“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Richard Feynman (from the lecture ‘What is and What Should be the Role of Scientific Culture in Modern Society’, in Italy 1964).

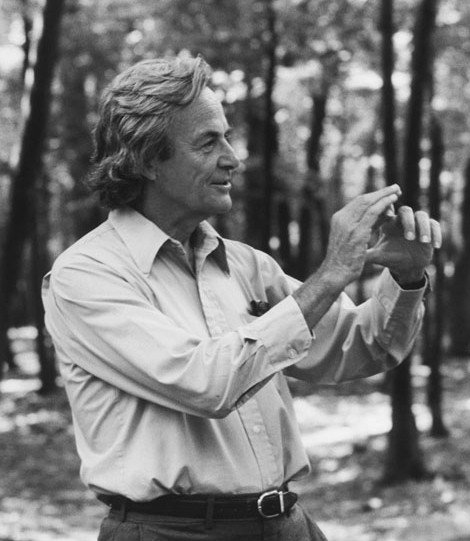

Richard Feynman in the woods of the Robert Treat Paine Estate in Waltham, MA (1984). Photographer: Tamiko Thiel.

How do we determine what is true? The absolute and incontrovertible truth. The kind of “…truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth…” that the judiciary expects from a witness. The kind of truth that Jack Nicholson fears we are not equipped to handle (A Few Good Men, 1992).

René Descartes, a 16th century French philosopher and widely regarded as the father of modern western philosophy, was interested in this very question. He was also an astute mathematician and a scientist. If you have ever plotted a X-Y graph to determine the relationship between the number of exes you called (x-axis) and the number of vodka shots you downed (y-axis) on any Friday night-out, you were using the Cartesian coordinate system!

Renaissance was winding down at the time in Europe, gradually paving the way for the Scientific Revolution. Nicolaus Copernicus hustled it in 1543, with the publication of his book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which placed the Sun rather than the Earth at the centre of the Universe. This went against five millennia of Ptolemic geocentric dogma and directly contradicted the King James Bible, Psalm 104:5, “[the Lord] Who laid the foundations of the earth, that it should not be removed for ever.” Do share in the comments section how terrifying it is for you to contradict your boss in the weekly team meetings!

The air was with ripe with anarchy. Everything was up for grabs. Radical skepticism, the school of thought that posited, ‘knowledge is most likely impossible’ was gaining traction and impeding progress. It was then that Descartes came to the rescue with arguably the most famous quote in human history, the cogito,

“je pense, donc je suis” (French), Discourse on the Method (1637).

“Cogito ergo sum” (Latin), Principles of Philosophy (1644).

Usually translated to English as “I think, therefore I am”, the cogito went on to become a cornerstone of Western philosophy and provide much needed respite from radical skeptics. It also helped form a secure methodology of seeking knowledge during uncertain and turbulent times, the Cartesian doubt.

The beauty of the cogito lies in its elegant simplicity. Here Descartes proposes that we can doubt everything to be untrue but we can not doubt our own existence. Because our ability to doubt is predicated on the reality of our existence. There must be a thinking entity for there to be a thought.

So there is a bedrock truth that everyone can unanimously agree on to be true, and it is that ‘we exist’. And we can find our way to other truths from there.

In 1765, Antoine Thomas expanded this truism for the benefit of those who do not wish to read groundbreaking 16th century French and Latin texts,

“Puisque je doute, je pense; puisque je pense, j’existe” (French).

“dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum” (Latin).

I doubt, therefore I think, therefore I am.”

I won’t argue with you if you think all this philosophizing is a bit too much. After all, outside of fans of Russian bath salts, questioning one’s existence is a bit esoteric, to say the least. However the cogito’s true achievement is the birth of a systematic methodology of seeking the truth, formally known as Cartesian doubt.

Cartesian doubt is used to arrive at basic or foundational beliefs that can not be doubted. They are self-evident. Such beliefs have entered the popular lexicon as First principles, and is especially taking Silicon valley by storm (and with astounding results to boot). Here is what the greatest entrepreneur of our time has to say about the power of First principles,

“I think it is important to reason from first principles rather than by analogy. The normal way we conduct our lives is we reason by analogy. [When reasoning by analogy] we are doing this because it’s like something else that was done or it is like what other people are doing — slight iterations on a theme.

First principles is kind of a physics way of looking at the world. You boil things down to the most fundamental truths and say,

“What are we sure is true?” … and then reason up from there.”

Elon Musk (in an interview with Kevin Rose, 2012)

Cartesian doubt is a methodology whose purpose is to use doubt as a tool to parse truths from falsehoods, to find knowledge that can no longer be doubted (like your own existence). And once you have found such indubitable knowledge (also known as basic or foundational beliefs), you build upon them to derive further knowledge. A famous example of Cartesian doubt in action follows,

“Somebody could say, “Battery packs are really expensive and that’s just the way they will always be… Historically, it has cost $600 per kilowatt hour. It’s not going to be much better than that in the future.”

With first principles, you say, “What are the material constituents of the batteries? What is the stock market value of the material constituents?”

It’s got cobalt, nickel, aluminum, carbon, some polymers for separation and a seal can. Break that down on a material basis and say, “If we bought that on the London Metal Exchange what would each of those things cost?”

It’s like $80 per kilowatt hour. So clearly you just need to think of clever ways to take those materials and combine them into the shape of a battery cell and you can have batteries that are much, much cheaper than anyone realizes.”

Elon Musk (same interview with Kevin Rose, 2012)

Do you see now? For each of your problems, there are two ways of going about solving them.

The easiest and likely the fastest way is by proxy or analogy. Entity X had a similar problem and they solved it by solution Y. So solution Y (or a slight variation of it) is the answer to my problem. It may very well be. After all, human progress depends on not having to reinvent the wheel every few days.

However one can reasonably argue that radical solutions to intractable problems can only happen by doubting everything until you don’t have to, thereby arriving at first principles that will afford you with an unique perspective on your problem. All the disruption that you hear is happening in Silicon valley every day, is a testament to the power of Cartesian doubt in action.

Besides aiding decisions in problem-solving, Cartesian doubt is also an incredibly powerful learning tool. Because at the end of the process, what one arrives at is intuition. And there is no arguing with what is intuitively and self-evidently true. Learning by intuition is fun because it is not ‘learning’ if you don’t have to ‘remember’ it. Just like you don’t have to remember you exist, you just do.

However to apply Cartesian doubt to learning, one must, by definition, question authority. Descartes refused to accept the authority of previous philosophers and proclaimed that he will write on this topic (emotions in this case),

“as if no one had written on these matters before” (Passions of the Soul, 1649).

Therefore, I am planning to create a series of intuitive publications on Medium that leverages the power of Cartesian doubt to understand and appreciate complex subjects that have resisted mainstream acceptance, in spite of being nothing short of revolutionary.

The first publication is about the neuroscience of decision-making and how we can leverage what we understand about our brains to make good decisions. I don’t need to remind you how bad it is right now for everyone involved. We are endangering our health, our education and most importantly, the future of the planet and everything on it, with decisions that are unfathomably idiotic and rash.

I sincerely believe knowledge is the antidote here. Our brains, although marvelous organs, are far from perfect. It is riddled with biases and is remarkably bad at making good decisions that remain so in hindsight. However it is also an extraordinarily pliable machine and armed with the knowledge of what ails it, can steer itself into doing the right thing.

The second publication is about the fourth industrial revolution that we are in but that has somehow managed to elude mainstream public awareness so far. The blockchain revolution is here and it is going to fundamentally alter our way of life in the not so distant future. This publication seeks to make blockchain technology and its underlying crypto-economic principles accessible to the colloquial average Joe.

I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I do writing them.

I leave you with the these words from my fountain of eternal inspiration. Stay curious!

“Do your own homework. To truly use first principles, don’t rely on experts or previous work. Approach new problems with the mindset of a novice. Truly understand the fundamental data, assumptions and reasoning yourself. Be curious.”

Richard P. Feynman (All the Adventures of a Curious Character, 2005).

Today is the birth of Intuitive Publications. All rights reserved.

Good article

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @calvinginger! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard!

Participate in the SteemitBoard World Cup Contest!

Collect World Cup badges and win free SBD

Support the Gold Sponsors of the contest: @good-karma and @lukestokes

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @calvinginger! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit