Higher Order Thinking: An Introduction

I define higher order thinking (HOT) as the production of highly coherent linguistic discourses (conversations and texts) about complex subjects.

Describing HOT is an interdisciplinary project, comprising elements of psychology and philosophy. My objective is to support learners and curriculum developers who believe that it’s important for people to develop deep thinking as a habit.

The project stands on two presumptions. Its main premise is the claim that learning about the processes which underlie thinking and learning helps people to think better and learn more.

That is, the process of learning to develop deeper and more coherent thinking is facilitated by understanding some basic principles of psychology and philosophy.

The second premise is that those principles, taken from academic texts and journals, can be translated into language which can be understood by inquiring learners who have never studied them. This essay is an attempt to demonstrate that.

Deep Thinking and Deep Learning: An Overview

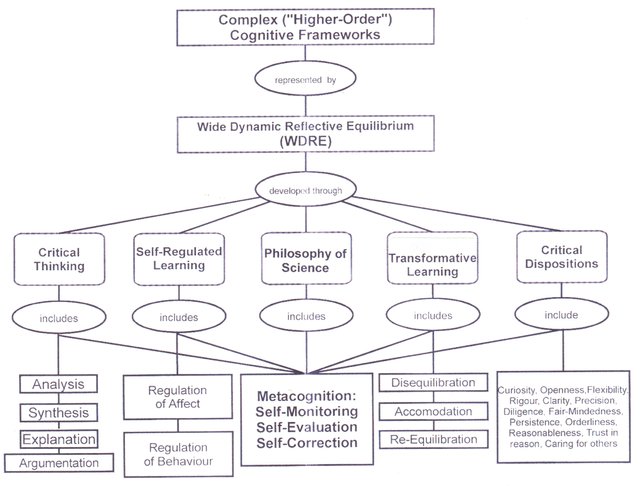

HOT comprises a set of theories about processes which are associated with deep thinking and deep learning. Those elements are described in the following sections.

Here’s a simplified two-dimensional overview of the global concept. The processes are specified in the rectangles at the bottom level of the diagram.

John Rawls [note 1] suggested that an ideal cognitive system would continually change and grow as it takes new ideas and new evidence into account. Wide dynamic reflective equilibrium represents an ideal set of beliefs and opinions that would continually account for the largest possible set of ideas that are consistent with all reliable evidence and all reasonable arguments. Unfortunately, perfect wisdom is unattainable, but some sets of ideas are better (more coherent, useful, beneficial, etc.) than others.

Metacognition

Metacognition is academic shorthand for metacognitive self-regulation, which means: correcting one’s own ideas (beliefs, opinions and theories). This practice is relevant to every aspect of deeply coherent thinking.

It refers to the processes of examining (and re-examining) the justifications for our beliefs and our opinions, evaluating their coherency, and correcting them whenever evidence or reasoning indicates errors.

It’s also called reflective (or reflexive) thinking.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking (CT) has been defined as “reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do.” [2]

Here’s a more detailed description, which was developed by a committee of forty-two educators (mostly philosophers and psychologists) who participated in a two-year study of CT:

“We understand critical thinking to be purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. CT is essential as a tool of inquiry.”

-Delphi Report, p. 3.

Despite the great number of professors who have claimed that CT is focussed on seeking the truth about things, that is a very popular misconception. CT is based on critical theory, which warns that thinkers and learners should never presume that our ideas or our arguments are absolutely true.

Here’s how the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes the postmodern revolution in philosophy which has superseded the previous paradigm (that is, truth-seeking):

“Postmodernist philosophers in general argue that truth is always contingent on historical and social context rather than being absolute and universal and that truth is always partial and ‘at issue’ rather than being complete and certain." [3]

CT is about appreciating the value of reasonable justification, that is, understanding not only what we should believe and do, but also why those things are better than other alternatives. According to contemporary philosophical standards, coherent reasoning, not truth, is the gold standard for human understanding.

CT includes developing and applying the following processes:

Analysis is the breaking down of discourses to examine their meanings; synthesis is its opposite: constructing explanations and arguments. Metacognition is essential to doing those things reasonably (that is, coherently).

Producing deeply coherent reasoning requires learning to apply these cognitive processes effectively from people who have had more practice in doing so.

The intent to apply CT is demonstrated by particular attitudes, or dispositions, which support effective inquiry. Some of the motives (critical dispositions) associated with that purpose are indicated in the above diagram.

Self-Regulated Learning

Immanuel Kant described three guidelines to developing practical wisdom. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy [4] has translated the following from his work Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View:

“…[N]ot even the slightest degree of wisdom can be poured into a man by others; rather he must bring it forth from himself. The precept for reaching it contains three leading maxims: (1) Think for oneself, (2) Think into the place of the other [person] (in communication with human beings), (3) Always think consistently with oneself.” SEP

In introducing this passage, Kant pointed out that perfect wisdom, the idea of a practical use of reason that conforms perfectly with natural law, “is no doubt too much to demand of human beings.” However, it is possible to manage ourselves in more or less effective ways with regard to achieving our learning objectives; that is, if we set any learning objectives, and if we’re intent enough on achieving them.

Self-regulation: The Psychology of Self-Management

When it comes to learning, educational psychologists have described a set of self-regulatory processes, each of which plays a part in managing ourselves to learn more effectively. [5]

Higher order cognitive development is an ongoing purpose; it doesn’t occur by accident. In addition to regulating our thinking (metacognition, described above), it also requires careful attention to managing our motives and our actions.

Managing our motives and our desires is called affective self-regulation or metamotivation. Metamotivation is about deciding which ideals are most valuable to oneself, and then applying them in action. Since this process includes deciding what’s important, it involves dealing with questions of morality and ethics.

A personal value is an idea (an abstract ideal) which someone believes is important, something that one want to experience, such as ‘wisdom’ or ‘justice.’

The processes by which metamotivation is applied in practice are: articulating one’s most important values and purposes (deciding one’s commitments); sharing these decisions with others (declaring them publicly); and engaging in ethical discourses with others to decide what we should or shouldn’t do to manifest our higher values in action.

I’ve described metamotivation in greater detail here.

According to this scheme, one of the most important processes involved in higher order cognitive development is engaging in discourses with others about what we should or shouldn’t do, and why. While making important decisions by ourselves is an option, social flourishing is produced by applying the values of communication, cooperation, and teamwork.

We can also regulate our behavior and our learning environments. For example, it helps to pay close attention when listening or reading, and to spend time thinking, talking and writing about what we’re learning. We can adjust the area around us in various ways, or move from one place to another, in order to focus on our work.

We can apply all of these practices to manage our learning.

Self-directed learning and learner-centred education are pedagogical theories which focus on what learners want to know and which educational methods are suited to their interests. These techniques are being implemented more and more widely (I suppose because they’re more effective than traditional teacher-centered methods). Here are some examples:

Centre for Teaching Excellence, University of Waterloo, Canada

Stephen D. Brookfield

A group at Concordia University, Portland, Oregon, USA

Hoboken Charter School, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA

Philosophy of Science

Science grew out of epistemology, the philosophy of knowledge and understanding. Epistemology was originally considered as truth-seeking, but in the postmodern world it’s seen as the study of justification:

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/epistemology

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/epistemology

“Because there is no clear dividing line between what can be accepted as truth, and what is conjecture, most scientists do not stray into this area. They slowly build upon accepted theories that only a major paradigm shift, or the refuting of a fundamental principle, can alter.”

Martyn Shuttleworth

In 1620, Francis Bacon wrote the seminal text on systematic empirical investigation, The New Organon (Novum Organum).

In it he invented objectivity.

Bacon proposed that we could manage to overcome the three barriers that prevent us from attaining true knowledge: human nature, “because the structure of human understanding is like a crooked mirror which causes distorted reflections (of things in the external world); fallacies, or errors of interpretation; and false presumptions, “the deepest fallacies of the human mind: For they do not deceive in particulars, as the others do, by clouding and snaring the judgment; but by a corrupt and ill-ordered predisposition of mind, which as it were perverts and infects all the anticipations of the intellect.” SEP

Since then, philosophers have become reconciled to idea that human perception and human language are inadequate to represent anything in the world with absolute exactitude. [6] While we may be supremely confident that many of our ideas about things are indeed the best interpretations that language can signify, we can at the same time understand that “truth is always partial and "at issue" rather than being complete and certain." [3]

“…[T]here can be no criterion of truth; that is, no criterion of correspondence: the question of whether a proposition is true is not in general decidable for the languages for which we may form the concept of truth. Thus the concept of truth plays mainly the role of a regulative idea…It does not give us a means of Finding truth, or of being sure that we have found it even if we have found it. So there is no criterion of truth, and we must not ask for a criterion of truth.” Popper

If we agree that an empirical inference is extremely well justified (in that all reliable and relevant evidence supports it), and that no thoughtful person would disagree, is it also important to insist that it must also be absolutely true? What beneficial purpose does that serve?

Believing that one’s beliefs are absolutely true may be a severe obstacle to learning. In 1997, Hofer and Pintrich published an extensive review of five independent educational research studies [7], which analysed the work of separate teams who investigated the correlations between university students’ ideas about knowing and their academic achievements. The reviewers found a consensus in the various studies’ findings. Each team reported that students who maintained that absolutism (absolute truth) was their standard for understanding performed worse academically than those who understood that the best knowledge is contextual, evaluative, constructed or reflective (rather than absolutely true).

It appears that people learn better if we realise that coherency, according to reasonable justification, is more important than truth.

Transformative Learning

Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget distinguished two types of learning, which differ in an important respect. [8] Assimilation is the process of learning something that’s consistent with what someone already understands. Accommodation occurs when we observe something that doesn’t fit with what we already believe, and we alter our previous beliefs in order to understand it.

According to Piaget, the new observation upsets the cognitive equilibrium of the observer; the resulting disequilibration is resolved by cognitive self-correction (re-equilibration).

You can read more about this at: britannica.com

Piaget worked with young children. Jack Mezirow (9) described a similar phenomenon, transformative learning, which may occur when adults face disorienting dilemmas. When evidence invalidates what one has long understood, confusion may produce a sense of inadequacy as one realizes that one’s meaning schemes have been less than completely coherent. This realization presents an opportunity for reflection and self-correction.

Transformative learning represents an alteration of one’s point of view. When a point of view changes, things appear differently; more meanings are revealed. Transforming a point of view isn’t a gradual process of learning to see things differently; it’s a discontinuous process wherein relative large changes occur in a moment.

Critical Dispositions

“In psychology, an attitude refers to a set of emotions, beliefs, and behaviors toward a particular object, person, thing, or event. … While attitudes are enduring, they can also change….Cognitive dissonance is a phenomenon in which a person experiences psychological distress due to conflicting thoughts or beliefs. In order to reduce this tension, people may change their attitudes to reflect their other beliefs or actual behaviors.” Kendra Cherry

Educational psychologists have described a set of critical dispositions, attitudes and tendencies which appear to be relevant to learning deeply and maintaining coherency. According to Facione and his panel of educators:

”The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and the circumstances of inquiry permit.”

-Delphi Report, p. 3.

Of course (as Kant remarked about perfect wisdom), it’s impossible to maintain all of these attitudes perfectly, but if one intends to engage in CT, it’s possible to cultivate them.

Ennis added a social (moral) dimension to the list of critical dispositions; he acknowledged the importance of caring for the interests of other people. [2]

It seems clear that an open-minded, inquiring, diligent and rigorous attitude is important to developing HOT. As we work on developing greater discernment, we can also work on developing our dispositions in order to produce greater satisfaction and social success.

Applying Higher Order Thinking

It’s impossible to predict the limits of what an inquiring self-directed and self-regulated learner might discover. If deep learning (accommodation) is more important to us than maintaining what we already understand, then we’ll be open to new ideas and new ways of thinking. If it’s more important to maintain our historical points of view, then that’s what we’ll do.

People are motivated by our values and our desires.

Values and purposes relate to each other in hierarchies. Some ideals contribute to more general (or higher) purposes; these are called instrumental values.

For example, the value of ‘nutrition’ is instrumental to ‘wellbeing.’ ‘Caring’ is instrumental to ‘morality.’

All beneficent values are instrumental to social flourishing. If social flourishing is important to us, then we can apply moral values to guide our thinking and our actions.

Aristotle described the ideal human lifestyle (eudaimonia, or social flourishing), defined as “an activity of the soul in conformity with excellence or virtue.” [10] In practice, flourishing requires careful consideration of our actions and their consequences. The idea ‘arête’ (moral excellence, or virtue) refers to rational consideration of human actions, with the purpose of deciding what we ought to do (or not do). This, as Ennis suggested, represents the ethical aspect of critical and higher order thinking.

It’s been widely advertised that lifelong learning, the commitment to inquiring into unfamiliar ideas and circumstances, is instrumental to achieving success throughout one’s life.

“Your ability to expand your mind and strive for lifelong learning is critical to your success.”

Brian Tracy

“The more you learn, the more sides you’ll see of the same issue. Reading, watching intelligent television and holding conversations with others will educate you about other points of view. It may or may not change your mind, but it’ll help you to understand that there is more than one side to every issue.”

Whitney Coy

“In order to truly empathize with others, increase social awareness and build relationships, we must intentionally seek out ideas that differ from our own. This is critical not only to the health of individual relationships, but also the health of society.” Caroline Vander Ark & Mary Ryerse

There is no canonical curriculum for practical wisdom. Postmodern thinking and critical theory have begun to filter through the academy, but many educational systems are still rooted in the historical regime of received and authoritative truth. While philosophers and the more iconoclastic self-directed learners learn to inquire critically, most teachers, professors and students remain dedicated to the paradigm of absolutism, the idea that only one set of beliefs (the true ones) is to be maintained, and anything that conflicts with one’s knowledge is to be refuted or ignored. This approach leaves little room for criticality, accommodation or novel insights.

Because critical theorists are in the minority among education professionals (and among parents), most people haven’t learned that truth-seeking is not the best approach to education.

I close with my message to those who are working to reform higher education:

Critical coherency could be promoted by implementing curricula for higher order thinking in preservice teaching programs, and in the graduate programs of every university faculty. If student teachers and graduate students would spend their university years learning to apply the processes associated with HOT, then they would be able to demonstrate and explain them for the benefit of future generations of students.

References

[1] Rawls, J. (1999). Collected Papers of John Rawls, S. Freeman (Ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[2] Ennis, R. H. (1987). A taxonomy of CT skills and dispositions. In Baron, J., Sternberg, R. (Eds.), Teaching thinking skills: Theory and practice (pp. 9-26). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman, p. 10.

[3] Aylesworth, Gary, (2015). "Postmodernism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/postmodernism/

[4] Williams, Garrath, (2017). "Kant's Account of Reason", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-reason/#MaxComHumUnd

[5] Pintrich, P. R., & Zusho, A. (2002). The development of academic self-regulation: The role of cognitive and motivational factors. In A. Wigfield, J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation, (pp. 249-284). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

[6] Popper, K. (1979).Objective Knowledge: An evolutionary Approach. Oxford University Press.

[7] Hofer, B. K., & Pintrich, P. R. (1997). The development of epistemological theories: Beliefs about knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Review of Educational Research 67, 88-140.

[8] Piaget, J. (1971). Biology and knowledge: an essay on the relations between organic regulations and cognitive processes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[9] Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[10] Aristotle (1962/2000). Nichomachean Ethics. Translated by Martin Ostwald (New York, NY: MacMillan/Library of the Liberal Arts, 1962). In F. E. Baird & W. Kaufmann (Eds.), Ancient philosophy (pp. 364-434). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. (1098a, 16-17)

Why people became so dumb today and incapable of critical thinking is because the way the system was designed intentionally, once they graduated they became an asset to the rich people, that's one of the essence of capitalism, it benefits those who have money to run their own business, but the negative effect to that is people doing repetitive task will lose their creativity that can be a danger to real economy without creativity and talent we cannot progress to where we are today.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

"*Why people became so dumb today and incapable of critical thinking is because the way the system was designed *"

Agreed. What can we do that might resolve this?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Regarding critical theory and thinking, what we often do in my classes is go into the Allegory of the Cave, do activities like "Two Truths, One Lie", examining things from different angles but also questioning motivations.

For example, in my poetry class, I went off of a list of poems that are commonly assigned to college freshmen, and then after doing the typical analysis, I would open up discussion to have them question why these poems are assigned to college freshmen, if there's possibly an agenda, if there's subtext, or if it's simply to go with what's familiar, theme and such. It takes a little while for them to accept that yes, it's okay to question those things, but once they do they really get into it.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Can't you preserve absolute truth alongside a coherence theory? In other words, the realization that human understanding is often partial (which is obvious to most people) need not militate against absolute truth, right?

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

A really well referenced and easy to read piece of work (which is not easy to pull off!).

Kudos! (and I have resteemed it for the benefit of others!)

Cheers,

@Shenobie

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you very much, @shenobie. I'm very glad to hear this.

Mike

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @rortian!

Your post was mentioned in the Steemit Hit Parade for newcomers in the following categories:

I also upvoted your post to increase its reward

If you like my work to promote newcomers and give them more visibility on Steemit, feel free to vote for my witness! You can do it here or use SteemConnect

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Thank you, #arcange.

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @rortian! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPDownvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit