Have you ever heard about the U.S. Army’s camel corps experiment at Camp Verde?

How well did the experiment work and how about those wild Ghost Stories cited in various state newspapers and in the Smithsonian?

From the book by Vince Hawkins

My mother in law Lois took us there when we went to visit them in the Hill Country of Texas!

Beautiful and unforgetable!

Years later, though we wished for them to live in our town so our family could have them for birthdays and holidays, we went to see them in two different facilities they were placed in.

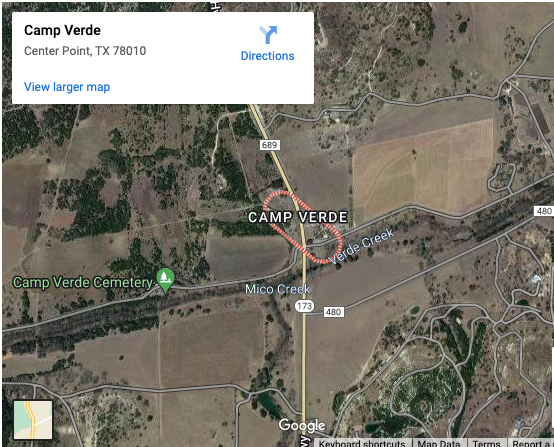

Camp Verde is an unincorporated community in Kerr County, Texas, United States. The town is approximately the halfway point between Bandera and Kerrville along SH 173 in the Texas Hill Country.

We were then able to take them to visit this neat landmark with an incredible history and beauty of it's own!

Upon one visit in 2022, we were viewing the gardens and one of the gardeners overheard me talking about their flowering hibiscus plants. He came over and was a wealth of info concerning how to get more flowers rather than an abundance of leaves as one I had grown from a tiny plant was full and lush, but very few flowers.

He said, he let those there at Camp Verde fully dry out, then water the pi$$ of of them!

We laughed and I said I would definitely give it a try.

Guess what, it WORKED!

To this day I follow his advice and have since added a new baby hibiscus that produces flowers in a lovely pink shade.

The first produces flowers in a red shade and I get so many at times that I dry them to make Hibiscus tea for my family!

Thanks to Lois and Bill for introducing us to Camp Verde!

Following is a little history and don't miss below where I show you the wild and what some deem as "weird" records from Camp Verde's operations!

Found in an unincorporated community in Kerr County, Texas, United States. The town is approximately the halfway point between Bandera and Kerrville along SH 173 in the Texas Hill Country.

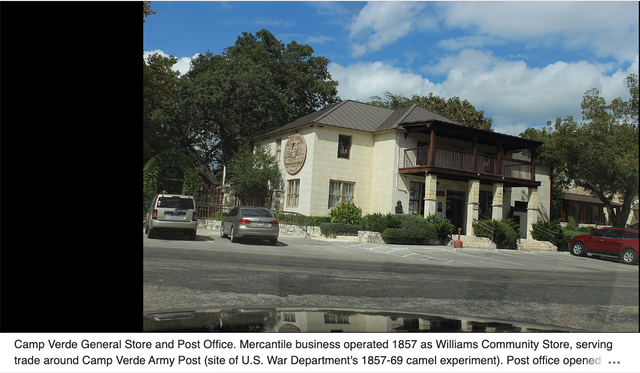

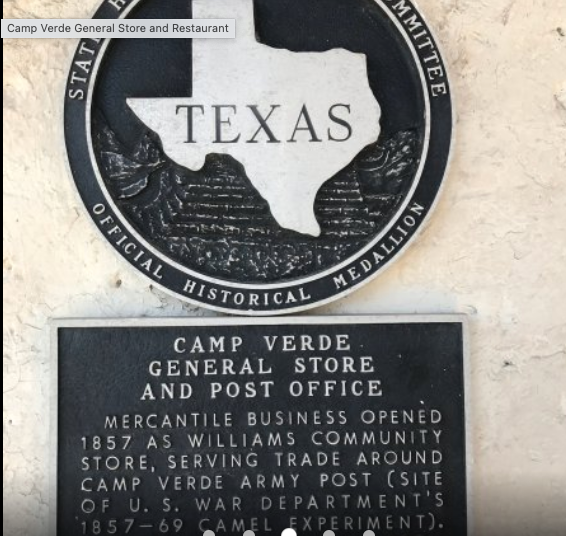

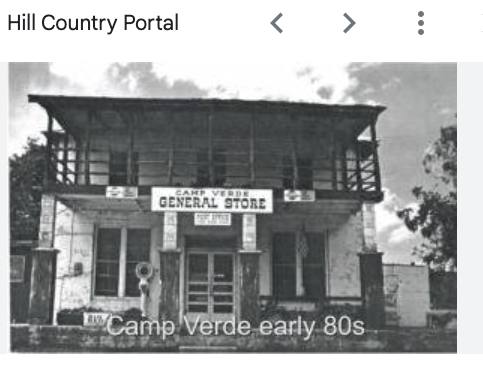

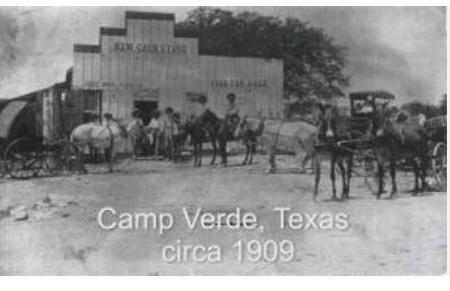

The town of Camp Verde came about from the Old Camp Verde military camp. The town grew around the old Williams community store (opened in 1857), which was built to serve the soldiers stationed at the base. After Williams died in 1858, German immigrant Charles Schreiner acquired the store. After the camp was abandoned, the store continued to operate as a post office for area residents.

The first post office opened in 1858, running out of Schreiner's store. This post office closed in 1866. When the post office reopened in 1887, Charles C. Kelly served as post master. However, this post office was also closed in 1892. Walter S. Nowlin re-established the post office and store in 1899.

What was the Camel Experiment?

Before the dawn of the American Civil War,

It was in 1854, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis [later became the president of the Confederacy), pushed for the use of camels by the American Army].

This initiative was passed by Congress on March 3, 1855, and the first camels arrived in the area in April 1856. After the fort was deactivated in 1869, the experiment died with it.

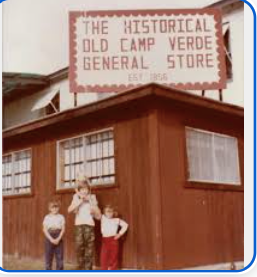

The Camp Verde General Store is still in operation to this day, having been in operation for over 150 years.

The store has become a fun place to visit and a bit of a tourist attraction in the area.

The store also runs the post office and operates a restaurant.

The next time I'm there I'll get more photos of the interior.

Hoping to visit again with Lois and Bill!

The Wild Camel West? You decide!**

As posted in a Houston article. . .

Ladies and gents of the Lone Star State, gather ‘round as we recount the brief and bizarre tale of the U.S. Army’s strangest division: the camel corps.

Yes, you read that right. The camel corps. Once upon a time in Texas, an army-sanctioned herd of camels roamed the Hill Country.

In the 1830s, America’s westward expansion was being curtailed by the inhospitable terrain of the Southwest, where vast deserts, scorching heat and towering mountain ranges were proving an almost insurmountable obstacle to people and pack animals alike.

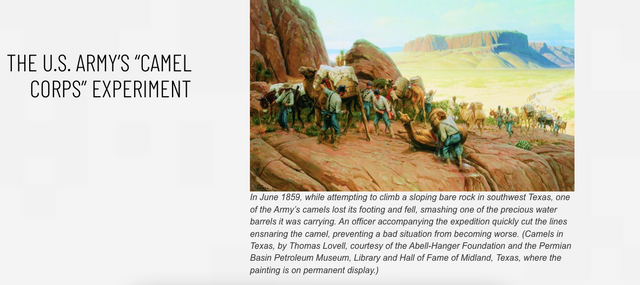

In 1836, U.S. Army Lt. George H. Crosman and his friend devised an unusual solution to the problem at hand: Camels. Vince Hawkins wrote in a scholarly article titled, “The U.S. Army’s ‘Camel Corps’ Experiment,” that the pair were so taken with their idea, they penned a report and sent it to the United States Department of War, which disregarded it.

“For strength in carrying burdens, for patient endurance of labor, and privation of food, water (and) rest, and in some respects speed also, the camel and dromedary (as the Arabian camel is called) are unrivaled among animals,” the report reads. “The ordinary loads for camels are from 700 to 900 pounds each, and with these they can travel from 30 to 40 miles a day, for many days in succession. They will go without water, and with but little food, for six or eight days, or it is said even longer. Their feet are alike well suited for traversing grassy or sandy plains, or rough, rocky hills and paths, and they require no shoeing…”

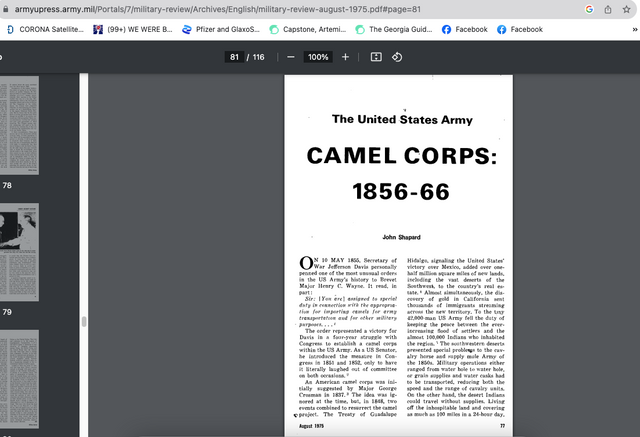

The dromedary idea remained dormant until 1847 when Jefferson Davis, then a Mississippi Senator, learned of it. [dromedary, also known as the dromedary camel, Arabian camel, or one-humped camel, is a large even-toed ungulate] He was so taken with the camel concept he proposed it to Congress in 1851 and 1852. Apparently, the proposal was “literally laughed out of committee on both occasions,” John Shapard wrote in a 1975 article published in the Military Review.

When Davis was appointed Secretary of War several years later in 1853, he again presented the idea to Congress. In an annual report in 1854, Davis told Congress, “I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of camels and dromedaries for military and other purposes, and for reasons set forth in my last annual report, recommend that an appropriation be made to introduce a small number of the several varieties of this animal, to test their adaptation to our country…”

And in 1855, at long last, Davis secured a $30,000 appropriation for the acquisition of a small camel herd.

To Brevet Major Henry C. Wayne, Davis penned what Shapard described as “one of the most unusual orders in the US Army’s history.”

“Sir: (You are) assigned to special duty in connection with the appropriation for importing camels for Army transportation and for other military purposes,” Davis wrote.

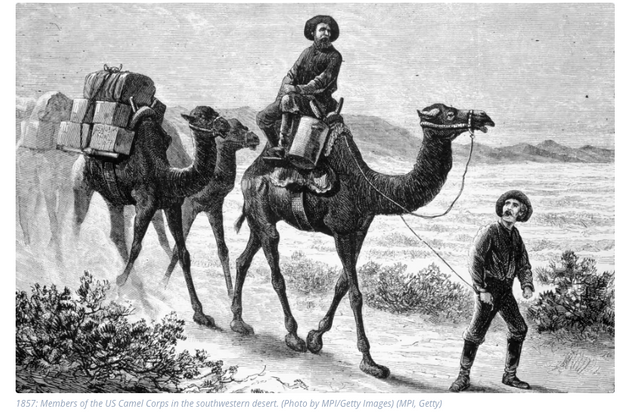

In a joint Army-Navy operation led by Wayne and naval officer David Dixon Porter, 33 camels were purchased in Turkey and Egypt and transported to the United States. Upon their return to the states, Porter was ordered back to the Mediterranean to procure even more camels. Six months later, he came back with 41 more.

In all, the camel corps was 75 animals strong and its home base was ultimately established at Camp Verde, Texas, 60 miles north of San Antonio.

There, Wayne tested the military usefulness of the camels. In one exercise, he pitted three wagons, each equipped with a six-mule team, against six camels. The parties were tasked with retrieving a supply of oats from San Antonio. In a report to Davis, Wayne said the camels won easily.

“From this trial it will be seen that the six camels transported over the same ground and distance, the weight of two six mule wagons, and gained on them 42 1/2 hours in time,” Wayne wrote.

In another test, a camel caravan traveled through the under-explored Big Bend. Though the soldiers nearly died of dehydration, the camels did remarkably well, the National Park Service wrote of the journey.

With these promising results, a much more extensive experiment was ultimately proposed and undertaken in 1857-- an expedition to Fort Defiance, New Mexico, and then on to Fort Tejon, California. When the journey began, the camels moved more slowly than the horses and mules and were often late reaching camp. However, by the second week of the journey they were outperforming the other pack animals. The camels’ slow start was later attributed “to their months of idleness and ease at Camp Verde,” Hawkins wrote.

When the caravan came to the Colorado River, officers were concerned the camels could not swim. They were pleasantly surprised when the largest camel plunged right into the water and swam across without difficulty. The remaining camels also crossed without incident, but several horses and mules drowned while attempting to navigate the water, Hawkins wrote.

Four months and 1,200 miles later, the group reached Fort Tejon in California.

Fast forward to 1861, and many of the camels became Confederate property when Camp Verde was captured during the Civil War.

During this period of turmoil, the camel herd was widely scattered. Some were returned to Camp Verde; some were used to pack cotton bales to Brownsville; some left in California escaped into the dessert; and one “found its way to the infantry command of Confederate Army Capt. Sterling Price, who used it throughout the war to carry the whole company’s baggage,” the “Handbook of Texas” reads.

With its attention focused on reconstruction, the U.S. Army sold the remaining camels at auction in 1866.

Though the fort at Camp Verde was deactivated in 1869 the general store remains open. Fittingly, many camel-adorned products are on offer there.

Another account in the Smithsonian reads as follows,

In the 1880s, a wild menace haunted the Arizona territory. It was known as the Red Ghost, and its legend grew as it roamed the high country. It trampled a woman to death in 1883. It was rumored to stand 30 feet tall. A cowboy once tried to rope the Ghost, but it turned and charged his mount, nearly killing them both. One man chased it, then claimed it disappeared right before his eyes. Another swore it devoured a grizzly bear.

"The eyewitnesses said it was a devilish looking creature strapped on the back of some strange-looking beast," Marshall Trimble, Arizona's official state historian, tells me.

Months after the first attacks, a group of miners spotted the Ghost along the Verde River. As Trimble explained in Arizoniana, his book about folk tales of the Old West, they took aim at the creature. When it fled their gunfire, something shook loose and landed on the ground. The miners approached the spot where it fell. They saw a human skull lying in the dirt, bits of skin and hair still stuck to bone.

Several years later, a rancher near Eagle Creek spotted a feral, red-haired camel grazing in his tomato patch. The man grabbed his rifle, then shot and killed the animal. The Ghost’s reign of terror was over.

News spread back to the East Coast, where the New York Sun published a colorful report about the Red Ghost's demise: "When the rancher went out to examine the dead beast, he found strips of rawhide wound and twisted all over his back, his shoulders, and even under his tail." Something, or someone, was once lashed onto the camel.

The legend of the Red Ghost is rich with embellishments, the macabre flourishes and imaginative twists needed for any great campfire story. Look closer, though, past the legend — past the skull and the rawhide and the "eyewitness" accounts — and you'll discover a bizarre chapter of American frontier history. In the late 19th century, wild camels really did roam the West. How they got there, and where they came from, is a story nearly as strange as fiction.

The camels were stationed in Camp Verde, in central Texas, where the Army used them as beasts of burden on short supply trips to San Antonio.

If the mule lobby didn’t kill off the experiment, the Civil War did. At the dawn of the war, after Texas seceded from the Union, Confederate forces seized Camp Verde and its camels. "They were turned loose to graze and some wandered away," Popular Science reported in 1909. "Three of them were caught in Arkansas by Union forces, and in 1863 they were sold in Iowa at auction. Others found their way into Mexico. A few were used by the Confederate Post Office Department." One camel was reportedly pushed off a cliff by Confederate soldiers. Another, nicknamed Old Douglas, became the property of the 43rd Mississippi Infantry, was reportedly shot and killed during the siege of Vicksburg, then buried nearby.

By late 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, the camel experiment was essentially finished. The California camels, moved from Fort Tejon to Los Angeles, had foundered without work for more than a year. In September, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered the animals be put up for auction. An entrepreneur of the frontier named Samuel McLaughlin bought the entire herd in February 1864, then shipped several camels out to Nevada to haul salt and mining supplies in Virginia City. (McLaughlin raised money for the trip by organizing a camel race in Sacramento. A crowd of 1,000 people reportedly turned up to watch the spectacle.) According to Gray's account, the animals that remained in California were sold to zoos, circuses, and even back to Beale himself. "For years one might have seen Beale working camels about his ranch and making pleasure trips with them, accompanied by his family."

The Texas herd was auctioned off shortly thereafter, in 1866, to a lawyer named Ethel Coopwood. For three years, Coopwood used the camels to ship supplies between Laredo, Texas, and Mexico City — and that's when the trail starts to go cold.

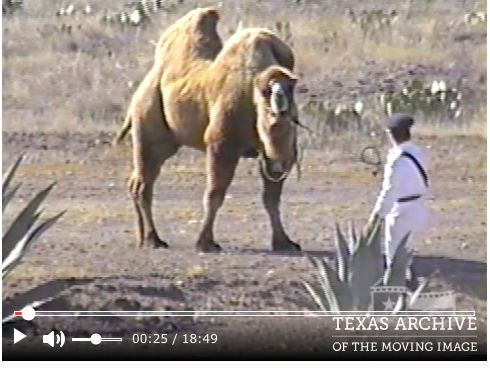

Coopwood and McLaughlin sold off their herds in small bunches: to traveling zoos, to frontier businessmen, and on and on. I spoke with Doug Baum, a former zookeeper and owner of Texas Camel Corps, to learn where they went from there. As it turns out, the answers aren't so clear. When the Army brought its camels to Texas, private businesses imported hundreds more through Mobile, Galveston, and San Francisco, anticipating a robust market out West.

"Those commercially imported camels start to mix with the formerly Army camels in the 1870s," says Baum. The mixed herds made it increasingly difficult to track the offspring of the Army camels. "Unfortunately, it's really murky where they end up and what their ultimate dispositions were, because of those nebulous traveling menageries and circuses," he says.

Report this ad

That's not to say the fate of every Army camel was unknown. We know what happened to at least one: a white-haired camel named Said. He was Beale's prized riding camel during the expedition west, and at Fort Tejon, he was killed by a younger, larger camel in his herd. A soldier, who also served as a veterinarian, arranged to ship Said's body across the country to Washington, where it could be preserved by the Smithsonian Institution. The bones of that camel are still in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History.

And as for the rest? Many were put to use in Nevada mining towns, the unluckiest were sold to butchers and meat markets, and some were driven to Arizona to aid with the construction of a transcontinental railroad. When that railroad opened, though, it quickly sunk any remaining prospects for camel-based freight in the southwest. Owners who didn't sell their herds to travelling entertainers or zoos reportedly turned them loose on the desert — which, finally, brings the story back to the Red Ghost.

Feral camels did survive in the desert, although there almost certainly weren't enough living in the wild to support a thriving population. Sightings, while uncommon, were reported throughout the region up until the early 20th century. "It was rare, but because it was rare, it was notable," Baum says. "It would make the news." A young Douglas MacArthur, living in New Mexico in 1885, heard about a wild camel wandering near Fort Selden. A pair of camels were spotted south of the border in 1887. Baum estimates there were "six to ten" actual sightings in the postbellum period, up to 1890 or so. The legend of the Red Ghost — a crazed, wild monster roaming the Arizona desert — fit snugly within the shadow of the camel experiment.

"Do I think it happened? Yes," Baum says. "And it very likely could've been one of the Army camels since it was an Arabian camel." In other words, the fundamental details behind the legend might contain some truth. A wild camel, possibly an Army camel that escaped from Camp Verde, was spotted in Arizona during the mid-1880s. A rancher did kill that camel after spying it in his garden. And when that rancher examined the animal's body, he found deep scars dug across its back and body.

Fact or fiction, the story of the Red Ghost still leads back to the inevitable, the unanswerable: Could a person really have been lashed onto a wild camel? Who was he? And if he did exist, why did he suffer such a cruel fate? Says Trimble, "There's just all kinds of possibilities."

More information found in books like these and online,

The above found in armyupress.army.mil

portal and link found in sources below!

Camels at Fort Davis from the National Park Service access government source below.

See Camels from the Handbook of Texas source provided below.

As cited in Texas Highways,

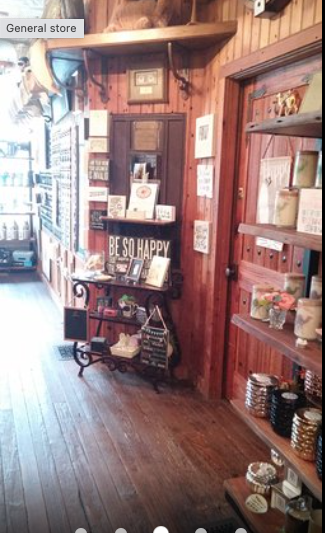

The present-day store’s stone edifice “was constructed after a flood swept away the original building around 1900,” according to the store’s online history. It has display cases, uneven wooden plank floors, and tin ceilings from that era. Outside, a 10-foot-high iron sculpture of a camel evokes Camp Verde’s history, as does the store’s logo. The sculpture was commissioned to commemorate the 150th anniversary and reenactment in 2007 of the first shipment of camels from Egypt to the Texas Gulf Coast. Live camels recently have been part of annual Christmas events at Camp Verde Store as well.

If you order dessert in the restaurant, a miniature chocolate camel adorns a slice of banana cream pie or the “apple basket” with ice cream, a favorite of friends Candy and Mike Stewart from Kerrville who treated me and my spouse to our Camp Verde lunch this spring. Some of Candy’s German ancestors are buried close by on a small ranch cemetery. Though she grew up in Houston, her visits to the Camp Verde General Store go back almost four decades—long before the 82-seat dining room opened.

Back then, she remembers, “a traveler could stop in the store for a sweet tea, Dr Pepper, Barq’s, button candies, licorice ropes, or a bag of Lays and make the kids happy.”

From Texas Co-op Power,

Caravans of drivers, bikers, cyclists and hikers daily trek through Camp Verde, midway between Bandera and Kerrville at the junction of State Highway 173 and Ranch Road 480. Those who pause at the Camp Verde General Store & Post Office treat themselves to an oasis-like experience—relaxation, good food and trade in the form of a gift shop filled with art, candles, jewelry, candy, lotions, kitchen gadgets, dishes, casual footwear, souvenirs and made-in-Texas jams, jellies and salsas, to name a few.

Each December, camels play key supporting roles with sheep, shepherds and wise men in Nativity scenes telling the Christmas story, but the image of a camel gets top billing on innumerable Camp Verde shopping bags that leave the store filled with holiday gifts. Shoppers particularly enjoy generous discounts when the store sets aside a Saturday—December 14 this year—for a daylong open house.

Santa Claus patiently listens to wishes from kids of all ages, a band serenades on the patio and several thousand guests come and go during the day to take advantage of bargains. During their stay, they can sample complimentary food items such as snacks, sweets, soft drinks and wine.

Yes, the camels have gone away, but statues and images of the sturdy beasts permeate the store inside and out. They’re reminders of a unique slice of Texas history and the reason for a Hill Country oasis.

Camp Verde's General Store,

Fredericksburg, TX, April 2018. Camp Verde

#CampVerde, #Camels, #ArmyExperiments, #Texas, #TexasHistory, #HillCountry, #WestTexas, #HistoryOfZooAnimals, #ZooAnimals, #Bandera, #KerrCounty, #Kerrville,#USArmyHistory

Whatever Happened to the Wild Camels of the American West?

Initially seen as the Army’s answer to how to settle the frontier, the camels eventually became a literal beast of burden, with no home on the range

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/whatever-happened-wild-camels-american-west-180956176/

https://armyhistory.org/the-u-s-armys-camel-corps-experiment/

features book by Vince Hawkins

https://www.nps.gov/foda/learn/education/upload/Camels%20at%20FODA%20Student.pdf

https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/camels

UPDATE 3.8.2024

Check Replies!

Literal Connections between the Great Pyramid and the Sphinx. Sacred Geometry in the Pyramid and the Bible. Did not the Alpha and Omega create the Physics of it All?

https://steemit.com/greatpyramid/@artistiquejewels/literal-connections-between-the-great-pyramid-and-the-sphinx-sacred-geometry-in-the-pyramid-and-the-bible-did-not-the-alpha-and

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit