This quote is ironic because Rothbard is an individual who exemplifies economic ignorance coupled with a vociferous opinion on the subject. I almost hate to attack Rothbard since I actually do enjoy reading his works, but I feel obligated to point out the economic blunders of the Austrian School.

Origin of Money

The Austrian School, along with most other "classical" schools of economics, gets just about everything wrong about money. The classical narrative goes that primitive societies used barter, but found exchange to be difficult in scenarios where the two parties to a trade were not in need of the other’s product. Consequently, they had to find some commodity that both individuals were willing to accept as payment and use this commodity as a medium of exchange, and this commodity (e.g. gold) is what we call money. Gold was too cumbersome to carry around, so people started storing their gold in warehouses (banks) and they began trading the warehouse receipts as money (cash). “Fiat” money or credit/debt-based currency came about when the State decided to eliminate the gold and circulate the receipts only.

This narrative makes a lot of sense and sounds pretty good. The only problem is that it is historically false. Systems of credit and debt (what Austrians would call “fiat money”) actually preceded the development of so-called “commodity money.” Credit/debt systems trace back to at least the 21st century BCE. Monetary systems developed out of them, precisely the reverse of the Austrian narrative. And the origin of money was tangled up with slavery, debt peonage, and primitive States of all things. IOUs and other forms of “fiat” currency are attested to in the archaeological records way before commodity money is. And the use of cattle or chattel as a unit of accounting served almost as a quasi-fiat money long before commodity-money came about. Cattle and people weren't used to purchase things, but rather as a unit of measurement—other things were valued in terms of cattle/chattel. Furthermore, barter actually only occurs as the norm within societies where the monetary system has collapsed. So the relation between commodity money and barter is the reverse of what the Austrians claim.

If you spend much time researching libertarianism, you’ve probably seen the above symbol before. This is cuneiform for “freedom.” Right-libertarians have appropriated the symbol for various purposes. What most of them do not know is that this symbol originally meant “remission of debt.” It was basically a paid-in-full stamp. In ancient times, people could be taken as slaves for debts. And this symbol for freedom referred to the release of such slaves and their restoration to their original status in society.

Money had a tendency to develop in various different and complex ways. Sometimes it developed from systems of debt and debt-peonage, sometimes it developed from units of accounting, but it almost always required the sanction of the State to become standardized. Market economies are the product of government intervention. When a State issues a currency and demands taxes that can only be paid in the State-sponsored currency, it creates an artificial demand for the State-sponsored money. Everyone ends up needing the State-sponsored currency to pay their taxes, so they end up having to hoard it and ultimately it acquires an artificial value and people begin to trade it as a commodity, which leads to the development of markets.

In short, Carl Menger’s work On the Origin of Money is totally false. The Austrian School got it all wrong on the origin of money. Consequently, Murray Rothbard’s The Case Against the Fed is totally off base because it is predicated on the premises laid down by Menger, all of which were incorrect. (More on this to come.)

(Cf. David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years; Alfred Mitchell-Innes’ What is Money? and The Credit Theory of Money, Georg Friedrich Knapp’s The State Theory of Money; also check out Modern Monetary Theory or MMT, the area of macroeconomics that focuses most on these topics.)

The Quantity Theory of Money

The Austrian School adheres to the defunct quantity theory of money, which holds that changes in prices are always directly correlated to changes in the money supply. In A Tract on Monetary Reform, John Maynard Keynes thoroughly refuted the quantity theory of money. The general thesis of Keynes’ book was that both inflation and deflation are inherently bad, as they both have “an effect in altering the distribution of wealth between different classes…. Each has also an effect in overstimulating or retarding the production of wealth…”(A Tract on Monetary Reform, Ch. 1) Keynes contends that a monetary system ought to be designed in a way that stabilizes the price level and prevents fluctuations in the value of the currency.

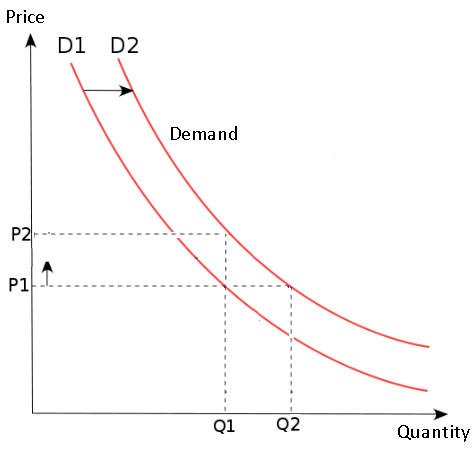

What the Austrians fail to realize is that the value of a currency is determined by supply and demand. If there is an increase in foreign demand for U.S. dollars, then there will be an increase in the value of U.S. dollars. If there is a decrease in demand for U.S. dollars, then there will be a decrease in the value of U.S. dollars. So, a devaluation of currency can occur without any change in the money supply. There is no necessary direct correlation between price inflation and monetary inflation. If you want to stabilize the value of a currency in order to stabilize an economy, it will be necessary to adjust the supply in response to shifts in demand.

To the Austrian, this may seem ridiculous. Please bear with me. It’s really quite simple. Think about supply and demand in general. Take any commodity and you will find that there are people in the marketplace trying to acquire it, on the one hand, but that there is also a manufacturer/producer, on the other. The producer produces the supply and demand is left up to the consumer. If the producer’s role as the regulator of supply were to be removed from the equation, and the supply were to be fixed, the market for the commodity would eventually collapse. The same goes for money. The banks that issue money are the producers. And it is their job to regulate the supply. If they were to ever stop regulating the supply, the market would stop functioning.

A major failure of the Austrian School is its failure to recognize that both supply and demand are determining factors in price formation for all commodities, from widgets to money itself. Although the Austrians recognize this as a general rule, they fail to apply it to monetary theory.

The Virtues of Gold

As a consequence of their adherence to the quantity theory of money, Austrians have typically advocated a return to the gold standard. Although this has changed somewhat since the Bitcoin revolution, Austrian theorists such as Murray Rothbard (The Case for a 100 Percent Gold Dollar) and Ron Paul (The Case for Gold) have advocated not just a return to the gold standard, but for a pure gold standard with a completely unregulated currency. Although Rothbard and Paul would both like to see competing currencies, they hold that a completely unregulated currency based in gold would be the best type of money imaginable. If you simply peg the dollar to gold and don’t regulate the supply, the value will stay stable.

This is simply nonsense. If the U.S. were to adopt a pure gold standard today, the value of the money would fluctuate drastically as a result of foreign trade. Every time the U.S. bought foreign goods, gold would leave the U.S. money supply and deflation would occur. Every time another country bought American goods, the U.S. dollar would decrease in value as the American money supply was inflated by the inflow of gold. A pure gold standard would be a volatile monetary system with drastic fluctuations. It would be highly unstable. The reason the gold standard has been rejected by every country in the world today is because of the rise of the global economy. As international trade grew, the instability of domestic price levels grew.

Inflation is Bad/Deflation is Good

Following from the erroneous views previously mentioned is the Austrian School's general belief that inflation is always bad and deflation is always good. As Keynes’ noted, both inflation and deflation signify a redistribution of wealth out of the hands of one class and into the hands of another class. Deflation transfers real wealth from those who are holding assets and gives it to those who are holding cash. Inflation can indicate that the currency is being devalued by the State, but it can also indicate economic growth. Deflation can indicate a strong dollar, but it can also indicate a recession. If the economy starts to fall apart and banks start going under, the deposits in those banks can fade into nonexistence, causing a contraction of the money supply (monetary deflation) and a corresponding increase of the value of each unit of currency (price deflation). Nevertheless, the economy will be in a depression as there will be too few dollars available for consumers to buy up supply; and the scarcity of money will not allow the market to equilibrate—supply and demand will be stuck in a state of disequilibrium. Although the Austrians were partially right in their analysis of the business cycle, they failed to realize that deflation was a major factor in creating and dragging out the Great Depression.

Competing Currencies as a Solution

Austrian theorists hold that government money is bad and that competing currencies should be allowed. They believe that competition in this field would put the government out of the money business. However, assuming that government money really is bad, Gresham’s Law indicates that all the good competing currencies would fail and the bad money would prevail.

Suppose that there are two currencies on the market. One has a high value (i.e. is “good money”) and the other has a low value (i.e. is “bad money”). People will have a tendency to hoard the good money and spend the bad money. People will hold on to the money with higher value and exchange the money with lower value. Ultimately, the bad money will continue to circulate as a medium of exchange and the good money will be hoarded as an investment instead of circulating as a medium of exchange.

This can be witnessed with Bitcoin. Bitcoin has a high value relative to the dollar. It is “good money.” Yet it is precisely because it is good money that it tends to not be used as money at all. A great many people who own Bitcoin hoard it as an investment rather than spend it as a currency. I suppose that the Austrian could throw Thiers' Law at me in rebuttal, but I would point out that good money only drives out bad money when the bad money is completely worthless. Good money only outcompetes bad money when bad money is sufficiently bad. In a system of competing currencies, the good money would only outcompete the totally bad money, while the moderately bad moneys would outcompete the good money. And, I would argue, that the government money would often be the moderately bad money that drives out good money.

Fractional-Reserve Banking

The Austrian School rails against fractional-reserve banking. Their dislike of fractional-reserve banking is a side-effect of their failure to understand what money is. They hold that money originated as a commodity (e.g. gold) that was used as a medium of exchange. The gold was then stored in warehouses and warehouse receipts were issued. And the warehouse receipts became cash. When the bank gives out loans, it is issuing warehouse receipts for gold that it does not actually have. Fractional-reserve banking, upon this narrative, originated as a kind of ruse.

As I mentioned above, this narrative is false. Money in the form of IOUs or credit tokens preceded commodity money. Money (at least, money as we know it) originated as IOUs issued by the State. The State issued these IOUs or credit tokens and demanded them back in the form of taxation. The taxation established a demand for the tokens, since everyone had to have them to pay their taxes. This standardized the currency and allowed for a market to take root. Some States started using metallic coins as their currency, which turned out to be a good idea since foreigners would accept the money just as easily as citizens would. Why? Because they could melt the money down and use the metal to make jewelry and such. The money had an intrinsic value, which gave it a sort of superiority over totally fiat currencies.

Since the money isn’t a commodity on store but an IOU, the issuing of another unit of currency is not a fraudulent receipt for a nonexistent commodity but rather another IOU in addition to those already on deposit. There is no necessary ruse or theft involved in fractional-reserve banking. (There are plenty of ruses taking place in the banking industry, but fractional-reserve banking isn't one of them. Interest, perhaps, is such a ruse.)

Rejection of Evidence: Quantitative Easing and Minimum Wage

The Austrian School bases its entire dogma on theoretical analyses and philosophical speculation. It rejects objective evidence and does not look at market research. Thus, Austrian Economics is an ideology rather than a science. There are two obvious instances where the Austrians have refused to take evidence against their theory into consideration. The first is the fact that the Fed has inflated the money supply drastically but the value of the currency has not dropped in proportion thereto. The second is the fact that minimum wage increases do not result in higher unemployment as Austrian theory predicts.

Following the 2008 recession, the Federal Reserve resorted to Quantitative Easing (QE) in an attempt to fix the broken economy. According to Austrian theory, an inflationary policy to the tune of 85 billion dollars per month (as per Fed policy in 2013) would have quickly led to high inflation or even hyperinflation. Nevertheless, the Fed’s “inflationary policies” didn’t cause much price inflation at all. This is direct evidence that demonstrates that there is no direct correlation between changes in the money supply (monetary inflation) and changes in the value of money (price inflation). Yet, the Austrian School still refuses to revise their position on the quantity theory of money. Changes in the value of a unit of currency can either be driven by supply or they can be driven by demand. If a change occurs in demand, then it would be necessary to adjust the supply accordingly.

Furthermore, Austrians hold that an increase in the minimum wage will always result in an increase in unemployment. If the cost of employing people increases, the employer will employ fewer people. This is another Austrian dogma that is theoretically sound and philosophically tenable. However, it does not correspond with reality. There have been a number of minimum wage increases throughout American history, yet there is no statistical correlation to indicate that more unemployment resulted from the minimum wage increases. In fact, the statistical correlation tends to be the opposite. Instead of increased unemployment, minimum wage increases tend to result in a shrinking of the wage gap between the lowest paid employee and the highest paid employee. In order to compensate for the increase in the minimum wage, a corporation can simply reduce the amount that it overpays its executives. Instead of a spike in unemployment following increases in the minimum wage, we have consistently seen a shrinking of the wage gap between employees at the bottom and employees at the top. There is all kinds of market research to back this up. There are tons of studies on the subject. Nevertheless, the Austrian School clings to its defunct theory and refuses to yield to scientific evidence.

Monopoly Theory

Rothbard’s greatest unique contribution is his monopoly theory. Rothbard held that monopoly is impossible under free-market conditions and that all monopolies are the result of government meddling.

This is basically a logical deduction from the premises of individualist anarchism. In State Socialism and Anarchism: How Far They Agree, and Wherein They Differ, Benjamin Tucker points out four main monopolies: the money monopoly, the land monopoly, the tariff monopoly, and the patent monopoly. Tucker makes the case that each of these big four monopolies is enforced by the State. From this it can be deduced that all of these forms of monopoly are predicated on the State’s monopoly on law and security. And so the abolition of this primary monopoly will automatically lead to the decline of the other monopolies. Thus, Tucker follows Gustave de Molinari in advocating competing security forces (or competitive private police).

Rothbard and the anarcho-capitalists have developed this line of reasoning even further, arguing for a free market in law and in law-enforcement. Thus, the anarcho-capitalist ends up advocating the privatization of the State. If we abolish the monopoly on governance, then all other monopolies will wither away. Rothbard goes further than Tucker and asserts that all monopolies are State-sponsored and that no monopoly could ever arise in a free market because monopolies are inefficient. More efficient competitors would arise to compete with the monopoly because there would be no coercive apparatus to prevent competitors from entering the market. Monopolies simply couldn't arise and survive under free-market conditions.

The problem with Rothbard's monopoly theory is that it is an over-generalization. It is more of an assumption than anything else. Yes, the most egregious monopolies tend to be State-sponsored, but this does not eliminate the possibility of natural monopolies. A monopoly could theoretically arise under free-market conditions. Allow me to give a few illustrations to demonstrate that free markets aren't necessarily immune to the rise of monopolies.

Imagine that one family keeps buying up more and more land in a certain area. Each generation adds more land to the inheritance of the next. It is conceivable that one could acquire a large territory of land this way. They can then hold a monopoly on land in this territory and charge everyone that wishes to live there rent. And, since it is their legitimate property, they can make up arbitrary rules. The rent is nothing more than a tax and the rules nothing but laws. The free market could lead to a form of monopoly that is virtually indistinguishable from the State. In fact, some anarcho-capitalist theorists have developed this line of reasoning into a sort of defense of monarchy. (Cf. Hans-Hermann Hoppe) Logically, the Rothbardian can't have an objection to a State that is based on "legitimate" property rights.

Let's imagine a town with free competition among electric companies. The cutthroat competition of the marketplace will put most competitors out of business. The few that remain will either combine to form a monopoly or conspire to form a cartel. The three remaining electric companies will realize that competition must logically force prices down towards the cost of production and eliminate most of their profits. Consequently, they will get together and make a pact to not compete with one another. Instead, they will all voluntarily set their prices well above cost of production. They will form a cartel which is functionally isomorphic to a monopoly. Alternatively, they can continue to compete ruthlessly, each undercutting the others’ prices until all the competitors are out of business and only the one company remains. Competition will lead either to a monopoly or to a cartel, both of which are the same thing from the perspective of the consumer.

Imagine a large corporate store opening in a small town. The corporate store is owned by a large national corporation. It has the obvious economies of scale to its advantage. It has a large capital stock available. It can easily afford to temporarily sell its products below cost in order to undercut the prices of the competition. By selling below cost for a year or so, and using its profits from its other stores in order to subsidize and carry the new store, the corporate store can outcompete all the other local stores and put them out of business. The large corporate store could then enjoy a monopoly status. Competitors wouldn't be able to start up and compete because the monopoly has the advantages of size and accumulated capital which will allow it to crush and outcompete any would-be competitor.

The problem with Rothbard's monopoly theory is that there are good theoretical reasons to suppose that monopolies can actually arise under free-market conditions; and there is not a shred of evidence to suggest that monopolies wouldn't arise naturally in the absence of government intervention. Austrian economics is a pro-market and anti-State ideology, and Rothbard's monopoly theory is more of an ideological assumption than a scientific hypothesis.

Conclusion

While Austrian economics is interesting and challenges one to think, it isn't actually economic science. Instead, it is a political ideology masquerading as science, much like Marxism. There certainly are some good ideas within the Austrian School, but it is flawed and blinded by ideological presuppositions and confirmation bias. This does not mean that you should neglect to read the Austrians. You ought to read Rothbard, and you ought to read Marx, but approach their ideologies from a critical rationalist perspective and recognize the good points without getting caught up in the dogmas and cult-like mentality that is so often associated with these ideologies.

I agree that the so-called regression theory is historically incorrect. One could say that anthropologists sometimes (often?) know more about the origins of money than economists. The theories of the Austrian School do seem to have a kind of intellectual sex-appeal. Even Satoshi Nakamoto, the creator of Bitcoin, writes at some length about the regression theory as though it was an established fact. Btw, if you liked this article, you may enjoy reading http://www.newmoneyhub.com/www/money/index.html

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Interesting article, but I believe you have misapplied Gresham's law in your discussion of fiat currency versus bitcoin/altcoins. Truthfully, I had never read Gresham's law until today, but at least under wikipedia's description of this law, it's application is limited to the case of "both "good" and "bad" money (both forms required to be accepted at equal value under legal tender law)". The law as you originally described it made no sense to me, but it makes perfect sense to me under the condition that both forms are required to be accepted at equal value under legal tender law. But, this condition doesn't apply to Bicoin vs fiat currency, so I think your argument on this point is invalid.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit