Illustration of the two brain hemispheres, AI generated

Illustration of the two brain hemispheres, AI generated

Human history can be seen as a history of the de-lateralization of the brain. Evolutionary, cultural, and possibly metaphysical trends shaped human brains to increasingly become left-hemisphere dominant, bringing with it the increasing growth of civilization, monotheism, and science that we see today. As scientific evidence on the differences and roles of the two hemispheres grows, we see the parallels in human history. From the holistic, affective, and symbolic primitive cultures to our modern societies built upon objectivism, logic, and highly direct language.

While this is generally thought of as a history of human progress, this is ironically a materialistic, left-brained perspective. The modern world has enjoyed vast technological advancement and wealth creation, but it’s been hurt just as much — if not more — by these. The gaining of superior material conditions has led to a corresponding loss in human meaning and purpose. The growth in scientific, concrete knowledge has led to a change from traditional forms of knowledge such as the symbolic, mythological, and spiritual (however you wish to interpret that last one.) Rates of mental illness, nuclear proliferation, the climate crisis, and other dangers loom on the horizon. We would think that this era of supposed prosperity should’ve only improved worldly conditions, but we still face just as many crises as at any other time.

As far as culture goes, various developments in cultural beliefs, revolutions, and general consciousness shifts happened as well. Arabs, Chinese, and other cultures developed early scientific and industrial developments centuries ahead of the West. However, it seems that special circumstances made these accelerate in Europe specifically. The Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the Scientific Revolution were influenced by the increasing dominance of left-brained thinking that only achieved its full form in Europe. It’s no coincidence that scourges such as realism, nihilism, and fascism developed in the modern world. The West, and with increasing globalization in other areas, has dug itself into an entropic hole.

Japan and Korea perfectly exemplify this. If you know anything about these countries, you’d know that things aren’t going well for them. These two countries, which arguably accelerated these developments even faster than the West, are self-imploding. This might be the unfortunate fate of the West if it continues on the same trajectory. In fact, there are already early signs of this. Political polarization, below-replacement birth rates, and a mental health epidemic are not hopeful signs.

The only way the West and other cultures can prevent these crises is to incorporate tradition back into their cultures. This isn’t tradition in the modern sense of the world. It’s not an appeal to conservatism, where the only idea of tradition is going back in history. Rather, it’s a shift in perspective. Modern cultures should incorporate ancient Wisdom from peoples who had a more balanced mode of consciousness. They should reconnect with holistic, intuitive modes of thinking. Doing this will allow actual progress toward solving existential crises such as nihilism and climate change.

A Brief Overview of Religion

Rather than explaining the differences between right and left modes of thought in a scientific, scholastic way, I’ll try to drive the point home by framing this distinction from different perspectives. One of these is religion. The history of religion mirrors profound truths about the human mind. The study of religion shines a light on the consciousness states that lead to different types of religions arising in different cultures.

The most primitive of spiritual beliefs were beliefs of animism. Everything in the world had some spiritual essence that made them just as living as you or I. This belief in the agency of all things mirrors the (supposedly) primitive, right-brained, ‘schizophrenic-like state of human consciousness. At this time, humans interpreted the world akin to what the right hemisphere would interpret: they communicated in symbols rather than language, saw agency in everything, and made minimal categorizations.

As humans tend to do, they wondered about the world they lived in. And just like us moderns, they sought answers. Like every culture in the world, they eventually developed their own religion. The “primitive” religions of these right-brained individuals didn't see Deities as resembling human actors but as parts of nature that held deep spiritual power and value. Rivers, mountains, stars, and even the Sun were considered a type of Deity.

As humans evolved to become more left-brain dominant, these impersonal, natural deities transformed into personal, human deities. Eventually, these polytheistic cultures further ‘lateralized’ their religions into more objective, centralized deities. The Greek Gods became centered around the cult of Zeus, the Egyptians around Iris and Osiris, and the Judea around Yahweh and Yasherah. These distinctions between often masculine and feminine Gods were highly categorical and left-brained, but they retained some degree of subjectivity. Eventually, even that was stripped away. These religions further centralized into the patriarchal, monotheistic religions that we’re familiar with today. The immense success of Christianity — still the biggest religion in the world — shows how much this development took over humans.

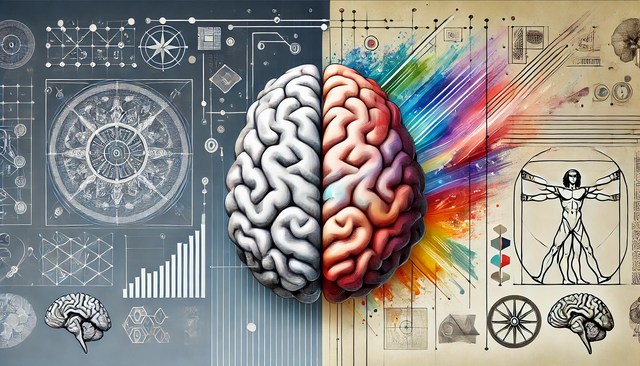

Yakob Oskanov/Shutterstock

Yakob Oskanov/Shutterstock

The Christian religion centered around objectivity, (left-brained) rationality, and logos is perhaps the best descriptor for the modern mode of thought. As secular as we think ourselves to be, logos still guides our rationality even into the scientific age. Our common and fundamental cognitive biases towards objectivity and rationality, apart from further highlighting the bias-prone left brain’s dominance on our thinking, cannot be meaningfully separated from the biases that shaped the founding of Christianity.

Nietzsche’s enlightening — yet problematic — distinction

The fact that we would consider their behavior to be primitive is very telling. It says a lot about our own conscious state. Nietzsche saw a glimpse of this duality of human consciousness in “The Birth of Tragedy.” Represented by the Greek Gods Dionysus and Apollo, he saw this as a metaphysical truth about human culture. Very tellingly, he developed this concept by studying Greek culture, which was well on its way to “Apollonian” consciousness. He called for a synthesis of these two forces, as represented by the Greek tragedies.

The very concept of Dionysian and Apollonian duality was biased in favor of Apollo from the start. However, it’s still a useful binary that only an enlightened person such as Nietzsche could have devised. While incomplete, it gives a good starting point for understanding the true dichotomy of left and right-brained human consciousness.

The Apollonian is represented by order, reason, and Summer. The Apollonian mode of thought emphasizes rationality, order, and structure. It works with binary distinctions of categorization: beauty/ugliness, true/false, good/evil. This makes it a fundamentally discriminating mode of thought — there is only one God, only one subjective truth, only a binary system. It has also traditionally been associated with the masculine and artificial. A person operating under the Apollonian is expected to be orderly, disciplined, and stoic (as far as our current misunderstanding of the term, anyway).

The Triumph of Aurora

The Triumph of Aurora

The Dionysian is represented by chaos, emotion, and passion. It emphasizes emotionality and instinct and does away with binary distinctions, categorization, and the idea of objectivity. It has been associated with the feminine and nature. A Dionysian person might be expected to be more emotional, passionate, and instinctual.

As might be clear from reading these descriptions, terms such as objectivity and rationality themselves carry emotional weight. Most of us react negatively to the idea of irrationality, subjectivity, and instinct. We tend to believe these qualities make us inferior in some way, or at least least developed. We also make the wrong conclusion that rationality is associated with the left, Apollonian.

This couldn’t be further from the truth. As shown by history, you’ll often find that left-brain-driven individuals can be greatly irrational. This is partly why native peoples are called primitive. Nietzsche’s binary distinction shines light on some fundamental concepts, but it still leaves us open to bias towards the Apollonian. A better conceptualization, then would entail a broader overview of left/right brained modes of consciousness.

Further Clarification on the Dichotomy

Naming this binary after the left and right brain hemispheres serves both an intuitive and a practical purpose. It is the most accessible and easy way for modern people to understand these concepts. Even referring to the dichotomy in an equivalent way, such as feminine/masculine, symbolic/literal, irrational/rational, and a number of other conceptualizations, would obscure its meaning. Putting in terms of masculine and feminine, for example, might evoke biases about gender politics. Our current world has been shaped by a materialistic, mechanistic view of the world — an Apollonian view. Since the world has shaped us, most people respond better to similar conceptualizations. We also respond better to presenting this as a binary, which is admittedly an incomplete conceptualization. A true understanding of these differences in consciousness would transcend the world of ideas, which makes it outside the scope of this post.

For our purposes, the brain is the best and most meaningful example of this. We tend to see humans as little machines that we haven’t yet managed to hack. We haven’t figured out how we work, but we eventually will, and we will use science to explain it. We can find people who extend this view of the world to their more philosophical and ontological beliefs; if our brain is the control center for our human machine, any changes in its material structure will cause changes in the way we experience the world. I must insist, though, that this Apollonian, hemispheric description is limited. It might be easy for us to understand, but it’s only to be understood as a useful simile, not as a literal description.

A Divided Brain?

Julian Jaynes’ Bicameral Mind Theory attempts to explain this shift. Jaynes noticed that native peoples seemed to differ significantly in the way they developed their inner dialogue. He argued that the idea of having an inner dialogue was something humans only developed very recently. He theorizes that humans did not experience communication between the two hemispheres until relatively recently.

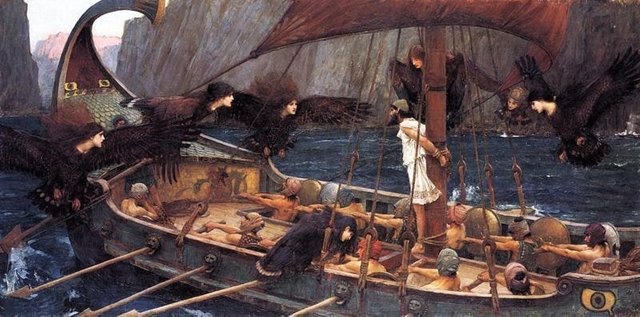

As often happens, the Ancient Greeks were the prominent example he used. He points to the way people spoke in classics such as the Odyssey. The characters in this epic poem never gave any indication that they themselves were thinking; they always presented their thoughts as commands from the Gods. Jaynes thinks that this is a convincing example of how humans did not use to have an “internal dialogue” where they felt their thoughts as their own. Instead, their thoughts would’ve came to them as auditory hallucinations, which would explain why the characters in the Odyssey were always being directed by Gods. He also used examples from the Old Testament, pointing out that there were no mentions of cognitive processes such as introspection and no indication that the writers had self-awareness.

Odysseus was a particularly interesting character in the Odyssey. The fact that he was the main character — our equivalent of that, anyway — was a very telling foreshadowing of the shift that might have already been happening. Odysseus was characterized by being a schemer; he used his wit to lie, manipulate, and generally get his way. These character traits would’ve been fairly rare in a society where most people were instinctual and not very much in tune, if at all, with conscious, deliberate thought. The deliberate scheming and planning Odysseus displayed requires intense left-brained activity; broadly speaking, it’s the hemisphere responsible for filtering out irrelevant information and hyper-focusing on a single task. This is what’s often called executive function. In this sense, Odysseus could be seen as the prototypical new human who had access to these meta-cognitive functions.

Odysseus and the Syrens, John William Waterhouse (1891)

Odysseus and the Syrens, John William Waterhouse (1891)

If the Bicameral Mind theory is correct, people would’ve been in a state of ego dissolution prior to the two hemispheres connecting. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the Odyssey was written before Siddhartha Gautama created Buddhism; by the time the Buddha embarked on his meditations, Asian cultures would’ve already developed a unicameral mind. Perhaps his creation was a necessary way for humanity to cope, just like the Judaic religions were in the West; perhaps they provided ways for people to cope with this relatively new mode of human consciousness that was bringing so much suffering. In this way, religion could serve as a medium for people to balance their asymmetrical modes of consciousness. This would explain why, regardless of how many problems one could find with it, it remains an essential institution for many humans — even in this secular age.

As the corpus callosum came to allow communication between these two, so did human self-awareness emerge— along with other things like hierarchical, logical thinking, and monotheism. Since functions associated with the left hemisphere were particularly useful for the purposes of warfare, state planning, and others, the left hemisphere started gaining more dominance.

This is where human cultures started seeing the early signs of the monotheistic shift to come. Their societies also started to shift increasingly towards being in opposition to nature rather than alongside it. With the holistic, non-judgmental, non-instrumentalist influence of the right brain fading, the instrumental desire for humans to subdue and control nature arose. Perhaps fundamental developments such as farming and statesmanship cyclically fed off of this: they arose with the newfound connection of the two hemispheres, and to maintain and perfect them, humans further evolved left lateralization.

A Lost Connection

We sometimes think of Native peoples as peaceful, nature-loving people. While this was true in practice, our perspectives are biased. Native cultures did not live in harmony with nature due to a moralistic realization that destroying it was wrong; it was their Modii Operandi. Some Native North American tribes, for example, had immensely sophisticated agricultural practices that science is only recently catching up with. The techniques these native peoples would use often showed great attunement to natural patterns and events. They developed these not through scientific reasoning about how to transform nature into their will, but due to their attunement to natural patterns and nature as a whole.

This attunement to nature was their connection to right-brained thought: holistic, pattern-seeking, and intuitive. This stands in sharp contrast to our own logical, detail-oriented, scientific tendencies. These differences are very unlikely to be caused merely by literal changes in the functioning of brain hemispheres, though evidence from human neurology does support this trend. Most modern people have a left-leaning asymmetry that is considered to be healthy. Yet this ‘healthy’ asymmetry might be a big factor differentiating British colonists from the Northern Native tribes. Culture also played a role, yet culture is shaped by human consciousness — and human consciousness is shaped by culture.

Discrimination — Hemisphere-Wise

The history of how moderns have treated brain asymmetry, or rather the outcomes stemming from it, helps us gain great insights into the cultural preferences modern cultures hold. The history of pathologizing people with decreased, and sometimes increased, asymmetry is full of examples. Most of these are examples pathologizing people with right-brained hemispheric dominance, which lead to the pathologizing of the left as a concept.

It is commonly known that left-handed people were personally discriminated against for a long time. They must have also felt indirectly discriminated against when they saw terms such as ‘being someone’s right hand’ so positively. Languages often refer to negative things as being left, such languages stemming from Latin referring to the left as ‘Siniestra’ (sinister). Siniestra also means being evil and unlucky. The origin of the left and right political dichotomy stemmed from the institutional belief that the side supporting the monarchy, the right side, was the good and virtuous side. Modern science also pathologizes asymmetry, as emerging research has been claiming low asymmetry leads to issues such as low IQ, schizophrenia, and more.

The big problem with this trend is that it ignores the importance of the right-brained mode of thought. Input from the right brain is essential for understanding the world on a holistic, intuitive level. Native American tribes often had superior agricultural techniques due to this, techniques that science has only recently caught up to. But they also lacked certain technologies, such as gunfire, which were invented in more technologically driven cultures.

The Need for a Synthesis

Clearly, there are strengths to both modes of thinking. Nietzsche was one of many people who proposed a synthesis between these two. Several other thinkers have called for this union of opposites, a term coined by psychoanalyst Carl Jung. Defining Carl Jung as merely a psychoanalyst is a disservice to his broader philosophical contributions, but this is a concession that has to be made under the current paradigm. Psychoanalysis as a discipline has been one of the only sciences (many people don’t call it a science, and they wouldn’t entirely be wrong to think this way) to propose a synthesis between these two forces. Compared to related fields such as behavioral sciences, psychoanalysis generally achieves a more balanced perspective.

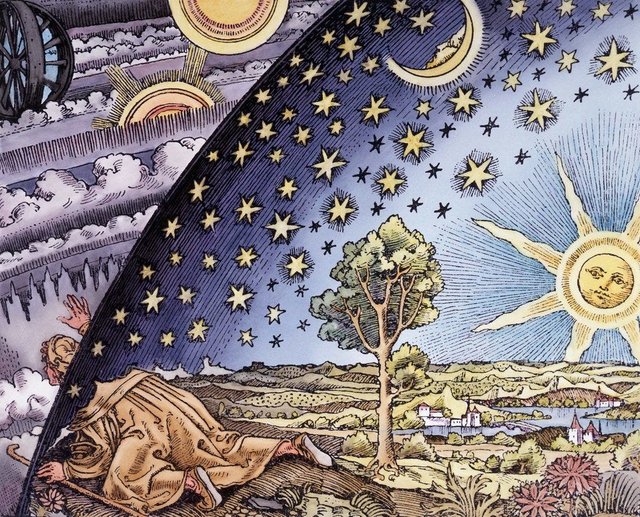

Flammarion Engraving, Unknown

Flammarion Engraving, Unknown

Even though psychoanalysis differentiates itself from other sciences, Carl Jung went further than even most psychoanalysis. A friend and intellectual friend of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung dived headfirst into the study of human consciousness. He generalized his studies of the unconscious far more than Freud, who was a visionary in his own right and proposed the idea of the collective unconscious. When talking about the collective unconscious and how humans universally shared in its archetypes, Carl Jung was unwittingly talking about an example of right-brained symbolic representations.

While he didn’t have access to science showing brain lateralization, he intuitively understood that humans have a connection to the right-brained mode of thinking, even if it was heavily repressed in his time and even more nowadays. An important reason Jung was able to make these connections was his wide breadth of knowledge. Rather than hyper-specializing in one field alone, as many left-heavy academics do nowadays, Jung studied various fields. He studied mythology and religion, drawing teachings from Eastern philosophy and Buddhism. He also studied native peoples and their cultures, comparing them to the ones in Europe.

Carl Jung’s idea of a union of opposites applies to various facets of a person’s character. Yet, you might often find that these distinctions tend to form across a left-right continuum. More important than his theories specifically, though, is the way he arrived at them; Carl Jung did not only use scientific methods, but he also allowed himself to be influenced by the wisdom of other cultures and disciplines. He also dove into his own psyche to develop his own theories, which are documented in the notable Red Book.

Jung’s studies are broadly misunderstood and sometimes mocked by people who call them unscientific — and that they are. These people are unable to see the intuitive connections he made during his interdisciplinary studies. Their fixation on science being the only method to arrive at truth shows a lack of perspective. It showcases a common failure of the left-brain: they miss the forest for the tree. While controversial, Jung was clearly one of the historically most attuned individuals to this human trend in consciousness.

Another theorist who proposed a similar idea was Jean Gebser with his idea of stages of consciousness. He proposed that human consciousness transitions across five non-hierarchical stages: magic, mythic, mental, and integral. It must be emphasized that these stages are non-hierarchical, meaning cultures in earlier stages are not necessarily inferior.

The magic and integral stages represent a transition from the magical stage of animistic cultures to the mental stage of our scientific culture. The integral — as its name implies — would be an integration of the first and last structures, which would also integrate the middle two. Gebser argued against the dangers of remaining in the mental stage without synthesizing it with the previous ones. He pointed to nihilism, nuclear proliferation, and social engineering as some of the horrors that might arise from continuing on the path we’re currently on. This also brings to mind the current climate change crisis that threatens to bring about global catastrophe. You could make even further connections to capitalism and to pathological materialism, but those would be outside the scope of this discussion.

Unfortunately, it might be impossible to understand many of these concepts by just reading about them. Learning in a logical, scholastic fashion doesn’t allow us to understand the world in its entirety. As shown by the issue of perception, one can describe every single detail of certain things, such as colors; we can describe objects with that color, describe the color as dark or light, and even use similes to try to describe it better. Yet, a hypothetical being who’s never seen that color doesn’t have true knowledge of it. They lack the lived experience of perceiving the color itself.

Perhaps a thought experiment doesn’t illustrate this point clearly enough. A better example most people are personally familiar with is sports. No matter how efficient, science-based, and effortful your study of a sport is, no amount of theoretical study will replace lived practice. Even for people who practice a sport, there is a significant difference between the practice and (so to speak) getting on the stage. Once it comes time to perform, the left-brain must be silenced. As Mike Tyson famously said about boxing: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face.”

This approach to learning things past a cerebral, academic level is an essential part of many religions and spiritual practices. There is not that big of a difference between world-class athletes and Buddhists. Buddhists don’t think they can merely reach Enlightenment by trying to “learn” about it. They acknowledge that there are limits to this form of thinking, with the Buddha famously pointing to attachment. The desire, passions, and emotions that stem from attachment were precisely what the Buddha used meditation to get away from. In this way, he and subsequent Buddhists used lived experience to gain a better understanding of the human condition.

The most influential spiritual and philosophical movement in the Western world — and many parts of the East as well — was Neoplatonism. Influenced by Monism, they believed that the human soul had a divine origin which had departed from its original state. Its original state would be a state of absolute knowledge of all reality, which Neoplatonists attempted to once again reach. They thought that this state could not be reached merely by logical and empirical observation, but also required one to achieve inner experience. This was felt rather than deduced, intuitive rather than logical, symbolic rather than literal. Like the monotheistic religions it influenced, the philosophy of Neoplatonism was holistic and integrative.

And it was definitely integrative: the Neoplatonist school had its own philosophy and academic tradition. Neoplatonists developed their own cosmology and teachings. They also used dialectical reasoning to develop their ideas. Plotinus famously didn’t want Neoplatonism to spread, as it would obscure the hierarchical instruction he had developed. A parallel to Neoplatonism could be found much later in Christianity. The Catholic Church, as a hierarchical and left-brained institution, eventually came to need a right-brained reformation. This came as Protestantism, which emphasized personal faith and lived experience rather than hierarchy and scholastics. This could be seen as the long-overdue, and unfortunately not yet integrated, Christian representation of Neoplatonist ideas.

The Scientific Approach to Brain Hemispheres

In “The Master and its Emissary”, psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist set out to explain the nature and impact of hemispheric differentiation. His ambitious work attempted to explain the “world of difference” between the left and right hemispheres. He also took this distinction and generalized it to the world as a whole: from philosophy, to culture, to the way the modern world is changing; hence the reason his work is described as ambitious.

He broadly defines the right hemisphere as the intuitive, aware, and holistic hemisphere. It is the patient and contemplative area that takes in all the information it can without applying judgment or hyper-fixating on the details. The right brain is defined as the master, with the left brain being its highly specialized emissary.

These brain assignments are one of the most controversial claims of his book. It inverts our notion that the left hemisphere is the ‘main’ one, the rational side of the brain that’s in control of its more dreamy and emotional counterpart. He backs this up through 20 years of research and observations. Throughout his academic research and his study of history, McGilchrist found that the right brain is often more correct than its counterpart. With its flexibility, patience, and ability for holistic interpretation, the right hemisphere generally achieves a superior grasp of reality. In fact, individuals with compromised left hemispheres were able to perform more tasks and have fewer difficulties in life than right-compromised ones.

The narrow, detail-oriented view of the left hemisphere explains why it’s often wrong. When tested, it’s more prone to cognitive biases, emotionality, and getting answers wrong. Even in tests of logic, which we would expect to excel at, the left brain can easily be tricked. When isolated, the left-brained is given the test: “All humans are monkeys, Socrates is a human, what is Socrates?” the left brain will always say the answer is correct. Even when it acknowledges the premise that “All humans are monkeys” isn’t correct, it is incapable of integrating the wrongful premise into the logical conclusion. This perfectly illustrates how the left brain is unable to gain the comprehensive, complete picture that its right brain master can.

Our conception of rationality as primarily left-brain robs us of perspective. The ancients, with their superior attunement to their right hemisphere, achieved wisdom that the left brain alone cannot achieve. The left mode of thinking is reductionist, instrumental, and detail-focused. This mode of thinking struggles with crucial aspects of human life, such as the pursuit of meaning, community, and creativity. This lack of the right brain’s perspective is not only shown by the Meaning Crisis but also by the most pressing issues arising from capitalism and individualism.

Commodification, alienation, and objectification are much too familiar of traits in the modern world. Robber barons, dictators, cult leaders, and other malicious actors are the end-point of a ruthless, instrumentalist left-dominated consciousness. People’s alienation from each other, and even from themselves at times, is also a result of the left’s dominance. Trends such as mindfulness meditation might be the much-needed answer to our collective call for help, but they’re difficult to truly partake in when we live in a culture that encourages and rewards its counterparts.

The German word Gestalt refers to something in its totality rather than just the sum of its parts. It’s our perception of something that only the right brain can truly get right. The famous example of Diogenes’ response to Plato illustrates this distinction. Plato defined a man as a “featherless biped”, showing a left-brained, descriptive definition of a man as only the sum of its parts. Diogenes found this so ridiculous that he brought a plucked chicken, exclaiming: “This is Plato’s man.”

Diogenes showed that Plato's left-brained logic was insufficient to describe something truly. For another example, consider a bird. We could define a bird as something with wings, feathers, and a beak. However, taking a plastic torso and putting all these parts in it doesn’t make it a bird. Similarly, a human is much more than its limbs, head, and organs. To attempt to describe one in terms of tissue, cells, and neurons is to miss the whole picture. As always, the left brain tends to miss the forest for the tree. The main challenge of the modern world is to reconnect itself to the right brain in order to see the Gestalts once again.