If you haven’t heard, Amazon won ecommerce. Bezos’ juggernaut is the most powerful marketplace and brand the Western world has ever seen (get my analysis here as an ex 7 figure Amazon seller).

But it isn’t the only game in town.

Every year new startups appear, looking to compete and grab their piece of the pie. As an ex-Amazon seller (and host of a top Amazon podcast), I can say for certain that the majority of the action in ecommerce is on the brand side. It gets easier and easier to source and manufacture product and put your label on it.

These businesses ARE NOT fundable. There is no disruptive innovation, there is no world shattering business or venture scale profits in the pipeline. That is fine.

But if you are here, you want to go big. You’re an investor or an operator interested in venture scale ecommerce and looking for an edge.

There are two fundable categories of ecommerce: marketplaces and ecommerce brands. To date, the majority of the money and returns have been via marketplaces. Look no further than Amazon, Ebay and Etsy.

(NOTE: SaaS/Shopify for ecommerce merchants was not included in these categories as it is a B2B SaaS play.)

When it comes to marketplaces, I have covered the topic extensive. I will link to these articles here to avoid repeating myself.

- The Cult-Like Religion of ICOs and End of Amazon?

- The 5 Types of Network Effects and How to Hack Them

Brand’s business models are getting more interesting, lets take a look.

There are 4 types of disruptive ecommerce businesses:

- Direct to consumer brands

- Subscription companies

- Delivery companies

- Experiential commerce companies

Let’s look at each of these, their outliers and what the future holds.

Direct to consumer brands

Recently, mega companies have been created by disrupting traditional supply chains.

Brands like Casper, @Harry’s and Warby Parker are leading the way. These direct-to-consumer brands cut out the middlemen by selling online and owning manufacturing to give customers better value for their money. So while consumers save a ton; the brands get to boost their margins (fewer mouths to feed), control their supply chain and build defensibility into their business.

They all take it a step further as well. The brand becomes the experience.

Casper delivers a mattress in a box. Then it inflates automatically and ready to use. How cool is that.

Source: Casper

And Harry’s and Warby Parker deliver premium products and a premium experience at pretty affordable price. Their focus on brand keeps consumers coming back because customers love their products. And their NPS and word of mouth work wonders for marketing (Warby Parker — NPS: 91) (Source: NPSBenchmarks.com)

But not all DTC brands are successes. The vast majority fail. The reason is the model. Casper isn’t valued at $750M+ because of their mattresses. The company succeeded because the industry was broken.

Buying mattresses is incredibly inefficient. You go to a mattress store, try a ton of beds, spend a bunch of time and have a sleazy salesman trying to sell you. Plus retailers needed a heck of a lot of inventory.

Casper flips the model on its head. There is no distributor/wholesaler and no retail store. By avoiding overhead, middlemen and excess shipping costs, Casper creates a truly unique and valuable experience. And to top it all off, there is a free 100 night sleep trial.

What other company gives you 3+ months to try out a product, especially one you have sex on? Which is another thing the brand does different.

“It’s specifically designed and optimized for great sex as well as great sleep” — The Washington Post

Playing to your strengths with engaging, alternative branding builds buzz — something all of these companies succeeded at.

The problem with direct to consumer brands

Too many startups today try to be Casper for X or Warby Parker for Y… it doesn’t work. Warby was successful because of the broken luxury eyewear market. It was expensive and not democratized. They cut out costs while increasing quality and built a killer company.

But this approach fails in most areas. If an industry is not “inefficient enough”, a direct to consumer model will not work.

Startups need a 5–10x improvement to displace the incumbent. Saving Joe Schmo 10% rarely results in unicorns.

Things to look for when starting a DTC brand:

- Category with high gross margins and medium to big ticket items — these allow for greater CAC (customer acquisition costs)

- Category with few entrenched incumbents dominating industry — likely means market costs are inflated with significant room to price cut

- Product line where barriers to entry are very large (think massive minimum order quantities or tooling costs)

- Products with some repeat purchasing behavior — reorders really drive LTV

- Relatively small product line — the fewer skus you sell, the lower the costs and easier it is to focus/improve

If brands don’t check at least 2–3 of those boxes, they will likely will have trouble. The last thing you want with a DTC business is lookalike competition right out of the gate.

Subscription companies

While DTC companies can also offer subscriptions, the majority of subscription box companies do not own their supply chain.

Throughout 2015 and 2016, subscription businesses were hot. Companies like Blue Apron, Birchbox, Trunk Club and Dollar Shave Club raised~$462M to date, and they are by no means the only ones.

Subscription companies are sexy. The recurring revenue is like SaaS with physical products. This is incredibly rare in retail/ecommerce, hence the excitement.

The problem with subscription companies

Lately these companies have come under fire. According to Recode, Blue Apron is the worst performing IPO of 2017, at a valuation just 59% of their previous round.

Source: BusinessInsider

Source: BusinessInsider

The problem: churn and unit economics. Delivery businesses are cost intensive, which is why Blue Apron’s raised ~$200M to date (excluding IPO). And all is fine and well when LTV projections hold. But what happens when they don’t?

The meal kit delivery space is increasingly crowded. Even Amazon is getting in on the action. Even though the company created demand where it previously did not exist, users are switching to cheaper providers or passing on meal kits entirely. That spells trouble.

A similar problem occurs in fashion. You only need so many shoes. More and more isn’t appreciated and eventually becomes problematic. So how long do you stick around?

This is where predictable, repeat purchasing comes into play. This is why DSC has been so successful. Men need to shave, it is that simple. Acquire a customer and you can potentially keep him for life (hence why Unilever paid $1B to acquire DSC)

Repeat buying behaviors are sacred for subscription companies. Ones that do not tap repeat buying behaviors are toast.

Things to look for when starting a subscription business:

- Product with significant repeat purchasing behavior, ideally consumable in nature

- Category with few innovations & startups

- Product line where barriers to entry are very large

- Potential upsells and re-monetization strategies

Delivery companies

As an angel investor, I would avoid these. Delivery is a race to the bottom. There is no value and few ways to differentiate. If you get my food here 5 minutes faster or $2 cheaper, I’ll use you every time.

Customers do not care who is delivering: Uber, Instacart, Amazon… it is all the same.

In essence delivery companies are supply and demand aggregators. Companies like Instacart (groceries) and DoorDash (takeout) rush food to you fast.

There is a problem though. Supply is not proprietary. What prevents PizzaHut from offering delivery or adding their menu to GrubHub? (Or Amazon from acquiring Whole Foods, Instacart’s #1 offering — More on the implications of Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods here)

The answer of course is nothing. And a business built on paying to acquire customers without any kind of moat is a sand castle that slowly sinks.

These businesses were hot for a time but the unit economics, like subscription startups has failed to follow through. Competitive pressures drive down prices and margins.

No one wins in a race to the bottom.

And even for companies breaking even or making money, what prevents competitors with cash from bidding them into oblivion (this is the same problem with Uber’s business model, detailed here)

BONUS: For more, here is an interview I did with Semil Shah, investor in Instacart and DoorDash on the future of ecommerce and retail.

Experiential commerce

Last but certainly not least is experiential commerce. In my opinion this is where the money lies. The future isn’t about small changes to the past, it is about reinventing what it means to shop.

There are two categories of experiential commerce: local and virtual (both real and virtual), both are interesting.

And many startups are looking into the local commerce concept and applying it to ecommerce.

Local commerce

Companies like Warby Parker and Amazon are actually building out retail stores as the rest of retail dies. And it makes sense. Being closer to customers allows brands to more efficiently grow with and understand their customers.

This is a flip flop of traditional shopping. Today you go to the store, try out a phone at Best Buy and buy it online, in the store, from Amazon.com. You save 11% and got a chance to try it before you buy it. You are happy, Best Buy isn’t.

Why fight customer behavior? Amazon recognizes the value of window shopping and trying things out. Lure a customer into a store with a one-click checkout and average order size will increase.

Retail brands need to follow suit. Reduce footprint, increase online stock and start selling. Unfortunately it is not that easy — which is why most will die.

This creates an interesting opportunity for startups and investors though. As large companies see the end in sight, they fight tooth and nail to survive. Often that equates to buying startups. Look at General Motors’s $1B acquisition of Cruise Automation or Ford’s investment in Argo AI. The incumbents will pay big bucks to save their skin.

Things to look for when considering local retail ecommerce:

- Products with large cost to size/weight ratios

- Category with high gross margins and medium to big ticket items — these allow for greater CAC (customer acquisition costs)

- Category with few innovative competitors

- Product line where returns are high without trying product first

But big box retailers can do this too. Cooking classes in Kroger, a senior citizen electronics class at BestBuy, dog care classes at Petco… there are ways for retail to save itself. Unfortunately understanding the customer and creating experiences is harder than offering yet another flash sale.

Death by a million deals…?

Virtual real world commerce

The future of commerce surely isn’t all local. Many are betting big on VR and AR for enhanced online shopping.

When shopping for furniture, nothing beats seeing the sofa in your home — except a virtual world where you walk through an infinite IKEA from anywhere that seamlessly tailors itself to your tastes.

There are tons of ways these trends can play out with value creation from many angles. As a rule of thumb, I prefer picks & shovels businesses — products or services that help other businesses succeed. As such, I am interested in marketplaces and technologies facilitating virtually enhanced ecommerce. If it improves conversion rates and creates unfair advantages, it is valuable — if it can be applied across a range of businesses it is exponentially so.

But AR and VR are not the only types virtual experiential commerce. Brit Morin of Brit + Co is creating a lasting brand by baking real world experiences right into the product.

What started as a DIY hobbyist site now sell video classes on a wide range of hobbyist activities like knitting, scrapbooking, handicrafting and more — and they make great money from that. It gets better though.

Source: Brit + Co

Brit + Co sells kits too. Want to take our course on sewing? Here is everything you need (at a nice, high margin price point). They built a brand around creative empowerment, started charging for courses and added a significant ecommerce element.

That is a defensible business. That is a company killing it with virtual experiences and content driving real world sales.

Futuristic types of virtual commerce

Virtual world commerce

Freemium is an increasingly popular model for games. Play your favorite MMOG, FPS or RPG game with friends and of course you want bonuses — better armor, more lives, bling… for one reason or another, people PAY for virtual goods.

Expect this trend to continue. If and when virtual reality becomes ubiquitous, more and more commerce will occur with virtual goods.

In minecraft people build worlds. They spend hundreds of hours perfecting them. Those same individuals (and many more) will want to perfect their virtual experiences — the right sofa, new nikes, an anti-gravity machine… the opportunities are endless.

Source: VRFocus

If and when people begin spending more and more time in VR, expect the economies to boom. It will be a goldrush and very likely a blackmarket to begin with. The entire structure of “society” and “commerce” will need to be rebuilt and redefined.

What are the rules in VR? Is stealing wrong?

And what about the world’s oldest profession? Surely prostitution, though not typically considered ecommerce, would enter into this realm. In a virtual world, who is harmed?

Look at the porn industry. As vile as it may be, they are some of the earliest innovators and adopters of new technologies. I’d argue porn will likely lead the way on pushing VR.

According to The Huffington Post, about 30% of the data transferred across the internet is porn. And in a new world with new rules, who sets the laws? Who enforces them? Virtual prostitution will drive much of the commerce engines and business models of VR. It will create frameworks and opportunities for other service providers to begin offering and monetizing their skills.

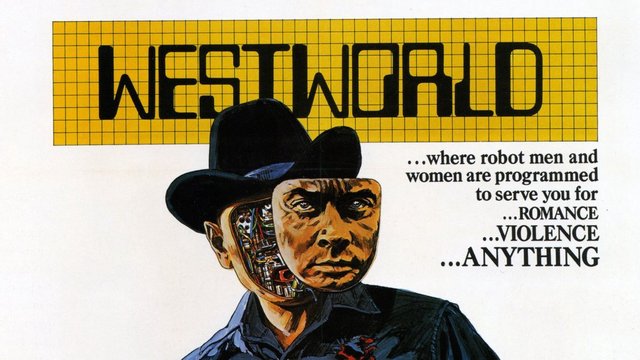

And all this is incredibly controversial. Are we in West World yet?

Source: MikesMovieCave

And what about 3D printing?

Where do virtual assets you create in the real world land? Will patents on 3D printed designs become mainstream?

Either way society is looking at some shifts. If 3D printing technology FINALLY gets towards what has been overpromised for years, the world’s supply chains would break.

What purpose would manufacturing in China have if I can print an iPhone at home? Surely human workers will be outpaced by machines. When these machines become small enough and ubiquitous enough, the majority of sea shipments would cease to exist.

But that is betting on a future that 3D printing has failed to deliver to date. Either way, lets forecast the future. Who wins here?

Not manufacturers. Not 3D printer makers either.

3D printing makes supply chains flat. That means vertical integration opposes their very nature. So real money won’t be made by the makers… anyone can do that. And that drives competition in a race to the bottom.

To win the game, you need to own the platform, the marketplace or the IP.

Android is a good metaphor for the platform play. You own the operating system, aggregate data and can advertise or upsell as you see fit.

For marketplaces, think Amazon. People don’t want to go to a million torrent sites to find the designs, they want fast and easy. A marketplace connecting printers with IP creates value for both parties and a simple commission structure for the marketplace (aggregator of supply and demand)

And of course IP. Patent trolls make money. But so do product creators. Consider 3D intellectual property like an ebook — create it once and continuously sell. Owning the IP is the least scalable of these models but a great option for DIYers and early adopters looking to own a piece of the pie.

What do you think?

Lets face it, I don’t have a crystal ball. The world evolves on its own and we can never really predict the future. But we can guess…

So what do you guess? What are your thoughts on the article, the future of ecommerce and the implications for society as a whole?

As always love to debate and hear other smart people’s perspectives.

Learned something? Click the share buttons on the side to say “thanks!” and help others find this article.

Originally posted on Medium

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://thinkgrowth.org/the-broken-business-of-ecommerce-and-why-porn-and-prostitution-can-fix-it-6aac8cfa51dd

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit