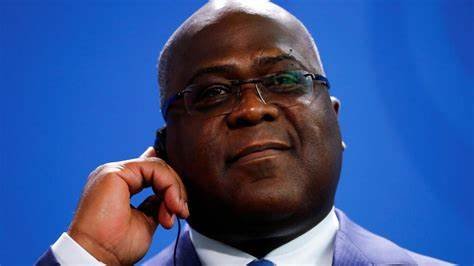

DR Congo President Felix Tshisekedi at a news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel (not pictured) in Berlin, Germany November 15, 2019. © Fabrizio Bensch, Reuters

https://digg.com/@30-jours-max-film-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@twist-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@wonder-woman-1984-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@john-wick-parabellum-2019-film-complet-fr

https://digg.com/@malcolm-and-marie-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@one-piece-stampede-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@megan-is-missing-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@the-dig-2021-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@sultan-kntl

https://digg.com/@meretek-again

https://digg.com/@le-tigre-blanc-streaming-vf-fr

https://digg.com/@dayana-anjim

https://digg.com/@vostfr-film-les-tuche-4-en-france-2021

Two years after his election, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi has finally taken control, loosening his predecessor Joseph Kabila’s seemingly indestructible iron grip on power behind the scenes.

It seemed impossible for Tshisekedi to climb out from underneath Kabila’s shadow when he acceded to the top job in January 2019 – one month after coming out ahead in presidential elections amid doubts from electoral observers that he had really won more votes than Kabila’s arch-rival Martin Fayulu.

Tshisekedi had little room for manoeuvre: in power since 2001, Kabila had tightened control of DR Congo’s major institutions: the army, the intelligence services, the constitutional court and the electoral commission. Kabila’s party the Common Front for Congo (FCC) controlled two-thirds of parliamentary seats, forcing Tshisekedi to form a coalition government with his own party in the minority.

But two years later, Tshisekedi has managed to loosen Kabila’s lingering grip. The pro-Kabila head of the Senate resigned on Friday as MPs prepared a censure motion against him. Then the vast majority of FCC MPs switched their allegiances and joined Tshisekedi’s new political group the Sacred Union, giving it a large majority in the lower chamber.

‘Never any trust’

These MPs pushed out pro-Kabila Prime Minister Sylvestre Ilunga Ilunkamba with a censure motion on January 27 – a month after they ousted the head of the National Assembly.

“There was never any trust between Tshisekedi and Kabila,” said Trésor Kibangula, an analyst at research foundation the Congo Study Group. “Each side has always been trying to diminish the other.”

Hence a year and a half of backbiting and power plays followed Tshisekedi’s inauguration. In 2020 the president’s camp banned some Kabila family members, including his once-powerful twin sister Jaynet, from travelling. Tensions rose to boiling point in July, when Tshisekedi appointed three new judges to the Constitutional Court amid the then prime minister’s absence. Kabila’s camp was outraged and refused to attend the swearing-in ceremony. In early December, Tshisekedi announced the end of the ruling coalition that combined his presidency with an FCC-controlled parliament.

Tshisekedi had already prepared for this. His camp set up meetings in the summer to persuade Kabila supporters to back him. “We set out to bring disillusioned FCC MPs to our side,” said an anonymous member of Kabila’s camp.

Anger had been brewing there for several months. “The FCC was controlled by a clique who didn’t want to see new people rise to the fore,” said MP Patrick Munyomo, who has joined the Sacred Union.

In December, Tshisekedi threatened to dissolve the National Assembly if he did not get a majority – causing many MPs to worry about losing their jobs. “It was a good move, psychologically,” said MP Nsingi Pululu.

Tshisekedi and his allies deployed the carrot after this deft use of the stick. The head of his party the UPDS, Jean-Marc Kabund said he would “look out for the interests” of MPs defecting from the FCC.

“Many of them left out of opportunism, keen to get jobs,” said Marie-Ange Mushobekwa, a member of the FCC’s pro-Kabila “crisis committee”.

“I didn't ask for a job – but I hope I get one,” Pululu said.

A range of corruption allegations emerged against both sides amid the defections – with each side accusing the other of “buying” parliamentarians with bungs of thousands of dollars and 4x4 cars.

“It is going on, although I refused to accept anything,” one FCC defector said. “I’m not saying there haven’t been any bank notes going around, but we haven’t been buying people’s consciences,” said a senior member of Tshisekedi’s camp.

Kabila redux?

Kabila has remained silent throughout this process. Since the dismissal of close ally Jeannine Mabunda as head of the National Assembly, he has been living in his farm in Katanga province near the Zambian border, far away from the political turmoil in the capital Kinshasa.

He had warned Tshisekedi that the National Assembly is a red line, but realised that “he’s not capable of reacting yet”, Kibangula said.

Kabila remains a powerful figure in DR Congo. He and his family control a nexus of more than 80 companies operating in almost every sector of the economy. Gécamines – the country’s largest mining company and biggest contributor to the state’s budget – is headed by one of the ex-president’s most loyal lieutenants, Albert Yuma.

Meanwhile Kabila enjoys significant support within the rank and file of the army and intelligence service: “Tshisekedi has more and more backing within the security forces, but it’s still not much compared to the support for Kabila,” Kibangula said.

With more than 100 MPs remaining loyal to the ex-president, the FCC is becoming DR Congo’s main opposition force. This would provide a springboard for Kabila to leap back into the fray. “Kabila has not left the world of politics,” said FCC spokesman Alain Atundu. “We’re now starting to put a battle plan in place.”

This article has been translated from the original in French.

DR CONGO

FELIX TSHISEKEDI

JOSEPH KABILA

AFRICAN POLITICS