makeup) .

There's a quote often attributed to Lovecraft, though I could never track down the source, which goes, "Never explain anything." Whether or not Lovecraft said it himself is irrelevant for our purposes here. I use it as inspiration, with modification, to formulate the first part of our clear definition of "cosmic horror':

1. Nothing is explained away

The other point of what it's not helps us to formulate our conception further:

2. Didacticism is absent

Now that we know what it's definitely not, let's move onward to find out what it is. We would do well to look at what Lovecraft considered in his essay to be the all-important thing:

"Atmosphere is the all-important thing, for the final criterion of authenticity is not the dovetailing of a plot but the creation of a given sensation."

Indeed, one reason Lovecraft held Algernon Blackwood in such high esteem was because, "plot is everywhere negligible, and atmosphere reigns untrammeled."

We've already been given a very good idea for what this atmosphere consists in ("a certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present"), but Lovecraft gives it fuller form in this excerpt:

"The one test of the really weird is simply this—whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim. And of course, the more completely and unifiedly a story conveys this atmosphere, the better it is as a work of art in the given medium."

We can now, I believe, formulate the third part of our definition:

3. A profoundly dreadful atmosphere of impinging, unknown, outer forces

It may seem ambiguous at first when reading the essay as to whether or not he considers cosmic horror as a genre, a sub-genre, an aspect specifically of the horror literary genre, an aspect of literature in general, or an aspect of art in general. Certainly, though, the weight of preponderance goes to the last idea. Lovecraft criticizes many literary works in his essay, sometimes damnably so, but will always lavish praise if he thinks his aesthetic aim is ever achieved even in one page of a book he otherwise found to be repellent. As well, throughout his various other writings, he makes abundantly clear that cosmic horror is not found just in the realm of the literary, but in the architectural, visual, and musical arts as well. Therefore, we have what I believe is the last piece for us to formulate a full definition:

4. It is an aspect of art

I would like to end our definition here. To go onward, I believe, would be to confound Lovecraft's conception of cosmic horror with what is better labeled as 'Lovecraftian'. It might be said that Lovecraftian horror is, roughly, cosmic horror + an acute sense of the indifference of the cosmos at large (surprisingly, to me at least, neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for Lovecraft's conception of cosmic horror), visions of cyclopean vistas, antiquarian obsessions, tentacled and fish-like motifs, and even racism (and all that would have to be the subject of another blog post). As far as I'm aware of, Lovecraft never explicitly put forward any of that as part of an aesthetic aim in any theoretical sense (if I am wrong about this, or have overlooked something that contradicts that assertion, please bring it to my attention), and so I think it's appropriate to stop there.

And so, I present to you a clear definition of Lovecraft's conception of cosmic horror:

An aspect of art in which there is a profoundly dreadful atmosphere of impinging, unknown, outer forces, and in which didacticism is absent and nothing is explained away.

*A word on the phrase 'cosmic horror' itself. Throughout Lovecraft's letters and writings on his aim in the craft of horror fiction, he uses many words and phrases which are ultimately interchangeable. Ironically, 'cosmic horror' wasn't necessarily any more ubiquitous than the others, it just happens to have become the most ubiquitous one in our current parlance about his craft. Indeed, in his very long essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature", though the phrase 'cosmic horror' appears five times, it is never used in explicitly defining his aesthetic aim. Other phrases, such as, "cosmic fear", "the spectrally macabre" and "the really weird" are often used instead. This warning is to serve as a way to preempt purely semantic difficulties which may occur were one not aware of this.

The full text of "Supernatural Horror in Literature" can be found here: http://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/essays/shil.aspx

Belknap letter excerpt taken from S.T. Joshi's introduction in the Barnes and Noble edition of HP Lovecraft - The Complete Fiction

Congratulations @forrest-rice! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Excellent work.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit