Urban children are playing in toxic dirt

Decades of build-up have left invisible mountains of lead in America’s urban centers, including Santa Ana, California. A ThinkProgress investigation.

Artwork by Diana Ofosu

During a routine visit to the doctor several years ago, Maria Vasquez was given the alarming news that her youngest son, Ulises, had lead in his blood, and one of the first questions the concerned mother asked the pediatrician was about the possible source of the lead.

Ulises’ elevated lead tests mirrored those of Vasquez’s eldest son, Benjamin, who had tested positive for lead a few years earlier while living in the same home where Vasquez, her husband and two young boys rented a room for three years.

Of all the possible sources that might be poisoning her children, Vasquez never imagined that the culprit might be in her own backyard.

“The doctor said sometimes houses are old, or children eat old paint chips, or when people cook in ceramic pots or the kids eat candy with lead, they get lead in their blood,” Vasquez told ThinkProgress in Spanish.

But this didn’t seem right to Vasquez, a stay-at-home mom and Mexican native who said her children hardly eat candy. In fact, she said she avoids Mexican candy and doesn’t cook in Mexican ceramic pots because she was aware of the potential dangers of lead in both.

However, Ulises, now 5, loved to play outdoors with his 8-year-old brother, and the two could spend hours digging in a long strip of dirt in their tiny backyard playing make-believe with his action figures.

Many families with young children live in this Santa Ana neighborhood between Cedar and Evergreen streets, where ThinkProgress found soil lead levels as high as 4,094 parts per million, which is more than 50 times higher than the hazard level set for play areas in residential soils by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

Vasquez initially had not allowed Benjamin to play in any dirt.

“Don’t be so fussy,” Vasquez’s husband would tell her, reminding her that in Mexico where both of them were raised, children would throw themselves in the mud, play in the dirt, and roll on the ground.

But Vasquez was right to be concerned — the source of the lead in her sons’ blood was likely her own backyard.

A series of soil tests conducted on the family’s former rental property by a ThinkProgress reporter showed lead levels that were as much as ten times higher than what the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) considers dangerous for children.

That home, which the Vasquez family left more than two years ago, is in Santa Ana, Ca. where the number of children tested with dangerous levels of lead in their blood exceeds the state average by 64 percent. A ThinkProgress investigation found hazardous levels of lead in the soil in almost a quarter of more than 1,000 soil samples tested in homes and public spaces throughout the city.

For years, the state’s childhood blood lead level data has shown that Santa Ana has a greater number of lead poisoned children compared with children in other Orange County cities, but the Orange County Health Care Agency (OCHCA) cannot explain why and has not mapped where hot spots of contamination may exist so parents can avoid them. County data show that out of 16 environmental investigations conducted from 2013 to 2015 by the Health Care Agency, only three were done in Santa Ana.

Instead, the agency has relied on public awareness campaigns and outreach that do not emphasize soil exposure, even though the state Department of Public Health says dust and soil contaminated by leaded gasoline is the most significant environmental lead contaminant in the state, and the dominant source of lead exposure to children in California due to decades of leaded gasoline use that deposited particles of lead in the soil.

The source of the lead in her sons’ blood was likely her own backyard.

In interviews, county health care agency officials said the county has not been able to draw any conclusions about possible source trends from the environmental investigations the agency has conducted in the past. They say this is primarily because there aren’t many such cases to analyze.

Legal advocates and public health experts also say that state and local health care agencies are using standards that aren’t stringent enough to protect children from lead exposure.

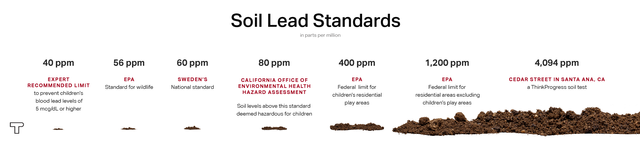

For example, when the health care agency conducts an environmental investigation in a child’s home and tests the soil, per state regulations, only soil that has 400 parts per million (ppm) or more in children’s play areas is considered lead-contaminated soil and could trigger further investigation. The state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has deemed that level too dangerous for children and recommends further evaluations at 80 ppm.

The OEHHA standard is just a recommendation, not a regulatory standard, so the state Department of Public Health’s policies on childhood lead intervention are based on the higher threshold in the state’s lead soil regulation.

The state regulation aligns with the 400 ppm standard set by the federal Environmental Protection Agency in 2000.

That year, the EPA acknowledged that lead poisoning is “the number one environmental health threat American children face.”

Lead-contaminated soil: A uniquely urban problem

“The major source of exposure to most children is from the soil environment because the accumulation of lead has been so enormous, and it’s a reservoir of very large amounts of lead,” said Howard Mielke of Tulane University’s School of Medicine, one of the nation’s top experts on lead soil contamination.

Decades of gasoline lead emissions have resulted in large deposits of lead particles that remain in the soil today, particularly in poor, urban areas with a history of high-density traffic flow.

The result of that contamination, he said, is that “we keep seeing… very serious behavioral, learning, and morbidity types of problems.”

While he searches for a stick to repair his toy, a boy handles dirt in a northwest Santa Ana neighborhood where ThinkProgress found elevated levels of lead in the soil. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

Researchers have found elevated blood lead levels can lead to increased aggression, lack of impulse control, hyperactivity, inability to focus, inattention, and delinquent behaviors. And as more scientific evidence emerges on the neurotoxic effects of lead on the developing brain, experts have emphasized that prevention is the key to eliminating the threat of lead exposure.

Lead emitted as an aerosol into the environment accumulates in soils and can remain there for hundreds of years, according to Mielke and other experts. His research on lead in New Orleans has shown that at least five to 10 times more lead dust comes from lead gasoline additives compared to leaded paint, with the highest concentrations of dust found in the high traffic flow areas of the inner city.

Another study conducted on airborne lead in California’s South Coast Air Basin, which includes Orange County, found that lead particles deposited in the soil during the years of leaded gasoline use continued to pollute the air, even after lead was banned from gasoline, due to the resuspension of these particles into the air.

Diana Ofosu / ThinkProgress

The 2005 study by Carnegie Mellon University found that this resuspension accounted for a majority of the lead aerosols generated annually compared to conventional industrial sources, which accounted for 13 percent of the lead aerosols.

The researchers concluded that “resuspension, although an insignificant source of airborne lead during the era of leaded fuel, became a principal source in the [South Coast Air Basin] as lead emissions from vehicles declined. The results of the resuspension model further suggest that soil lead levels will remain elevated for many decades, in which case resuspension will remain a major source well into the future.”

“We’re talking about children and we’re talking about the future of society,” Mielke said. “You really have to err on the side of caution when you’re dealing with an issue that so severely affects children, and there’s no way around that.”

Research shows that lead particles deposited in the soil… continued to pollute the air, even after lead was banned from gasoline.

Children, in essence, are being used as biological indicators of lead-contaminated housing because society has not been willing to invest in efforts to remove the lead from children’s environments, said Bruce Lanphear, an epidemiologist and professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University in Canada.

Lanphear’s research has focused on fetal and early childhood exposure to lead and other environmental neurotoxins. He has found that children with low to moderate blood lead levels experience the most IQ point loss.

“To the extent that a child has been chronically exposed over the first two years of their life, and then you remove them…you’ve really failed to protect that child,” said Lanphear.

Finding lead in Santa Ana’s soil

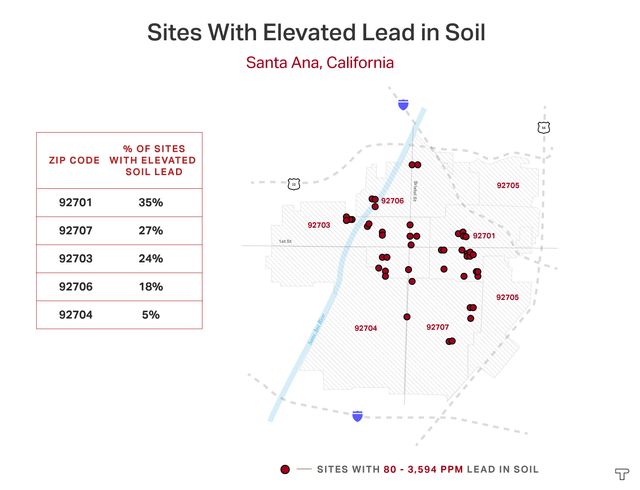

As part of its investigation into lead contamination in Santa Ana, ThinkProgress conducted 1,023 soil tests, primarily in residential yards, over a six-month period concluding in May 2016.

ThinkProgress tested the soil in about a dozen Santa Ana residential neighborhoods across six zip codes. The vast majority of the tests were done on soil in yards where children often play. Others were conducted in public spaces such as street-side right of ways, playgrounds, parks, and bike trails.

Among the samples tested, 24 percent surpassed the level that the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) deems “safe”—80 parts per million.

Diana Ofosu / ThinkProgress

In 2009, the OEHHA announced that it would reduce the agency’s soil screening level for lead from 150 ppm to 80 ppm, a decision they took after reviewing the latest research on lead’s neurological impact on the developing brains of children.

The agency determined that soil concentrations above 80 ppm could increase a child’s blood lead level by up to 1 microgram per deciliter (mcg/dL)and result in a loss of one IQ point.

In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that no level of lead in children is safe and recommended public health intervention for children under 6 with blood lead levels above 5 mcg/dL, a decrease from the previous screening action guideline of 10 mcg/dL.

Nationally, blood lead concentrations in U.S. children have dropped dramatically over the past three decades, but lead continues to plague communities across the country. There are about half a million young children in the United States with blood lead levels above five mcg/dL, according to) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And the number of children with lower, but still harmful levels above 1 mcg/dL is much higher at more than 12 million children nationwide, according to 2010 figures cited in a CDC statement.

But California researchers estimate the numbers of lead-burdened children are actually much higher due to the endemic undercounting and underreporting of blood lead levels in states across the country, including California.

In April, the Public Health Institute in Oakland released a national study showing that states are failing to adequately test children’s blood for lead exposure, leaving vast numbers of children undiagnosed. In California, the study estimates, only 37% of children with elevated blood lead levels were identified.

A 2-year-old girl plays in her front yard in northwest Santa Ana where ThinkProgress found hazardous levels of lead in the soil. Young children are especially vulnerable to lead because of the toxin’s impact on the developing brain. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

Experts estimate that nationally between 22 to 33 percent of 1–2 year-old children have their blood lead levels tested.

At its peak in 2010, California tested 20.7 percent of children under the age of 6 years statewide. This is according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dataset of children under six years who were tested in California from 1997 to 2014. That age group is the most vulnerable to the neurotoxin’s effects on the brain, and are the most likely to ingest or inhale the lead particles. [The CDC did not have complete data for California from 2012 through 2015.]

Citywide, the percentage of Santa Ana children under the age of 21 with blood lead levels at or higher than 4.5 mcg/dL was 64 percent higher than the state average in 2012, according to the most current publicly available California Department of Public Health data. That year, 3.15 percent (328 children) of Santa Ana children tested had elevated levels, compared to the state average of 1.92 percent.

https://public.tableau.com/views/SuantaAnaBBL/SantaAnaBBL?:embed=true&:toolbar=no&:display_count=no

Santa Ana has topped the list of cities in the county for children with elevated lead levels for a decade, according to state and county data. In 2015, the state reported 246 Santa Ana children with actionable levels, more than twice as many as Anaheim, the next-highest city on the list of Orange County cities, according to data the California Department of Public Health provided to ThinkProgress.

Most other Orange County cities reported far fewer children with actionable levels, ranging from one child in San Clemente to nine children in Brea.

Confusing guidelines that fail to protect children

California guidelines say that only bare soil containing 400 parts per million of lead or more in children’s play areas is considered lead-contaminated soil and would require further investigation. But a state Department of Public Health spokesman told ThinkProgress in an email that lower levels “may still be considered contributing potential sources of lead exposure to a child…”

California, like other states, follows the benchmarks set in 2000 by the U.S. EPA’s lead soil guidelines: 400 ppm for bare soil in children’s play areas, and 1,200 in the remainder of the yard.

In contrast, the EPA’s level for wildlife mammals is just 56 ppm.

Diana Ofosu / ThinkProgress

In California, the lower threshold of 80 ppm for children is for informational and not regulatory purposes, said David Siegel, acting assistant deputy director for scientific affairs at the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

However, Howard Mielke said that even the OEHHA’s screening level of 80 ppm is too high to protect children and was originally set to prevent children’s blood lead levels from reaching 10 mcg/dL. Given the CDC’s current reference value of 5 mcg/dL for children under six years, soil standards should be reduced by at least half of 80 ppm in order to protect children, said Mielke. He noted that the federal and California soil standard of 400 ppm has no margin of safety for children.

Countries such as Norway, Sweden, and Germany have lead soil standards that are more stringent out of concern for childhood lead exposure—Sweden, for example, sets its lead soil guideline at 50 ppm in cities.

“You really have to have very clean soil in order to protect children, and this is the dilemma we have. We have guidelines that don’t have a margin of safety to protect children,” said Mielke.

A child plays in this east Santa Ana yard where soil lead levels were more than double the level considered dangerous for children by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

How lead polluted our soil

The roots of soil-based lead contamination can be traced back to the 1920s, when tetraethyl lead was originally added to gasoline to keep engines running smoothly. At the time, health experts, including Yale University physiology professor Yandell Henderson warned the federal government that lead exhaust from cars would cause widespread chronic lead poisoning in urban centers.

Lead exposure is the greatest health menace which ever faced the public, a 1925 New York Times article quoted Henderson as saying during a public speech in which he criticized the use of leaded gasoline and the government’s failure to properly investigate the issue.

Meanwhile, manufacturers of the lead additive claimed that leaded gasoline was perfectly safe.

In the 1950s, the use of lead additives in gasoline began to increase due to growing automobile sales, the expansion of the U.S. highway system, and the decline of public rail transit systems, according to Mielke’s research.

It was only after the passage of the federal Clean Air Act in 1970 that the automobile industry, compelled to decrease sulfur emissions to reduce smog, introduced a catalytic converter, which required lead-free gasoline, according to the book Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America’s Children by historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner. This resulted in a gradual phase-down of lead additives starting in the mid-1970s.

The EPA issued the first lead emissions reductions standards in 1973. Then on Jan. 1, 1986, the EPA ordered the largest phase-down of leaded gasoline, which was followed by the federal ban on leaded gasoline for on-road vehicles starting Jan. 1, 1996.

However, even today, a little known federal regulation allows unleaded gasoline to contain trace amounts of the toxic metal, which experts say contributes to already contaminated soil, and harms children, particularly those living in traffic-congested urban areas.

Further, the environmental ramifications of the neurotoxicant continue to be felt today because lead does not degrade.

“There’s a widespread perception that the lead problem has been solved because it’s no longer in gasoline or in paint,” said Harvard University’s David Bellinger, who is president of the International Society for Children’s Health and the Environment. “But there’s not very much recognition that we have a lot of legacy lead that’s left from those prior uses over decades and that is still impacting children.”

A pollutant with a racial gap

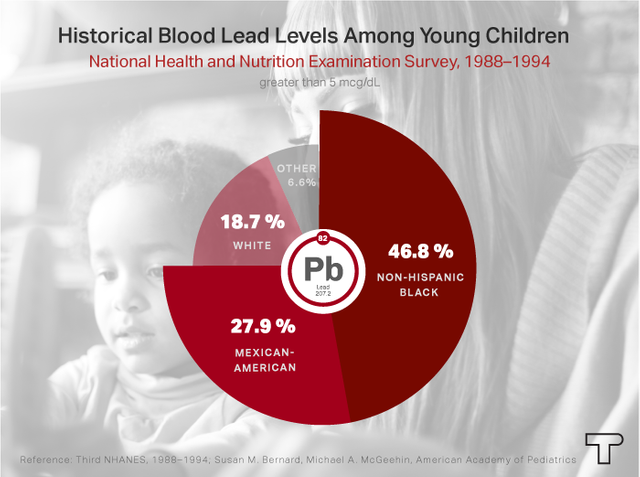

Historically, children of color, particularly African American children, were disproportionately impacted by lead. Data from one national health survey conducted from 1988–1994 showed that 46.8 percent of non-Latino black children, and 27.9 percent of Mexican-American children, had elevated blood lead levels. Just 18.7 percent of non-Latino white children had elevated levels.

A 2003 CDC report on U.S. children with elevated blood lead levels (greater or equal to 10 micrograms per deciliter) found that among those tested whose race and ethnicity was known, 83 percent were children of color, and of those, a majority were non-Latino black children (60 percent).

Diana Ofosu / ThinkProgress

Although the percentage of children with elevated blood levels have dropped significantly over the past few decades, especially among African American children, researchers have found that racial and economic disparities persist today largely due to differences in environmental exposure.

Today, blood lead levels above 10 mcg/dL remain much more common among minority children, low-income families, and children living in older homes, according to Prof. Bellinger, who has researched the effects of chemical exposures on children’s developing brains for nearly four decades.

Researchers in a recently published study of Rhode Island children confirmed results similar to those of previous national studies: significant blood lead level disparities by race and income. The average preschool child’s blood lead level in the study was 3.8 mcg/dL, which aligned closely with the average level for white children of 3.4 mcg/dL. By comparison, African American and Latino children had levels of 5.3 mcg/dL and 4.5 mcg/dL respectively.

The study also found that African American and Latino lead-burdened children were more likely be suspended or detained in juvenile hall than their white counterparts. African American children were two-and-a-half times more likely to get suspended, and four times more likely to be placed in juvenile detention than white classmates.

Professor Howard Mielke of Tulane University’s School of Medicine is one of the nation’s top experts on soil lead contamination. He continues his work to protect children from lead exposure in New Orleans with his research associate, Eric Powell, (left), after visiting a local childcare center. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

The racial disparity tends to be geographic, as well: Neighborhoods where lead poisoning is prevalent are disproportionately African American or low income. Researchers have found that these areas are typically found in urban centers that are racially segregated, near current or past lead emission sources, and have older housing, according to one 2016 report on the racial gap on childhood blood lead levels in Detroit.

Poor and disadvantaged communities also tend to cluster geographically, resulting in “neighborhoods with higher exposure to environmental toxins such as lead and less access to resources that directly mitigate the exposure…” concluded another report titled “Inequitable Chronic Lead Exposure” published in 2016.

Mielke has found that after decades of lead contamination from the use of lead-based paint, smelters (which tend to cluster in areas that impact low-income communities), and lead in gasoline, the build-up of lead in America’s cities has created invisible mountains of lead in our urban cores.

“There are a lot of pathways of exposure and they seem to add up to the most for poor children, mostly of color,” Bellinger said.

Diana Ofosu / ThinkProgress

So even though national statistics showing decreases in childhood blood concentrations are encouraging, experts like the University of Cincinnati’s Kim Dietrich said that the reality is in urban communities such as Cincinnati where he’s focused his research, too many children are still being exposed.

“We’re still hospitalizing half a dozen kids every month for lead poisoning,” said Dietrich, director of epidemiology and biostatistics at the university’s College of Medicine. “If we were hospitalizing children for some other disease, we’d have a telethon going on here.”

Where are the danger zones? Officials don’t know

Despite the mounting evidence of the widespread dangers of soil-based lead, there was a muted reaction among Orange County public health officials to ThinkProgress’ soil test findings.

David Nuñez, the Orange County Health Care Agency’s family health medical director, said his chief concern would be whether children are playing in the soil, eating the soil, or putting their hands in their mouths, which would put them at risk for ingesting the lead particles.

“So just having [lead] in the soil doesn’t necessarily mean that it is a risk,” said Nuñez.

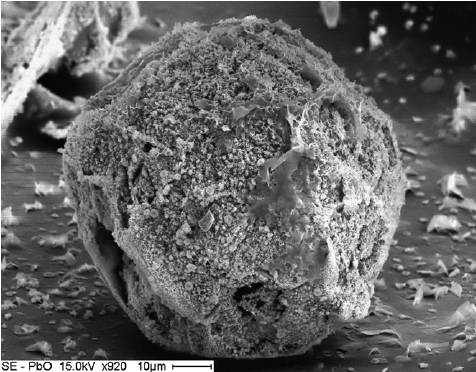

an individual lead oxide particle in sand CREDIT: Institute of Terrestrial Ecology

Nuñez is correct. But Mielke, the Tulane University lead soil expert, has found that even if lead-contaminated soil is left undisturbed, it still poses a risk for children, particularly in the summer and fall. During hot, dry weather, soil dust is re-circulated into the atmosphere.

“The dust is extremely fine particles — it’s mere nanoparticles — and that becomes very potent,” Mielke said. “It goes right through the cell wall into the bloodstream.”

Mielke demonstrates this using a one-gram packet of Sweet’N Low, which he opens, and blows out of his palm.

“That’s one gram. What we’re worried about is six micrograms, so that’s six millionths of what’s in that Sweet’N Low packet,” said Mielke.

“If we were hospitalizing [this many] children for some other disease, we’d have a telethon going on here.”

At the state level, the responsibility for both protecting children from lead poisoning, and treating those who suffer from it, falls to the California Department of Public Health’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Branch.

The agency contracts—and provides $16 million annually to—local health care agencies to investigate lead sources, case-manage lead poisoned children, and investigate and remove lead hazards in areas where lead-exposed or at-risk children live.

But the state’s blood lead level data is not current (the latest data set is from 2012), isn’t geographically mapped, and doesn’t identify blood lead measurements below 4.5 micrograms per deciliter, according to documents reviewed by ThinkProgress. Experts know that low-level lead exposure (resulting in blood lead concentrations below 5 mcg/dL) affect not only a child’s intellectual and academic abilities, but are also a risk factor for higher rates of neurobehavioral disorders.

Last year, the agency requested approval from the state legislature to spend $500,000 to map locations of lead exposure and lead-poisoned children over the next two years. So far the legislature has approved $180,000 of that request for the current fiscal year.

With this effort, state and county officials expect to identify more lead-exposed children, due in part to the state Health Department’s lower threshold for blood lead levels that require public health intervention. But these efforts come decades after environmental and legal advocates, and even the state auditor, have called on the Department of Public Health to more aggressively pinpoint lead sources in California.

Lead poisoning cases among children statewide are expected to increase from about 200 children annually to 600, according to the budget request. Eighty percent of these cases are Latino children and 90 percent are beneficiaries of Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, which provides state and federally-funded health care services for low-income residents.

A 2-year-old girl runs carefree in her northwest Santa Ana home where ThinkProgress found dangerous levels of lead in the yard’s soil. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

Under its contract with the state, Orange County’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program receives $965,000 annually to treat lead burdened children and to prevent lead poisoning.

But county officials appear to be largely in the dark when it comes to pinpointing specifically where and how OC children are being lead-poisoned. The county has not used the publicly available state blood lead level data from previous years (2007 to 2012) to geographically map hot spots for lead exposure in Santa Ana or the county. This is despite the fact that the CDC has stated that even low lead exposure levels can be used to identify at-risk children and geographic hot spots.

“I can speak generally to the fact that the sources that have been identified as concerning have certainly been found in Orange County, including paint, pottery, the costume jewelry, traditional remedies, and the candies, as well as some occupational exposures, have all been noted, so that full range of exposures continues to be something that we focus on,” Nuñez said.

On a section of its website that outlines lead-exposure sources, the OCHCA makes no mention of soil-based lead exposure. The agency also said Santa Ana and Anaheim are the top two cities where the OCHCA focuses its community awareness efforts, but officials couldn’t narrow down the highest-risk lead sources for children based on previous test data.

“I would say the challenge is to maintain continued awareness in the community that lead remains a serious and potential environmental exposure of concern in California and in Orange County, and so it’s up to us to continue to maintain high vigilance particularly amongst our healthcare providers that serve that age group,” said Nuñez.

In 2012, the year the CDC declared that no level of lead in children is safe, Congress slashed the agency’s Healthy Homes and Lead Poisoning Prevention Program funding by 93 percent: from $29.2 million to $2 million, according CDC spokeswoman Susan J. McBreairty.

This eliminated the CDC’s ability to fund state and local lead poisoning prevention programs, including support to gather blood lead surveillance data. When ThinkProgress inquired why childhood blood lead level data for California is missing for 2012 and 2013 on the CDC’s website, McBreairty explained that the funding cuts prevented some states from providing that data.

In fiscal year 2016, Congress appropriated $17 million in funding for the CDC’s lead program, and according to McBreairty, the agency now funds lead surveillance for 35 state and local health departments.

However, states must apply to the CDC to receive this money, which can be up to $500,000 per year. And California has not done so, according to CDC officials. The California Department of Public Health confirmed it didn’t apply in 2014 given the amount of the award and the additional administrative requirements and costs associated with the funding.

“CDC funding seemed more appropriate for other [Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention] Programs where the funds are sometimes the major source of support,” said a spokesman for the agency, which had a budget of $27 million in the 2014–15 fiscal year.

Screening for lead—and focusing on preventing exposure

Studies have consistently shown that despite federal policies that require children on Medicaid to be screened for lead, many are not. In 1999, a U.S. General Accounting Office report to Congress found that nearly two-thirds of young children in or targeted by federal health care programs had not been screened for lead.

A decade later, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found that only about 66 percent of children enrolled in Medicaid had received a blood test in 2008–2009 as required at ages 12 and 24 months.

Concerned that current policies and practices are falling short of what’s needed to prevent childhood lead exposure, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement last July recommending primary prevention as the focus of public health policies.

“The primary prevention approach contrasts with practices and policies that too often have relied predominantly on detection of lead exposure only after children develop elevated blood lead concentrations,” the report stated.

Mielke agreed: By approaching childhood lead poisoning one child at a time, he said, communities are destined to fail because this approach doesn’t address lead contamination as the community-wide problem that it is.

For example, the CDC recommends parent education on lead prevention, and this often includes how to properly clean a house to remove contaminated dust. But studies have shown that cleaning doesn’t impact children’s blood lead levels, said Mielke.

Another issue Mielke points to is that while decades of research have shown how extremely sensitive children are to lead in their environment, public policies continue to address lead exposure by measuring lead in children versus lead in the environment.

“It’s a lot easier to measure the amount of lead in soil than it is to measure the amount of lead in the blood. The soils don’t squirm, they don’t cry. You can easily get a soil sample. It’s not invasive,” said Mielke.

Despite the extensive research that Mielke and others have conducted on the widespread contamination of soil, due to both leaded gasoline emissions and paint, he points out that there are strict federal regulations in place for contaminated Superfund sites, but that’s not the case for residential soils.

“Residential properties where people are… aren’t getting any attention,” he said.

The soil around this swing set in an east Santa Ana yard tested above the residential lead soil level considered dangerous for children by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

A family’s uncertainty

In 2014, Maria Vasquez and her family moved about half a mile away from the Northwest Santa Ana home where her sons had tested positive for lead. The family moved because they needed more space. But her sister Leticia Vasquez and her family, who had moved into a one-room rental in the same home in 2012, remained there. They were unaware that the soil in the yard was contaminated with lead.

“When my sister said [Ulises] had high lead levels, we said ‘but from where? Where is it coming from?’ It was from here, because this is where he was born,” Leticia, sitting in the living room of that same home, said in Spanish. “We thought it was the paint, so we said let’s change the paint, let’s paint the house. But I never imagined that it could be the dirt.”

Since Ulises’ blood lead levels at the time didn’t meet the state level that would have triggered an environmental investigation, the Vasquez sisters’ concerns about the source of the lead were never addressed.

In the spring of 2016, ThinkProgress tested the soil in the home where Leticia, her husband and their two children, then ages 9 and 2 years, were living. The backyard soil tested well above the 80 parts per million level that the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) considers dangerous for children, with the highest soil test in the yard surpassing 800 ppm.

Leticia said she limited the childrens’ play area to the patio, away from the dirt in the front and back yard. She wanted keep her son, Ricardo, and daughter, Tania, from getting dirty. But keeping children from playing in a yard is no easy feat, she said.

“I try to make sure that they don’t play in the dirt, but I’ll no sooner say the words and they’re already in the dirt,” said Leticia. At the time, she said, her caution was based in her desire to keep her children clean, not because she was aware of the dangers of lead in the dirt.

High levels of soil lead in this northwest Santa Ana home exposed the children raised here to lead, including a newborn, a 2-year-old girl, and the 9-year-old boy seen here playing in his backyard. Lead exposure is the most dangerous for the developing brains of young children. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

After learning of ThinkProgress’ soil test results, Leticia called the office of her children’s pediatrician, and the clinic staff told her, based on Ricardo and Tania’s previous blood lead tests, that the children didn’t have any lead in their blood. And despite Leticia’s requests to see copies of the results to confirm the levels, the clinic did not provide her with the tests.

But Leticia was concerned: Ricardo had struggled to read and write starting in first grade. By the third grade, he was behind two grade levels in reading and math, struggled to finish his homework, and was almost held back twice over a period of two years. Leticia said she constantly received notes from Ricardo’s teacher because he couldn’t sit still, focus, or pay attention in class.

After the school assessed Ricardo at Leticia’s request and provided special education services to address his delays, Ricardo began to improve last year. He made progress in writing, Leticia said, but he continued to struggle with reading.

“He puts a lot of effort into his studies. He works really hard, but he can’t do the work,” said Leticia.

Last summer, Leticia gave birth to her third child. The family’s one-room rental became an even tighter squeeze. They had been searching for a more affordable rental, and earlier this year they were able to move to nearby Garden Grove.

Despite the assurances from her children’s clinic that her children were lead-free, the lead-contaminated soil in her yard still concerned Leticia.

“I didn’t know what lead was. They say candies and certain items contain lead,” said Leticia. “But I never imagined that the soil would have lead.”

A 2-year-old Santa Ana girl twirls in her front yard while playing with her dog and creates a cloud of dust. Soil that contains lead particles is dangerous for children who play in the dirt because it can become aerosolized and then inhaled. ThinkProgress found elevated levels of soil lead in the front and back yards of this home in northwest Santa Ana. CREDIT: Daniel A. Anderson for ThinkProgress

This project was made possible through the generous support of a community health reporting fellowship from the International Center for Journalists.

https://thinkprogress.org/urban-children-are-playing-in-toxic-dirt-41961957ff23

Interesting article and have my vote, your support is greatly appreciated by upvoting, resteeming, & following!

THANK YOU!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Omy goodness....!!!!!! This is SO SAD!!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

I know! Just terrible!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit