One of the most remote areas of the southwest is the region north of where the Colorado river starts to form the Grand Canyon. A couple towns (Kanab, Paige), a somewhat polygamist settlement (Colorado City) and some small villages (Big Water, Fredonia) are about all there is to human settlement in the area, at least until you get to Hurricane/St-George in the north. This area contains the Grand-Staircase Escalante National Monument (from here on referred to as Escalante), a giant federally-protected region encompassing a large amount of very remote wilderness (some of the interior of the monument is still unexplored by foot, and is considered one of the most remote places in the southwest USA).

I have been able to visit this area many times, including this past December while classes were out. Escalante and the surrounding region (south-central Utah) is probably one of my favorite places out of everywhere I've visited (admittedly this is mostly restricted to the west coast of the United States). This post will be an overview of the monument along with my own pictures and experiences there.

This place is an amazing cache of wilderness, geology, fossils, and animal life all in one.

Escalante

Escalante National Monument is a rugged land of canyons, plateaus, mesas, valleys, and mountains. This area is what is known as a high desert - the entire area is above 4000 feet elevation, but gets little rain. The result is a place that is very hot in the summer, very cold in the winter, and remains quite dry year round. Flash floods and the occasional small river are the only water sources here. There are very few trees, and most of the ground cover is small, dry shrubs.

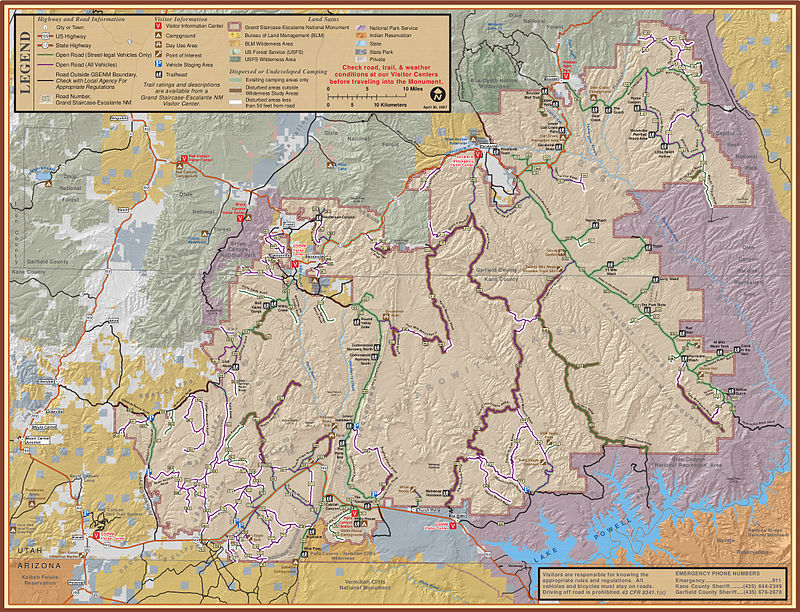

Toadstools on the far southern border of Escalante

Up until recently, the monument took up more land area than several US states (Delaware is the one I see cited the most). The area is roughly bound by Highway 89 to the west, the Colorado River to the east, the Arizona/Utah border to the south, and Bryce Canyon and the towns of Tropic and Canonville to the north (these boundaries are quite rough). Highways go almost all the way around the monument, but very few roads actually make it into the interior. Those that do are somewhat maintained dirt roads that are totally impassable during most winters when it snows/rains. For example, the only "large" road I know of that goes into the monument's interior is Cottonwood Canyon road, which is a one lane dirt road that goes for over 40 miles with no signs of human habitation other than some power lines. This road starts and ends in pretty remote areas too, making the entire area difficult to get to.

Part of Escalante as seen by satellite maps (Credit: Google Maps). The colors are not adjusted.

Numerous plateaus, including the huge Kaiparowitz Plateau, fill the landscape. The Paria river cuts through the center of the monument, leaving enormous slot canyons in its wake, including Buckskin Gulch, the largest slot canyon in the world located just outside the monument. Different colored layers of rock make every part of the monument look different, with elevations varying wildly across the land.

Tropic shale cliffs less than a mile south of the monument, looking north towards the monument

Geology and Fossils: Or, Previous Wildlife

Although I'm not a geologist, I assume that any geologist would love this place. The "Grand-Staircase" part of Escalante's name comes from the numerous exposed layers of different rock.

As you go north through the monument, you cut through higher and higher layers, slightly angled relative to the horizontal. The area becomes even more incredible when you realize what exactly you are walking on.

One of the lower layers in the monument is called the Tropic Shale. This layer is made up of a grey, crumbling dirt that looks uncannily like the surface of the Moon. It shows up in the southern part of Escalante and near the town of Big Water, and can be seen as the thin grey regions on the above satellite map.

Tropic shale plains north of Cottonwood road in the southern part of Escalante

Walk out on the tropic shale and you'll find something strange - small shells litter the ground in parts of the layer. This might make you think that you are walking on a river bed, but there is only one river significant enough to have something as big as an oyster in it - the nearby Paria river, somewhat far from these plains. And on top of this, there aren't any freshwater oysters living in remote Utah desert rivers that I know of. Rather, these shells have been lying there for over 70 million years, untouched until now.

70 million years ago, the area was a vast inland sea, covering much of central North America. Things like mosasaurs and plesiosaurs (quite literally sea monsters) swam in these waters, along with numerous fish and sharks. The oysters and molluscs that lived on the sea floor left their shells behind, which piled up under the mud.

Western Interior Seaway

Credit

Many sunrises and sunsets later, the sea is gone, and a barren desert has replaced it. But the grey tropic shale layer is preserved, and the shells of the sea's inhabitants are still here. I personally found many shells of creatures known as Devil's Toenails (Gryphaea), along with many very large oyster shells. Some areas had so many ancient shells that it was impossible to walk without stepping on them. The layer also contains the bones of fish, sea reptiles like plesiosaurs, and even dinosaurs that washed out to sea before sinking into the mud. Walking out here is strange once you realize that you are walking on the seafloor - in fact, the dirt even resembles a sea floor, being a grey silty material.

Fossils often don't seem "real" - we know that they are old but the age is so vast that you can't relate to it. Standing on a grey plain that looks like a sea floor, with sea shells, that you know was a sea floor 70 million years ago, in the middle of a high-elevation desert, sort of changes that.

Every other layer has its own story and most have their own fossils. For example, just outside the monument I've seen big Navajo sandstone flats made up of fossilized sand-dunes. These dunes are over a hundred million years old and their remains were solidified in place. Again, it's easy to just see these as cool-looking red rocks until you are walking around and come across a big three-toed track stamped into the rock - a remnant of a dinosaur that once walked where you are currently walking. Think about that: 150,000,000 years ago, a huge reptile was walking around and left a track in some soft sandy material. Then you come across it, long after the reptile and all of its kind are gone. Even though I personally didn't see a track (although was apparently really close to a known one at one point), I did see something that definitely looked like an imprint of something, maybe a plant, in the Navajo rock. From what I've read, the dinosaur tracks aren't really that uncommon in that area (obviously not common but not incredibly rare either).

White cliffs in Escalante

Many, many other fossils have been found in or near the monument, including full dinosaur skeletons (and many new previously unknown species!), mosasaurs (large swimming carnivorous reptiles - look them up, I didn't call them sea monsters for nothing), entire petrified trees, and more. And, as much of the monument isn't really accessible on foot, there is of course much, much, much more out there waiting to be discovered.

These beasts, Utahceratops gettyi, roamed the monument years ago, I believe before the Tropic Shale seaway formed.

Credit

Wildlife

Since Escalante is essentially a desert, there isn't quite the diversity of wildlife that, say, a rainforest would have. That doesn't mean that there's nothing here, though!

The ground is covered in small shrubs and grasses. Near areas with water, like the Paria river, larger bushes and even trees can grow, utilizing the additional moisture to grow. There are also a ton of predatory birds in this area, preying on small rodents and rabbits that live on the surface.

While I sadly don't have any pictures, I have personally seen a huge variety of raptors (birds of prey) in and near the monument, including golden eagles, bald eagles, red-tailed hawks, turkey vultures, falcons, and even the extremely rare, endangered California condor. These birds enjoy wide, flat expanses on the tops of the plateaus for hunting, and like to perch on clifftops and the occasional power line pole.

These massive condors, once extinct in the wild, now fly across several areas in the southwest, including the Escalante area. While this is not my image, I have personally seen several condors in this area of southern Utah.

Credit

Larger land mammals include, of course, deer, but also the pronghorn. Perhaps you've heard of "American antelope" - these are actually pronghorns, which are large mammals that look and act a lot like antelope, but are actually more closely related to giraffes. Pronghorn live all over the southwest, but aren't terribly common, and call Escalante home, and this past winter I saw my first ever Pronghorn in the monument.

Pronghorns in southern Escalante! Apparently they also live in a valley an hour east of my university, but I've only been there once and didn't see any.

Pronghorns live on the plains of the southwest and feed on local plants. These cool animals can also run really, really fast: Up to 55 mph / 90 kmph, faster than any other land animal on Earth other than the cheetah cat (Peregrine falcons are faster than both). I personally really like them.

Other animals here include big-horn sheep (in the higher up parts), coyotes, and porcupines. I've heard that there could be bears here, and I know they live in the nearby high elevation mountains, but I'm skeptical if any live in the actual monument.

Looking towards the Paria river (which lies under the jagged ridge) off of one of the best roads in the monument

Threats

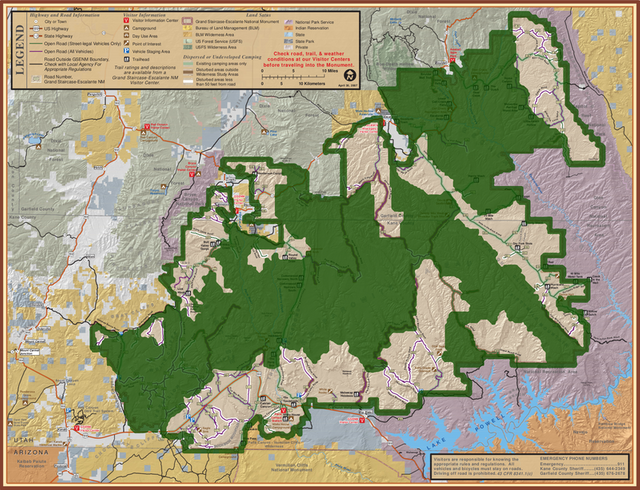

I personally find Escalante to be a really incredible place and I would very much like to keep it that way. Sadly not everyone shares that view. Recently, actions taken by the US president have cut the size of the monument in half, splitting it into two parts. The majority of the pictures I have shown here are no longer within a protected monument (although the toadstools at least are still in a protected wilderness area, which is better than nothing). Unfortunately this removes protections on one of the most unique (in my opinion) places in the country.

Old borders vs new borders

Credit

Allow me a moment to bring out the soap box. The part that really makes me angry is that the evisceration of this monument (which just went into effect a few days ago) was done essentially to allow coal mining on the land. This will likely result in the destruction of areas of the monument to mine ... coal. Yes, coal, the dying energy source that will be obsolete in a decade or two. A polluting fuel that you can burn for power when vastly superior nuclear energy and emerging solar power exist. Even if people insist on fearing nuclear power (which is silly in my opinion), other renewables (like solar), in my opinion, will make coal an obsolete energy source very soon. It makes me extremely angry to see land like this lose its protections so that some company can destroy it to extract a crappy, polluting fuel that will be unviable in a few decades while permanently destroying parts of this landscape.

There are arguments that this would enrich the local economy, but I am highly skeptical of that. I still do not believe that destroying even small parts of places like this is worth something as useless as coal. Nuclear plants have effectively made coal obsolete for decades (if they would be deployed in large enough numbers...), but even if they won't be built in large numbers, other options, like solar, will soon finish the job.

My main point with this last part is just that if you live in the US and ever have some sort of vote come up that involves protecting this monument, please vote accordingly (even though I doubt this will occur since this is an executive decision and I'm not sure Congress can do much here).

The good news is that the other half of the monument is still protected, for now.

I really hope that you have the opportunity to visit this place, and the rest Utah and the southwest, sometime. I really love the area and find it a fascinating place. I hope you enjoyed this post and learned something about the area!

Remember that this monument is, even with the land reductions, still enormous. I haven't seen 99% of it. Some of it, again, still hasn't been explored on foot. And, right under the surface, who knows how many new species of ancient extinct animals are hiding.

Let me know if you have any questions, comments, or if I got something wrong. Feel free to debate me on the monument reduction if you agree with the president's actions, by the way.

Thanks for reading!

All images not credited are my own. You are welcome to use them with credit.

White and red cliffs in southern Escalante monument

External Sources Used: (I have mostly referenced my own experiences and what I've read on signs and visitor centers near the area)

Pytochids from the Tropic Shale

Navajo Sandstone

Utahceratops Gettyi

Being A SteemStem Member

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Although I don't practice, my background is in the geosciences (BS in Geophysics with a minor in Geology). The American Southwest, as a whole, has some of the most interesting and complicated geology in the world.

Visiting the Grand Staircase is on my bucket list.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit