Introduction:

Every year, every other English language blog, expat website or whatever will write an article attempting to tell you what a wonderful Chinese tradition eating Mooncakes to celebrate the Mid-Autumn festival is, even though the vast majority of people don’t even actually enjoy eating them. Just like the fillings in the cheaper mooncakes sold in many a mom and pop store, those articles are stale and probably reused from the year before.

Rather than telling you a wonderful story about a secret plan (hidden in mooncakes of course) to kill the Mongols (or any of the other festive myths) or how much fun it is to stare at the moon, I’m focusing solely upon the mooncakes themselves in this article.

Does anybody actually eat them?

Some people obviously do. If one was to haphazard a guess, one would expect that the elderly would be the ones most likely to cling onto the that tradition of eating packed full of (in most, but not all cases) so much pork lard and sugar. They may be compared to fruitcakes, a seasonal gift in the West that everyone seems to love to hate (Lau, 2014). So, you’ve always heard that story about Spring Festival being like ‘Chinese Christmas?’ Mooncakes are the equivalent of that fancy looking Panettone that everybody seems to receive at Christmas but not actually eat.

One may doubt that the mooncake tradition in its current form will be passed onto the future generations as Mooncakes seem to have greater importance as a guanxi/business relationship building gift than as an actual food product. Despite boxes of mooncakes often costing over $100 USD, they are usually all very similar in nature and often end up being quickly disposed of soon after the festival; Hong Kong alone disposed of around 2 million mooncakes in 2012 (Chen, 2013).

What’s more important, the filling or the price and presentation?

As mentioned just now, most traditional mooncakes are quite similar in nature, no matter how much you pay for them; you may be getting the same thing; even the best 5 star hotels with high class patisserie shops are often rumoured to outsource their mooncake production to mass producers. Of course, some people do get quite inventive these days as we will discuss later.

However, this all matters not when one takes into account the darker side of mooncake giving; its role in bribery may often mean that the mooncakes themselves are of little significance, elaborate packaging may go far even beyond a beautifully decorated box, it is not unknown for the presentation boxes to include a little something extra that pushes the true price of a supposedly simple gift into the range of tens of thousands of US dollars (Szto, 2016).

Such is the prevalence of the mooncakes in crossing that fine line between cultivating guanxi and outright bribery that Western businessmen have in recent times been warned to carefully consider the ethical implications of mooncake giving (Ives, 2012). Despite this, mooncakes remain big business despite recent government gift giving/anti-corruption clampdowns (Lau, 2014). It will probably forever remain that way, even if the nature of mooncakes eventually change with time.

Traditional vs. Modern Fillings:

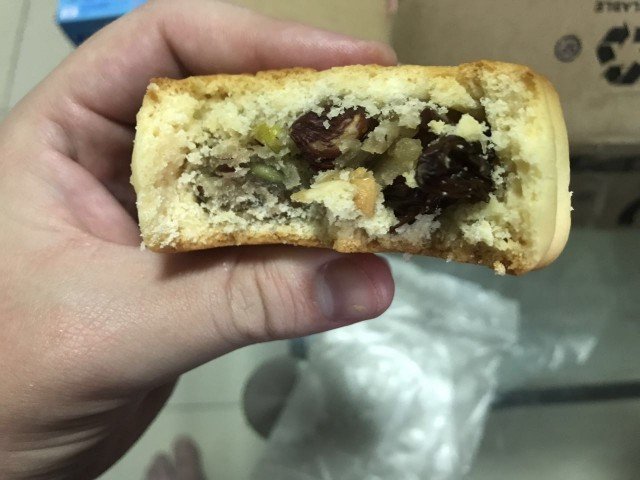

According to Tang and Yin (2010, pg.439), there are two traditional types of traditional moon cake, one stuffed solely with lotus seed paste; the other stuffed with an additional egg yolk in the centre (most likely to be a salted duck egg yolk). Of course, those who have lived in China possibly know of many other fillings that can be considered traditional, such as mixed nuts, red bean paste etc.

There are also many regional variations such as the flaky skinned mooncakes hailing from Suzhou, that may contain fillings such as Jinhua ham, thus possibly making the closest Chinese equivalent to an English style pork pie. Some crazy Laowai tried to recreate this with prosciutto and dates twist (Lady and Pups, 2015), but now let’s look at how the Chinese people themselves are getting all creative with totally modern variations of the mooncake.

Chocolate and ice cream mooncakes, or even just mooncake shaped extra thick slabs of chocolate are now a thing (Ives, 2012). Häagen-Dazs of course brought the ice-cream mooncake to the world; becoming the first ice-cream manufacturer to enter China’s B2B gift market (Poleg, 2012); although one would certainly hope that some of those ice-cream mooncakes do actually get purchased for non-business related purposes.

Snowskin mooncakes are also another recent innovation; hailing from Hong Kong, these like the ice cream mooncakes are also served chilled. These were launched in response to the belief that customers were getting bored with mooncakes in their traditional form (Wong, 2004).

Not only are the fillings changing, the shapes are too. Examples include mooncakes shaped like buttocks, cartoon characters and emojis (Lau, 2014). There appears to be a question waiting to be asked; ‘do today’s consumer really wish to give and receive mooncakes, or deep down would they prefer something else?’

Why mooncakes will never die:

People’s beliefs in the myths regarding the origins of the festival may have faded with time, yet the mid-autumn festival is still an important celebration for Chinese people, especially has it has in modern times become an occasion for family reunions (Yang, 2006, pg.265-267). This a factor that has most likely increased in importance as those from rural backgrounds are nowadays often forced to leave their hometowns behind to seek employment.

Mooncakes also have greater significance as more than just merely being food products; they visually or materially represent Chinese culture by carrying on traditions over many years; they represent an opportunity to reaffirm one’s identity, especially when it comes to the value that is placed upon commodities such as mooncakes that are given or eaten during the celebration of the festival (Hulsbosch et al, 2009, pg.22).

It is for this reason that even if the fatty and sugary mooncakes of old die out over future generations, the practice of giving mooncakes to family members, business partners or government officials will still carry on. Regardless of if we all move onto more modern mooncake variations made according to newer recipes, or worse yet, we all start sending each other some kind of digital version of mooncakes via WeChat, mooncakes will survive. Mooncakes will forever continue to live on; even though we will all continue to secretly hate them, no matter how grateful we will pretend to be when we receive them.

References:

Chen, T. 2013, Garbage Gift: Hong Kong Threw Away 2 Million Mooncakes. Available: https://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2013/09/10/green-groups-fight-mooncake-deluge/

Hulsbosch, M., Bedford, E., & Chaiklin, M. (eds), 2009, Asian material culture, Amsterdam Univ. Press, Amsterdam.

Ives, M. 2012, The Mooncake: A Treat, a Bribe or a Tradition Whose Time Has Passed? Available: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/the-mooncake-a-treat-a-bribe-or-a-tradition-whose-time-has-passed-56793351/

Lady and Pups, 2015, PROSCIUTTO AND DATES SU-STYLE MOONCAKE. Available: http://ladyandpups.com/2015/09/25/prosciutto-and-dates-su-style-mooncake/

Lau, J. 2014, Mooncakes Are a Must as Chinese Festival Nears. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/06/business/international/millions-of-mooncakes-as-chinese-festival-approaches.html

Poleg, D. 2012, Häagen-Dazs China: Let them eat mooncake. Available: http://www.buybuychina.com/haagen-dazs-china-let-them-eat-mooncake/

Szto, M. 2016, "Chinese gift-giving, anti-corruption law, and the rule of law and virtue", Fordham International Law Journal, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 591.

Tang, C.S. & Yin, R. 2010, "The implications of costs, capacity, and competition on product line selection", European Journal of Operational Research, vol. 200, no. 2, pp. 439-450.

Wong, S. 2004, Mooncakes. Available: http://thingsasian.com/story/mooncakes

Yang, L. 2006, "China's Mid-Autumn Day", Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 263-270.