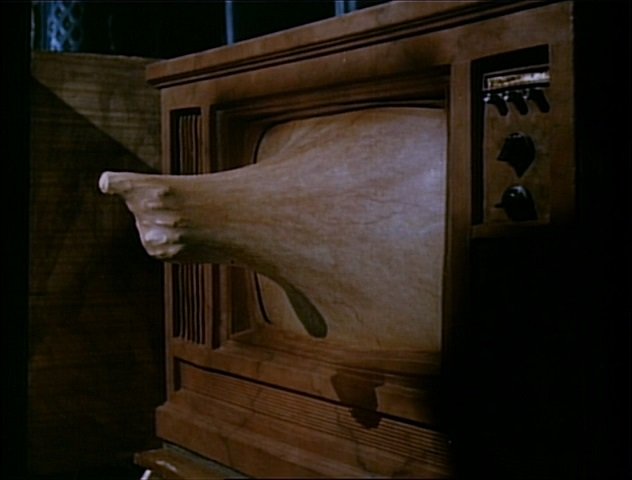

Screenshot from the trailer of the film Videodrome (1983). Public domain.

"Some [creators/distributors of 'deepfake' pornography," Nina Jankowicz writes at The Atlantic, "seem to believe that they have a right to distribute these images --- that because they fed a publicly available photo of a woman into an application engineered to make pornography, they have created art or a legitimate work of parody."

Jankowicz, who served as Executive Director of the federal government's now-defunct "Disinformation Governance Board," has good reason to be upset with the phenomenon of deepfake porn. She recently discovered that she's been a subject of it. That's presumptively both discomfiting and disgusting. I don't blame her for not liking it one bit.

But creepy as deepfake porn --- essentially using software to e.g. put a recognizable facsimile of a person's head "on" the body of an actor in a pornographic video --- may be, it's inescapably fiction and expression, and entitled to the same protection as other fiction and expression.

The title of Jankowicz's piece is "I Shouldn't Have to Accept Being in Deepfake Porn." She DOESN'T have to. It doesn't matter whether she does or not, because she isn't in the porn. A photo of her --- in fact, an official US government portrait that's in the public domain --- is.

Jankowicz supports legislation that would "provide victims with somewhat easier recourse when they find themselves unwittingly starring in nonconsensual porn."

But "nonconsensual porn" would consist abducting people and forcing them to engage in sexual acts on camera. Jankowicz willingly sat for a photo that belongs to "the public" to do with as we wish.

Not everything disgusting violates rights, and only things which violate rights should be treated as crimes, or even actionable torts.

A 1996 Joe Klein novel and 1998 film, Primary Colors, featured characters who were, recognizably, Bill and Hillary Clinton and members of the Clinton inner circle. They're portrayed as engaging in actions which may or may not have actually happened in real life, some of which arguably, to grab a Supreme Court ruling expression, "appeal to a prurient interest."

Librarian Daria Carter-Clark, who had good reason to believe that one of the characters portrayed as having engaged in a sexual fling with the Bill Clinton character was based on her, sued for libel. She lost. Romans-a-clef --- works in which real-life people and events are given fictional treatment --- enjoy the same constitutional protections as other fiction.

And that's exactly how it should be.

There are certainly some sick puppies out there, doing some sick things. We don't have to like that, and it's completely understandable when those targeted by such things feel wronged and damaged. But until and unless those sick puppies cross the actual line of coercion or violence, the only legitimate tool for changing their behavior is persuasion.