According to the official narrative, the COVID-19 pandemic began in Wuhan China around December 2019 with an outbreak of a mystery ‛pneumonia’, as Mandy Zuo called it in the South China Morning Post on 31 December:

State health authorities define “pneumonia of unknown cause” as cases where the patient suffers a fever higher than 38 degrees Celsius, has characteristics of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome present in imaging findings, has a normal or lowering white blood cell level or a falling absolute lymphocyte count, with no improvement after three to five days of antibacterial treatment. (Zuo)

In other words: Pneumonia of Unknown Etiology (PUE) is defined as a disease where the patient presents with typical symptoms of pneumonia but fails to respond to antibiotics. Such cases are assumed to be caused by pathogenic viruses, which are unaffected by antibiotics.

Usually, if a patient presents to their GP with symptoms typical of pneumonia, they may be diagnosed by their GP following a physical examination:

Diagnostic tests may be prescribed to confirm the diagnosis. What sort of tests? Let’s ask the American Lung Association:

The first test—Blood tests ... to try to identify the germ that is causing your illness—is the one we are interested in. As usual, the assumption is simply made that if you are ill, it must be due to a “germ”. The germ theory is now so deeply ingrained in modern medicine that this assumption is never questioned.

Question 1: Before COVID-19, was it standard procedure to carry out laboratory tests to identify the “germ” when a patient presented with symptoms typical of pneumonia?

Question 2: Can blood tests identify a virus that is allegedly causing pneumonia? The virus, assuming it exists, is infecting the lungs, not the blood.

My understanding is that a chest X-ray is generally considered sufficient to confirm a doctor’s diagnosis of pneumonia, while a CT (computed tomography) scan is considered definitive:

As has been discussed in this journal ... during the epidemic phase of COVID-19, numerous studies have given a key role to imaging techniques in the initial diagnostic management of the disease, be they chest X-ray as a first-line technique to confirm an initial diagnosis of pneumonia, or computed tomography (CT) as a second step, considered a “definitive” diagnostic test due to its high sensitivity and specificity. (Arenas-Jiménez et al 181)

In an earlier article in this series, I asked the question: What was so alarming about a handful of ordinary cases of pneumonia in a city of 12 million people that the Chinese medical authorities initiated a hunt for a novel virus? We now know that the images of people collapsing and dying in the streets of Wuhan were faked by the Chinese. Nothing remotely like that happened anywhere else in the world. The more I look into it, the more convinced I become that the whole pandemic was conjured up out of nothing.

But for the purposes of this study, let’s give the Chinese the benefit of the doubt. When they discovered that there was an outbreak of PUE in Wuhan, what did they actually do to discover the underlying cause?

Virus Hunters

In the summer of 2020, Mauritian Zaheer Allam, an urban strategist—whatever that is—from Deakin University in Melbourne, published one of the first studies of the pandemic, Surveying the Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Implications: Urban Health, Data Technology and Political Economy. Allam began his account with A Detailed Chronological Timeline and Extensive Review of Literature Documenting the Pandemic for the first 150 days of the pandemic (1 December 2019 – 28 April 2020). It is clear from his account of the first few days that the assumption has already been made, a priori, that there is a new virus circulating in the human population of Wuhan:

DAY 29—DECEMBER 29, 2019 ... With the possibility of an unknown outbreak, at this time, the concern was to establish the transmissibility, severity, and other issues that may be related to this new virus. (Allam 2)

At the end of December, the existence of a novel virus was still an assumption. It was not until one week later that the Chinese authorities first claimed to have discovered the virus responsible for the outbreak:

DAY 38—JANUARY 7, 2020 After rigorous probes, tests, analysis, and other medical practices, the Chinese authorities made a global announcement (Huang et al., 2020) that they have successfully identified the virus as a novel coronavirus, similar to the one associated with SARS and the middle east respiratory syndrome (MARS). Prior to this ground breaking discovery, the officials had 2 days earlier, on January 5, ruled out that the virus they were dealing with was either SARS or MARS, hence concluding that it was indeed a new type of virus. Upon its successful identification, it was tentatively named as “2019-nCoV.” The identification came after Chinese scientists successfully isolated the virus from one of the patients quarantined in a hospital in Wuhan (Huang et al., 2020). According to an article by Singhal (2020), the identified virus had greater than 95% (>95%) homology with the bat coronavirus and was also greater than 70% similarity with the virus responsible for causing SARS (SARS-CoV). (Allam 3)

The first source cited for this—Huang et al, 2020—is a paper published in English in The Lancet in February 2020:

- Chaolin Huang et al, Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, The Lancet, Volume 395, Issue 10223, Pages 497-506, Elsevier, London (2020)

The lead author, Chaolin Huang, is the deputy dean of Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, which was at the epicentre of the initial outbreak. On 22 January 2020, Huang was diagnosed with covid. Twenty-eight other authors are listed in the article’s byline. These include doctors and professors from more than a dozen other institutions in Wuhan and Beijing. Let’s take a closer look at this crucial paper.

Huang et al, 2020

The title of this paper, Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China (hereinafter referred to as Huang), already seems to be jumping the gun. Hopefully, the paper will prove to us that these patients were indeed infected with a novel coronavirus, and not simply assume this to have been the case.

The paper opens with a brief summary, giving the Background, Methods, Findings, Interpretation, Funding (and a Copyright notice in the PubMed Central’s online republication of the paper):

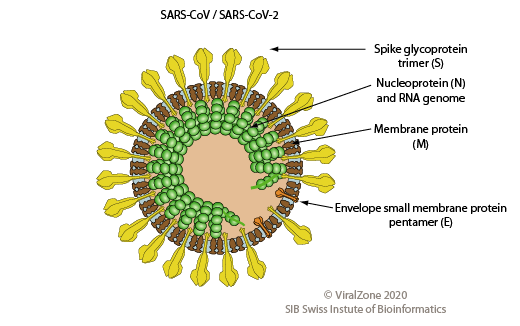

- a novel betacoronavirus, the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) (Huang 497)

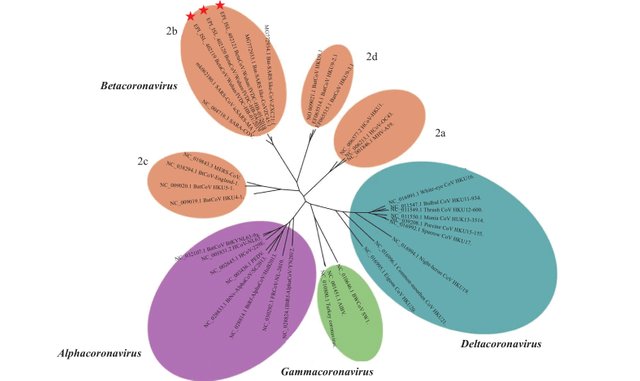

Betacoronavirus is a term used by virologists in the classification of viruses based on their genetic relationships. Although viruses are not alive, they are classified using a similar taxonomic system to the ones used to classify animals and plants, with the following taxonomic ranks:

- Realm

- Subrealm

- Kingdom

- Subkingdom

- Phylum

- Subphylum

- Class

- Subclass

- Order

- Suborder

- Family

- Subfamily

- Genus

- Subgenus

- Species

In this scheme, Betacoronavirus is a genus of the coronavirus family Coronaviridae. According to current thinking, this genus includes viruses that can cause the common cold in humans, as well as the viruses allegedly responsible for SARS, MERS and COVID-19.

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses changed the provisional name of this novel coronavirus from 2019-nCoV to SARS-CoV-2.

- We prospectively collected and analysed data on patients with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infection by real-time RT-PCR and next-generation sequencing. (Huang 497)

This is quite worrying. This is the paper which is alleged to have established that the outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology (PUE) in Wuhan at the end of 2019 was caused by a novel coronavirus. The discovery, isolation and genetic sequencing of a novel virus are necessary steps before an RT-PCR test can be developed to detect the presence of such a virus. As we learned in an earlier article in this series, PCR allegedly detects the presence of a virus by replicating a gene unique to that virus. Obviously, you cannot devise a PCR test for a given virus until that virus has been discovered, isolated and genetically sequenced. Following the completion of these steps, its genome is then compared with existing viral genomes to discover a gene or genetic sequence that is unique to it. Primers are then developed that match the ends of such a unique sequence.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is a technology that can determine the order of the nucleotides in entire genomes—allegedly. The basic process involves fragmenting the DNA or RNA into millions of pieces, adding adapters, sequencing the libraries, and reassembling them to form a genomic sequence. For the most part, this process is automated and is actually carried out by a computer, such as the Illumina HiSeq 2000 Sequencing System. Needless to say, we will have to investigate this process in a future article.

Introduction

In the following Introduction we read:

In December, 2019, a series of pneumonia cases of unknown cause emerged in Wuhan, Hubei, China, with clinical presentations greatly resembling viral pneumonia. Deep sequencing analysis from lower respiratory tract samples indicated a novel coronavirus, which was named 2019 novel coronavirus (2019- CoV). (Huang 497)

Now we are getting somewhere. This Deep Sequencing Analysis is what actually revealed the presence of a novel coronavirus. Deep Sequencing Analysis (DSA) is a method of sequencing a given genome several times in succession. Each time the genome is sequenced, random errors occur. By repeating the process—sometimes hundreds or even thousands of times—these errors, the argument runs, can be minimized. Deep Sequencing is, essentially, synonymous with Next Generation Sequence (Goldman & Domschke 1717). That is to say, it is the usual form taken by NGS. We will examine this process in a future article.

Huang and his co-authors go on to point out that no researchers before them claimed to have discovered or isolated any novel coronavirus in 2019:

We searched PubMed and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database for articles published up to Jan 11, 2020, using the keywords “novel coronavirus”, “2019 novel coronavirus”, or “2019-nCoV”. No published work about the human infection caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) could be identified. (Huang 498)

This merely confirms that this paper is indeed the one which describes the original discovery of this novel coronavirus.

Methods

The paper proceeds to describe the methods used in this study:

Following the pneumonia cases of unknown cause reported in Wuhan and considering the shared history of exposure to Huanan seafood market across the patients, an epidemiological alert was released by the local health authority on Dec 31, 2019, and the market was shut down on Jan 1, 2020. Meanwhile, 59 suspected cases with fever and dry cough were transferred to a designated hospital starting from Dec 31, 2019. An expert team of physicians, epidemiologists, virologists, and government officials was soon formed after the alert.

Since the cause was unknown at the onset of these emerging infections, the diagnosis of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan was based on clinical characteristics, chest imaging, and the ruling out of common bacterial and viral pathogens that cause pneumonia. Suspected patients were isolated using airborne precautions in the designated hospital, Jin Yin-tan Hospital (Wuhan, China), and fit-tested N95 masks and airborne precautions for aerosol-generating procedures were taken. (Huang 498)

This is quite vague. We are not told how they ruled out common bacterial and viral pathogens. Perhaps they ran RT-PCR tests calibrated to detect the presence of known bacterial and viral pathogens—with all the shortcomings of PCR as a diagnostic tool, which we have already studied in this series. Or were they able to rule out known pathogens through blood tests? Whatever the method used, why is it not mentioned? Reproducibility is one of the cornerstones of modern science, but other researchers cannot reproduce your results if you do not provide them with a detailed description of the methods you used.

Procedures

If the Methods section is sorely lacking in detail, the following Procedures section is criminally deficient:

Local centres for disease control and prevention collected respiratory, blood, and faeces specimens, then shipped them to designated authoritative laboratories to detect the pathogen (NHC Key Laboratory of Systems Biology of Pathogens and Christophe Mérieux Laboratory, Beijing, China). A novel coronavirus, which was named 2019-nCoV, was isolated then from lower respiratory tract specimen and a diagnostic test for this virus was developed soon after that. (Huang 498)

Our sole reason for studying this paper is to verify that a novel virus was indeed discovered, isolated and sequenced. But we are simply told that these steps were carried out. Not a single detail is given. Fortunately, this quotation has a citation:

14: Tan W, Zhao X, Ma X, et al. A novel coronavirus genome identified in a cluster of pneumonia cases — Wuhan, China 2019−2020. https://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/a3907201-f64f-4154-a19e-4253b453d10c (accessed Jan 23, 2020).

This refers to the following paper, which was published in China CDC Weekly, a weekly journal established by China’s Centre for Disease Control in November 2019, just as the pandemic was beginning (interesting timing):

- Wenjie Tan, Xiang Zhao, Xuejun Ma, et al, A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in a Cluster of Pneumonia Cases—Wuhan, China 2019-2020, China CDC Weekly, Volume 2, Issue 4, Pages 61-62, CCDC, Beijing (2020)

This, it seems, is the paper we ought to be studying. The remainder of Huang et al’s paper describes how the presence of their novel coronavirus was confirmed in various patients using this newly-developed PCR test, what treatments were given to these patients, and how they subsequently fared.

Wenjie Tan et al

This paper is only two pages long—short enough to quote in full (barring footnotes and captions). Could it provide the details missing from Huang?

Emerging and re-emerging pathogens are great challenges to the public health. A cluster of pneumonia cases with an unknown cause occurred in Wuhan starting on December 21, 2019. As of January 20, 2020, a total of 201 cases of pneumonia in China have been confirmed. A team of professionals from the National Health Commission and China CDC conducted epidemiological and etiological investigations. On January 3, 2020, the first complete genome of the novel β genus coronaviruses (2019-nCoVs) was identified in samples of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from a patient from Wuhan by scientists of the National Institute of Viral Disease Control and Prevention (IVDC) through a combination of Sanger sequencing, Illumina sequencing, and nanopore sequencing. Three distinct strains have been identified, the virus has been designated as 2019-nCoV, and the disease has been subsequently named novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia (NCIP). (Tan et al 61)

Note that there is no mention here of the discovery or isolation of any virus. Only genetic sequencing was carried out using three techniques: Sanger Sequencing, Illumina Sequencing, and Nanopore Sequencing.

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between 2019-nCoVs and other sequences under the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily using MAFFT v7.455 (Figure 1), and maximum likelihood inference was calculated using PhyML v3.3, employing the GTR + I + Γ model of nucleotide substitution, and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The 2019-nCoVs have features typical of the coronavirus family and were placed in the Betacoronavirus 2b lineage. Alignment of these strains’ full genomes and other available genomes of Betacoronavirus showed the closest relationship with Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZC45 (Accession Number: MG772933.1) (Identity 87.99%). The typical crown-like particles of the 2019-nCoVs can be observed under transmission electron microscope (TEM) with negative staining (www.gisaid.org). The origin of the 2019-nCoVs is still being investigated. However, all current evidence points to wild animals sold illegally in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. (Tan et al 61-62)

Those who believe in the existence of SARS-CoV-2 are still investigating its origins. The initial theory that it was first transmitted to humans from a bat at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was undermined when it transpired that bats were not sold at that market. Another theory suggested that pangolins acted as an intermediate host between bats and humans. Although there is an illicit market for pangolins in China, this theory has lost ground.

Several complete genome sequences of 2019-nCoVs were successfully obtained and released recently via www.gisaid.org to provide a first look at the molecular characteristics of this emerging pathogen, and all related information has also been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO). Several rapid and sensitive detection tests have been developed by China CDC and will be applied to the prevention and control of this 2019-nCoV outbreak. (Tan et al 62)

GISAID is the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data, a non-profit organization that was originally set up in 2008—just months before the Swine Flu Pandemic of 2009 (interesting timing)—to provide open access to genomic data of influenza viruses.

Data availability. The new Betacoronavirus genome sequence has been deposited in GISAID (www.gisaid.org) under the accession number EPI_ISL_402119, EPI_ISL_ 402020 and EPI_ISL_402121. (Tan et al 62)

And that’s it. The authors of this paper, like Huang et al, do not describe how the novel coronavirus was discovered or isolated. In fact, they do not even claim to have discovered or isolated any novel virus. The only claim they make is to have identified and sequenced a novel genome.

Did the Chinese scientists ever isolate a novel coronavirus?

Wu Zunyou

In an interview with NBC Nightly News, Dr Wu Zunyou, the Chief Epidemiologist at the China Centre for Disease Control, admitted in no uncertain terms that the novel coronavirus was never actually isolated by the Chinese researchers. The interview was broadcast on 23 January 2021, approximately one year after the publication of the two papers we have been studying in this article:

The full program can be watched here (Relevant Timestamp = 11:25):

How can anyone call the claim that the virus was never isolated a conspiracy theory when the Chief Epidemiologist at China’s CDC has plainly admitted it? Nevertheless, this lie is still being propagated by the World Health Organization and its shills. One such shill is Elizabeth Marnik, who describes herself as scientist, professor and a passionate science communicator:

Has the virus that causes COVID-19 never been isolated?

Mar 27 Another common myth is that the cause of COVID-19 has never been isolated so a vaccine can’t exist. This is a lie. A sample from a sick patient in China at the start of the pandemic was collected and the virus was identified on January 7th, 2020.

Below is from the WHO:

“The cluster was initially reported on 31 December 2019, when the WHO China Country Office was informed. The Chinese authorities identified a new type of coronavirus (novel coronavirus, nCoV), which was isolated on 7 January 2020. Laboratory testing was conducted on all suspected cases identified through active case finding and retrospective review. Other respiratory pathogens such as influenza, avian influenza, adenovirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) were ruled out as the cause.”

You can even find the whole genome sequence for SARS-CoV-2 (virus that causes COVID-19) online. You can also find many papers about its genome and other work with the virus. This all requires that we have isolated samples. (1,2). These papers could not have been published otherwise.

Bottom Line:

There is zero truth to this myth circulating.

It is very easy to isolate a virus from a patient sample and then use that sample for research. Isolated SARS-CoV-2 virus was also used to sequence its genome (the RNA directions that code for the virus).

Once scientists had the genome they used that information to make the vaccines.

The isolated virus is also being studied in labs all over the world to try to develop treatments and learn more to stop the pandemic. When you hear about experiments done “in a dish” many of those use isolated virus.

So anytime you hear this myth, know that it is not true and be skeptical of any other information in the same post. (Marnik)

The Chinese announcement on 7 January did not claim that a novel coronavirus was isolated on 7 January 2020, as the WHO states. The date the Chinese gave was 3 January, and this is what they actually announced:

On January 3, 2020, the sequence of novel β-genus coronaviruses (2019-nCoV) was determined from specimens collected from patients in Wuhan by scientists of the National Institute of Viral Disease Control and Prevention (IVDC), and three distinct strains have been established (2). On January 7, this novel coronavirus was confirmed to be the pathogenic cause of this VPUE cluster, and the disease has been designated NCIP. (CCDC Weekly)

We have already seen how no virus was discovered or isolated: they only carried out genome sequencing.

Note how Marnik commits the logical fallacy known as Circular Reasoning, in which the desired conclusion is assumed as the premise of the argument leading to that conclusion:

You can even find the whole genome sequence for SARS-CoV-2 (virus that causes COVID-19) online. You can also find many papers about its genome and other work with the virus. This all requires that we have isolated samples. (Marnik)

I am willing to concede that one must first isolate the virus before one can sequence its genome. But presenting a genome and claiming that it is the genome of SARS-CoV-2 cannot possibly be cited as evidence that SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated. The very thing we wish to establish—that SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated—is necessary before we can say that this sequence is the genome of SARS-CoV-2. It is quite shocking to find a PhD committing such a fallacy.

A quick search online for other claims to have isolated SARS-CoV-2 or one of its variants reveals that the same procedure is being used elsewhere. For example, in Australia virologists developed what they call R-20, a Platform for isolation and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 variants:

Genetically distinct variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have emerged since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Over this period, we developed a rapid platform (R-20) for viral isolation and characterization using primary remnant diagnostic swabs. This, combined with quarantine testing and genomics surveillance, enabled the rapid isolation and characterization of all major SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating in Australia in 2021. Our platform facilitated viral variant isolation, rapid resolution of variant fitness using nasopharyngeal swabs and ranking of evasion of neutralizing antibodies. (Aggarwal et al 896)

And how are these variants isolated?

... the majority of variants under investigation (VUI) were detected through rapid whole-genome sequencing (WGS) ... Whole-genome viral sequencing. Clinical respiratory specimens positive by diagnostic SARS-CoV-2 PCR were sequenced using a combination of Nanopore single-molecule sequencing and amplicon-based Illumina sequencing approach, as previously described 11 . Consensus SARS-CoV-2 genomes have been uploaded to GISAID (www.gisaid.org) and are publicly available ... (Aggarwal et al 896 ... 906)

To be fair, the authors of this paper do describe in minute detail how they initially detected and isolated the virus before developing the R-20 platform. They did this by culturing the assumed virus, observing so-called cytopathic effects (CPE), and only then carrying out genome sequencing. Unlike the Chinese virologists, the authors of this paper provide a wealth of details describing their precise methods and the procedures they followed at every step of the process. This is how it should be done, and the authors are to be commended for their openness, which is in stark contrast to the laconic hand-waving of the Chinese virologists.

In the next article, we will take a close look at this culturing process with its cytopathic effect, which has become the accepted method of isolating viruses in mainstream medicine.

Conclusions

None of the papers commonly cited as proof that SARS-CoV-2 was discovered and isolated in accordance with the principles of modern science actually describes in a reproducible manner how the authors first discovered and isolated a novel coronavirus. We are simply told which standard processes were used to sequence the genome of the assumed virus. One year later, the Chief Epidemiologist at China’s CDC admitted that the virus was never isolated.

And that’s a good place to stop.

References

- Anupriya Aggarwal et al, Platform for Isolation and Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Variants Enables Rapid Characterization of Omicron in Australia, Nature Microbiology, Volume 7, Issue 6, Pages 896-908, Nature Portfolio, London (2022)

- Zaheer Allam, Surveying the Covid-19 Pandemic and Its Implications: Urban Health, Data Technology and Political Economy, Elsevier, Amsterdam (2020)

- J J Arenas-Jiménez, J M Plasencia-Martínez, E. García-Garrigós, When Pneumonia is not COVID-19, Radiología, Volume 63, Issue 2, Pages 180-192, Spanish Society of Medical Imaging (SERAM), Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection (2021)

- D Goldman & K Domschke, Making Sense of Deep Sequencing, International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, Volume 17, Issue 10, Pages 1717–1725, Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

- Chaolin Huang et al, Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China, The Lancet, Volume 395, Issue 10223, Pages 497-506, Elsevier, London (2020)

- Wenjie Tan, Xiang Zhao, Xuejun Ma, et al, Notes from the Field: A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in a Cluster of Pneumonia Cases—Wuhan, China 2019−2020, China CDC Weekly, Volume 1, Number 4, Beijing (2020)

- Wenjie Tan, Xiang Zhao, Xuejun Ma, et al, A Novel Coronavirus Genome Identified in a Cluster of Pneumonia Cases—Wuhan, China 2019-2020, China CDC Weekly, Volume 2, Issue 4, Pages 61-62, CCDC, Beijing (2020)

- The 2019-nCoV Outbreak Joint Field Epidemiology Investigation Team, Qun Li, An Outbreak of NCIP (2019-nCoV) Infection in China—Wuhan, Hubei Province, 2019−2020, China CDC Weekly, Volume 2, Issue 5, Pages 79-80, Beijing (2020)

- WHO, WHO-Convened Global Study of the Origins of SARS-CoV-2, World Health Organization, Geneva (2021)

- Yu-Chi Wu, Ching-Sung Chen, Yu-Jiun Chan, The Outbreak of COVID-19: An Overview, Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, Volume 83, Issue 3, Pages 217-220, Taipei (2020)

- Na Zhu et al, _A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019 _, The New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 382, Number 8, Pages 727-733, Massachusetts Medical Society, Waltham, MA (2020)

Image Credits

- COVID-19 Poster: © 2021 Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Fair Use

- Staged Covid Victim in Wuhan, China: © Héctor Retamal (photographer), Agence France-Presse, Fair Use

- Zaheer Allam: © Zaheer Allam, Fair Use

- Chaolin Huang and Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital: © China Central Television (CCTV), Fair Use

- Supposed Structure of SARS-CoV-2: © ViralZone (designers), Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB), Fair Use

- Illumina’s NextSeq 550Dx: © Illumina, Inc, Fair Use

- Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital: © Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, Fair Use

- The Reproducibility Crisis: © Brett Underhill (animator), TED-ed, Fair Use

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing: © China CDC, Fair Use

- Phylogenetic Relationships of Orthocoronavirinae Genomes: © Wenjie Tan et al (designers), Fair Use

- Elizabeth Marnik: © Elizabeth Marnik (photographer), Fair Use

- Circular Reasoning: WearYourDictionary (designer), Deviant Art, Creative Commons License

- Anupriya Aggarwal of the Kirkby Institute: © Anupriya Aggarwal (photographer), Fair Use

Video Credits

- Wu Zunyou: Maximilian Davis, Fair Use

- NBC Nightly News 23 January 2021: NBC Nightly News, © NBC Universal, Fair Use

Online Resources

- RIP.ie

- Central Statistics Office (CSO)

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA)

- EUROMOMO

- Our World in Data

- Rational Ground