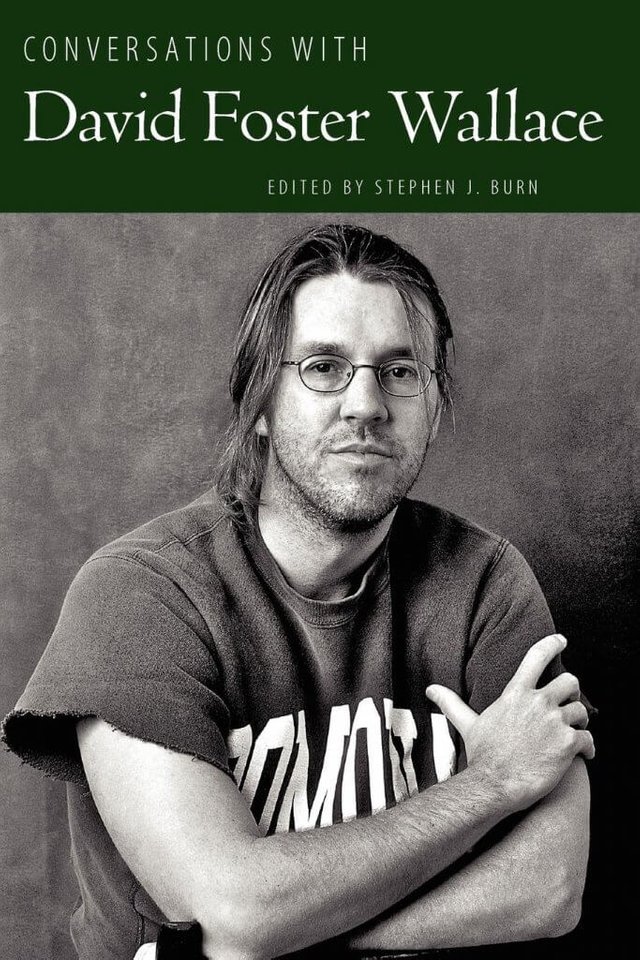

The following quotations are lifted from two different interviews that both are included in the brilliant Conversations with David Foster Wallace.

An Expanded Interview with David Foster Wallace Larry McCaffery/1993 From the Review of Contemporary Fiction, Summer 1993.

DFW: I think TV promulgates the idea that good art is just that art which makes people like and depend on the vehicle that brings them the art. This seems like a poisonous lesson for a would-be artist to grow up with. And one consequence is that if the artist is excessively dependent on simply being liked, so that her true end isn’t in the work but in a certain audience’s good opinion, she is going to develop a terrific hostility to that audience, simply because she has given all her power away to them. It’s the familiar love-hate syndrome of seduction: “I don’t really care what it is I say, I care only that you like it. But since your good opinion is the sole arbiter of my success and worth, you have tremendous power over me, and I fear you and hate you for it.” This dynamic isn’t exclusive to art. But I often think I can see it in myself and in other young writers, this desperate desire to please coupled with a kind of hostility to the reader.

LM: In your own case, how does this hostility manifest itself?

DFW: Oh, not always, but sometimes in the form of sentences that are syntactically not incorrect but still a real bitch to read. Or bludgeoning the reader with data. Or devoting a lot of energy to creating expectations and then taking pleasure in disappointing them. You can see this clearly in something like Ellis’s American Psycho: it panders shamelessly to the audience’s sadism for a while, but by the end it’s clear that the sadism’s real object is the reader herself.

LM: But at least in the case of American Psycho I felt there was something more than just this desire to inflict pain—or that Ellis was being cruel the way you said serious artists need to be willing to be.

DFW: You’re just displaying the sort of cynicism that lets readers be manipulated by bad writing. I think it’s a kind of black cynicism about today’s world that Ellis and certain others depend on for their readership. Look, if the contemporary condition is hopelessly shitty, insipid, materialistic, emotionally retarded, sadomasochistic and stupid, then I (or any writer) can get away with slapping together stories with characters who are stupid, vapid, emotionally retarded, which is easy, because these sorts of characters require no development. With descriptions that are simply lists of brand-name consumer products. Where stupid people say insipid stuff to each other.

If what’s always distinguished bad writing—flat characters, a narrative world that’s clichéd and not recognizably human, etc.—is also a description of today’s world, then bad writing becomes an ingenious mimesis of a bad world. If readers simply believe the world is stupid and shallow and mean, then Ellis can write a mean shallow stupid novel that becomes a mordant deadpan commentary on the badness of everything.

Look man, we’d probably most of us agree that these are dark times, and stupid ones, but do we need fiction that does nothing but dramatize how dark and stupid everything is? In dark times, the definition of good art would seem to be art that locates and applies CPR to those elements of what’s human and magical that still live and glow despite the times’ darkness. Really good fiction could have as dark a worldview as it wished, but it’d find a way both to depict this dark world and to illuminate the possibilities for being alive and human in it. You can defend Psycho as being a sort of performative digest of late-eighties social problems, but it’s no more than that.

Looking for a Garde of Which to Be Avant: An Interview with David Foster Wallace Hugh Kennedy and Geoffrey Polk/1993 From Whiskey Island, Spring 1993.

But there are a few books I have read that I’ve never been the same after, and I think all good writing somehow addresses the concern of and acts as an anodyne against loneliness. We’re all terribly, terribly lonely. And there’s a way, at least in prose fiction, that can allow you to be intimate with the world and with a mind and with characters that you just can’t be in the real world. I don’t know what you’re thinking. I don’t know that much about you as I don’t know that much about my parents or my lover or my sister, but a piece of fiction that’s really true allows you to be intimate with … I don’t want to say people, but it allows you to be intimate with a world that resembles our own in enough emotional particulars so that the way different things must feel is carried out with us into the real world. I think what I would like my stuff to do is make people less lonely. Or really to affect people. I think sometimes what I’m doing, if I try to be particularly offensive or outrageous or whatever, is just being really hungry for some kind of effect. I think you can see Bret Ellis doing that in American Psycho. You can’t make sure that everybody’s going to like you, but damn it, if you’ve got some skill you can make sure that people don’t ignore you. A lot of writers hunger to have their work out there more and to have good book sales, which I used to think was crass materialism, that they wanted the money, but it turns out that what you want is to have some sort of effect. Maybe you’ve snapped to this already. It took me years to figure that out.

Posted from my blog with SteemPress : https://niklasblog.com/?p=23088