Valve’s Gabe Newell on new games, brain-machine interfaces, and moving employees to New Zealand

In a couple of recent interviews with New Zealand’s 1 NEWS, Valve Software’s Gabe Newell has offered a few insights on what might be next for the Bellevue, Wash.-based gaming company and why he’s interested in brain-computer interfaces for gaming.

While Newell was typically careful to not say anything he couldn’t take back, this provided a rare possible look into the future for Valve, which traditionally does things on its own schedule and on its own time.

Newell has been in New Zealand for most of the last year, after a vacation in Auckland was disrupted by the country closing its borders due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Newell opted to shelter in place in New Zealand rather than rush back to the U.S., and since then has applied for residency. He occupied his time in-country with pursuits such as benefit concerts, teaching his travel companions how to play Valve’s DOTA2 computer game, and firing random bits of statuary into orbit.

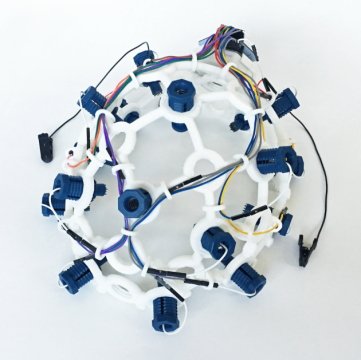

A new project at Valve has commanded most of Newell’s attention, involving the use of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) in gaming. The idea, as per Newell, is to work with OpenBCI headsets, an open-source project produced in Brooklyn, alongside virtual reality devices.

By reading a player’s body and brainwaves to determine their emotional state, a BCI interface could be used to customize an experience and improve immersion. One example is a game that can tell when the player is bored, and will react by tweaking its own difficulty. (This does feel like a natural progression from the notoriously sadistic AI “Director” mechanic in the Left 4 Dead games.)

“If you’re a software developer in 2022 who doesn’t have one of these in your test lab, you’re making a silly mistake,” Newell told 1 NEWS.

BCIs could be used to artificially suppress a user’s sense of vertigo, preventing players with motion sickness issues from being able to experience virtual reality. Valve’s work is also helping to contribute to projects that are developing synthetic body parts, since a video game engine can be used as an easily adjustable simulation for a company that’s working to make prosthetic limbs.

However, Valve is not going to branch out into the cyberlimb market any time soon, though Newell noted that the research projects give the company access to leaders in neuroscience.

The Valve boss also talked about his new temporary home and what it might mean for Valve’s future.

Last year, Newell had said that, despite widespread reports in the gaming press, there were no plans for Valve to decamp from Bellevue, Wash. to New Zealand. This year, however, there’s apparently some interest “at a grassroots level” at Valve to move some of its people overseas, primarily due to how well New Zealand has weathered the COVID-19 pandemic.

New Zealand is one of a handful of places in the world that’s mostly back to normal after last year’s lockdowns, thanks in part to its public health infrastructure.

As a result, there’s a strong chance that Valve may opt to move its esports tournaments, for games such as CounterStrike: Global Offensive and Defense of the Ancients 2, to New Zealand.

Both CS:GO and DOTA2 are considered some of the biggest games in the esports field, with DOTA2 boasting a comparatively massive $34.3 million prize pool for competitors in 2019, and both games are perennially among the highest earners on Steam, Valve’s online storefront. DOTA2‘s world championship, the International, is considered must-watch TV by much of the PC-gaming community, but the 2020 show in Stockholm had to be postponed to 2021 due to the pandemic.

Newell said Valve would be able to plan an in-person tournament for New Zealand.

“As long as COVID keeps mutating, it certainly is increasing the likelihood that we’ll be having events here,” he told 1 NEWS.

While neither Valve or Newell have committed to anything here, it would be a substantial shift to the status quo if New Zealand became a new international esports hub on the strength of its local health infrastructure. It wouldn’t take much for others to follow Valve’s lead.

Many of the biggest games in the field already operate on a global stage, with cities such as Shanghai, Vancouver, Seattle, Rio de Janeiro, Berlin, Krakow and Cologne having hosted esports finals in past years. With much of the international events community still reeling from the financial aftershocks of COVID, funneling most of the scene into the relative safe zones of New Zealand could provide some of the bigger organizations with a much-needed lifeline.

Newell also noted that the success of last year’s Half-Life: Alyx, a new VR entry in Valve’s landmark first-person shooter franchise, had “created a lot of momentum inside the company” to make and market more single-player games. He teased that there’ll be announcements on the subject soon; however, Newell also claimed to not know anything about “Citadel,” the rumored codename for a new Half-Life project that’s underway at Valve.

So, in closing: Valve may upend esports, publish new games, and work out a way to usefully hack the human brain in order to enhance that brain’s gameplay experience. Then again, it might not do any of that. The real takeaway here is that after a year in New Zealand, Gabe Newell is sounding more and more like a mad scientist.