[Originally published in the Front Range Voluntaryist, article by Mike Morris]

Prior to considerable elaboration by what would come to be known as the Austrian school, [1] economics had not quite yet been considered a specialized discipline. For the longest time it was referred to as political economy, originating from a more general moral philosophy. Economics, if anything, was just more of a sub-branch of this moral philosophy, having little to say on its own.

While predecessors helped to ultimately lead to what is known as economics today (e.g. the classical economists), their work had shortcomings, and a full body of knowledge had not yet totally came into being. Market phenomena wasn’t thought to be a study which could stand on its own, with laws or inner workings that could explain things.

In short, economics is involving conscious actors using scarce means that have alternate uses in the pursuit of subjectively valued ends. Ludwig von Mises narrows down the subject matter, making it clear that the point of concern for economics is the actions of the humans involved: choices, costs, alternatives, preferences, values, ends and means, buying and selling, etc. The human element cannot be removed, as arguably “economists” as John Maynard Keynes have done, as humans, i.e., conscious and purposeful actors, and not rocks, are the subject of study.

Philosophers over the centuries had done much work in ethics, and advancements in the physical sciences had occurred, but they hadn’t narrowed down a study of economics that deals with the actions of human individuals who aim at ends or goals, using scarce means to fulfill them. The classical economist’s acceptance of the labor theory of value, [2] which was adopted by Karl Marx much to the detriment of everything that followed in communist theory, [3] had perhaps restrained them in expanding upon market phenomena.

There remained insufficiencies in the study. How could one properly explain prices, wages, or diminishing satisfaction upon increased consumption, and therefore the law of demand, and so forth, without the marginal concept of utility and other additional economic concepts? More work was needed.

While they might be said to have been lacking in ways, however, what they [the classicals] built helped us reach where we made it today. [4]

“The transformation of thought which

the classical economists had initiated

was brought to its consummation only

by modern subjectivist economics, which

converted the theory of general market

prices into a general theory of human

choice.” (p. 3)

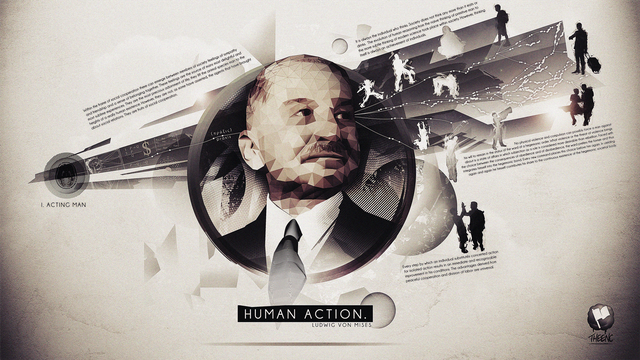

Mises thus sees economics as a distinct discipline on its own. It isn’t just means of explaining prices; economics must be a logical system of the full implications of human action. “Economics opened to human science a domain previously inaccessible and never thought of.” (p. 1) There were things that could be said about human action which could be, beginning with axioms, logically described in sequence for what must follow. That is, the theory, or law, of demand could be traced back to the formal fact that man acts. Thus the title of Mises’s magnum opus is fitting. This—Human Action—is the starting point, so to speak, of economic reasoning.

Even today, unfortunately, economics isn’t considered a genuine, specialized discipline. It is something more of a collection of ideas, not yet integrated into a meaningful and systematic whole. There are no laws or principles, but only theories which are subject to being disproven at any time by new empirical data. Rather than building theory logically, data is thought to be necessary in informing theory. There are no aprioristic truths, such as that “man may not have his cake and eat it too,” a proposition which need not be investigated to be proven true. Economics must imitate the physical sciences where all inquiry is assumed to be an empirical matter, rather than to logically think such ideas through. While economics may have something to say, there aren’t laws; only a collection of theories that may or may not be true, or which await confirmation.

Social democrats are therefore able to dismiss economic science all together, as have the Marxists who believe it to be a “bourgeois concept,” or the Keynesians who have called it a “dismal science” as if to make it seem boring and uninteresting. They’re able to enact a law, which must be backed by violence, to decide later on if it works or not, whereas a science of economics could lend them this knowledge beforehand, say, that wage controls cannot work to produce the said effect of raising wages.

This is all to continue in their ignorance that they can plan the world and that to design a society is only limited by having the right people in power, not due to real forces which would make it unworkable. They are comfortable in believing this, and any economist who demonstrates their limitations is just an annoyance to be ignored.

Economic truths, then, have come to be seen as cold, and therefore not heeded at our own peril. The socialist idea is dreaming beyond the constraints of economic law to promise an essential utopia. It pains them to hear that government doesn’t have a magic prosperity generator, but indeed must harm the process of wealth creation should they try to legislate such a future. They ignored any economic reasoning because “they did not search for the laws of social cooperation because they thought that man could organize society as he pleased.” (p. 2) Society and prosperity could be designed, they believe.

F. A. Hayek, a disciple of Mises counting among the early 20th century Austrians, carrying Mises’s own theories on to receive the Nobel Prize in economics in 1974, [5] stated pertinently that

“the curious task of economics is to

demonstrate to men how little they

really know about what they imagine

they can design.” (The Fatal Conceit 1988)

Still today, the socialists see nothing in their path except getting the right men in power and passing the right legislative acts. It only requires enough activism, or picketing, and so forth, they suppose, until enough people will believe socialism into workability. We’re just one more regulation away from eradicating poverty, I suppose.

For them there is no body of economic knowledge that could explain why they couldn’t achieve their promises of higher wages, more wealth, and free access to everything for everyone. There is no such cause-effect relationship between, say, an increase in the supply of money (inflation) and a subsequent decrease in its purchasing power (by raising prices), or of enacting a law that says “you must pay all employees $X if you hire them” and unemployment. These are to be ignored as fictitious roadblocks in the path to central planning.

So rather, they turn away from the real solution that a libertarian—capitalist—social order can offer, where free markets can deliver all the things we need, perhaps because preconceived notions and internal bias has kept them from discovering anything that challenges what they deeply wish to keep believing.

Enter economics

This importance of keeping good ideas alive is partly the entirety of the tone of Mises’s introduction, in which he wishes to invigorate the study and call forth a new generation inspired by its ideas to take up the task, perhaps after the Keynesian Revolution had swept most of the profession at the time, and bad ideas in mainstream economic circles still dominate today (e.g. Krugman, Stiglitz, Bernake).

There is no doubt before reading further that this is what Mises sees as his goal: to generate intellectual excitement, particularly among the youth, in the issues of economics. The implications of foregoing these lessons—of a weakened fight for liberty—will leave the future of the world less certain.

Mises thus identifies this as the importance of economics: the need to explain why there can be no policies implemented by a State on behalf of “society” or “the nation” of positive benefit, as the actors within are unique individuals who will suffer real consequences from doing so. [6] Economically speaking, a loss in social utility will result from such a policy, as a maximization of utility occurs only in a free market where exchange is free, voluntary, and mutually beneficial. [7] Coerced exchange, such as that of taxation, must necessarily have an injured party, and therefore the opposite effect.

Politically, as Mises is known to have pointed out, since there’s no going back once interventionism is initiated, i.e., inflationism leads to rising prices leads to calls for price controls, tyranny may be had in the name of abstractions such as “the common good” should people refuse the lessons of individualist economics. The individual is primary in the Misesian analysis, as it is he who acts, values, makes choices, etc.

To be scientific, though a branch of philosophy and necessarily directly related with ethics, economics would have to purge itself of ideology and value-judgements as a strict science of human action in order to develop a system without political bias. At least it must qua economics [8]. Up front here, then, Mises instantly points out his adherence to methodological individualism. [9] It is improper and unscientific to start by viewing groups and suppose that groups act towards ends. Groups are composed of individuals, and only the individual acts. [10]

Are the youth getting it?

The concept of science, what should be understood as correct knowledge, is popular on colleges today. Students march in its name and hold scientific truth highly. But it is necessarily the physical or natural sciences (physics, chemistry) which might occupy a place of importance. Concern is that the globe is warming, and deniers of the need for state-intervention to remedy this are the ones not on the side of science, the virtuous banner they stand behind.

But what they might be ignoring is economic science (science, because there is a body of true economic statements), refusing to give it any attention as is done in the physical sciences, which have always been seen as much more prestigious than a social science that had not invented new machinery or tools which have bettered our lives. Many of them might consider that “the proof is in,” too, and without economics that might turn them against taking state intervention for granted, anyone therefore against the data—and the need to act collectively to combat it—is undeniably wrong.

For Mises, however, economics is of equal importance and science is never settled; it’s an ongoing process that always needs improvement. A new paradigm could always come along and shake up the older one, perhaps especially so in the physical sciences where falsification is all the more likely. Economics is built up logically, beginning with true axioms and deducing further truths, whereas the methodology of the physical sciences is empirical and requires testing and searching for the causes. These approaches are necessarily the opposite of one another. [11]

That’s why, for economics, Mises points out that this is a failure on their part to see that it was the ideas of good economics, which gave us classical liberalism and a general hands-off approach to the economy, that allowed for a flourishing ultimately giving us the Industrial Revolution. This Revolution wasn’t mere coincidence of the times, but the result of a general American acceptance of the ideas of capitalism, i.e., a private property order absent state economic interventionism.

Economics, however, being founded in logic, is on more solid ground than observations in the physical sciences which are subject to being upset by newer findings. [12] Working through the logic, and beginning from irrefutable premises (i.e., that man acts and to deny this would be a human performing an action), each step along the way provides incontestably true statements as well. If A implies B, and A is true, then B is true too.

But because there are imperfections, or that economics does not adhere to the methodology of the physical sciences, however, does not invalidate that there is a body of knowledge that is created around the specific study of economics, or human action. That is precisely what Mises has set out to perform herein.

Economics is the logic of human action. This is only a sub-branch of the greater praxeology, in which Mises sees economics as the most elaborated. Economics considers that there are individuals who must make choices; that he has alternatives before him; and that he must therefore rank his preferences and find suitable means as to make purposeful action toward those ends he subjectively values. This act of choice, for Mises, that humans act and must act, and that attempting to refute this would constitute a contradiction, is the axiomatic beginning of what we call economics. [13]

Anti-economists

Amazingly, old debates rage today. As we briefly mentioned, there are many detractors from the idea of there being a science of economics, which has laws universal of time and place, that apply to all human action. The Marxists, for one, are of this notion. Mises accuses Marxian thinking then of “polylogism,” meaning that economic reasoning, which might be considered a white man’s thing, isn’t logic that holds for everyone. [14] It was merely invented to justify capitalism, to which Mises is one of its most astute defenders.

“Marxism asserts that a man’s

thinking is determined by his

class affiliation. Every social

class has a logic of its own.” (p. 5)

Historicism, as another detractor from economics, “aimed at replacing it [economic logic] by economic history,” (p. 4) where empiricism stood as the only method that could explain any economic phenomena. Furthermore it [historicism] “asserts that the logical structure of human thought and action is liable to change in the course of historical evolution.” (p. 5) So nothing could be known for sure, and logic is an unreliable method for understanding economic events. There, again, cannot be logical statements such as that an increase in the supply of money must necessary mean a decrease in the purchasing power of the preexisting units of money, [15] or that a price control set below the market-price (a maximum price) must necessarily cause a shortage.

Irrationalism is yet another opponent of economics. This assumes that humans are irrational, and therefore reason is unsuitable for studying humans, and probably an argument for why man cannot be free. This is why rationalism, where reason is our guide, is necessary for our study of the social sciences, as economics cannot be built upon some flimsy view of man.

Since economics can refute the logic of its detractors, “polylogism and irrationalism attack praxeology and economics.” (p. 5) Much like how Keynesianism can hardly be considered economics as much as it is an economic rationale for permanent inflationism and other such government intervention,

“The main motive for the

development of the doctrines

of polylogism, historicism, and

irrationalism was to provide a

justification for disregarding

the teachings of economics.” (p. 6)

Often, rather than refute the economics, they assume it away. [16]

But Mises was undeterred. Despite these attacks, economists should continue their work, never tiring in their efforts to define in clear language the deductions of absolute truths that follow from initial, axiomatically true premises. [17] An obvious motivation behind Mises treatise, then, is that he saw economics must not only be defended against its criticisms, but must be elaborated to stand on its own in a timeless work for the scholarly student of economics. Ignoring the task was unacceptable.

“The system of economic thought

must be built up in such a way that

it is proof against any criticism on

the part of irrationalism, historicism,

panphysicalism, behaviorism, and

all varieties of polylogism.” (p. 7)

How to view economic freedom

The real world is not perfect; it is not certain; the future cannot be known or predicted; people do make bad choices at times; it is not ever in the state of equilibrium. So, nor is economics perfect. But it is still what we’re working with now.

“There is no such thing as perfection

in human knowledge, nor for that

matter in any human achievement.

Omniscience is denied to man.” (p. 7)

If the market economy, then, made up of men, is compared to the benchmark of perfection, the actions of men within this market economy can be said to reveal failures. Perhaps it will always fall short in theory if its soundness is relevant to perfection. [18] So we are to forget about government failures, and make excuses for all these shortcomings found in the free market economy.

“Market failure,” then, it would seem is yet another term used to justify state intervention due to some alleged imperfection. Unlike the actors, who might at times make bad decisions, the State is omniscient and should step in and make the correction. They are the all-knowing men, unlike us mere mortals. So the story goes, anyway.

But since humans admittedly aren’t perfect, it is illogical to assert that a government, made up of humans, can intervene in the market economy for positive results. Would not they be self-interested, too, looking after their own before everyone else? [19] Surely they would be. But worse, the incentive of profit in the market economy is in the act of satisfying consumer preferences. All actions by the State—a non-market entity—mean coercive interference with the market economy, injuring others in the process. Thus, within the State, the incentive is to increase the plunder and secure the continuation thereof, not toward the goal of bettering humanity. Hardly what we might call a benefit.

As Mises concludes, economic science will always need a continuance of work, as well as enthusiastic defenders willing to take up its cause into newer generations. This is surely what Mises hopes for in his writing. “A scientific system is but one station in an endlessly progressing search for knowledge.” This doesn’t mean that economics has nothing to say, however. To the contrary: “..to acknowledge these facts does not mean that present-day economics is backward. It merely means that economics is a living thing—and to live implies both imperfection and change.” (p. 7)

A revolution in thought

Ideas played a part in a liberal episode in history, that, although imperfect, is what gave rise to the great wealth Western countries still experience today; a history which Mises had already then seen as lost and in need of rediscovery. These ideas must always be reconstructed in a way that can inspire the youth to take them up, and supply their arsenal with ample attacks against socialism, quite frankly to assure the survival of humanity. The billions alive on this planet today whom were previously unsupportable are alive because of the relative freedom in economic exchange we have today, despite that it has been severely hampered by government economic policy. Socialism cannot feed men, but is quite literally a doctrine of starvation, and thus must be debunked.

Another set of detractors are the empiricists themselves from the physical sciences, who believe they’re special because economics hasn’t offered the world the things they have. Technology has advanced the world, but economics has not. Mises saw this as a slap in the face to the conditions which made the world ripe for their achievements to ever materialize in the first place. It might also be necessary to point out that, no matter what ideas any society may have, it takes capital investment to complete them, and this requires savings, which further entails a lowering of overall time-preference in that society.

While economics cannot explain everything, for instance how to build upon the technology that is needed to advance civilization, it plays an important role as a social science in logically tearing down the barriers that are inevitably put in place by states that would otherwise restrict their arrival. Mises says,

“It was the ideas of the classical

economists that removed the

checks imposed by age-old laws,

customs, and prejudices upon

technological improvement and

freed the genius of reformers and

innovators from the straitjackets

of the guilds, government tutelage,

and social pressure of various kinds.

It was they that reduced the prestige

of conquerors and expropriators and

demonstrated the social benefits

derived from business activity.” (p. 8)

Those most focused on the physical sciences, then, where everything is reducible to mere mechanics, may be tempted to dismiss the role of creative decision making in bringing about human welfare, and therefore may not realize that economic liberty must precede technological advancement.

“...none of the great modern inventions

would have been put to use if the mentality

of the pre-capitalistic era had not been

thoroughly demolished by the economists.

What is commonly called the ‘Industrial

Revolution’ was an offspring of the

ideological revolution brought about by

the doctrines of economists.” (p. 8)

The Industrial Revolution, while not perfect, was the child of the much larger American Revolution which set forth libertarian principles for how the social order ought to be, and that was freedom from aggression in the form of taxation, regulations, tariffs, and the ideas of self-determination and private property. In a word, capitalism. As Mises says,

“What is wrong with our age is precisely

the widespread ignorance of the role

which these policies of economic freedom

played in the technological evolution of

the last two hundred years.” (p. 9).

These American ideals have long been forgotten about, and as many feared, substituted for the almighty State, its exorbitantly expensive military and wars, and political conflict as the center of life. Unfortunately, with statism as the order of the day, those most likely to uphold America's position as an anomaly in the world for a shot at liberty have succumbed to more fascistic tendencies of economic nationalism and militaristic expansionism. Americans today have lost the values they used to uphold of absolute liberty, and instead have substituted for them perverse ideas as to how man should live, or be left to live.

“The economic policies of the last decades

have been the outcome of a mentality that

scoffs at any variety of sound economic

theory and glorifies the spurious doctrines

of its detractors.” (p. 9)

Today, economics is reduced to nearly nothing in the public schools; much less seen as something significant that everyone should be schooled in (perhaps because this would refute the alleged essentiality of government they attempt to cultivate). If any courses are taken at all, they’ve been diluted by jargon, graphs, and uninteresting stuff that will not spark a fire in someone reading it. Economics is made out to be a something concerning personal finance, mathematics, or business, rather than a body of knowledge which can explain cause and effect in human action. If taxation is discussed at all, the legality or history of its enactment might be covered rather than the relative impoverishment effect. If the Federal Reserve is discussed at all, it isn’t in its origination in a conspiracy by bankers, or how inflationism is the cause of the business cycle, wealth redistribution, or other negative effects upon the economy. Its existence is taken for granted while the lesson following is Fed mechanics, such as how it conducts its “open-market operations,” rather than why this should be done at all.

As Mises correctly saw it, economic ignoramuses are a threat to liberty. Policies against liberty come about precisely due to an ignorance of them. Legislative action nor good intentions can trump economic laws. Mises is adamant here: “The characteristic feature of this age of destructive wars and social disintegration is the revolt against economics.” (p. 9) As we see today, of the Leftist embrace of “socially liberal” ideas such as transgenderism, attacking the family, property, money, prices, profits, wages, etc., social degeneration appears to be coming about. The political-Right, perhaps keen on culture and more disposed to champion economic liberty, has dismissed economic lessons too.

A restoration of good ideas in need

Since actions are led by ideas, and those ideas must be good, workable ones, it’s necessary that a population do not hold economic fallacies. If they do—if they believe creating money can create new wealth rather than to redistribute existing wealth to the inflationists—then they are doomed to repeat failures in history. For instance, socialism is not even good in theory, and leads to horrors (starvation and murder) in practice. Although economic freedom may be hard to obtain, it is actually workable once obtained, unlike socialism. In economics, there are really only good ideas and bad ideas; there’s no such thing as “works in theory but not in reality.” There is no just separation of the two: if it isn’t realizable in practice, it is a bad theory. [20]

We see today, well into the 21st century, that ideas of protectionism are far from dead. The Trump administration campaigned on getting tariffs on imports, to protect American steel and other industries; the Leftists of the Marxist variety still believe that technological advancement (labor-saving devices) causes unemployment (among other dangerous ideas); respectable men in industry call for a “Universal Basic Income” as the eventually needed solution of the robot takeover [21]; scientific research is said to need protection and subsidies by government because it otherwise wouldn’t be profitable, rather than subject everyone to the test of profit and loss which is the only efficient, rational allocation of resources; etc.

Quite literally, then, our “society,” for lack of a better word, is doomed should they repeat the fallacies of the past, and should economics be unable to advance into the minds of the people. What was once common knowledge, that markets should be free, that price fixing doesn’t work and causes shortages or surpluses, that savings is good and necessary to expand production, etc., have faded into the 21st century, over a half-century after Mises wrote with an authority aimed at changing public opinion on economic matters. They have been swept aside, once again in time, by older fallacies resurrected in new aesthetics.

Few Americans, I would venture to guess, could succinctly explain why printing more money has disastrous effects. They’re all the more likely to suggest it as a solution. Keynesianism, for example, has made it fancy to believe governments and central banks, by deficit spending or inflating, play a special role in steering economic actions. Socialism, long refuted in theory and by experience, has come to be popular among the youth again. [22] Marxist theory and discussion is still popular at the country’s universities, whereas libertarian ideas are condemned as bigoted, insensitive, and a prescription for mass economic inequality.

So economic teachings, essential as they are, are ignored by the masses and downplayed by those in power at a time when they’re needed more so than ever. With the insight of Mises, we can see that social disintegration, the politicization of life, etc., that we experience today makes perfect sense to be correlated with a demise of economic understanding by the masses. Bad economic thinking is coupled with the fall of civilization, just as good economic ideas are responsible for its rise. Thus, we see degeneracy today and behavior that has come far from the traditional values in which Westernism was built upon. What is at stake in defending proper economics is survival of Western culture and civilization itself.

We’re witnessing this more so than ever, as the democratic state has fully politicized the populace, giving us people who are crusading for “social justice” but are without a theory of justice in property rights, people who are begging for economic activism on part of the government but which have no idea the effects of even minimum wage laws (unemployment), as well as identity politics being played on both sides of the popularly accepted political spectrum. Seeing such strife and hostility toward one another demonstrates that capitalism offers us civilization, where people cooperate through the social order that arises out of a division of labor, while socialism threatens to roll back our relations with one another. Since we have come far from freedom, accepting in its place a centrally planned order, the cause of the political climate can be directly linked to government. [23]

Socialism’s popularity comes from the seeming shortcut that it offers to prosperity. The followers of these doctrines truly believe we’re but a few legislative acts away from prosperity, and then may the government lift the natural restrictions of scarcity forever, giving us all great abundance. The socialist intellectuals have made the public believe that economic laws may be trumped by the state, and that, really, the laws themselves put forth by economics are not principles at all, but merely spooks that give an ex post rationalization for capitalism.

Moving forward

There is little hope for the future if the rising generations are convinced of the fallacies of old age. Keynesianism, for one, is essentially a resurrection of old Mercantilist fallacies, as Murray N. Rothbard framed it. In order to change the world, as Mises knew, it was imperative the world be offered an economics with systematic treatment, that could aptly explain why interventionist ideas are bound to fail, and that all such policies of government be held up to these insights in order to demonstrate their perversity.

Not only do they adhere to a backward economics, but they dismiss the history that good economics played in giving us the things we have today. To them, there are no examples of free-markets ever improving the lives of millions; everything we have today is because of the State, not in spite of it. This is the dangerous thinking we’re on to today. That the government is not a parasitical taker which earns its income via taxation, but a benevolent giver that we couldn’t do without. These ideas are pure fantasy.

The socialists today are essentially ungrateful, pseudo-intellectuals who take for granted the capital investment before them, which they intend to plunder into oblivion were the last few hurdles presented by liberty-minded people to get out of their way. Were they successful, the capital stock would be entirely depleted, and economic activity would begin to stagnate. [24] We would all return to a subsistence living. Obviously, anyone should be indefinitely more grateful to be born into a world where capital accumulation preceded their existence, rather than to be born into a deserted island to work with only the originary factors of production, land and labor. [25]

For Mises, to explain the reasons behind prosperity which most have taken as a given was yet another task of the economist. To turn the “dismal science” into something stimulating for the interested students, as all life around us is economics. We must learn if the ends we seek (say, socialism) are attainable by the means we’ll use (force), which economics can provide us with this knowledge.

Economics is a science of means, not ends. As with the limited scope of libertarian legal philosophy that condemns aggression, economic science doesn’t tell men how to live their lives; and it doesn’t even assume why he acts. The goal is giving man freedom to that he can choose his own ends without coercive interference from others.

“It is not its [economic’s] task to tell

people what ends they should aim at.

It is a science of the mean to be applied

for the attainment of ends chosen, not,

to be sure, a science of the choosing of

ends. Ultimate decisions, the valuations

and the choosing of ends, are beyond the

scope of any science. Science never tells

a man how he should act; it merely shows

how a man must act if he wants to attain

definite ends.” (p. 10)

The significance of this treatise on economic principles presented by Ludwig von Mises, what is probably the most significant of the 20th century, is that our very survival rests upon exploding the myths of older ages that have resurfaced to haunt us, and, armed with such knowledge of what must follow from intervention into a natural order, a turning of the tides of the statist order that threatens to end mankind’s existence. Today, most unfortunately, we live in a statist paradigm and not a libertarian one. We have yet to win liberty. The only way to work toward this end is a spreading of ideas. Economics in the Misesian tradition is a great place to begin.

[footnotes]

[1] This wasn’t always known as the Austrian school, as,

for instance, Murray Rothbard in his 1962 treatise

Man, Economy, and State didn’t repeatedly use the

term, but believed he was simply elaborating upon

positive economic laws. However, we might trace the

school’s origin with Carl Menger, who led the late

19th century Marginal Revolution by restoring

economics on its proper path, refuting the objective

theory of value of the classical economists and

replacing it with a subjective, or, marginal utility

theory of value; to his student, Eugen Bohm-Bawerk,

who did work on capital theory, interest, and

expanded clearly upon Menger, as well being one of

Karl Marx’s major late 19th century critics; up to

Ludwig von Mises into the turn of the century, who

incorporated money into general price theory, wrote

very early on the cause of business cycles, and refuted

socialism for its inability to calculate; and culminating

with Murray N. Rothbard, who went on to expand

upon Mises’s treatise in his own massive Man,

Economy, and State, among other prolific works.

[2] The labor theory suggests that the value of

something is “intrinsic” or related to the amount of

energy (costs, labor) invested into its production. But

value cannot be determined apart from individual

assessment, and labor for laboring’s sake (say, to make

mudpies) does not guarantee it will satisfy anyone’s

utility. Value is subjective in the minds of individuals.

It is perhaps for this reason too that Mises sees we’re

dealing with conscious human actors that we cannot

use the methodology of the physical sciences (i.e., to

treat men as stones that don’t act) in economics.

[3] While other factors matter (time, etc.), one of these

detriments is to lead the follower of this reasoning to

believe that there exists exploitation in the

employer-employee relationship of labor for wages,

since the labor theory would have them believe the

spread in their wages-paid (in present) and the

price-made for a good (in the future) constitutes them

being ripped off, rather than to see that value is

imputed backward from the consumer good to the

capital goods instead of the other way around

[4] Though in Rothbard’s view, however, classical

economists like Adam Smith had led economics

off-course, ignoring their predecessor’s subjective

theory of value (of the Scholastic tradition throughout

Europe centuries before Smith, in Spain, Italy, France),

in which it took the Austrians to correct.

[5] There is speculation that the Nobel committee did

not want to acknowledge Mises’s massive

contributions to economics, and so gave this to Hayek

after Mises’s death (though perhaps if the economics

prize had been established before others, he would

have won it early on). Moreover, surely Murray N.

Rothbard, a most voluminous writer in the Austrian

tradition, who knew virtually the entire history of

economic thought, will never receive such a

posthumous award for his too-radical conclusion in

political philosophy of stateless.

[6] Mises is a classical liberal, who, while not

abandoning the idea of government completely,

certainly would submit that it should have no role in

economic matters (exchange, prices, money)

whatsoever. For Mises, however, his idea of

government was that it must be voluntary, and that

people always have a right to self-determination.

[7] And this might be important in showing utilitarians,

so they can understand you can arrive at libertarianism

through utilitarian as well as natural rights principles.

The major fallacy of the utilitarian is to assume utility

can be measured cardinally, and thus interpersonal

comparisons can be made.

[8] Mises maintained economics was value-free, i.e.,

explains cause and effect of various forces without

incorporating ethical problems into it. It is not, for

instance, a matter of opinion that maximum price

controls will cause shortages, etc., but nor does

economics say anything about whether a policy of

price controls is good or bad. Value-laden economics

should be purged from the science. Rothbard’s view

was more so that one could remain value-free as an

economist, only so long as they didn’t propose

policies, in which they would then need to defend a

system of ethics, to which Rothbard adhered to

objective ethics. Mises didn’t necessarily stand for

objective ethics, though he did as a citizen advocate

laissez-faire, but thought of economics as strictly

value-free. The problem is that some economists

make ethical pronouncements while contending to be

acting “value free,” which threatens the scientific

status of economics proper. They have taken the State

and its aggressive acts (taxation) for granted in

assuming it may initiate policies. For Rothbard, one

really cannot avoid ethics; and economics is an

insufficient, though needed, justification for the

free-market. To be a free-market economist is to give

moral sanction to the justness of the property titles

being exchanged. While Mises may have dealt more in

the realm of strict economics, Rothbard helped to

systemize it—ethics and economics—all.

[9] And against the charge that Mises, the Jewish man

who escaped Nazism in Europe for America, is a racist

or a fascist, he is clearly opposed to this collectivist

method of viewing group action. For Mises, all men

have a right to self-determination, a right to leave a

political union they saw no benefit in by remaining.

[10] In this sense too, the State is only an idea,

composed of individuals acting as government agents.

[11] But since economics (logic) doesn’t imitate the

physical sciences (though many, if not most, do try to

use this method), it has taken a lesser place among

people reportedly interested in science.

[12] Though this is not proof that economics as a study

isn’t subject to regression. Indeed, at this very point in

time, the mainstream school engages in fallacies long

refuted by Mises. And before Mises, the Austrians of

the early years had attempted to set economics in its

rightful path again, whereas the classical economists

had gone somewhat off course. What is needed, again,

as Mises calls for, is a rightful return to logical,

deductive, aprioristic economics and a subsequent

abandonment of statist ideas toward the economy.

[13] Mises thought this axiom to be aprioristic too, while

his direct descendant, Murray Rothbard, thought it to

be empirical. Either way, though, this insignificance

doesn’t change what is deduced from this premise.

[14] Marxists might argue I’m an anarcho-capitalist due

to my “white privilege”; because I expect to be a

beneficiary of white, patriarchal capitalism; that the

free-market isn’t real; or that we’re apologists for the

rich, capitalist class (despite that such cronyists seek

protectionism precisely through the means of the

State).

[15] This is also why the historian must equip himself

with economic logic too, or else he may be unable to

explain a historical event, such as an episode on rising

prices. He will need to apply the tools of economic

logic in his historical analysis. On this, see: Theory and

History, Ludwig von Mises.

[16] The Keynesian Revolution for example hadn’t swept

Mises aside by refutation, but because he was ignored

into history. Again, economics over time does not

need to imply progression; the world could very well

move toward bad ideas just as it could good ones. And

for Mises this was of prime importance for

constructing this massive treatise, his magnum opus

which gives us an unprecedented elaboration of

economic theory that, over a half a century after its

1949 publication, still holds the keys needed to

defense the free society today

[17] And this clarity is important, for one interested in

economics would be totally lost to pick up the

jargon-ridden obfuscating Keynes as their

introduction to economics.

[18] As such, then, Mises acknowledges that man may

make regrettable actions, but he is always working

toward an alleviation of the uneasiness felt in his

current state of affairs, and ex ante is making the

highest-valued actions to his knowledge at that time.

[19] On this, the great French classical liberal Frederic

Bastiat famously asked in his magnificent essay The

Law, that, “If the natural tendencies of mankind are so

bad that it is not safe to permit people to be free, how is

it that the tendencies of these organizers are always

good? Do not the legislators and their appointed agents

also belong to the human race? Or do they believe that

they themselves are made of a finer clay than the rest of

mankind?” Mises believed the same, saying in

Planning for Freedom that, “If one rejects laissez faire

on account of man's fallibility and moral weakness, one

must for the same reason also reject every kind of

government action.”

[20] And thus seemingly, instead of admitting that they

have a bad theory, Socialists continue to make

workarounds with reality, i.e., are in need of a “New

Socialist Man” to come about to make their ideas

work.

[21] These are Bill Gates of Microsoft, Mark Zuckerberg

of Facebook, Elon Musk of Tesla and SpaceX, and

others like Stephen Hawking.

[22] Bernie Sanders ran a rather popular campaign in

2016 as an explicitly democratic socialist, which is but

a softcore variant of communism, to which Sanders

was likely hiding behind, fooling his supporters.

[23] And this is highly controversial to the people who

assume “taxation is the price we pay for a civilized

society”, and that “without the state, there would be

chaos.”

[24] And this point is interesting enough that socialism

seems to be popular mostly in the Western world,

where there is great wealth already from preceding

capital investment which has enriched the

populations there. The campaigns of democratic

socialists like Bernie Sanders often reference only the

need for so-called “developed countries” to usher in a

new, more fair age of socialism, which is an implicit

admission that socialism cannot develop countries,

i.e., be implemented from the ground up, but relies on

capitalism to function until at least the market is

squashed to the point of nothing left to offer

[25] And surely here they wouldn’t maintain their logic

of justifying “public goods” either for capitalists, that

beneficiaries, i.e., so-called free-riders (people born

into a world of capital accumulation), owe tax-money

for these externalities they enjoy. Presumably this

faulty theory would be abandoned here.