In order to ensure that its citizens have access to basic resources and services (i.e. healthcare, infrastructure, etc.), a country needs either enough natural resources within its borders to match its ecological footprint or enough money to address these needs through international trade. When neither of these two conditions are met, the country may end up in an ecological poverty trap. According to a new study, the vast majority of the world’s population live in such countries with both natural resource deficits and below world-average income.

A poverty trap is created when an economic system requires a relatively significant amount of capital in order to earn enough to escape poverty. Due to its spiraling mechanism, it forces people to remain poor.

But poverty can be used to describe a much broader scarcity than just lack of monetary capital. In their new study, researchers affiliated with the Global Footprint Network, a research organization that aims to change how the world manages its natural resources and responds to climate change, introduce the concept of an ‘ecological poverty trap.

The term describes both the lack of economic capital and the lack of natural resources, most notably biological ones, relative to a population’s needs.

In 2020, the global demand for biological resources exceeded the amount Earth’s ecosystems produce by at least 56%. Some examples include deforestation at a higher rate than forest growth, groundwater depletion at a higher rate than it can regenerate, and overfishing.

In other words, in order to sustain our lifestyles, we would need at least one and a half Earths. So, clearly, we’re currently massively overshooting the planet’s natural resources.

Mathis Wackernagel, the President of Global Footprint Network, and colleagues analyzed the ecological deficit — the amount of biological resources a country consumes in excess of what their ecosystems can renew — of various countries between 1980 and 2017.

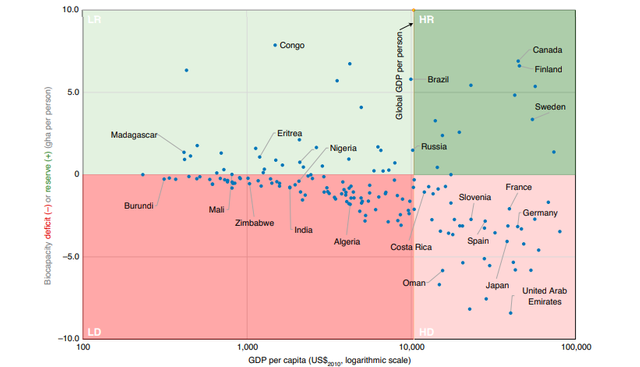

The researchers classified countries in four categories based on this ecological deficit, as well as their gross domestic product (GDP).

In 1980, about 57% of the world’s population lived in a country experiencing an ecological deficit and below world-average income. This figure surged to 72% in 2017.

The researchers also found high- and low-income countries with an ecological deficit used 3.7 and 1.3 times more biological resources per capita than available per person worldwide on average in 2017, respectively.

“Famines and resources constraints have occurred in recent human history. It has been argued that they were caused mostly by unequal access rather than absolute, physical scarcities. However, the emergence of the Anthropocene may have shifted this dynamic. The Anthropocene is marked by unprecedented global change leading to declining global ecosystem health and rising pollution, consistent with global ecological overshoot. Biocapacity constraints, while previously local and distributional in nature, are now emerging on a global scale,” the authors warned in the journal Nature Sustainability.

In order to lessen the burden of ecological depletion, the authors have proposed policies that enhance countries’ resource security by managing both resource demand and resource availability. Some of the proposed solutions involve conserving and restoring biodiversity and ecosystem health, making cities more efficient in terms of energy use and transportation, improving food-related footprint by deemphasizing animal-based products and avoiding food waste, and encouraging smaller families so as to lower the rate of population growth.