Since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020, media platforms have become a battleground between the adherents of two diametrically opposed dogmas: germ theory and terrain theory. According to one of these philosophies many of the diseases that afflict us are contagions caused by microscopic pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria, which prey upon us and other animals. According to the other there are no such pathogens: disease is the body’s response to unhealthy living.

In this article I am going to take a step back from the battlefield and assess the contradictory evidence for and against each of these doctrines. When the pandemic began I was not aware of terrain theory and did not even know that germ theory had its critics. That has all changed. Over the past few years, the more I have researched the subject the more I have become predisposed to reject germ theory in favour of the alternative. But there remain many credible thinkers in the truth community who have continued to espouse the germ theory and its underlying idea of contagion. Vernon Coleman, for example, has not budged on this question, and has offered cogent reasons for maintaining his stance—as we saw in the last article.

In 1120 the French philosopher and theologian Pierre Abélard wrote a treatise with the title Sic et Non, Late Latin for Yes and No. In this work Abélard presented evidence from the writings of the Church Fathers for and against 158 dogmas of Christian theology. He believed that these contradictory passages could ultimately be reconciled. In this article we will take a leaf out of Abélard’s book and list some of the pros and cons for and against germ theory and terrain theory. But whether these contradictions will ever be reconciled I cannot say.

Contagion

The transmission of disease from one individual to another makes no sense if terrain theory is correct. But contagion is a fact of life—isn’t it? Today it is commonly accepted that infectious diseases such as influenza and the common cold spread like wildfire through communities, passing with ease from the sick to the healthy.

Throughout history humanity has suffered from plagues and pestilences that have spread from person to person, carrying off countless victims who were otherwise healthy. The Justinian Plagues were instrumental in destroying the classical civilization of the Roman Empire and ushering in the Dark Ages. The Black Death wiped out up to half of the population of Eurasia in the middle of the 14th century. Over the course of the following three or four centuries regular outbreaks of the Plague devastated the continent’s cities. How can anyone seriously dispute the reality of contagion in the face of these historical facts?

On the other hand, there are well-documented cases in which researchers attempted to prove the contagiousness of infectious diseases and failed. The two best-known cases tried to demonstrate the infectiousness of the so-called Spanish Flu of 1918-1919:

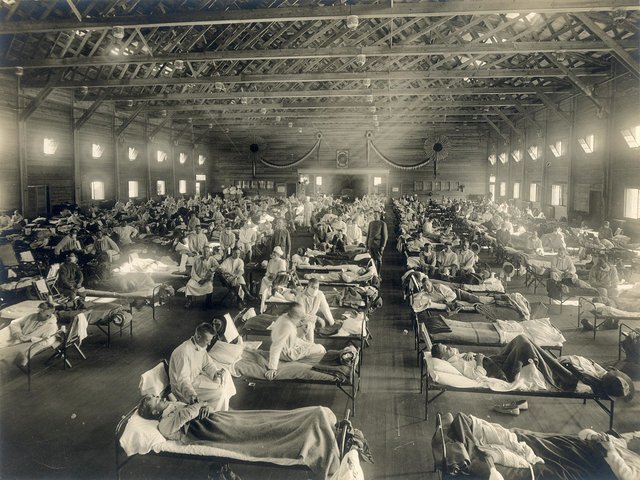

Perhaps the most interesting epidemiological studies conducted during the 1918–1919 pandemic were the human experiments conducted by the Public Health Service and the U.S. Navy under the supervision of Milton Rosenau on Gallops Island, the quarantine station in Boston Harbor, and on Angel Island, its counterpart in San Francisco. The experiment began with 100 volunteers from the Navy who had no history of influenza. Rosenau was the first to report on the experiments conducted at Gallops Island in November and December 1918. His first volunteers received first one strain and then several strains of Pfeiffer’s bacillus by spray and swab into their noses and throats and then into their eyes. When that procedure failed to produce disease, others were inoculated with mixtures of other organisms isolated from the throats and noses of influenza patients. Next, some volunteers received injections of blood from influenza patients. Finally, 13 of the volunteers were taken into an influenza ward and exposed to 10 influenza patients each. Each volunteer was to shake hands with each patient, to talk with him at close range, and to permit him to cough directly into his face. None of the volunteers in these experiments developed influenza. Rosenau was clearly puzzled, and he cautioned against drawing conclusions from negative results. He ended his article in JAMA with a telling acknowledgement: “We entered the outbreak with a notion that we knew the cause of the disease, and were quite sure we knew how it was transmitted from person to person. Perhaps, if we have learned anything, it is that we are not quite sure what we know about the disease.”

The research conducted at Angel Island and that continued in early 1919 in Boston broadened this research by inoculating with the Mathers streptococcus and by including a search for filter-passing agents, but it produced similar negative results. It seemed that what was acknowledged to be one of the most contagious of communicable diseases could not be transferred under experimental conditions.” (Eyler 35)

The experiments conducted in Boston and San Francisco in 1918-1919 were just two of many trials that attempted and failed to transmit an alleged virus to humans in both natural and experimental settings. Many other studies conducted throughout the early 20th century came to similar conclusions. In 1921 Sara E Branham and Ivan C Hall from the Department of Hygiene and Bacteriology at the University of Chicago tried to isolate and culture viruses from cases of influenza and the common cold:

These experiments offer no evidence in support of the theory that the cause of either common colds or influenza is a filtrable virus. In attempting to cultivate filtrable viruses from the nasopharyngeal secretions in colds and influenza, no bodies were found in the “cultures” which could not be found also in those from normal persons, in controls in all simple mediums examined, and on blank slides.

It is recognized that negative experiments, limited to the attempted cultivation of a filtrable virus, and including no attempts to reproduce the disease in animals, do not offer conclusive evidence that such a virus is not involved.

No conclusions can be drawn concerning influenza, on account of the few cases examined, together with the fact that samples of such were not collected during the earliest stages of the disease. However, the uniformly negative results obtained with a large and representative number of colds are not without significance. (Branham & Hall 148-149)

Hospital-Acquired Infection

It has also been argued that if contagion were as common as is generally believed, then doctors, nurses and other hospital staff, who are exposed to multiple infectious diseases on a daily basis, ought to have statistically shorter lifespans than other people. In fact, the opposite is the case. On average, doctors live longer than non-doctors:

Among both U.S. white and black men, physicians were, on average, older when they died, (73.0 years for white and 68.7 for black) than were lawyers (72.3 and 62.0), all examined professionals (70.9 and 65.3), and all men (70.3 and 63.6). The top ten causes of death for white male physicians were essentially the same as those of the general population, although they were more likely to die from cerebrovascular disease, accidents, and suicide, and less likely to die from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia/influenza, or liver disease than were other professional white men. (Frank et al 155)

There is also no evidence that hospital staff suffer from more infections than do members of the general public. But should they not be suffering constantly from multiple infections if contagion is so prevalent?

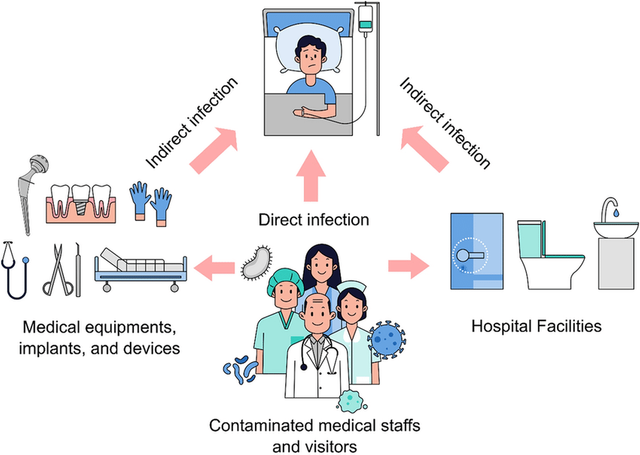

On the other hand, isn’t hospital-acquired infection (HAI) a well-established fact?

In 2002, the estimated number of HAIs in U.S. hospitals, adjusted to include federal facilities, was approximately 1.7 million: 33,269 HAIs among newborns in high-risk nurseries, 19,059 among newborns in well-baby nurseries, 417,946 among adults and children in ICUs, and 1,266,851 among adults and children outside of ICUs. The estimated deaths associated with HAIs in U.S. hospitals were 98,987: of these, 35,967 were for pneumonia, 30,665 for bloodstream infections, 13,088 for urinary tract infections, 8,205 for surgical site infections, and 11,062 for infections of other sites. (Klevens et al 160)

The vast majority of these deaths are patients who have been hospitalized for other reasons. Why are there so few deaths among hospital staff? Could it be because their terrains are healthy, whereas patients admitted to hospital have compromised terrains?

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are chemical substances that are toxic to specific forms of bacteria. Ever since the serendipitous discovery of the world’s first antibiotic, penicillin, the use of antibiotics has revolutionized the treatment of many infectious diseases. They have also allowed surgery to be carried out in relatively safe conditions. Countless lives have been saved by antibiotics. This is not in dispute.

The only argument I can come up with in support of terrain theory is to concede that certain types of bacteria can cause disease and even death if they succeed in penetrating our bodies’ defences and infecting our healthy tissues. Antibiotics can kill these infections, ending disease and saving lives. But these bacteria are not pathogens. They have not been engineered by nature and evolution to invade our tissues and kill us. It is only in exceptional circumstances—during warfare, for example, or surgery—that these microbes are inadvertently introduced to our healthy tissues. They do not want to be there. They are just as much the victims of circumstance as is the patient.

Flu Season

Proponents of terrain theory tell us that when a person comes down with influenza, their body is going through a process of detoxification. If that is true, then why is there a specific time of year when flu cases are rampant among the population? Why do we have a flu season at all? Don’t people in the west eat garbage and lead unhealthy lives throughout the year?

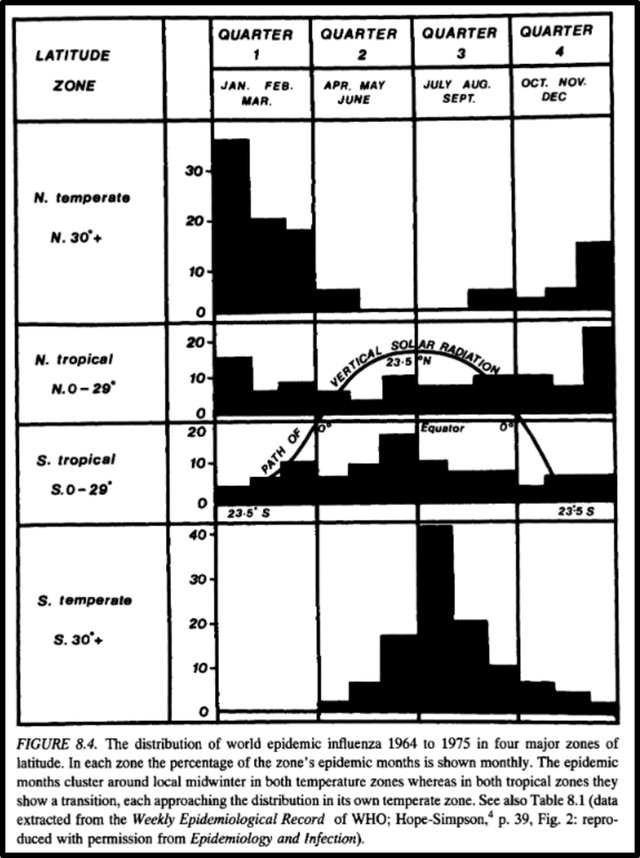

In the northern hemisphere, flu season occurs around January. In the southern hemisphere it occurs about six months later, during the southern winter. But there is no obvious flu season in the tropics. Does any of this make sense in either of the two models we are considering?

And what is the difference between influenza and the common cold? Why does one person’s body detox itself through the flu while another person’s body detoxes itself through the common cold? None of this makes any sense to me. Clearly, there is more going on here than simple detoxification.

Have proponents of terrain theory ever collected any of these toxins as they were being expelled from the body? What are these toxins?

How does having an inflamed throat detox the body?

Germ theory, too, has its difficulties in explaining the seasonality of influenza. The British general practitioner Robert Edgar Hope-Simpson devoted about sixty years of his life to this problem. In The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza, his 1992 book on the subject, he developed a highly implausible model to try and explain away numerous anomalies that beset the traditional model of person-to-person transmission. It has not attracted much support from either side of the debate. Hope-Simpson has had to perform some mental gymnastics to account for the anomalies while at the same time preserving his belief in germ theory. I hope to take a closer look at Hope-Simpson’s theories in a later article.

Tuberculosis

According to germ theory, tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the pathogenic microbe Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is estimated that as much as one quarter of the human race have tuberculosis—though many of these have latent rather than active TB, and so are not thought to be contagious. In 2020 an estimated 10 million people worldwide developed active TB. More than half the diagnosed cases of TB occur in India, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Nigeria and Bangladesh. In many Asian and African countries as many as 80% of the population test positive for TB, whereas the figure in the developed world is about 5-10%.

Active tuberculosis is highly infectious, spreading from person to person through airborne transmission. If TB is endemic in many developed countries, why is there not a global pandemic of TB? The seven countries listed in the previous paragraph have not been quarantined. Thousands of people from these countries travel to and from the developed world on a daily basis, and thousands of people from the developed world visit countries where TB is endemic. Why, then, has TB not spread all over the world, causing a global pandemic—like, say, COVID-19?

The most curious thing about tuberculosis is that in 90% of the cases which test positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis the patient is asymptomatic—that is to say, perfectly healthy. This is actually true of many bacterial infections:

This ridiculous concept of healthy carriers of pathogenic entities extends far beyond “viruses” and the few discovered instances credited to Koch. The asymptomatic carrier is a major aspect of many of the diseases claimed to be caused by bacteria. In fact, the case could be made that none of the major bacterial diseases have ever fulfilled the very first of Koch’s Postulates as they all result in a majority of asymptomatic cases. Thus Koch’s Postulates, as originally laid forth, have never been satisfied for bacteria either. Presented below are sources detailing 10 major bacterial diseases [tuberculosis, Salmonella,Heliobacter pylori, cholera, syphilis, gonorrhea, pertussis, tetanus, Escherichia coli, and chlamydia, ] which are made up of mostly asymptomatic carriers. (ViroLIEgy)

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Sara E Branham & Ivan C Hall, Influenza Studies III: Attempts to Cultivate Filtrable Viruses from Cases of Influenza and Common Colds, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 28, Number 2, Pages 143-149, Oxford University Press, Oxford (1921)

- John M Eyler, The State of Science, Microbiology, and Vaccines Circa 1918, Public Health Report 2010, Volume 125 (Supplement 3), Pages 27-36, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland (2010)

- Erica Frank, Holly Biola, Carol A Burnett, Mortality Rates and Causes among U.S. Physicians, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Volume 19, Issue 3, Pages 155-159, (2013)

- Robert Edgar Hope-Simpson, The Transmission of Epidemic Influenza, Springer Science+Business Media, New York (1992)

- R Monina Klevens et al, Estimating Health Care-Associated Infections and Deaths in U.S. Hospitals, 2002, Public Health Reports, Volume 122, Number 2, Pages 160-166, SAGE Publishing, Newbury Park, California (2007)

- Milton Joseph Rosenau, Experiments to Determine Mode of Spread of Influenza, Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 73, Number 5, Pages 311-313, Chicago (1919)

- Milton Joseph Rosenau et al, I Experiments upon Volunteers to Determine the Cause and Mode of Spread of Influenza, Boston, November and December, 1918, II Experiments upon Volunteers to Determine the Cause and Mode of Spread of Influenza, San Francisco, November and December, 1918, III Experiments upon Volunteers to Determine the Cause and Mode of Spread of Influenza, Boston, February and March, 1919, Treasury Department, United States Public Health Service, Hygienic Laboratory—Bulletin Number 123, Pages 5-41, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC (1921)

Image Credits

- COVID-19 Poster: © 2021 Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Fair Use

- Pierre Abélard: Abélard et Héloïse, Anonymous artist (14th century), Le Roman de la Rose, Condé Museum, Château de Chantilly, Chantilly

- Milton J Rosenau: National Institutes of Health, United States Government, Public Domain

- Soldiers with Spanish Flu at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas: Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Silver Spring, Maryland, Public Domain

- Sara Elizabeth Branham: National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, United States Department of Health and Human Service, Public Domain

- Hospital-Acquired Infection: © Vinda Puspasari, Aga Ridhova, Angga Hermawan & Muhamad Ikhlasul Amal (designers), Fair Use

- La Miseria: Cristóbal Rojas (artist), National Art Gallery, Caracas, Venezuela, Public Domain

Online Resources