This article is written by the CoinEx Chain lab. CoinEx Chain is the world’s first public chain exclusively designed for DEX, and will also include a Smart Chain supporting smart contracts and a Privacy Chain protecting users’ privacy.

Introduction to packages of OnvaKV

Here we introduce the packages and the data structures defined in the OnvaKV repo.

OnvaKV

OnvaKV has three building blocks: index-tree, data-tree, and meta-db.

+----------------+

| |

| OnvaKV |

| |

+----------------+

/ / \

/ / \

/ / \

/ metadb \

/ | datatree

indextree | / \

/ \ | / \

/ \ | entry-file twig-merkle-tree-file

/ \ | \ /

/ \ | \ /

B-Tree RocksDB \ /

(cpp&go) \ /

Head-Prunable File

Head-Prunable File

See datatree/hpfile.go

Normal files can not be pruned(truncated) from the beginning to some middle point. HPFile use a sequence of small files to simulate one big file. Thus, pruning from the beginning is to delete the first several small files.

A HPFile can only be read and appended. Any byteslice which was written to it is taken as readonly can not be overwritten.

You can use Append to append a new byteslice into a HPFile, and Append will return the start position of this byteslice. Later you can pass this start position to ReadAt and read this byteslice out. The position passed to ReadAt must be the beginning of a byteslice, instead of its middle.

A HPFile can also be truncated: discarding the content from the given position to the end of the file. All the byteslices written to a HPFile during a block should be taken as one whole atomic operation: all of them exist or none of them exists. If a block is half-executed because of machine crash, that is, some of the byteslices are written and the others are not, then the written slices should be truncated away.

Entry File

See datatree/entryfile.go

It uses HPFile to store entries, i.e., the leaves of the data tree. The entries are serialized into byteslices in such a format:

- 8-byte MagicBytes, which is

[]byte("ILOVEYOU"). We use MagicBytes to mark the beginning of an entry. In the entry file, you can find MagicBytes only at the beginning of every entries. If you read bytes out from a entry file and the beginning of these bytes is not "ILOVEYOU", then the read position must be wrong. This makes coding and debugging easier. - 4-byte Total Length (this length does not include padding, checksum and this field itself), in little endian. Using this information, you can fast skip an entry and access the next.

- Int32 list of MagicBytes positions, which uses

-1as the ending. Each Int32 takes 4 bytes, in little endian. Every position (except the last-1) gives a position where has 8 zero bytes and should be replace by MagicBytes. These posistions are relative to the end of 4-byte Total Length. - An entry's content, including: 4-byte key length, key's bytes, 4-byte value length, value's bytes, 4-byte next key length, next key's bytes, 8 bytes of height, 8 bytes of last height, 8 bytes of serial number. All these integers are little endian.

- Int64 list of deactived serial numbers. , which uses

-1as the ending. Each Int32 takes 4 bytes, in little endian. After the creation of last entry and before the creation of current entry, zero or more entries are deactived, and their serial numbers are recorded in this list. - 4-byte checksum, calculated using meow hash.

- Several zero bytes for padding. The size of the serialized bytes must be integral multiple of 8.

By adding list of deactived serial numbers into entries, we make an entry file into a log file. If all the information in memory is lost, we can re-scan the entry file from beginning to end to rebuild all the state.

An entry's hash id is sha256 of its serialized bytes, which means the list of deactived serial numbers is also proven by the merkle tree. If you receive an entry file from an untrusted peer, you can verify its entries with the merkle tree.

Twig Merkle Tree File

See datatree/twigmtfile.go

It uses HPFile to store small 2048-leave small Merkle tree in a twig. When someone queries for the proof of an entry, we can use this file to read the nodes in the small Merkle tree.

Each node occupies 36 bytes: 32 bytes of hash id and 4 bytes of checksum. There are 4095 nodes in the 2048-leave small Merkle tree, and they are numbered in such way:

1

/ \

/ \

/ \

/ \

/ \

/ \

2 3

/ \ / \

/ \ / \

/ \ / \

4 5 6 7

/ \ / \ / \ / \

/ \ / \ / \ / \

8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Node 1 is the root, and 2 and 3 is its left child and right child. Generally, node n has 2*n and 2*n+1 as its left child and right child. There is no node numbered as 0. The 2048 leaves in the tree are numbered from 2048~4095.

In the twig Merkle tree file, we also stores the first entry's position of each twig, which shows the postion where we can find the first entry of a twig in the entry file. This information occupies 12 bytes: 8 bytes of position and 4 bytes of checksum.

So totally, a twig uses 12+36*4096=147468 bytes in the twig Merkle tree file.

Datatree

See datatree/tree.go

This is most important data structures. Youngest twig, active twigs and pruned twigs are all implemented here. Most of the code are related to incrementally modify the Merkle tree by appending new leaves and deactive old leaves, which are performed in a batch way after each block.

Major Components

A datatree keeps the following major components:

- The entry file

- The twig Merkle tree file, which stores the left parts of all twigs, except the youngest one

- The left part of the youngest twig

- The right parts of all active twigs (the right parts of the inactive twigs are all same)

- The upper-level nodes whose are ancestors of active twigs

The components 3, 4 and 5 are stored in DRAM and volatile. So to stop OnvaKV in a friendly way, these components should be serialized and dump to disk, after a block is fully executed. When OnvaKV is stopped unexpectedly (for example, because of machine crash), the components 3, 4 and 5 will be lost, and their state must be rebuilt from components 1 and 2.

A datatreee also keeps some minor components, which are temporary sratchpad used during block execution. When a block is fully executed, the contents of these components will be cleared.

Buffering the right part of youngest twig

The right part of a twig is a Merkle tree with 2048 leaves. When a new twig is allocated as the youngest one, all its leaves are hashes of null entry, whose Key, Value and NextKey are all zero-length byteslices and Height, LastHeight and SerialNum are all -1.

As new entries are append into the youngest twig, more and more leaves are replaced by hashes of non-null entries. And the 2048-leave Merkle tree changes gradually. We record this gradually-changing left part of the youngest twig in the variable mtree4YoungestTwig.

After 2048 entries are appended, the right part can not change anymore, so we flush it into the twig Merkle tree file and then allocate a new Merkle tree in mtree4YoungestTwig, as the youngest one.

Evicting twigs and pruning twigs

When a twig's active bits are all zeros, its right part can not change any more. So we can evict it from DRAM to make space for newly-generated twigs.

The aged twigs will undergo the compaction process, during which the valid entries are read out, marked as invalid and re-append the youngest twigs. Compaction ensures we can always make some progress in evicting old twigs.

Pruning twigs is another operation, which is totally different from evicting. Pruning twigs means prune the entries and left parts of old twigs from hard disk. The twig Merkle tree file and the entry file are all implemented with head-pruneable files, so they support pruning the records at the head.

Upper-level nodes

In datatree we use the variable nodes to store the upper-level nodes, which are acestors of non-pruned twigs.

The variable nodes is just a golang map, which values are hash IDs stored in nodes, and keys are positions. How to present the position of a node in a Merkle tree? If a node is the N-th node at level L, the its position is calculated as an integer (L<<56)|N. A node with postion of (L, N) has two children: (L+1, 2*N) and (L+1, 2*N+1).

A root node is the node whose level is the largest among all the nodes.

The null twig and null nodes

OnvaKV uses balanced binary Merkle tree whose leave count is $2^N$,. If the count of entries is not $2^N$, we just add null entries for padding, concepturally . In the implementation, we do not really add so many null entries for padding. Instead, we just add at most one null twig and at most one null node at each level. In a null twig, all the active bits are zero and all the leaves are null entries. For a null node, all its descendant (downstream) nodes and twigs are null. The null twig and null nodes are pre-computed in the init() function.

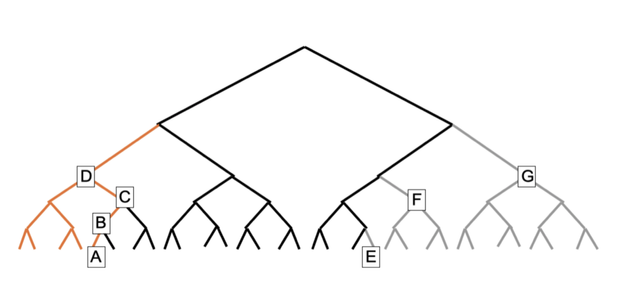

In the following figure. E is a null twig while F and G are null nodes. We do not keep the grey portion in DRAM and hard disk, because these twigs and nodes are all null. Instead, storing E, F and G in DRAM is enough to providing proof for every valid entry.

The edge nodes

In the above figure, the first four twigs are pruned to save space of hard disk. If we discard all the orange portion of the Merkle tree, some entries will be impossible to be proven. So we must still keep the nodes A, B, C and D in DRAM. These nodes are called "edge nodes" because they are at the left edge of the remained tree. A node is an edge node if and only if:

- It is the twigRoot of just-pruned twig, i.e., whose twigID is the largest among all pruned twigs.

- It has both pruned-descendants and non-pruned-descendants.

If pruning is performed in a block, then the edge nodes must be saved to database when this block commits, to keep data consistency.

Batch sync

The datatree gets changed because of two kinds of operations: appending new entries and deactivating old entries. If we synchronize the Merkle tree after each operation, the amount of computation would be huge. So we prefer to finish all the appending and deactivating operations in a block and then use batch-mode synchronization to make the Merkle tree consistent.

Synchronization has four steps:

- When the left part of the youngest twig is ready to be flushed to hard disk, this 2048-leave tree get synchronized. This synchronization can run multiple times during a block's execution.

- When a block finishes execution, the left part of the youngest twig get synchronized.

- When a block finishes execution, all the right parts of twigs get synchronized.

- When step 2 and 3 finish, the upper level nodes get synchronized.

During step 2, 3 and 4, the hash computations of the same level are independent with each other, so we can run them parallelly.

Rocksdb

See indextree/rocks_db.go

RocksDB is a KV database written in C++. It has a Golang binding, which is not so easy to use. Tendermint wraps the binding for easier use. We refined Tendermint's wrapper to support pruning.

RocksDB supports filtering during compaction, which is a unique feature among all the opensource KV databases. We use this feature in indextree.

In OnvaKV there is a rocksdb database. Both metadb and indextree use it to store some information which is not performance-critical but important for consistency. All the updates generated during one block is kept in one batch, to make sure blocks are atomic. If the batch commits, the block commits. If the batch is discarded, it looks as if the block does not execute at all.

metadb

See metadb/metadb.go

We need to store a little meta information when a block finishes its execution. The data size is not large and not performance critical, so we store them in RocksDB.

When OnvaKV is not properly closed, we should use the information in metadb as guide to recover the other parts of OnvaKV.

The following data are stored in metadb:

- CurrHeight: the height of the latest executed block

- TwigMtFileSize: the size of the twig Merkle tree file when the block at CurrHeight commits.

- EntryFileSize: the size of the entry file when the block at CurrHeight commits.

- OldestActiveTwigID: ID of the oldest active twig, i.e., this ID is the smallest among all the active twigs.

- LastPrunedTwig: ID of the just-pruned twig, i.e., this ID is the largest among all pruned twigs.

- EdgeNodes: the edge nodes returned by

PruneTwigs. - MaxSerialNum: the maximum serial number of all the entries. When a new entry is appended, it is increased by one.

- ActiveEntryCount: the count of all the active entries.

- IsRunning: whether OnvaKV is running. When OnvaKV is initialized, it is set to true. When OnvaKV is closed properly, it is set to false. If it is found true during initialization, it means OnvaKV was NOT closed properly, and you should recover the data.

- TwigHeight: a map whose key is Twig's ID and value is the maximum value of its entries' heights. When OnvaKV is asked to 'prune till a given height', this map is used to show which twigs can be pruned.

When OnvaKV is NOT properly closed, TwigMtFileSize and EntryFileSize may be different from the real file size on disk, because of the last block's partial execution. Before recovering, the twig Merkle tree file and entry file would be truncated to the TwigMtFileSize and EntryFileSize stored in metadb, respectively.

B-tree

We include two B-tree implementations. One is a Golang version from modernc.org/b (indextree/b/btree_nocgo.go), and the other is a C++ version from Google (indextree/b/cppbtree/btree.go and indextree/b/btree_cgo.go). Why there are two versions? Because we do not have 100% confidence of either one of them. So we use fuzz test to compare their outputs. If the outputs are the same, then most likely they are both correct, because they are implemented independently and hard to have the same bug.

In production, the C++ version is preferred. Because:

- The B-Tree will use a lot of memory. The C++ version doesn't use GC, so it will be faster.

- We can use a trick to save memory when the key's length is 8.

This trick is from the old wisdom of embedded systems. It utilizes the fact that pointers are aligned, that is, the least significant two bits is always zero. So, when the key's length is 8 and the least significant two bits of its first byte is not 2'b00, we do not need to store a pointer to byte array, instead, we can store the byte array within the 8 bytes occupied by a pointer. (Note that x86-64 and ARM64 uses little endian, which means the least significant two bits of an int64 locate in the first byte of an array.)

We use B-Tree because it's much more memory-efficient that Red-Black tree and is cache friendly.

indextree

See indextree/indextree.go

We implement indextree with an in-memory B-Tree and a on-disk RocksDB, which is shared with metadb. The B-Tree contains only the latest key-position records, while the RocksDB contains several versions of positions for each key. The B-Tree's keys are original keys while the keys in RocksDB have two parts: the original key and 64-bit height. The height means the key-position record expires (get invalid) at this height. When the height is math.MaxUInt64, the key-position record is up-to-date, i.e., not expired.

When we execute the transactions in blocks, only the latest key-position records are used, which can be queried fast from in-memory B-tree. The RocksDB is only queried when we need historical KV pairs. But, during executing the transactions, the RocksDB is written frequently, which is also an overhead. So if you do not care about historical KV pairs, you can turn off this feature.

The RocksDB's content is also used to initialize the B-Tree when starting up. When height is math.MaxUInt64, the KV pair is up-to-date and must be inserted to the B-Tree.

If we no longer need the KV-pairs whose expiring height are old enough, they can be filtered out during compaction: this is how pruning works.

Top of OnvaKV

See onvakv.go

It integrates the three major parts and implement the basic read/update/insert/delete operations. The most important job of it is to keep these parts synchronized. It uses a two-phase protocol: during the execution of transactions, it perform parrallel prepareations to load "hot entries" in DRAM; when a block is committed, it updates these parts in a batch way.

During a block's execution, we say an entry is "hot" when:

- It may be a newly-inserted entry

- Its Value may be updated

- Its NextKey may be changed because a new entry will be inserted next to it.

- Its NextKey may be changed because the entry next to it may be deleted

We use the word "may" here because in individual transaction in a block may succeed or fail during execution. If it succeed, the KV updates made by it will take effect. If it fail, the KV updates will be discarded.

To support parallel execution of transactions, we use a sync.Map to cache the hot entries. This cache is valid only during a block's execution. When a block commits, it is cleared.

During a block, this cache undergoes a filling phase, a marking phase and a sweeping phase. In the filling phase, many transactions can concurrently add new hot entries to this cache, using the PrepareForUpdate and PrepareForDeletion functions. In the marking phase, only the succeeded transactions marking some of these hot entries to be inserted, changed or deleted, using the Set and Delete functions. In the sweeping phase, the cached hot entries are sorted according to their keys and then we scan these sorted hot entries to update datatree.

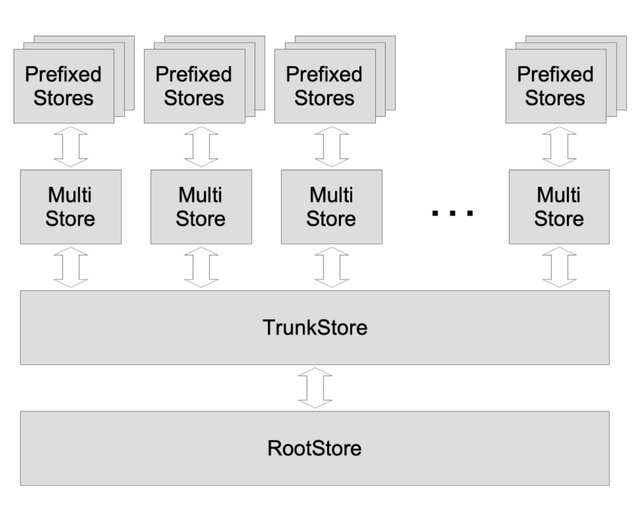

Store Data Structures

The API of OnvaKV is somehow hard to use because you must follow the three phases of the hot entry cache. It would be better to wrap it with some "store" data structures to provide an easy-to-used KV-style API. The figure below shows the relationship among these "store" data structures.

PrefixedStore

|

|

MultiStore

| \

| \

TrunkStore \

| \ \

| \ \

RootStore \ \

| CacheStore

|

OnvaKV

There are three levels of caching with different lifetimes: RootStore's cache lasts for many blocks, TrunkStore's cache only exists during a block and MultiStore's cache only exists during a transaction.

During run time, the relationship of these stores are shown as below.

Each transaction has its own MultiStore, based on which there are several PrefixedStore. Each transaction's MultiStore can access the block's TrunkStore. When block is committed, contents in TruckStore are flushed to RootStore.

The transactions in a block are divided into several epochs. Inside an epoch, transactions are independent, and among epochs, they are dependent. So we execute all the transactions of one epoch in parallel, and then switch to the next epoch when finished. This algorithm's detail is show below:

- Allocate a new TrunkStore for a new block

- Fetch an epoch of transactions from the block

- Execute these transactions in parallel, which read and write their own MultiStore, and at the same time, read the shared TruckStore and RootStore

- For the succeeded transactions, flush their caches to TrunkStore, and for the failed ones, discard their caches.

- Repeat step 2 to 4 until there are no more epochs

- Flush the TrunkStore's cache to root cache

Lazy Serialization

The values stored in the caches are serializable objects, instead of plain byteslices.

type Serializable interface {

ToBytes() []byte

FromBytes([]byte)

DeepCopy() interface{}

}

Serializable objects allow "lazy serialization". These objects undergo serialization/deserialization only when they are read out from and written to the entry file. When being transferred among these caches and the application's logic, they are just plain pointers.

The stores all support serializable objects. They are so-called "Key-Object stores", instead of plain "Key-Value stores". They support following Get* functions:

- Get: return the serialized byteslices of the object

- GetObjCopy: return a deep copy of the object

- GetReadOnlyObj: return the object itself, but the transaction should not modify the object

The MultiStore and PrefixedStore only serves one transaction, so they can support one more function:

- GetObj: return the object itself, and record that this object's ownership is transferred out. The client code cannot use GetObj twice at the same key, and the code must use SetObj to return back the ownership later.

RootStore and TrunkStore cannot support GetObj because the object's ownership will never be returned back if the transaction fail.

CacheStore

See store/cache.go.

It uses the Golang version of B-tree to implement an in-memory cache for overlay. It buffers all the changes to the underlying store, including value-updating, insertion and deletion. ScanAllEntries can iterate all these buffered changes. It is used to dump these changes to the underlying store.

CacheStore shadows (overrides) the underlying store. If a key hits on the cache, then the cached status (existence and value) will take precedence over the underlying store.

CacheStore's iterator does not skip deleted keys. Instead, it returns a nil key to signal it is pointing to an deleted item.

A cacheMergeIterator merges a parent Iterator and a cache Iterator, and provides a clear interface to outside. If the cache iterator has the same key as the parent, the cache shadows (overrides) the parent.

RootStore

See store/root.go.

It survives many blocks to provide persistent cache for frequently-reused data. Its cache is just a plain golang map map[string]Serializable. Its cache is not used to add an overlay. Instead, it is more like a file system cache in memory to avoid reading entries from hard disk. It only caches readonly objects, such as parameters which can be configured by proposals. You can further control which readonly objects can be cached by providing isCacheableKey func(k []byte) bool, which returns true for keys whose value need to be cached.

TrunkStore

See store/truck.go.

It is for one block's execution, with a cache overlay. When a TrunkStore is closed, you can choose to write back its contents or not. Once the write-back process starts, it cannot be read or written any more.

MultiStore

See store/multi.go.

It is for one transaction's execution, with the cache overlay. It is named as "multi" because there are multiple MultiStores built upon a TrunkStore. When a MultiStore is closed, you can choose to write back its contents or not. Normally, the MultiStore is write back when a transaction succeeds.

PrefixedStore

See store/prefix.go.

It helps to divide a MultiStore into several "sub stores", each one of which has a unique key prefix. Every operation on PrefixedStore, will be performed on the underlying MultiStore, with the keys be prefixed.

The Rabbit Store

See store/rabbit

RabbitStore is a special KV store which uses short fixed-length keys for indexing. We can replace MultiStore with it to reduce DRAM usage.

Rabbits hop to store and eat carrots

To explain how RabbitStore works, let's tell a story of rabbits first.

There are 24 holes, each of which can hold a carrot. Rabbits come and put their carrots into holes according to given algorithm. Suppose now eight rabbits have come and put eight carrots in eight holes. Then the Alice rabbit is coming with her carrot which is named as "Alice's yummy carrot". Alice will do the following steps according to the algorithm:

- She hashes the name "Alice's yummy carrot" once and gets a number 13 . She hops to the #13 hole and finds another carrot in it. So her carrot cannot be stored in this hole.

- She hashes the name twice and get a number 22. She hops to the #22 hole and finds another carrot in it. So her carrot cannot be stored in this hole either.

- She hashes the name for three times and get a number 21. She hops to the #21 hole and finds an empty hole. So she can store "Alice's yummy carrot" in it.

- She places one stone at #13 hole and one stone at #14 hole, which mean she must pass by these holes to reach the correct hole storing her carrot.

Finally, the Bob rabbit is coming with his carrot which is name as "Bob's delicious carrot". He does similar steps as Alice. He hops to #22 hole first, and then hops to #11 hole, finding these holes are full. At last he find an empty #9 hole. He stores his carrot in #9 and place two holes at #22 hole and #11 hole.

Now, we can see #13 hole and #11 hole each have one pass-by stone, and #22 hole has two pass-by stones.

When a rabbit comes to eat her carrot, she must follow these steps:

- Set n = 1

- Hash her carrot's name for n times and gets a hole number, and then check the hole:

- If her carrot is not there and there is no pass-by stone, her carrot can never be found (maybe eaten by someone else)

- If her carrot is not there and there are one or more pass-by stone, set n = n + 1 and go to step 2.

- If her carrot is there, she eats it and removes one pass-by stone from each hole she just passed by.

If there are empty holes, a rabbit can finally find one hole to store her carrot in finite steps. And if the carrot is still there, a rabbit can finally find it to eat in finite steps.

Short fixed-length keys for indexing

The C++ version B-tree uses a special trick to reduce memory usage which only works when the key is 8 bytes long. But in practice, keys are usually quite long just like a carrot's lengthy name.

There are no more than 264 holes (because the key is 8 bytes long), and we must assign a hole number to some carrots with unique names. The number of carrots are far less than 264, but their names are much longer than 8. The rabbits' hopping algorithm can help us map lengthy names to 8-byte hole number.

In the underlying TrunkStore, the keys are 8-byte which are calculated . And the original variable length key-value pairs are packed together and used as the values stored in TrunkStore

By hashing the original keys, RabbitStore gets new 8-byte short keys. By packing the original variable-length key and value together, RabbitStore gets new values. These new keys and values are stored into the underlying TrunkStore. Thus the indextree only faces fixed 8-byte short keys, which allows C++ B-tree to do the trick.

The short 8-byte keys generated from adjacent original keys, will no longer be adjacent to each other any more. So RabbitStore cannot support iteration. Luckily, EVM only uses SSTORE and SLOAD to access the underlying persistent KV store and it does not need iteration at all.

Performance Consideration

The possibility of rabbits' hopping path drops exponentially as its length grows. In practice, almost all of the hopping paths have only one hop. So the performance penalty of RabbitStore is negligible.