The summer/autumn of 1989 was a period of great change in Europe, leading to the end of communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall. But have all the changes been positive – for the east and west?

On Sunday September 3, 1989, I set out from Britain to spend three weeks on the European continent. It was a historic date, because fifty years earlier, on that very same day World War II had broken out. Little did I know that tumultuous political changes would be occurring in 1989 too.

I took the ferry to Calais and then a train to Paris. The first week of my European adventure was spent in the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), in Bavaria, where I stayed with the family of my German pen-friend, Gabi. I was very well-looked after and had a great time. It was the third time I had visited West Germany and I had always been impressed.

Someone wrote recently that there needs to be more focus on post-war West Germany and its many achievements, and a bit less on pre-war Nazi Germany. I’d agree. The old Cold War was framed in terms of ‘capitalism v communism’ but that was very simplistic. West Germany operated a mixed-economy – with economic success fueled by local State banks and provided a generous welfare state to its citizens which worked very well. It was a far cry from rapacious dog-eat-dog 1920s US capitalism. Conversely, Hungary’s ‘goulash communism’ had elements of a market economy.

© Reuters / FAB

After West Germany, I travelled down to Yugoslavia, or rather the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, to give the country its official title. I stayed in a pension in the Julian Alps, near Lake Bohinj (in today’s Slovenia) run by a very generous and charismatic pro-partisan. This man didn’t just espouse egalitarian ideals, he lived them.

Each evening he would invite myself and his other guests to sit, eat, drink and smoke with him and he would tell daring tales of how the partisans defeated the Nazis in WWII. He was a wonderful host. He even took in guests’ laundry for washing for no extra charge. The only time I saw him slightly agitated was when he had to take our passports to the local police to register us.

One sensed there would have been repercussions had he failed to do so. But my general impressions of socialist Yugoslavia were positive. I remember going to Ljubljana and being surprised to see English newspapers freely on sale. The place had a real buzz.

After Yugoslavia, I headed back into West Germany, via Austria, and made my way to Frankfurt for the third and final leg of my journey. I had long wanted to visit the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), to see for myself what life was really like behind the so-called ‘Iron Curtain’.

A very nice lady who lived up our road when I was a child, was an émigré from East Germany and told us that whenever she went back to visit her family she was followed around by the secret police. Sounds pretty bad now, but to a twelve-year-old growing up in seventies Britain, brought up on a diet of spy films and war-time adventures, it all seemed quite exciting. I had an East German pen-friend called Stefan, who lived in Karl Marx Stadt, and we exchanged football news and team pennants by post.

© Neil Clark

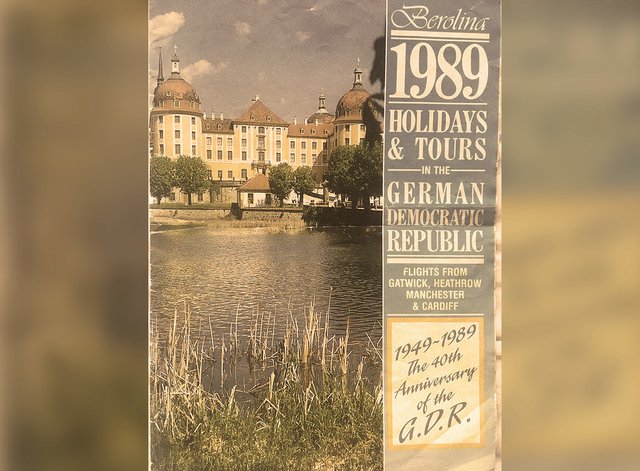

“Make 1989 the year you visit the GDR,” was the exhortation in the brochure of Berolina Travel, the East German state travel agency, so myself and my university friend Rob decided to take them up on the offer. The timing could not have been better. The ‘Workers State’ created ‘Aus Ruinen’ (out of the ruins) of WWII, with an absolutely stirring national anthem (whatever your views are on communism you'll surely agree ), was celebrating its 40th birthday.

‘40 Jahre DDR’ placards and posters were everywhere. They say life begins at forty, but incredibly Europe’s youngest country reaching that milestone marked its death throes. There was certainly no sign of impending collapse when we entered the GDR on September 16, 1989, yet astonishingly just two months later the Berlin Wall was being torn down.

I have been to over fifty countries, but my visit to East Germany was one of the most memorable. As I wrote in my write-up of the holiday entitled ‘Where the Past is Another Country’:

“The blandness and uniformity of most modern airports has taken a lot away from that most vivid of life’s experiences: arriving in a foreign country for the first time. However, with electric fences, barbed wire and look-out towers as far as the eye could see, not to mention the armed border guards and their obligatory snarling Alsatians, arriving in East Germany for the first time could be described as anything but bland and forgettable.”

Our first night in the GDR was spent sleeping on benches on the platform at Erfurt station, as all four of the town’s state-run Inter-Hotels were fully booked. I remember a friendly policeman helping us up the stairs with our luggage. The next day we traveled cross-country by train (it was the first time I'd seen a female train driver) to our base for the week, the Hotel Zur Post in the very picturesque town of Wernigerode, in the Harz Mountains. It was a fantastic week. The weather was glorious and we made plenty of trips, as well as going on some long hikes.

One morning a beautifully maintained red Morgan sports car drove up outside the hotel and out came a quite elderly British tourist. He told us he came to the GDR every year on a motoring holiday and absolutely loved it. I remember being in a park, sitting by a tree and listening to the radio. A gardener who was sweeping up leaves kept looking at me and then went off. He returned with a policeman. ‘Are you Hungarian?‘ he asked me.

At the time, East Germans were leaving the country through the Hungarian-Austrian border, so perhaps that’s what prompted his question. He asked to see my passport and asked where I was staying, and that was that. It was the only ‘brush’ with officialdom we had throughout our whole stay. We made friends with a lovely married couple who we chatted to each night at our hotel. They like me were big fans of detective fiction and loved the works of Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and Edgar Wallace.

The biggest gripe they had with the system – which provided full employment, social security from the cradle to the grave, and very safe streets, were the travel restrictions. They would love to have visited Britain but couldn’t.

It was a common grievance. The people who took to the streets marching for change were not calling for the introduction of Thatcherism, as the BBC series ‘The Lost World of Communism’ showed. Most people wanted to keep the best of the socialist system but have more freedoms. Most of all they wanted a World Passport, which was granted in early November 1989, but by then it was too late. After the Wall came down I received an ecstatic letter from the couple we had befriended in Wernigerode which ended with the word ‘FREIHEIT!’ (Freedom!).

Those of us in the West who were not Reaganite Cold War warriors shouldn’t dismiss the fact that what we regarded as basic freedoms e.g. the right to travel abroad if/when we wanted to, were denied to others.

That said, while it is undoubtedly true that some important things were gained by the changes of 1989 other important things were lost as well, in both east and west. The citizens of the former GDR can travel anywhere and the Stasi is long gone, but economically, everyday life is arguably much more of a struggle than it was forty years ago when the state provided almost everything. In 2017, Reuters reported that the lagging economy in the east of Germany risked stoking radicalism. In 2018 unemployment in the east was eight percent.

But in the former West Germany too there’s been regression since 1989. It was reported last year that the share of Germans at risk of falling into poverty had risen to an all-time high with poverty looming for almost one in six citizens. Income inequalities have widened across the country.

When we look at what has happened across western Europe since 1989, it’s hard to argue that the existence of a rival economic system – communism – (for whatever faults it had), did not lead to a better deal for the majority in the non-communist countries. With no alternative (to paraphrase Margaret Thatcher), the capitalist elites haven’t felt the need to give us any more goodies than they need to. The fall of communism and the consequential move away from fairer, more collectivist/mixed economy systems has ushered in a new period of much greedier, profit-obsessed, turbo-capitalism. That‘s led to a situation when the global one percent now own more than the rest of us combined.

A further point to ponder is would we have had the neocon-instigated regime-change wars, without the changes of 1989? When you consider the number of people killed in these conflicts, and the global instability caused by them – which includes a refugee crisis of biblical proportions – it certainly makes you think.

Op-Ed by Neil Clark

Interesting perspective. Sometimes we let the media think for ourselves and we repeat what is said without much individual analysis

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit