What DNA Testing Companies’ Terrifying Privacy Policies Actually Mean

You probably wouldn’t hand out your social security number without having a pretty good idea of how that information was going to be used, right? That would be dumb. It’s extremely sensitive information. And yet, the consumer genetic testing market is booming thanks to people readily giving up another piece of their identity: their genetic code.

Ever-cheaper DNA sequencing technology has allowed genetic testing to become far more than a tool for doctors. Genetic testing has become entertainment, with companies offering tests that provide insight into ancestry, athletic ability, sleep habits and much more. The consumer genetic testing market was valued at $70 million in 2015, but estimates expect it to expand to $340 million by 2022.

When you spit in a test tube in in hopes of finding out about your ancestry or health or that perfect, genetically optimized bottle of wine, you’re giving companies access to some very intimate details about what makes you, you. Your genes don’t determine everything about who you are, but they do contain revealing information about your health, relationships, personality, and family history that, like a social security number, could be easily abused. Not only that—your genes reveal all of that information about other people you’re related to, too.

Despite all that, we’re guessing that when you signed up for Ancestry or 23andMe, you probably didn’t read the fine print to find out what, exactly, those companies plan to do with your data. We can’t blame you—they’re long, boring polices written in legalese that’s difficult to understand. If you actually read those policies, though, you might not have gone ahead with the test. It turns out that the breadth of rights you are giving away to your DNA is kind of terrifying.

Lucky for you, Gizmodo slogged though every line of Ancestry.com, 23andMe, and Helix’s privacy, terms of service, and research policies with the help of experts in privacy, law and consumer protection. It wasn’t fun. We fell asleep at least once. And what we found wasn’t pretty.

“It’s basically like you have no privacy, they’re taking it all,” said Joel Winston, a consumer protection lawyer. “When it comes to DNA tests, don’t assume you have any rights.”

In general, it’s always a good idea to read the terms before you click. But because we know there’s a good chance you won’t, here’s what you need to know before giving away your genetic information.

Testing companies can claim ownership of your DNA

Okay, so your DNA is inside of you. A corporation can’t really claim ownership of it. But they can claim ownership of the DNA sample you send them, and the analysis they run on it, including the resulting information on the makeup of your genome.

When it comes to Ancestry, while the company recently revised its policy to state that it “does not claim any ownership rights in the DNA that is submitted for testing,” another clause in its policies asserts that even if they don’t actually own your DNA, the company can use that DNA basically however it wants:

“By submitting DNA to AncestryDNA, you grant AncestryDNA and the Ancestry Group Companies a royalty-free, worldwide, sublicensable, transferable license to host, transfer, process, analyze, distribute, and communicate your Genetic Information for the purposes of providing you products and services, conducting Ancestry’s research and product development, enhancing Ancestry’s user experience, and making and offering personalized products and services.”

If that language sounds scary, that’s because it is.

“This is a huge red flag,” said Winston. “Even though Ancestry says they don’t really own your DNA—which is true, because they can’t take it from you—they now own rights to it. They could test it in a 100 years from their freezer for whatever purpose they want.”

In response, an Ancestry spokesperson emphasized to Gizmodo that AncestryDNA does not claim ownership rights to customer DNA. When pressed, though, the spokesperson conceded that it is “broadly correct” that the license it claims on your data allows the company the perks of ownership.

“We couldn’t send samples to the lab to be analyzed, transmit the results, etc. if we didn’t have a license,” the spokesperson said. “None of that supersedes the fact the we don’t, and will not, share data for research or commercial purposes with third parties without a customer agreeing to an Informed Consent. If they don’t want us to have a license any longer, they can delete their account or ask us to delete their data. If they don’t want their data shared, they can decline the consent.”

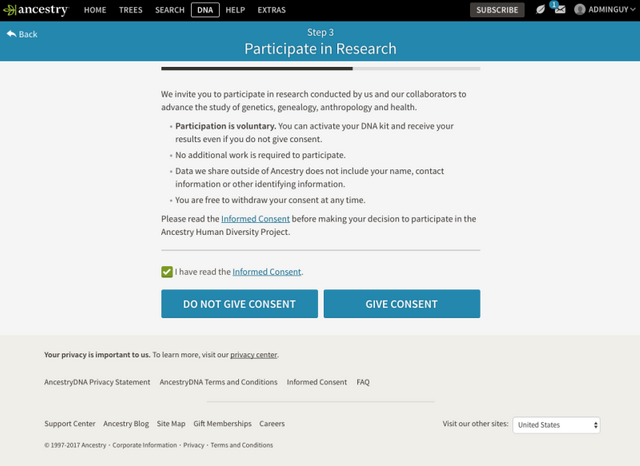

The Informed Consent screen. Screenshot: Ancestry

You don’t have to consent to participate in research. But for both 23andMe and Ancestry, it’s worth noting, the informed consent document only shows up once someone is registering a kit that’s already been purchased. And it only applies to sharing of your data with third parties like pharmaceutical companies and universities for research—not the ways in which companies may seek to use your information to improve its own business.

Ancestry isn’t the only company to contain a clause claiming a broad licenses to your data, either. Earlier this year, the DNA testing firm Helix launched a DNA analysis platform on which consumers can buy DNA “apps” from several different companies. Some Helix partner company policies contain similar phrasing.

“I would never sign away the rights to my genes,” said Petter Pitts, the president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest and a Former FDA Associate Commissioner. “You shouldn’t either.”

It’s unclear who has access to your DNA, or for what

All of the DNA testing policies that Gizmodo reviewed made it clear that genetic information is shared within the company and in certain circumstances with third parties for research and business purposes.

“The primary ways we use genetic data are to provide services to our customers, perform product research and development, and, as necessary, for quality control activities,” 23andMe privacy officer Kate Black told Gizmodo.

What’s not clear is who all of those third parties are and what kinds of rules the companies put in place to prevent those third parties from abusing the access to genetic information.

Ancestry shared with Gizmodo a link on yet another part of its website to its list of research collaborators, emphasizing that Google’s Calico is the company’s only commercial partnership. 23andMe, likewise, provides a list of at least some of its research partners, which include the drug companies Pfizer and Genentech. The companies all also utilize contractors for services such as business analytics and lab work, though, and the names of those providers or which ones have access to genetic information are not readily available anywhere online. (23andMe told Gizmodo that the only contractor that actually has access to genetic information is their lab contractor, Lab Corp. The company said this information isn’t posted online, however, because customers don’t ask for it.)

“They’re handing over your information to someone else and when they do they’re disclaiming responsibility for it and you could never find out who those third parties are,” said Winston.

Pitts also pointed out that if a genetic testing company was bought, there’s no telling how a new owner might handle the data.

“If you don’t like your pictures copyrighted by Facebook, how are you going to feel about your genetic code being bought by one company, then bought by another and all the sudden used for things you never realized?” Pitts told Gizmodo.

The other thing that’s clear is that genetic testing companies are definitely selling information to third parties for medical research in order to make money.

“Using this information for clinical trials is a good thing,” said Pitts. “But do you want some third party organization selling that information to pharmaceutical companies? How secure is your data in that third party environment? You don’t know.”

And in the case of Helix, each DNA “app” customers buy has its own separate policies from different companies. “The precedent for platforms—like the App Store—is not to have one uniform policy for all products,” policy director Elissa Levin said in an emailed statement. “We have created standards and guidance for partners and encourage alignment in their policies.” In other words, Helix has suggested that the companies that offer DNA testing on its platform abide by certain broad guidelines, but no one is enforcing them.

Not to mention, while the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act allegedly prevents health insurers and workplaces from discriminating based on your genetic information, gaps in the law mean that life, long-term care, or disability insurance providers as well as the military can still make decisions based on findings from your DNA.

“GINA actually provides very little protection,” said Ellen Wright Clayton, a lawyer and professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University.

And if you choose to share your genetic information with your doctor or others, it may be used against you and impact the coverage you receive. Worse yet, as 23andMe states bluntly in their Terms of Service: “If you are asked by an insurance company whether you have learned Genetic Information about health conditions and you do not disclose this to them, this may be considered to be fraud.” Genetic testing companies may promise to not share information with insurers without your consent, but that doesn’t stop an insurer from asking you whether you have ever taken any genetic tests. And if the answer is yes, you could be compelled to share information relevant to your health. (A new health care bill and seemingly stalled legislation introduced last March in the house both further threaten to challenge protections that allow you to keep your genetic information private.)

Your anonymous genetic information could get leaked

Recently, a study found that common, open-source DNA-processing programs are super vulnerable to hackers. While the study didn’t mention software specifically used by consumer testing companies, all of the companies mention the possibility of a breach of the company or those unnamed, innumerable contractors in their policies.

And because consumer genetic testing firms are not typically bound by HIPAA, the flow of your data is basically unregulated, said Bob Gellman, a privacy and security consultant. That means any authorized recipient of your information could easily pass it along to someone else.

“Any data anywhere can be hacked in one way or another. That just happens today,” said Gellman. “The more people have the same data, the more there’s risk to the data. That’s just a given.”

Even if the company doesn’t get hacked, your information could be exposed. If you sign on to allow your genetic information to be used for research, you could be identified even if your information is stripped of any “identifying details.”

As Ancestry.com puts it:

There is a potential risk that third parties could identify you from research that is made publicly available, for example if published in a scientific journal. Genetic Data is not typically published, although it is sometimes made available for review by peer scientists, journal editors or others. Although we remove common identifying information (such as your name and contact information) from any Data before publication, Genetic Data is different from other data because it can be used as an identifier in combination with other information. It is not currently common to do this but it can be done, particularly if genetic data about you or genetic relatives is available from other public genetic databases. In the future, new methods for this may be developed and it may become more common.

In other words, anonymizing your data still doesn’t guarantee someone won’t figure out who you are. In fact, researchers have already shown that it is possible to identify some people based on anonymous genetic data. In 2013, an MIT professor published a study in which he successfully identified people and their relatives based on “anonymous” genetic data in a research study, along with only their age and a state. 23andMe pointed out that it would be unusual for information like age and location to be shared, even with researchers. But the study demonstrated how difficult it is to anonymize information that is inherently linked to your identity to begin with.

If you sue and lose, you’re screwed

Way down in the fine print, 23andMe spells out a policy that basically makes sure the company will never get sued, ever: If you sue them for something (like maybe screwing up your test), and lose, you would be responsible for the possible millions of dollars in legal fees accrued by 23andMe.

As the company puts it:

“Any Disputes shall be resolved by final and binding arbitration under the rules and auspices of the American Arbitration Association, to be held in San Francisco, California, in English, with a written decision stating legal reasoning issued by the arbitrator(s) at either party’s request, and with arbitration costs and reasonable documented attorneys’ costs of both parties to be borne by the party that ultimately loses.”

“It’s a threat in advance,” said Winston. “In one sentence, 23andMe destroys access to the normal rule of law, forcibly imposes mandatory arbitration, and, issues a clear threat—if the individual loses in arbitration, she must pay for 23andMe’s lawyers! Insane.”

23andMe declined to comment on the binding arbitration clause.

If companies get rich off your DNA, you get nothing

Essentially, you are buying a test from genetic testing firms so that they can then make more money by selling your DNA for research purposes. The hope is that important discoveries—say, a gene responsible for Alzheimers—come from all this information. But if your DNA is the golden ticket, all of the companies have terms that say you get zip.

“There’s really no very good reason to do a consumer DNA test,” said Winston. “But people at least need to know what they are signing up for. These companies need to say outright, ‘You’re giving us your information and we can do with it whatever we want.’”

Kate Black, of 23andMe, told Gizmodo that the company goes to lengths to make sure people understand the weight of the decision they are making.

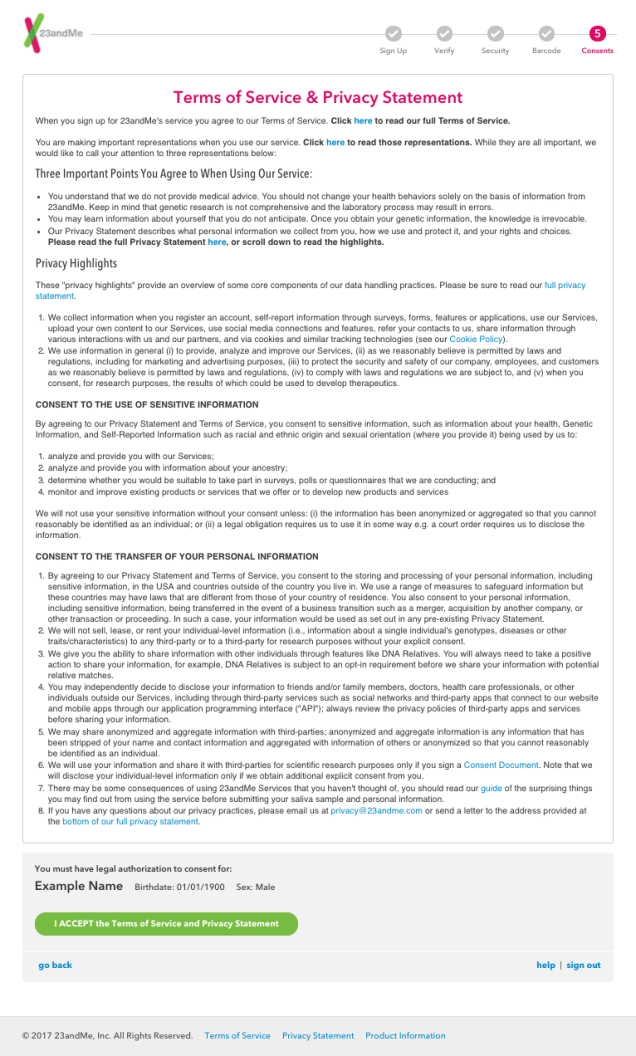

23andMe does go further than other companies, showing customers key bullet points from their policies in plain language without having to click through to another screen full of legalese.

“It’s important to surface crucial information at the time individuals are making decisions about participating in our service,” Black said.

But it would be impossible for a few bullet points to convey the wide swath of privileges consumers are giving companies when they send them a spit tube full of DNA. To give credit where it’s due: If you can actually click on the tiny fine print links while registering your DNA testing kit and stay awake through all of the company’s legal documents—and you really, really should—all of these companies do outline many of the risks of sharing your DNA with them.

But Pitts said he would like to see more companies start by doing what 23andMe does, and provide an overview of policies on the same page where users must check the box saying they understand the policy. He also said he’d like to see companies disclose the name of every other organization that touches consumer’s genetic information, and better disclose the measures put in place to make sure those third parties are keeping data secure.

“Something as important as your genetic markers shouldn’t be thrown around lightly,” said Pitts. “With all the best intentions, checking a box does not mean that your info is accurate or safe or protected.”

If you do not read those documents—and many don’t—you’re missing the fine print that explains how your DNA can be used, misused, leaked, hacked, sold and commodified without your knowledge or deliberate consent.

Not indicating that the content you copy/paste is not your original work could be seen as plagiarism.

Some tips to share content and add value:

Repeated plagiarized posts are considered spam. Spam is discouraged by the community, and may result in action from the cheetah bot.

Creative Commons: If you are posting content under a Creative Commons license, please attribute and link according to the specific license. If you are posting content under CC0 or Public Domain please consider noting that at the end of your post.

If you are actually the original author, please do reply to let us know!

Thank You!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

http://bestsellermagazine.com/news/Privacy-Policy-&-Cookies

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit