Having incarcerated parents perpetuates a cycle of crime, yet there’s little government support for the kids of convicts.

Growing up in the care of someone other than their birth parents can be painful for any child. But research shows children of incarcerated parents face additional struggles, including social isolation and the increased likelihood that they will also end up behind bars.

There are few supports for kids of incarcerated parents in Canada. Just two organizations, the Elizabeth Fry Society of Greater Vancouver and FEAT for Children of Incarcerated Parents in Toronto, provide services specifically for kids with parents in prison.

Yet while both organizations receive funding from their respective provincial governments, neither receives federal funding despite research from federal agency Correctional Service Canada (CSC) that, at one point, it was estimated that more than 350,000 kids — or 4.6 per cent of all Canadian children at the time — were impacted by having fathers in justice and correctional systems.

However, that number is based on an annual count of incarcerated fathers, not the number of parents of the roughly 40,000 Canadians in prison on a daily basis. The same 2007 CSC study estimates as many as 80 per cent of women in prison at the time were mothers of minors, making the actual number of kids affected each year unknown but likely higher than 350,000.

CSC’s research also reveals that these kids are two to four times as likely to grow up to commit crimes themselves. Research in the United States shows they are also more likely to develop poor physical and mental health in young adulthood compared to peers without imprisoned parents.

Shawn Bayes, executive director of the Elizabeth Fry Society of Greater Vancouver, says some kids of incarcerated parents will lie about their status, saying an extended family member looking after them is a foster parent since it’s less stigmatizing to be in care than to have a parent in prison.

That’s why Bayes believes in programs offered by organizations like the Elizabeth Fry Society.

“Programs that are geared for children that just recognize material deprivation or marginalization don’t recognize or support the children around the areas of parental incarceration,” she said, adding many kids face stigma from kids and adults alike, who tell them “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree”.

“They can’t share with their peers or school about what’s going on with them. They’re often kids who are bullied or bullying, because they are trying to address all those issues related to it.”

“I’m not a saint”

CSC’s 2007 study found the majority of kids with dads in prison living with extended family.

That’s the situation for Mary’s family. The 76-year-old great-grandmother has had custody of her granddaughter’s three kids, ages eight to 11, since they were babies. Her granddaughter, who is incarcerated, has been in and out of prisons for over a decade.

“Most people call me a saint, and I tell them I’m not a saint. I’m just looking after the kids,” said Mary, whose name we have changed to protect her family’s privacy.

“Most people say they don’t know how I do it.”

As a relative, Mary receives just over a third of the financial support an unrelated foster parent would get from the Ministry of Children and Family Development. Unlike a foster parent, Mary doesn’t receive support for extra-curricular activities for the kids.

This leaves Mary to make ends meet using the resources of her pension, the Child Tax Benefit, and the $900 the ministry gives her to look after the kids every month. The family depends on free and subsidized programming for the kids, including Elizabeth Fry’s JustKids program for children ages 6 to 18 that consists of a Saturday drop-in, spring and summer camps, and field trips around the Lower Mainland.

“They go somewhere every night,” said Mary about activities that include after-school drop-ins at the local rec centre, the Boys and Girls Club, taekwondo lessons, and JustKids trips such as see Cirque de Soleil, BC Lions games, and the Vancouver Aquarium.

Few people know Mary’s great-grandchildren have a mom in prison, and for good reason. “If it gets out at school, kids could start making fun of them.”

The costs of contact

JustKids is more than a night’s entertainment, says Bayes of EFry. “It is often the first time kids have ever had a chance to meet other kids who have faced the same kind of problems that they do.”

“You can talk about your feelings, what happened to you, what your parents did, whatever — and work out what that means about you and address those fears. You can’t do that in normal circumstances because that information will often see you get bullied.”

While there’s a core group of 300 to 350 children in the program, last year EFry worked with 1,700 kids, 75 per cent of whom are Indigenous or people of colour.

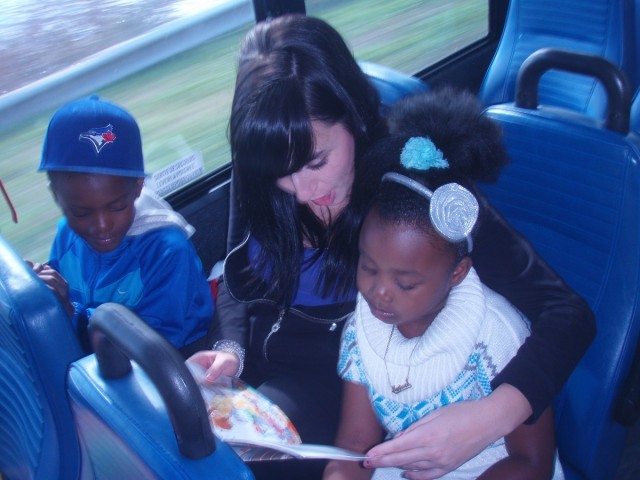

In addition to JustKids, EFry runs the Storybook Program, where volunteers visit nine prisons in B.C. to record incarcerated parents reading a children’s book. The child receives the recording and the book to read along to their parent’s voice. This helps maintain the bond between parent and child that Bayes says is key to ending the cycle of crime perpetuated by having a parent behind bars.

Parents and children can also talk to each other over the phone, but phone calls aren’t free. Bell Canada runs the phone system in federal prisons, and CSC would not comment on the fee citing third-party information protection. Bell Canada told The Tyee via email it would not “disclose terms and conditions of any of our client contracts.”

Provincial prisons in B.C. have a flat fee of $0.90 for a 30-minute local call, while long distance calls to Canada and the United States are $0.80 for the first minute and $0.30 per minute after that. A spokesperson for the provincial Public Safety ministry told The Tyee via email that inmates with jobs in prison typically make $1.50 to $6.50 per shift, but could make up to $9.50 depending on the job.

In an email to The Tyee, a provincial government spokesperson said an unnamed portion of the proceeds go into the “inmate benefit fund” that covers the cost of TVs, cable and other recreational equipment for prisoner use. If prisoners can’t afford the call, some exceptions are made.

Mother and child reunion

All federal prisons offer the Institutional Mother-Child program, which allows some mothers to live with their children in prison up until the age of four. Children up to the age of six can live with their mom part-time. There are currently seven women in federal prisons participating in the program. Over 75 mothers have participated since it began in 1997.

B.C. has a mother-child unit at its Alouette Correctional Centre for Women, which includes a child-bathing area, kitchen, playroom and spaces for moms and babies to live together. Accommodations can also be made for enhanced visitation to breastfeed for moms and babies who are not living together, though the province says these situations are rare.

For mothers with older children or who are not granted the ability to keep their younger child in prison with them, ChildLink is a video conferencing program that lets children and moms visit remotely. EFry helps facilitate the program locally via a Smartboard — an interactive whiteboard with video capabilities — in its New Westminster headquarters.

Bayes says prisons are increasingly relying on video visitations in which parent and child can only see each other via a screen. Unlike ChildLink, families can use a phone, tablet or computer from any location to visit with their family member. CSC confirms that more prisons are implementing this method but denies it’s replacing in-person visitation.

“Video visitation will not replace in-person visits but gives inmates another way to communicate with their visitors if required,” reads an email to The Tyee from Avely Serin, senior communications adviser at CSC.

Parents and families can apply for personal family visits, which are extended visitations in houses located on prison grounds, or even temporary absences where offenders can leave jail escorted or unescorted for family visits or “parental responsibilities” like doctor appointments and teacher meetings. Both programs must be applied for in advance and are granted on an individual basis.

“Society doesn’t seem to care”

But in-person visitation at the prison means families travel there, a tricky feat if they don’t have a car or can’t afford a lengthy bus trip.

In Ontario, the organization Fostering, Empowering, and Advocating Together (FEAT) for Children of Incarcerated Parents has a bus to bring families to prisons and immigration detention centres in southern Ontario every week. But despite visiting federal prisons more often than provincial institutions, it doesn’t receive any funding from the federal government.

“The system needs to look at this research that has been around for a while and continues to show the importance of parent-child relationships and keeping families connected, and then invest in programs that help to do so,” said Jessica Reid, who co-founded FEAT with her father, Derek Reid, in 2011.

FEAT has expanded since 2011 to offer after-school drop-in and mentorship programs for kids and youth ages six to 24 of incarcerated parents across the Greater Toronto Area.

Much like EFry’s JustKids program, FEAT’s aim is to “centre on providing [kids and youth] opportunities to interact with other peers who are going through a similar experience, creating a platform for them to talk about their thoughts and feelings, to build protective factors,” Reid said.

The drop-ins are run by volunteers, including youth leaders who have come up through the program and post-secondary students, of whom 50 per cent had parents in jail. FEAT also runs a summer camp in cottage country for girls seven to 13 who have fathers in prison.

The majority of the 1,000 children FEAT works with every year identify as black, followed by Indigenous, and are mostly low-income. Reid estimates each FEAT program costs $100,000 annually, but other than some provincial funding for specific projects, there is no long-term government support.

“I’ve walked from Toronto to Ottawa, a 400 kilometre walk over 10 days [to fundraise]. I’ve done that twice,” Reid said, adding they also apply for funding through grants.

“Society doesn’t seem to care about those left behind, we just turn a blind eye to it. And that’s why these children have been forgotten. Unless you have gone through this yourself, many have no compassion for these children who have done absolutely nothing wrong.”

Public Safety Canada told The Tyee via email there is funding available for crime prevention programs targeting kids and youth through the National Crime Prevention Program, but to date, neither F.E.A.T. nor the Elizabeth Fry Society of Greater Vancouver have received any program funds.*

While Public Safety Canada does fund the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies for $450,000 through its National Voluntary Organization Grant Program, Bayes says her local organization doesn’t receive any of that money. She added EFry of Greater Vancouver has applied for National Crime Prevention Program grants in the past, but did not receive ministerial approval, nor do the current grants offered through the program seem to apply to JustKids.

“I don’t think people ever think about when a parent goes to prison what happens to their child. I would argue we have a responsibility to do so because Canada signed the [United Nations’] Convention on the Rights of the Child that says you put the child first and consider them in decisions about whether you would separate them from their parents,” Bayes said.

“We don’t recognize these children. They’re invisible.”

Katie Hyslop

TheTyee.ca

Feb 1, 2018

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://thetyee.ca/News/2018/02/01/Helping-Forgotten-Kids-Parents-Prison/

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit