I sometimes think of what future historians will say of us. A single sentence will suffice for modern man: he fornicated and read the papers. After that vigorous definition, the subject will be, if I may say so, exhausted.

-The Fall, Camus

A commodity is someone's property. John Locke investigated property, and his investigation of property reveals what Karl Marx calls the fetishism of commodities. The word fetish has many connotations, and it is characteristic of Marx's literary style to use such a word, without letting the reader know which aspects of the commodity Marx had in mind when he spoke of their "fetishism." One interesting thing about doing this, however, is that Marx prompts us to reveal aspects of the commodity to ourselves.

Property, as Locke conceived of it, is like a commodity in that they are both the fruits of labor. However, Locke seems to have a more mystical conception of labor's contribution to property. While for Marx labor has been scientifically categorized, Locke seems to view labor in what Marx would call a superstitious light.

Locke calls property a right. The owner has this right to property because he uses his labor to take something out of the state of nature. Thus the law of reason makes the deer that Indian's who hath killed it; 'tis allowed to be his goods who hath bestowed his labor upon it, though before it was the common right of everyone. (Of Civil Government, Second Treatise) The reason this property becomes the right of the owner is because it represents a unification of Body and Soul, those much discussed metaphysical objects that Marx would have nothing to do with in Das Kapital. Property for Locke is at the end of a chain which begins in the individual's mind as a thought or act of willing, and ends with a planned transformation of the extended solid substance into an object that the owner can use. Our idea of body is extended solid substance, capable of communicating motion by impulse: and our idea of soul, as immaterial spirit, is of a substance that thinks and has the ability of exciting motion in a body, by willing, or thought. By his will and the process of labor, the worker organizes the extended solid substance in such a way that he can use it. He organizes the outside substance into the substance which constitutes him as an individual. Nothing but consciousness can unite remote existences into the same person: identity of substance will not do it.

There is very little mention made in all of this of the dependence of man upon his fellows. Locke only considers the rights of the individual, as if one only becomes aware of the existence of someone else when he is robbed. In reply to Locke, Marx says that of course if Robinson Crusoe makes a table on his island, that thing is his possession. But if there is no one else on the island, the concept of property is meaningless. According to Marx, Locke is wrong in thinking that man is by nature all free, equal, and independent. One of the basic features of Man is that he is socially dependent on his fellow men.

The commodity conceals this dependence of man upon his fellows. The fetishism concerning these commodities occurs when Man substitutes a thing for his relationship with others - when he endows natural or artificial things with powers that belong only to living humans.

With every fetish there is a ritual or consecration that the object has to undergo, and the commodity is no exception. Marx speaks of the commodity being immersed in labor; this is its baptism. However, just the fact that it is the product of labor does not yet make it a commodity. Marx looks at feudal societies, where there was private ownership but as yet the commodity had not fully developed. Speaking of feudal society, he says: Personal dependence characterizes the social relations of material production as much as it does the other spheres of life dependent on that production. But precisely because relations of personal dependence form the given social foundation, there is no need for labor and its products to assume a fantastic form different from their reality.

As the society progresses, and as the division of labor in the society increases, different spheres of production become more independent of one another, insofar as the workers carry on specific tasks without realizing as much the interdependence of everyone in society. The whole history of the progress of the division of labor in society is fraught with a conflict of interest between different parts of society. First comes a conflict of town versus country, then commercial versus industrial labor, and finally even among workers engaged in the same sphere of production.

Conflict characterizes the commodity society as much as private property does. Division of labor is the inexorable force which creates conflict and private property. Division of labor and private property are identical expressions: in the one the same thing is affirmed with reference to activity as is affirmed in the other with reference to the product of the activity. As private property becomes more important in society, the social relations become more obscured in that society. This makes itself manifest in surplus value.

As we see in Tolstoy (War and Peace), the peasant is dependent on the nobility. But as the armies of Napoleon march across the Russian frontier, we see how independent the peasant really was as well. He had some land he cultivated for his own use, some cows, and made his own clothes. If there was a conflict between him and the nobility, he wouldn't starve.

Now people confront each other as owners of commodities. By "rights" equal, they equally exchange their commodities in the free market. The problem is, during the transition from feudal to commodity society, everyone was disinherited. People were pushed off the land, and rendered property-less. Forced into the free market, they have to sell their only commodity: labor power. No longer does he make his own shoes, or grow his own food. The division of labor has given him a place in the collective labor of society, where he performs a specific, limited function. In this respect, the division of labor acts like a sieve, sifting the individuals like grains of sand. It takes lumps of sand and breaks them up, and levels them out. Some rocks are left behind, too big to fit through the sieve. These are the big owners.

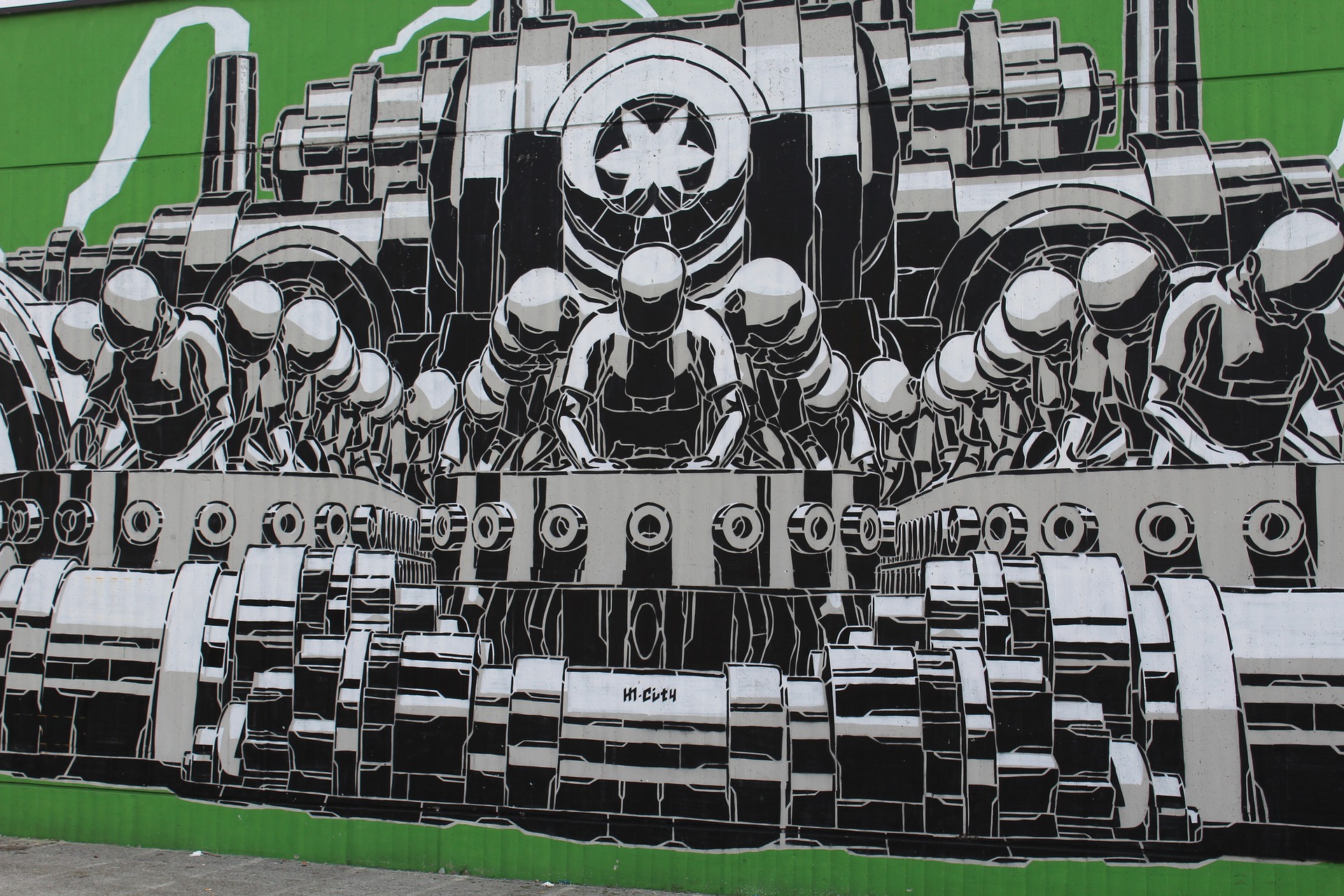

The division of labor plays a unique role in Das Kapital. It creates while destroying, unites while dividing, clarifies while obscuring. The workers are homogenous and interchangeable. Although each is a tiny cog of the total production machine, as they are mere cogs their jobs become interchangeable. Although by "rights" everyone is considered to be equal, this is true until employer and employee walk into the factory. Then the worker walks behind. However, in relation to his fellow workers, each worker realizes the interdependence of all producing jobs.

Marx here is venturing to say that all men are equal, in a way not implied by the equality familiar to commodity society. Marx is saying that everyone can do anything- that as people become adjuncts to the tending of machines, their jobs become interchangeable. Division of labor still exists, but the life of the worker can encompass many different jobs. One day he could farm, and the next clerk in a store.

Although Marx would agree that society moves forward, he would also point out that traces of previous societal relations remain. He even seems to be advocating a reversion back to an earlier state of society. Commodity society is artificial, whereas earlier societies were natural. The most natural of these previous societies was the first - tribal society. Its social organization is patterned after the family. For Marx, the coming society will resemble a large family.

Here the division of labor is spontaneous and clear; society has not crystallized social relationships into material. There is no private property, only community ownership. There is no hypocrisy.

Hypocrisy is what really bothers Marx. It is a theme which is everywhere in Das Kapital. Everywhere the commodity obscures, and hypocrisy arises. He advocates a society without hypocrisy. But what is more modern, more civilized, than hypocrisy? In colonial history, we see the naive primitive conquered by the guile of the sophisticated European. As V. S. Naipaul says in A Bend in the River, But the Europeans could do one thing and say something quite different; and they could act in this way because they had an idea of what they owed to their civilization. It was their great advantage over us. The Europeans wanted gold and slaves, like everybody else; but at the same time they wanted statues put up to themselves as people who had done good things for the slaves.

How deeply Marx wishes to change existing society can be seen. He is saying that what is necessary is a rebuilding of civilization from the bottom up - a sharp and difficult break from the past. But this past is what we also return to. We must become children again, so that we can enter the Kingdom.

These days one can turn oneself into a commodity. A new fashion among newly adult Bangkok "Hi-So" (high society) women seems to be to self modify through what I grew up calling "plastic surgery" to appear like a Barbie doll. Good for the ego, or something, I guess

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Please don't get the idea that I am a communist or that I advocate communism. Far from it. This is meant to be an informative article only!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

And very informative indeed, I don't like when people tags you as communist when you express 1 or 2 ideas that covers the 'we all should have right to...' on paper communism has pretty good things, like universal healthcare/education. I believe the best political path is not following any axis but in between, picking up the things that work from each ideology.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit