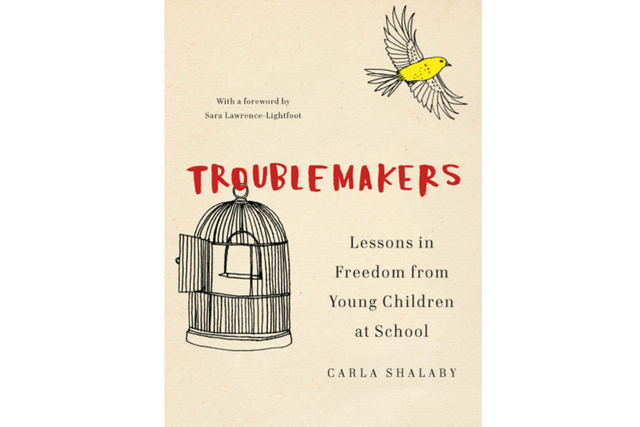

This is a wonderful book that will make you pause four times to wipe away tears and reflect on the pathological need for obedience and conformity that has become the hallmark of contemporary school systems in the United States and here in the UK. All royalties go to the Educational for Liberation Network, a US-based coalition that views education as the practice of freedom.

Author Carla Shalaby writes loving and sensitive profiles of four children that she describes as "canaries" - people who are the first to fail in a dangerous environment and who therefore serve as a warning to others of a developing catastrophe. The term, which she applies to the school system, comes from the deep mining industry but it is also one that has been used in the design sector for many years, where the mantra of looking for causes of failure and then evolving the design to address them is what drives improvement. Sadly, schools have been very slow to adopt the philosophy, often concluding that the problem driving poor behaviour lies within the child and not the system itself.

By the time you have finished reading the book, you may be wondering whether these children are canaries or lions. One thing is for sure: each of the children who form the focus of this book poses profound problems to their school management systems. All four end up on medication, yet in each case it seems plausible that changing the system rather than putting them on prescription might have been more humane. Even if medication was the appropriate response - and Carla appears torn on the issue - she wants us to consider that these four children were acting as alarms in a system that is bad for all of us. Rather than dealing with the issue, she suggests that the school system prefers just to mute the alarm, with long term effects on adult social, economic and political structures.

First up is Zora, a beautiful African/Puerto-Rican/American girl who finds herself in a school that is overwhelmingly white and described as outputting "white-bread Americana" by her hard-working, deeply committed and experienced Reception teacher. Zora is one of those children who stands out without being outstanding, in the school's vernacular.

At home, her self-confident parents teach her to be proud of her culture and identity. They celebrate her creativity and teach her that she has as much right to be loved as any other person. Her bedroom features a quote from Karl Marx (that great friend of white America): "Philosophers have sought to understand the world. The point, however, was to change it." And so she goes to school, her hair set in exquisite braids, full of energy, sure of her right to be loved and treated fairly, and quickly discovers that her school has been designed for a different type of person.

Zora is naturally sociable and a great communicator. Troubled by the cultural disparity between home and school (being happy to blend in versus being happy to stand out), she fronts it out, using humour to attract the other children's attention and then being reprimanded by the teacher for getting the whole table laughing. Thus, she has to live in a paradox - she thinks she deserves attention but, when she gets it, she is told off for being naughty. At home she is encouraged to think of herself as a change-maker; at school she is told not to challenge any of the conventions that keep the system working. As the other children learn that they are not supposed to laugh without permission, this six year old girl finds herself having to adopt ever more disruptive strategies to secure attention.

As her sadness at being isolated turns to defiant insistence, her hard-working and deeply invested teachers also find themselves living within a paradox. They argue that Zora needs to learn how to take her place in a conformist, white culture business world, but they also worry that they are suppressing her ability to show a white world how it might benefit if it embraced cultural diversity. They see that the other children are learning that female black children don't fit into the system very well, and that Zora is learning that she just isn't up to the task.

Trapped in a system designed for a different type of person, Zora is encouraged to secure praise by suppressing her need for social connection, much as children at boarding school are taught that suppressing their emotions is the best way to secure approval. It is equivalent to taking someone in pain and, rather than treating the cause, threatening them with more pain if they don't suffer in silence.

Eventually, her inability to fit in (or is it principled refusal to give up on her core needs?) leads the school to invite her mother to a meeting with her teachers and a psychologist. Alone in an office, she listens to their analysis: that Zora's exuberance, creativity and sense of drama are causing her to become isolated and fall behind in maths; that she could make so much more progress if only she could control her impulses. Reluctantly, she agrees to their suggestion that Zora be given medication for ADHD. It feels like the family have been asked to medicate their culture.

Thus, aged seven, Zora finds herself living in a world where mundane tasks remain mundane, but the happy rebellions of the past are no more. Her mother has trusted the school in agreeing to medicate her daughter; the daughter has trusted the mother in taking the medication; and in one of the saddest passages in the book, the author imagines a future in which Zora finds a place in white society but loses all that made her so much like her wonderful, assertive, fun and successful parents.

The question of whether Zora would have been diagnosed with ADHD if she had attended a multi-racial school hangs heavy in the air. Zora's attempts to be what the author describes as "hyper-visible" are met by an equally strong desire to make her invisible - to eliminate behaviour that might cause her to stand out. At another school, perhaps one with a black head and many black teachers, she might have blended in right from the start and been celebrated for her dramatic flair and sense of fun.

This principle is explored in relation to two other children, both of whom attend a multi-racial, multi-income, highly inclusive school with staff that represent many races, genders and sexualities. It is a school where teachers are known by their first names and there are highly visible messages promoting tolerance, emotional sensitivity and even encouraging protest against unfair systems and practices.

One of them is Sean, a red-headed Irish-American boy whose mother combines single-parenthood with a career in marketing. On a home visit, the author notices that Sean is able to sit quietly next to his mother watching a documentary about the making of wasabi. However, he struggles at school. His teacher, Emily, is highly committed to the idea of students as independent learners but it has to happen in a room designed for traditional 'chalk and talk' lessons. As such, the space often feels cramped and Sean is unable to get the attention he takes for granted at home.

Despite being busy, Sean's mother is happy to take time to explain things, to negotiate and let the timetable slip a bit to accommodate the here and now. These, she thinks, are good life skills - but at school they cause huge amounts of disruption. Maths lessons overrun, sports lessons finish early and all the children are eventually banned from sharing food because the teacher doesn’t want to apply the ban just to Sean.

It emerges that the emphasis on independence clashes fundamentally with Sean's need for close emotional contact. The school has not noticed how the loss of his father has left a huge gulf in his life, and when he demands attention the staff respond by sending him to the naughty step. He starts to fall behind academically because he is rarely in the classroom when exercises are being explained, and does not have time to complete the task before the lesson ends.

As Sean becomes more upset, he starts fighting with his friends. His mother then has him assessed for ADHD and he is medicated. He becomes more focused but starts to cry and the author is torn between two possibilities: that the medicine is enabling him to release pent up emotion, or that it has left him drowning in a pool of sadness that he used to avoid by deliberately and consciously distracting himself.

We never find the answer to the question and as a reviewer I am not in any way qualified to do more than report the author’s perspective. However, while he is clearly a very troubled child who may well be suffering from ADHD, it seems equally obvious that an education delivered at home by his mother would be significantly less troubling for him than one delivered by strangers in a crowded room.

These two examples highlight the common theme of the book - that all four "trouble-makers" are in fact very young people struggling to articulate entirely valid needs in a setting that is unable to meet them. Whether the school is teaching uniformity or individuality, the response is to ask the children to suppress their needs, and (especially with traditional schools) to ask families to live according to conventions that align with the needs of the school.

It's hard, in this context, to see how a natural-born actress, warrior, hands-on learner or artist is going to get the support that he or she needs, until school has decided the time is right. Carla argues that a child whose natural inclination is to see the whole community move forward together must live in a world where individual achievement is emphasised; children who are unique and proud of it must learn to suppress their identity; others who look at an adult and see an equal rather than a boss must learn to subordinate themselves; children who like choice must get over it; and those who look to elders for guidance and support must get on with it on their own.

When they protest, it is not because they are uncaring - it is because they do care, and are desperate.

Carla finishes by highlighting a very troubling situation in Detroit - a city almost abandoned by the state, in which the schools are full of dangerous mould, with mice running freely through the classrooms. Faced with conditions that are educationally useless as well as physically dangerous, the teachers (who were banned from striking) all called in sick on the same day. Their managers subsequently asked whether it might be possible to strip them of their teaching qualifications.

This response - to punish the attempt to draw attention to a problem - is what Carla considers to be the natural long term consequence of being raised in a system that does exactly the same thing. She asks us, instead, to look at the person raising the objection and ask what might be motivating them to do so. We might, for once, stop complaining about "attention seekers" and consider what is better - someone who points out problems, or someone who has given up and withdrawn.

Equally, we might consider the concept of childism, as defined by Dr Chester Pierce and introduced to me by Sophie Christophy. It is "the basic form of oppression in our society… for it teaches everyone how to be an oppressor and makes them focus on the exercise of raw power rather than on volitional humaneness." Should we isolate children who recognise this and protest, or (as Carla suggests) re-make schools as places where such approaches would be put in the same category as slavery?

Troublemakers is indeed a deeply troubling book. As Carla says, "It seems impossible to blame a caged bird for its own death in a toxic mine, but we nonetheless manage to do so." It seems fitting to finish by quoting a poem in defence of those who dare to speak up in an environment that demands their acquiescence:

His wings are clipped and

His feet are tied

So he opens his throat to sing.

And his tune is heard

On the distant hill

For the caged bird

Sings of freedom.

Carla Shalaby, "Troublemakers: Lessons in Freedom from Young Children at School" is published by New Press (2017) 240pp., ISBN: 978-1620972366

Congratulations @seanmcd! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit

Congratulations @seanmcd! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit