Editorial Board

Toronto Star

Nov 6, 2017

For decades watchdogs and researchers have attempted to draw attention to the disturbing over-representation of Indigenous people in the country’s prison systems.

Yet despite urgent warnings from domestic and international organizations, the latest report from federal prisons watchdog Ivan Zinger makes clear the situation continues to get worse.

Between 2007 and 2016, while the overall federal prison population increased by less than 5 per cent, the number of Indigenous prisoners rose by 39 per cent, Zinger reports.

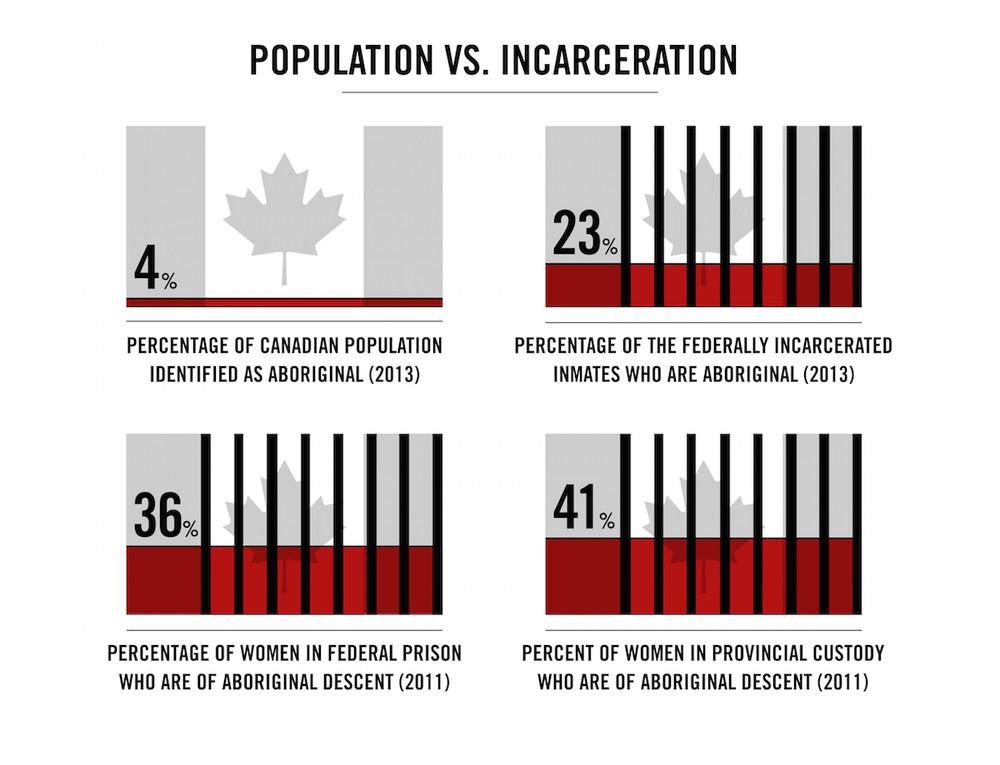

In fact, for the last three decades, there has been an increase every single year in the federal incarceration rates for Indigenous people. While they make up less than 5 per cent of the Canadian population, today they represent 26.4 per cent of all federal inmates. And for Indigenous women the situation is even worse. They comprise 37.6 per cent of the federal female prison population.

As Zinger writes, “The over-incarceration of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people in corrections is among the most pressing social justice and human rights issues in Canada today.”

So what can be done?

The overabundance of Indigenous people in Canadian prisons no doubt reflects larger socioeconomic disadvantages for which there are no simple solutions. Clearly, until governments start taking more aggressive steps to address the poverty, mental health issues and other inter-generational scars of failed colonial policies past and present, the problem will persist.

But in the shorter term, there are a number of simple, long-overdue changes to the court and prison systems that could begin to redress this persistent injustice.

The first is to ensure that the Gladue principle, in place since a 1999 Supreme Court decision, is consistently followed. Under this principle, judges must take into account information, contained in so-called Gladue reports, about an Indigenous person’s background, such as their history with residential schools, child welfare removals, physical or sexual abuse, and health issues such as Fetal Alcohol Syndrome.

Research has shown these reports do affect sentencing, but as legal aid across much of the country shrinks so, too, does the ability of many Indigenous offenders to make courts aware of their particular circumstances. Governments must ensure resources are in place to allow the court system to truly abide by this important principle.

The Zinger report contains other valuable suggestions. For one, it recommends that finally implement proposals from the 2016 federal auditor general’s report to more quickly get Indigenous offenders out of jail and reintegrated into society.

The auditor general found that in 2015-16 most Indigenous offenders weren’t released from custody until their statutory release date, after serving two-thirds of their sentence. Of those, 79 per cent were released into the community directly from a maximum or medium security institution “without benefit of a graduated and structured return to the community.”

Nor was Corrections Canada effectively getting Indigenous prisoners into programs within jails that could help them upon their release. Only 20 per cent were able to complete their programs by the time they were eligible for parole.

In response to the AG’s report, Corrections Canada promised to expand programs tailored to the needs of Indigenous offenders, including preparing them for early release. Yet Zinger found that Indigenous prisoners continue to be released just as late, likely in part because the parole board remains unsatisfied that applicants have in fact been adequately prepared to reenter the community.

This lack of preparation partly explains, too, why Indigenous offenders are so much more likely to be returned to prison due to the suspension or revocation of their parole. And once inside, Indigenous prisoners suffer more than others: they are over-represented in segregation cells, use-of-force interventions, maximum-security institutions and incidents of self-injury.

Canada’s shameful history of Indigenous injustice continues to play out graphically and painfully in our courts and prisons, which both reflect and reinforce these communities’ disadvantage. But the justice system need not deepen these inequalities; indeed, it can play a role in healing Indigenous communities and Canada’s relationship with them. Reversing the over-representation of Indigenous people in our prison population is an important measure of reconciliation.

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.thestar.com/opinion/editorials/2017/11/06/what-to-do-about-the-overrepresentation-of-indigenous-people-in-prisons-editorial.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit