Lately I came by with a very fascinating post, that I read it with full attention. As a lot of other users here on steemit, I too have started with cryptoworld a few years back. And I think that cryptoworld is full of great inventions and opportunities, as is also a great for hidden traps and heavy losses. Going in without a clear head and not being cautious with tradings, can make people lose everything.

This is why today I post, one of the best post I have read on how to invest smart and came out with more than you have invest.

Ever since Nas Daily’s video came out about how I earned over $400,000 with less than $10,000 investing in Bitcoin and Ethereum, I’ve been getting hundreds of questions from people around the world about how to get started with cryptocurrency investment.

First: I’m super glad there’s so much interest in cryptocurrency right now. I firmly do believe that cryptocurrency and blockchain technology has the potential to fundamentally change much of the way our world currently operates for the better. It reminds me a lot of the internet in the 90s.

Second: Investment in cryptocurrency isn’t something to be taken lightly. It’s extremely risky, extremely speculative, and extremely early stage still at this point in time. Countless speculators and day traders have lost their entire fortunes trading cryptocurrency. I was no different when I first started investing in crypto. The first $5000 I put into crypto fell almost immediately to less than $500 — a net loss of over 90%.

Third: All of the following words are entirely and solely my own opinion, and do not reflect any objective truth in the world or the opinions or perspective of any other individual or entity. I write them here merely so people can know how I personally approach cryptocurrency, and what I have personally found helpful in my foray into this realm.

I’m firmly of the opinion that one should never invest in something one doesn’t thoroughly understand, so I’m going to split this article into three parts.

The first part will speak to a broad explanation of what bitcoin and cryptocurrency at large are. The second will discuss my personal investment philosophy as it pertains to crypto. The third will show you step by step how to actually begin investing in crypto, if you so choose. Each section will be clearly delineated, so feel free to skip parts if they’re already familiar to you.

Part I: What is Bitcoin? Why is it useful?

Great question. If you want the full story behind the advent of bitcoin, I highly recommend the book Digital Gold. It traces the entire history of bitcoin from its inception all the way up to 2015. It’s an engrossing read, and highly informative.

For now, let’s start with a quick history lesson about bitcoin. Bitcoin was officially unveiled to the public in a white paper published October 31st, 2008. The white paper is actually extremely readable, very short (just 8 pages), and incredibly elegantly written. If you want to understand why bitcoin is so compelling straight from the horse’s mouth, you must read this paper. It will explain everything better than I or anyone else likely ever could.

I won’t delve too much into the technical details of how bitcoin works (which are better elucidated in the white paper), but will instead focus on a broader exploration of its history and implications.

Subpart: The Background Context of Bitcoin

Bitcoin was invented in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and the crisis was a clear motivating factor for its creation.

Numerous banks and other financial institutions failed across the world, and had to be bailed out by governments at the expense of their taxpayers. This underscored the fragility of the modern financial system, where the health of our monetary system is reliant on banks and other financial institutions that we are forced to trust to make wise and prudent decisions with the money we give them. Too often for comfort, they fail to carry out this fiduciary responsibility to an adequate degree. Of particular note is fractional reserve banking. When you give a bank $1,000, the bank doesn’t actually keep all that money for you. It goes out and is legally allowed to spend up to $900 of your money, and keep just $100 in the off chance that you ask for your money back.

In the most simplistic case, if you are the only depositor at this bank, and you ask for more than $100 back at once, the bank won’t be able to give you your money, because it doesn’t have it any more.

Shockingly, this is actually how banks work in reality. In the United States, the reserve requirement, or the percentage of net deposits banks are actually required to keep in liquid financial instruments on hand, is generally 10% for most banks. This means that if a bank has net deposits of a billion dollars, it needs to only keep 100 million on hand at any given time.

This is fine most of the time, as generally the customers of that bank won’t all try to cash out at the same time, and the bank is able to stay liquid. However, the moment customers start to question the bank‘s financial stability, things can go south very quickly. If just a small number of customers begin asking for all their deposits back, a bank can rapidly become depleted of all its liquid funds.

This leads to what’s known as a bank run, where the bank fails because it is unable to fulfill all the withdrawals customers demand. This can escalate quickly into a systemic bank panic, where multiple banks begin to suffer the same fate. Each successive failure compounds the collective panic, and quite quickly, the whole system can begin to collapse like a house of cards.

This is what led in large part to the Great Depression, for instance. The whole system is fundamentally predicated on trust in the system, and the second that vanishes, everything can go south incredibly quickly.

The financial crisis of 2008 highlighted yet another risk of the modern banking system. When a bank goes out and spends the 90% of net deposits it holds in investments, it can often make very bad bets, and lose all that money. In the case of the 2008 crisis, banks in particular bet on high risk subprime mortgages. These were mortgages taken out by borrowers very likely to become delinquent, to purchase houses that were sharply inflated in value by the rampant ease of acquiring a mortgage.

When those mortgages were defaulted on, the artificially inflated values of the homes began to collapse, and banks were left holding assets worth far less than the amount they had lent out. As a consequence, they now had nowhere near the amount of money that customers had given them, and began experiencing liquidity crises that led to their ultimate bankruptcy and demise.

After the Great Depression occurred, the government attempted to address this issue by creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which technically guarantees all customer deposits in participating banks up to $250,000 per account.

Unfortunately, the FDIC is just as dramatically underfunded as banks are. As the FDIC itself acknowledges, it holds enough money to cover just over 1% of all the deposits it insures. In other words, if banks reneged on any more than 1% of all their deposits, the FDIC itself would also fail, and everyone would yet again be left in the dust without recourse.

In fact, this has already happened. The FDIC used to have a sister corporation that insured savings and loan institutions, as it itself at the time only insured bank deposits, and not savings and loan institution deposits. This was known as the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation, or FSLIC.

In the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, over 1,000 of the 3,200 savings and loan institutions in the United States failed in rapid succession. The FSLIC almost immediately became insolvent itself, and had to be recapitalized several times with over $25 billion dollars of taxpayer money. Even this didn’t even come close to being sufficient to solve the crisis, and the FSLIC managed to only resolve the failure of less than 300 of the 1000 bankrupt institutions, even with all the handouts from taxpayers, before it just flat out gave up and dissolved itself.

For the most part, things generally work fine on a day to day basis. This belies, however, the true fragility of the system. It’s hard to anticipate these things before they happen, because it’s so easy to fall into the trap of assuming that things will always be as they mostly always have been. If things have been fine yesterday, and the day before, and the few years before that, or even the few decades before that, we just naturally assume that they will continue to be fine for the indefinite future.

History has proven this to be an often fatal assumptive error. The second things start to stop working, they tend to stop working in an extremely rapid, catastrophic fashion. There’s very little, if anything, stopping us from seeing another Great Depression sometime in the future, be it the near or longer term future. When that does happen — and it almost certainly will, sooner or later, if history is any good teacher — those who haven’t adequately prepared for it and taken appropriate prophylactic measures may very well find themselves in a bad spot.

Subpart: Fiat Currencies Compound the Dilemma

Mistrust in fiat currencies, or currencies created and backed solely by faith in a government, both because of the modern banking system and because of the inherent nature of fiat currency, has in large part been why gold has been used as such a reliable store of value over millennia.

Fiat currencies are the world’s predominant form of currency today. The US dollar or the British pound, for instance, are fiat currencies. These are currencies that are entirely controlled in their supply and creation by a national government, and are backed by nothing but faith in that government.

This has proved a mistake countless times throughout history. Zimbabwe is a classic example, where the Zimbabwean dollar, thanks to an incompetent government among other factors, experienced enormous levels of hyperinflation. At one point, inflation was estimated at almost 80 billion percent in just a single month.The following image gives an idea of just how rapidly and absurdly a fiat currency can spiral out of control, once it reaches the point of no return.

Lest we think this an isolated instance, Venezuela is experiencing incredibly similar hyperinflation in the present-day, right this moment. The Venezuelan Bolívar inflated over 800% in 2016, and shows no signs of stopping in 2017.

The US hasn’t been immune to these crises, either. The US began its foray into fiat currency with the issuance of Continental Currency in 1775. Just three years later, Continental Currency was worth less than 20% of its original value. 13 years later, hyperinflation entirely collapsed the currency, and the US had to pass a law guaranteeing that all future currencies would be backed by gold and silver, and that no unbacked currencies could be issued by any state.

In comparison, the early history of the US dollar makes the relative volatility of bitcoin in these first 9 years look like peanuts.

Once adopted out of necessity, the gold standard became part and parcel of US currency, just as it was with most other currencies from around the world. The gold standard removed some of the need to have pure faith in US dollars in of themselves, as it guaranteed that all paper money the US issued would be exchangeable at a fixed rate for gold upon demand.

Naturally, you still had to believe that the government would actually keep enough gold to fulfill all these demands (déjà vu and foreshadowing, anyone? Any flashbacks to fractional reserve banking yet?), but it was certainly better than nothing. Gold, unlike fiat currencies, requires no trust and faith in a government to responsibly manage its money supply and other financial dealings in order to believe that it will retain its value well over time. This is because gold has no central authority that controls it and effectively dictates its supply and creation arbitrarily. Gold is fundamentally scarce, and only a small amount of it can be mined every year and added to the whole net supply. To date, the estimated total of all the gold ever mined in the history of humankind is only 165,000 metric tons. To put that in perspective, all that gold wouldn’t even fill up 3.5 Olympic sized swimming pools. No government, no matter how much they wanted to or needed to, could simply conjure up more gold on demand. Fiat currencies, on the other hand, can and often have been printed on demand by governments whenever they happened to be short on cash and needed a quick infusion.

This printing of more money generally leads to inflation, as the total value of all the money in existence rationally should stay the same, no matter how many dollars are printed. Hence, if more dollars are printed, each dollar is worth fractionally less of the total money supply.

In fact, governments design their currencies and monetary policies to inflate intentionally. This is why $100 US dollars in 1913 (when the government officially started tracking inflation rates) is equivalent to $2,470 dollars today, just over 100 years later.

In fact, the average inflation rate of the US dollar over that time period was about 3.22%. This seems low, but in reality means that prices double just every twenty years. In other words, your money becomes half as valuable if you keep it in US dollars every twenty years. Doesn’t seem ultra cool to me.

Gold, on the other hand, doesn’t inflate like fiat currencies do. That’s because there’s an intrinsically limited supply, and consequently, things tend to cost the same in gold over long periods of time. In fact, 2,000 years ago, Roman centurions were paid about 38.58 ounces of gold. In US dollars today, this comes out to about $48,350. The base salary of a captain in the US army today comes out to just about the same at $48,500.

This makes gold, in many ways, a better store of value based on fundamental principles than fiat currencies over time. You don’t have to trust anyone to trust that your gold will retain its value relatively well across the sands of time.

Unfortunately, the gold standard collapsed multiple times during the 20th century and was ultimately abandoned altogether by almost every nation in the world, because governments effectively played fractional reserve banking with their gold reserves.

Who could blame them? It must be irresistibly tempting, knowing that in all likelihood, the vast majority of the time, only a fraction of people will ever want to trade in their dollars for gold. Why hold all that gold when you could hold just a fraction of it and get to spend the rest with no consequences in the short term?

Inevitably, this caught up with each and every government over time. For the United States, the gold standard was suspended in the aftermath of the Great Depression. The Bretton Woods international agreement instituted in the aftermath of World War II restored the gold standard to the US dollar, but this was short lived.

Under the Bretton Woods system, numerous foreign governments held US dollars as an indirect and more convenient method of holding gold, as US dollars were supposedly directly exchangeable at a fixed rate for gold. However, by 1966, gold reserves actually held by the US were already pitifully low, with only $13.2 billion worth of gold being held by the government.

By 1971, other governments had caught on to this, and began demanding the exchange of all their US dollars for gold, as was promised to them. Naturally, the US had nowhere near enough gold to fulfill their promises, and this became a government version of the bank run, essentially.

The US chose instead to fully renege on their promised exchange rate, and announced in what was known as the Nixon shock that the US dollar would no longer be redeemable for gold, and would henceforth be backed solely by faith in the US government (very faith-inspiring, no?).

Almost every nation quickly followed suit, and since then, fiat currencies have been allowed free reign to grow as they please with no accountability whatsoever in how much a government chooses to expand their money supply.

This, thus, requires anyone holding fiat currencies to have extreme trust that their government will manage their money supply responsibly, and not make poor financial decisions that will severely devalue the currency they hold. This compounds with the trust one must hold in the banks in which one deposits their fiat currency, to create an ultimate monetary system that has multiple points of very real possible failure, as history has shown time and again.

Holding gold privately removes the need to trust either of these points of failure in the modern banking system, but comes with its own host of problems. Namely, while gold has proven to be an excellent store of value over time, it is incredibly poor for actual day to day use in the modern economy. To transact with gold is excessively cumbersome and inconvenient. No one would consider walking around with an ounce of gold on them, measuring and shaving off exact portions of gold to pay for a cup of coffee, groceries, or a bus ride. Worse, it’s even more difficult and time consuming to send gold to anyone who isn’t physically in the same exact location as you.

For these reasons among others, fiat currencies have traditionally been preferred for everyday use, despite their many shortcomings and associated inherent risks.

No solution to this tradeoff conundrum has heretofore been discovered, or even necessarily possible. Bitcoin, however, with the aid of recent technological advances (computers and the internet), solves all of these issues. It takes the best of both worlds, and puts it into one beautiful, elegant solution.

Subpart: Bitcoin to the Rescue

Holy long-windedness, batman! 2,700 words later, and we finally get to talking about bitcoin. I’m as relieved as you are. Remind me never to write again.

Bitcoin was designed, essentially, as a better ‘digital gold’. It incorporates all of the best elements of gold — its inherent scarcity and decentralized nature — and then solves all the shortcomings of gold, in allowing it to be globally transactable in precise denominations extremely quickly.

How does it do this? In short, by emulating gold’s production digitally. Gold is physically mined out of the ground. Bitcoin is also ‘mined’, but digitally. The production of bitcoin is controlled by code that dictates you must find a specific answer to a given problem in order to unlock new bitcoins.

In technical terms, bitcoin utilizes the same proof-of-work system that Hashcash devised in 1997. This system dictates that one must find an input that when hashed, creates an output with a specific number of preceding zeros, among a few other specific requirements.

This is where the ‘crypto’, incidentally, in cryptocurrency comes from. Cryptographic hash functions are fundamentally necessary for the functioning of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, as they are one-way functions. One-way functions work such that it is easy to calculate an output given an input, but near impossible to calculate the original input given the output. Hence, cryptographic one-way hash functions enable bitcoin’s proof of work system, as it ensures that it is nigh-impossible for someone to just see the output required to unlock new bitcoins, and calculate in reverse the input that created that output.

Instead, one must essentially brute-force the solution, by trying every single possible input in order to find one that creates an output that satisfies the specified requirements.

Bitcoin is further ingeniously devised to guarantee that on average, new bitcoins are only found every 10 minutes or so. It guarantees this by ensuring that the code that dictates the new creation of bitcoin automatically increases the difficulty of the proof-of-work system in proportion to the number of computers trying to solve the problem at hand.

For instance, in the very beginning of time, it was only the creator of bitcoin who was mining for bitcoins. He used one computer to do so. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume this one computer could try 1000 different values to hash a second. In a minute, it would hash 60,000 values, and in 10 minutes, 600,000 values.

The algorithm that dictates the mining of bitcoins, therefore, would ensure that on average, it would take 600,000 random tries of hashing values to find one that would fulfill the requirements of the specified output required to unlock the next block of bitcoins.

It can do this by making the problem more or less difficult, by requiring more or less zeros at the beginning of the output that solves the problem. The more zeros that are required at the beginning of the output, the more exponentially difficult the problem becomes to solve. To understand why this is, click here for a reasonably good explanation.

In this case, it would require just the right amount of leading zeros and other characters to ensure that a solution is found on average every 600,000 or so tries.

However, imagine now that a new computer joins the network, and this one too can compute 1000 hashes a second. This effectively doubles the rate at which the problem can be solved, because now on average 600,000 hashes are tried every 5 minutes, not 10.

Bitcoin’s code elegantly solves this problem by ensuring that every 2,016 times new bitcoin is mined (roughly every 14 days at 10 minutes per block), the difficulty adjusts to become proportional to how much more or less hashing power is mining for bitcoin, such that on average new bitcoin continues to be found roughly every ten minutes or so.

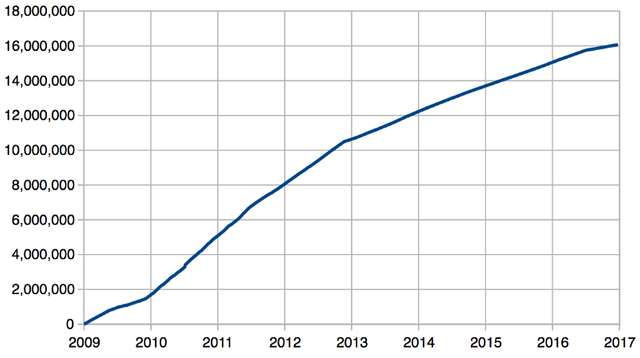

You can see the present difficulty of mining bitcoin here. It should be evident from a half-second glance that the amount of computing power working to mine bitcoin right now is immense, and the difficulty is proportionally similarly immense. As of the time of this writing right now, there are close to 5 billion billion hashes per second being run to try to find the next block of bitcoin.

This system holds a lot of advantages even over gold’s natural system of being mined out of the ground. Gold’s mining is effectively random and not dictated by any perfect computer algorithm, and is consequently much more unpredictable in its output at any given moment. If a huge supply of gold is serendipitously found somewhere, it could theoretically dramatically inflate the rate at which gold enters the existing supply, and consequently cause an unanticipated decrease in the unit price of gold.

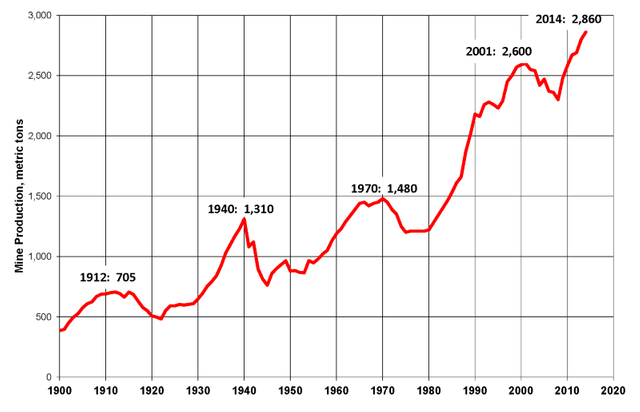

This isn’t just theoretical — it’s the reality of gold production. This graph illustrates vividly the fact that gold production has been dramatically increasing over time, and is today over four times higher than just a hundred years ago.

In fact, more than half of all the gold that has ever been mined in the history of humankind has been mined in just the past 50 years. The difficulty of mining gold doesn’t proportionally increase with the number of people mining it, or with technological innovations that make it significantly easier to locate and mine gold over time.

Bitcoin, on the other hand, will always be mined on a carefully regulated schedule, because it can perfectly adapt no matter how many people begin to mine it or how technologically advanced bitcoin mining hardware becomes.

In fact, it’s already known for certain that there will only ever be a total of 21 million bitcoins in the world.

This is because the amount of bitcoin that is mined every time a hash problem is solved and a new block is created halves every 210,000 blocks, or roughly every 4 years.

The initial reward per block used to be 50 bitcoins back in 2009. After about four years, this dropped to 25 bitcoins in late 2012. The last halving occurred in July 2016, and dropped the reward per block mined to 12.5. In 2020, this should go down to 6.25, in 2024, 3.125, and so forth, all the way until the reward drops to essentially zero.

When all is said and done, there will hence be 21 million bitcoins. Exactly that, no more, no less. Elegant, no? This eliminates yet another risk with extant currencies, gold included: there are absolutely no surprises when it comes to knowing the present and future supply of bitcoin. A million bitcoin will never be found randomly in California one day and incite a digital gold rush.

On top of this, bitcoin is trivially divisible to any arbitrary degree. Presently, the smallest unit of bitcoin is known as a satoshi, and is one hundred millionth of a single bitcoin (0.00000001 bitcoins = 1 satoshi).

This means that unlike gold, bitcoin is perfectly suited to not only being an inflation-proof store of value, but also a day-to-day transactable currency as well, as it is easily divisible to any arbitrary amount. You can buy a cup of coffee with it just as easily as you can buy a car.

Moreover, bitcoin can be sent incredibly quickly and remotely over the internet to anyone anywhere in the world. This is because when bitcoin is mined, the miners are actually providing a service in powering the bitcoin network.

What happens when a miner mines bitcoin is actually that they add a ‘block’ to what is known as the ‘blockchain’. The blockchain is a ledger that contains a record of every transaction ever made with bitcoins since its inception. When someone decides to mine bitcoin, they must download the entire blockchain as it presently stands.

Then, when they successfully find a solution to the next hash problem and mine a block of bitcoins, something magical happens.

They get to add the block they just mined to the end of the existing blockchain — and with it, they include every transaction that was initiated on the bitcoin network since the last block was mined. They then propagate this block they just created to the rest of the network of bitcoin miners, who all then update their own blockchains with this new block, and begin working on solving the next hash problem.

As a reward for providing this valuable service, miners are allowed to add a single transaction to the beginning of the block they mined, called the ‘coinbase transaction’. This transaction contains the brand new bitcoin that was created when they mined the block, and allows the miner to claim this bitcoin for themselves.

At this point, a particularly shrewd reader might become concerned with the fact that the reward for mining a new block of bitcoin gradually shrinks to zero. Won’t this cause miners to stop mining bitcoin, and consequently to stop providing the invaluable service that allows the bitcoin network to function and for transactions to be sent?

The answer is no, because miners are not solely rewarded by the new bitcoin that is generated each time they mine a block.

Users may also send a transaction fee along with their transactions, which is paid out to any miner who decides to include their transaction in a block they mine. Over time, as the bitcoin network becomes used for more and more transactions, it is expected that transaction fees will be more than sufficient for incentivizing enough miners to continue mining blocks to keep the bitcoin network safe, secure, and robust.

It’s important that enough miners keep trying to mine blocks because this is another valuable service miners provide the network. Bitcoin, like gold, is powerful as a store of value because it is decentralized and trustless. There is no one central authority who holds all the power over bitcoin, just like no central authority holds power over gold.

No one person or government can decide to conjure up more bitcoin on demand, or to take it away. The only way the rules that govern bitcoin can be changed is if the software bitcoin miners run to mine bitcoin is changed.

Technically, any bitcoin miner could decide to change the software they run to mine bitcoin at any time. However, this still doesn’t have any impact on changing bitcoin itself. What it would do is cause a ‘hard fork’, or a divergence in the block chain.

This occurs because any block that the rogue miner who changed their software mines won’t be accepted by all the other miners who are still running the original software. Consequently, all the other miners will begin mining different blocks, and adding those to their blockchain. This leads to a fork in the road, essentially, where two completely different blockchains are formed — one by the rogue miner, and one by all the other miners.

Everything up to the point of the software change remains the same in both blockchains, but after that change, the blockchains diverge. Once diverged, they can never be reconciled and remerged.

This isn’t a concern, however, because the bitcoin network runs on consensus, and accepts whichever blockchain is the longest. In practice, this means that whichever blockchain has the most computing power behind it is effectively guaranteed to win, as they’ll be able to calculate the solutions to the hash problems and find new blocks faster than their less powerful competitors.

This does mean that in theory, bitcoin is vulnerable to what’s known as a 51% attack — an attack in which if a single entity was able to gain control of at least 51% of the total hashing power being directed at bitcoin mining, it could outpace a legitimate blockchain and temporarily take control of the network.

This is an extraordinarily difficult feat to accomplish, however, as the more people there are mining bitcoin, the harder it is to take over the network. At the current worldwide mining rate of almost 5 billion gigahashes a second, it would be extraordinarily difficult for even the most powerful organizations in the world (e.g., large-scale governments) to mount a successful 51% attack.

It would be enormously costly, and quite possibly more financially detrimental to the attacker than to the network.

Indeed, the only thing a 51% attacker could really accomplish is destroying collective faith in bitcoin. They couldn’t somehow steal and gain all the value of bitcoins for itself. The attacker wouldn’t be able to generate new bitcoins on demand arbitrarily, and would still have to mine for them. They also would have no control over taking bitcoins created in the past that didn’t belong to them. The only thing they could do, really, is repeatedly spend bitcoin they already owned again and again, but even this is limited in its value, because ‘honest’ miner nodes would never accept these fraudulent payments.

Hence, no rationally self-interested bitcoin miner would ever try to mount a 51% attack, as in all likelihood, they would lose massive amounts of money doing so and gain almost nothing from the effort. The only reason someone would want to conduct a 51% attack is to attempt to destroy faith in bitcoin — large governments, for instance, who might one day feel that their fiat currencies that presently provide them great value to them are becoming threatened by bitcoin. However, the likelihood even of these enormous entities to successfully conduct a 51% attack is already becoming vanishingly small, as mining power increases.

Thus, bitcoin has perfectly utilized recent technological advances to create something heretofore impossible: an extremely safe, reliable, decentralized, and globally transactable digital and better version of gold, and possibly of all types of extant currency at large.

The advantages don’t stop there, however. Bitcoin is also ‘pseudonymous’, meaning that while all transactions ever conducted on the network are public and known by all as everything is recorded in the blockchain, unless someone knows who owns the bitcoins that are being used in these transactions, there is no way to trace those bitcoins and transactions back to a given person or entity.

This serves a dual purpose of both allowing extreme transparency when desired in making transactions, and also allowing a lot of anonymity when desired. If one wants to ensure that they have perfect undeniable proof of their transactions, all they have to do is prove they own certain bitcoins, and then any and all transactions conducted with those bitcoins are undeniably theirs and most certainly occurred.

If one wants, rather, to keep the movement of their money less overt, one simply needs to ensure that the bitcoins they own are never tied to their identities, and that their transactions on the network are obfuscated. This can be accomplished with a variety of methods, such as using a tumbler, which allows one to send bitcoins to an intermediary service that will mix these bitcoins with bitcoins from numerous other sources, and then send bitcoins forward to the intended destination from sources entirely unrelated to the sender’s original bitcoins.

To clarify this a bit more, bitcoins are stored at what are known as ‘addresses’. Think of this as an email address or a mailing address. These addresses allow for the storage, sending, and receiving of bitcoin. The blockchain ledger contains a complete record of the movement of bitcoins from one address to another.

A tumbler allows someone who say, wants to move bitcoins from address 10 to address 100, to instead move their bitcoins from address 10 to a totally random address, say 57. In some other transaction, the tumbler has accepted bitcoins from someone entirely unrelated at say, address 20, who wanted to send the coins ultimately to 200 and sent these instead to another completely random address 42. It then sends the coins stored at address 42 from sender 2 to the address sender 1 originally desired, 100, and sends the coins stored at address 57 from sender 1 to the address sender 2 desired, 200.

This is highly simplified, but effectively how a tumbler works, albeit at much larger scale, and with many more senders and receivers of all sorts of varying amounts.

This ability to transact more anonymously in a digital, global fashion than ever before has indeed opened the gateway to some of bitcoin’s more infamous use cases. Much illicit activity has been enabled by this pseudonymity of bitcoin, including the sale of drugs and other illegal goods online. A more recent development has also been ransomware, whereby malware can now cut straight to the chase and lock up your computer and demand straight up money in the form of bitcoin in exchange for the release of your computer’s data.

These developments have been enabled not only by bitcoin’s pseudonymity, but also the irrevocability of transactions. Unlike current forms of digital payment, such as credit cards and bank transfers, bitcoin transactions are irreversible and do not involve any middleman who can mediate between disputes.

This has its disadvantages, but also its advantages, and was indeed one of the primary benefits the creator of bitcoin (a pseudonymous as-of-yet unidentified figure himself, Satoshi Nakamoto) outlined in the bitcoin white paper. In his own words:

*Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. While the system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust based model. Completely non-reversible transactions are not really possible, since financial institutions cannot avoid mediating disputes.

The cost of mediation increases transaction costs, limiting the minimum practical transaction size and cutting off the possibility for small casual transactions, and there is a broader cost in the loss of ability to make non-reversible payments for nonreversible services. With the possibility of reversal, the need for trust spreads.

Merchants must be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need. A certain percentage of fraud is accepted as unavoidable. These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency, but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party.

What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party. Transactions that are computationally impractical to reverse would protect sellers from fraud, and routine escrow mechanisms could easily be implemented to protect buyers.*

As Satoshi notes, bitcoin’s irreversible, trustless nature removes the need for any middlemen to mediate and broker the process of payments from one person to another. Middlemen (e.g. banks and credit card networks) inherently introduce overhead costs and inefficiency into the system, which make transactions — and micropayments in particular — more costly than would otherwise be the case.

Fraud is also inherently eliminated, as any transaction propagated and confirmed by the bitcoin network by 6 or more blocks is generally accepted to be impossible to ever revoke.

Trustlessness in this sense is a huge component and advantage of bitcoin and cryptocurrency at large. Another ground-breaking innovation the blockchain introduces is the concept of a smart contract, or a contract that similarly requires no trust or middleman to mediate, but is rather contractually executed in a deterministic fashion through code run on the blockchain.

Traditionally, with a legal contract, two parties agree to certain terms with the understanding that if one party reneges, the other party can seek legal recourse with the governmental justice system. Lawsuits, however, can often be inordinately expensive, and in many cases the outcome is far from certain. A good or bad lawyer can make or break a case, and one is also at the mercy of a judge and/or jury and their subjective, possibly mercurial whims. Not the most efficient or foolproof system.

A contract written with and enforced by code, however, removes the need to trust a third party arbitrator (such as a court system), in much the same way that transactions enforced by bitcoin’s code remove the need to trust a third party financial institution. The code is written in such a way that clearly specifies the conditions of the contract, and will automatically enforce these conditions.

For instance, if two parties decide to make a bet on Donald Trump winning the election, historically, this could only be done by either word of honor or by some ad hoc legal contract. For a say, small $100 bet, it would be absolutely a non-starter to pursue legal action in the case that one of the parties decided to renege on the deal in the aftermath of the election. Normally, the reneged-upon party would simply be left in the dust without recourse.

With the advent of smart contracts made possible by the blockchain, however, this is (soon-to-be) a thing of the past. One can create a simple smart contract at effectively almost no cost that specifies in code that each party will send it $100 in bitcoin, and that upon the completion of the election process, it will either send all $200 to the party that bet on Donald Trump winning the election, or send the $200 to the party that bet on him losing the election. No ifs, ands, or buts. The code is clear, objective, and deterministic. Either the contract is fulfilled in one direction, or it is fulfilled in the other. No need to trust the other party in the bet at all, much less a third party to mediate.

Ethereum, as will be noted later (hopefully in another article because my god I never want to write again), takes this concept to the next level and runs with it.

One further benefit to bitcoin is that it is truly yours to own, and you can keep it yourself, without the need for a bank or any other intermediary, and use it just as easily as you might a credit card. This ensures that you won’t fall victim to a banking system collapse brought on by fractional reserve banking or irresponsible government and financial institution fiscal policies in general. It also ensures, however, that no one can take your money from you even on an individual basis, global financial apocalypse aside.

This, like systemic banking failures, is not something most people generally have to worry about 99% of the time. However, in the 1% of cases where this does become an issue, it becomes a very serious issue. Refugees and other victims of persecution and oppression are clear examples of this.

As a refugee, generally, if you hope to escape with your money, you have to carry it in physical form on you, either in gold or in paper currency. This is limiting for a few reasons: one, you can only take so much as you can carry or convert to physical form, and two, physical currencies are exceedingly simple to detect and confiscate.

Again, while this all seems incredibly far-fetched today for most people (but not all, as the present day European migrant crisis has made abundantly clear), it happens much more often than one might expect. A little remembered fact is that the United States itself once outlawed the possession of gold, back in 1933 with Executive Order 6102, and forced all its citizens to relinquish all gold to the United States at a fixed price of $20.67 per troy ounce.

Immediately thereafter, the US Treasury revalued all their gold at $35 per troy ounce for foreign transactions, and in the process reaped an enormous profit at the expense of all the citizens that were forced to give up their gold at fire sale prices.

It sounds incredible, but this is real life. The government threatened to fine anyone caught possessing gold in violation of this order $10,000 ($185,000 today) and throw them in jail for up to ten years. A famous case involved one Frederick Barber Campbell, who had on deposit at Chase Bank over 5,000 ounces of gold (worth over $6 million today), and attempted to withdraw the gold that he rightfully owned. Chase refused to allow him to do so, so he decided to sue Chase for depriving him of his assets.

In response to his lawsuit (this case demonstrates the value of basically everything about bitcoin, from the ability to store your own money to the ability to not rely on the legal system for recourse), Campbell was counterattacked and indicted by a federal prosecutor, and had to defend himself in court for not giving up his gold.

Ultimately, while Campbell didn’t end up going to jail, the government did decide to seize all his gold, and confiscated all $6 million worth of gold from him.

It took a full 40 years, or until 1974, before Gerald Ford signed a bill making it once again legal for private individuals and corporations to own gold within the United States.

This underscores the oft mercurial whims of governments, even well-regarded ones like that of the United States, that most citizens heretofore have been subject to without relief or alternative. Most of the time, things run well enough that we all get by without having to think about this fact too much. Sometimes, however, things do go really, really wrong.

Bitcoin fundamentally changes this equation. Unlike even gold, bitcoin is nigh impossible, when stored correctly, for anyone to confiscate without consent. The addresses at which bitcoin values are stored are protected by ‘private keys’, which can be thought of as a password or a key to a lockbox. Without this private key, it is generally impossible to steal the bitcoins held at the public address to which the private key corresponds. So long as you keep this private key secure, your bitcoins are secure.

With things like brain wallets possible, this means that even in the worst case scenario, you can literally store your bitcoins in your brain and nowhere else, and thereby easily prevent their confiscation. Just yet another fundamental innovation in the evolution of currency that bitcoin has made possible — its fully intangible nature is actually an asset.

The intangibility of bitcoin, however, does seem to hang some people up. It’s sometimes difficult to immediately conceive of how bitcoins could possibly hold value, as these people contend, when they are intrinsically worthless. They are nothing but a concept, backed up by some computer code. Gold is a physical, tangible object that you can hold in your hand. It has real uses in industry and as jewelry that lend it value. Even paper money can be used for kindling or toilet paper if the need necessitates.

Bitcoin, on the other hand, is fully intangible. It is just a concept backed by code, no more, no less. It can’t be used for anything functional besides being transferred in concept to other people as a store of value. How could something like this possibly hold value like other existing currencies?

It’s a good question, and one that underscores just how interesting the concept of money really is, and how rarely we actually think critically about it.

Sure, let’s say that you can’t compare bitcoin to gold and say it’s better because gold has tangible, real-world utility and bitcoin doesn’t.

What is the value of that real-world utility? Only about 12% of gold purchased every year is actually used for industrial and medical purposes. If this is truly where gold’s value is derived from, gold would be worth dramatically less than it actually is.

To the other point, gold’s coveted status in jewelry is merely a derivative property of its perceived value, which leads to its designation as a status symbol. Without that underlying perceived value, it would command far less value in jewelry.

Consequently, the question still remains about the gap between the industrial and medical value of gold and the actual value of gold as determined by the market. Where does the value in that gap come from?

This is even more true of paper currency. Yes, you can utilize and reuse the paper for all the intrinsic value paper has. But what is that intrinsic value of paper? This is easy to answer, because we can just see how much the government pays to make paper money. $1 and $2 bills cost less than 5 cents to make on the low end of the spectrum, while $100 bills cost 12.3 cents on the high end.

Even the $1 bill, which seems to be the best deal if one is valuing the worth of one’s currency based on its intrinsic ‘tangible’ value, has only ~5 cents worth of actual paper value behind it, or <5% of its actual denominated value. Where does the rest of that 95 cents of value come from?

It turns out these gaps in value between the worth of the ‘tangible’ thing itself and the actual value of the currency as it stands on the market today is just as much conjured up out of thin air as a mere concept as bitcoin’s perceived value is.

This ‘intangible’ worth that we ascribe to currency, which accounts for the vast majority of the value of all currencies, not just bitcoin, is ultimately what makes money work. Yuval Noah Harari captures this fact very well in Sapiens, where he lays out the case that the value of a given form of money is essentially an indication of trust in that form of money. It is our shared collective trust and belief in a currency that gives it value, not its intrinsic tangible utility or anything else.

Gold holds its value well because we trust that we will all collectively continue to trust it as a store of value forever, predominantly due to its scarcity and lack of centralized control. Fiat currencies hold their value well when they do because people trust that everyone else trusts the currency as well, and that it is deserving of trust. The moment that collective trust collapses, so too does the currency, no matter what its intrinsic ‘tangible’ value.

This is why no fiat currency has ever stood the test of time over a long enough timescale, whereas gold has to date always stood the test of time and retained its value well. Collective trust for gold has never collapsed because of its inherent scarcity and immunity to the vicissitudes fiat currencies must endure at the hands of capricious centralized governing powers, whereas collective trust in every historical fiat currency has inevitably failed to date, and collective trust in many present-day fiat currencies continues to fail as we speak.

With this in mind, bitcoin can arguably be seen as the purest form of money, as its value is entirely predicated on trust in it, and nothing else. It can arguably also be seen as the most trustworthy of currencies, as it was bespoke made by intentional design to exhibit all the best elements of historically trustworthy currencies (e.g. gold), as well as to introduce for the first time a number of characteristics that make it even better than all previously extant currencies.

If people have trusted gold to date as a store of value because of its inherent scarcity and resistance to centralized control and price/supply manipulation, bitcoin does all that and more, and does it all better. Gold’s scarcity, as illustrated above, is anything but constant, and we’ve more than doubled our world’s supply of gold in just the last 50 years. Bitcoin, on the other hand, has a precisely and publicly known proliferation schedule, and will approach the limit of its supply in just a few more decades.

As a thought exercise, imagine a new fledgling nation called the United States came into formation and decided to create their own fiat currency today. At the same time, bitcoin is introduced as a currency.

Which would you trust? My personal bet would be absolutely, wholly, and unequivocally bitcoin. With the new US currency, I would be effectively required to trust that the US government would act without fail over the entire course of its indefinite existence to practice perfect fiscally responsible habits and not screw up its economy in any dramatic ways. I would also be aware that even under perfect circumstances, the currency would be fundamentally designed to inflate, and consequently my money would continue to lose value over time if I decided to hold and save it.

Furthermore, I would be forced to use an intermediary financial institution such as a bank to hold my money for me, and thereby expose myself to yet another layer of required trust and accompanying risk. I would also be aware that these institutions would almost certainly practice fractional reserve banking to the maximum extent they could get away with it, such that they would be extremely fragile to small perturbations and vulnerable to things like bank runs and runaway systemic banking collapses.

On the other hand, with bitcoin, I wouldn’t have to trust anyone at all. I would know for certain that my coins wouldn’t lose their value due to inflation as a consequence of their designed and indelible scarcity. I would also know that as I stored my coins myself, no one else, not even a bank, could actually go and spend 90% of my money, and fail to give it back to me in the event of a bank run. Furthermore, no one could forcibly confiscate my money under any circumstances, as I could always store it in such a way that it could never be retrieved except with my consent. No one would even necessarily be able to know how much money I held, unless I chose to make that information public.

Remember: just 13 years after its inception, the US currency had already suffered fatal runaway inflation and collapsed. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is worth more than ever just 9 years after its inception, and currently boasts a market cap of over $40 billion.

Which would you trust?

The other common argument against bitcoin is that it is useless for any real world functions right now besides ransomware and illegal activities, and is therefore worthless because it has no good use cases.

This is a fundamentally flawed argument that can be lobbied against absolutely any new technology or invention, and fails to take into account the natural process of growth and gradual adoption over time. The exact same argument was used against the internet in its early days, and I find this article from Newsweek, published in 1995, particularly illuminating in this regard.

*After two decades online, I’m perplexed. It’s not that I haven’t had a gas of a good time on the Internet. I’ve met great people and even caught a hacker or two. But today, I’m uneasy about this most trendy and oversold community. Visionaries see a future of telecommuting workers, interactive libraries and multimedia classrooms. They speak of electronic town meetings and virtual communities. Commerce and business will shift from offices and malls to networks and modems. And the freedom of digital networks will make government more democratic.

Baloney. Do our computer pundits lack all common sense? The truth in no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.*

What’s striking in this is that while everything he said at the time was true, and certainly none of those things were particularly possible back in 1995, it all came to pass eventually. Today, remote workers are a huge part of the global workforce. Online education is booming. Amazon is taking over all of commerce and is larger than any retail store in the world. Print newspapers and magazines are dying left and right, replaced by a proliferation of online news.

The same growth trajectory is how I see bitcoin, cryptocurrency, and blockchain technology at large playing out. If all goes well — and there’s no guarantee it might, everything indeed might fail and all our hopes and dreams might gang aft agley — there’s no reason at all that bitcoin can’t one day surpass even our wildest imaginations today, just like the internet did before it, and fundamentally rewrite the script for how we interact with money and the world as a whole.

Yes, today, it is far from this goal, but even now, we make progress in pushing forward the utility of bitcoin in every day pragmatic life. Already, it has proved indispensable to myself and hundreds of thousands of people around the world. I pay many of my employees today in bitcoin, even, because several of them live in Eastern Europe where they’re subject to draconian capital controls.

Were I to send them a wire (as I used to), their banks demand a mountain of documentation detailing every last dollar and hold their money for upwards of half a month before ultimately releasing it to them. Naturally, this is a pain in the ass and highly inefficient, time consuming, and resource intensive for all of us. Bitcoin easily sidesteps all of these issues.

Bitcoin is also dramatically cheaper to use than almost any other form of international money transfer today. Already, for this use case alone, it proves its worth over current dominant international money transfer solutions, such as Western Union. I can transfer money to anyone in the world, in any amount, and have them receive it without moving a finger in just a few minutes. For this privilege, I have to pay just a few cents, no matter how much I’m sending, instead of a huge proportional percentage, with hefty minimum fees and surcharges.

It’s also extremely convenient and valuable for a merchant to use, and we had great success implementing it for a trial run at my company Sprayable back in the day. In the past, we’ve suffered from rampant fraud after our site was targeted on a carding forum (a place where people buy and sell and use stolen credit cards). When we were paid in bitcoin, however, these concerns were completely eliminated, as fraud is an impossibility on the bitcoin network with enough confirmations.

This is only the beginning. You don’t expect a horse to become a world champion racer straight from the womb. It takes time, training, and a fair bit of luck. The same is true of bitcoin and blockchain technology. But just because a horse may not be a world champion just quite yet, it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t bet on that horse in the long run. If you see potential in that horse, and are willing to wait it out for the long run, go ahead, bet on that horse. One day, it might just take over the world, and if it does, you might just win big.

Part II will follow!