On March 11, at the 2018 South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Austin, Texas, Elon Musk announced his intention to send SpaceX’s first “interplanetary ship” to Mars in the first half of 2019.

Musk is known for his aggressive — a kind way to say “wildly optimistic” — timelines, which are themselves a function of his giddiness as an innovator. As a result, observers combine a distrust of the initial timeliness with a full faith in Musk’s ability to carry out the project in due course.

Musk has, after all, launched industry-disruptive powerhouses such as PayPal, Tesla, SolarCity, SpaceX, and the Boring Company. Founding any one of these companies would, by itself, represent a historic accomplishment. Place them all within a single Curriculum Vitae and people will start to listen.

Significantly, what Musk has to say isn’t limited to such mundane details as quarterly vehicle production forecasts (though he admits they stress him out). Instead, he muses on large topics, such the danger that artificial intelligence poses for humanity, the possibility that we’re living in a simulation, and the inevitability of World War III.

Or, like at SXSW, he’ll discuss how human beings might get to Mars.

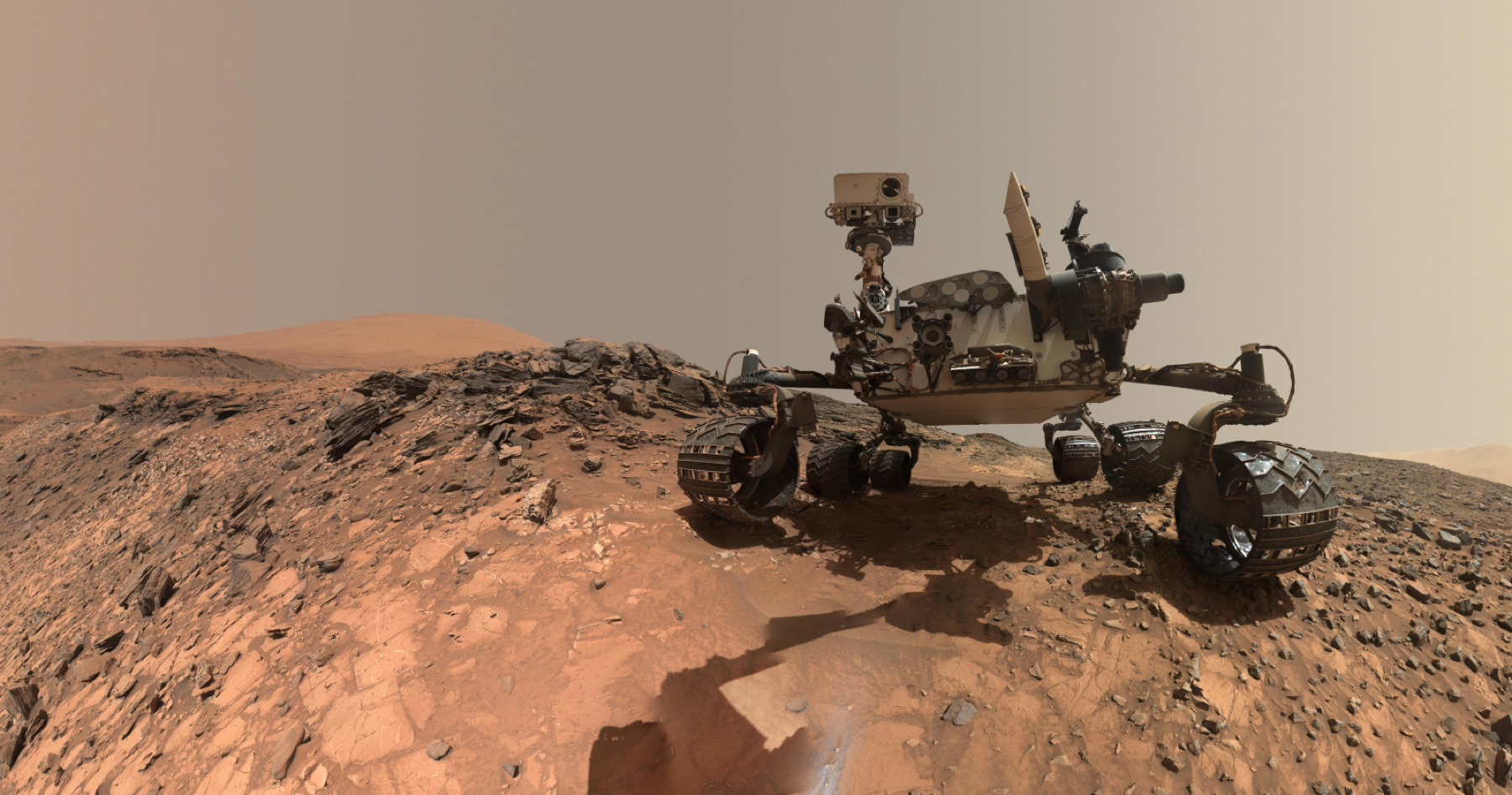

Most of the press surrounding this concept has predictably focused on logistics. Ten years ago we weren’t sure we could reliably get humans to the Red Planet. But if Musk is right, we’re within just a cosmic blink of an eye from that happening — even if his prediction is slightly off.

But the science of getting there is one thing; what life might look like there—indeed, how society might function there—is another. Musk has discussed both topics.

Life On Mars

Musk envisions a human colony of a million people on Mars, preceded, of course, by an intrepid set of early, capable, and fearless pioneers.

"For the early people that go to Mars, it will be far more dangerous. It kind of reads like Shackleton’s ad for Antarctic explorers: Difficult, dangerous, good chance you’ll die. Excitement for those who survive."

What’s certain is that the first colonizers of the Red Planet aren’t likely to raise our collective blood pressure about the intricacies of intergalactic governance. There will be more immediate concerns; considerations of survival, not civilizational durability, will occupy the minds of these early pioneers to Mars.

Even by Elon Musk’s standard of cheap ($200K a head), it will still be incredibly expensive to send people there, let alone sustain them once they arrive. And it won’t be a tourism trip — those going will have to build all the infrastructure necessary to ongoing survival.

While the first wave of travelers will be focused on securing the most basic conditions for sustenance — air, water, food, shelter — the next wave will utilize expertise and ingenuity to enhance those conditions. These engineers, scientists, doctors, and technologists will attempt to go from making sure Mars is survivable to making sure it’s livable, a subtle though real distinction.

But as the colonial population increases, the colony will presumably start to resemble our planet’s major cities. While colonizers won’t expect the types of amenities of a New York or a Tokyo, they will begin to expect more services than an Antarctic outpost. Soon, mandatory personnel will give way to — in likely succession — wealthy tourists, entrepreneurs, economic migrants, opportunists, and…criminals.

If that’s a particularly bleak perspective on a possible future sequence of events, keep in mind that this assessment assumes the colonization is supported by SpaceX — an American company led by a chief executive who believes personal agency and freedom of action are among civilization’s greatest achievements.

Of course, there’s no reason to believe Musk’s vision is inevitable.

Other Space Racers

Even Musk himself suggests that companies other than SpaceX should be competing to colonize this new planet. But why does Musk envision a corporate competition on Mars? Space flight, until recently, has been the exclusive purview of nation-states — entities large enough to be able to devote the massive resources necessary to equip such missions.

SpaceX may be led by a motivated and capable leader, but it is empowered by dozens of institutions and individual investors that the company has courted over the last 12 years. This type of funding requires dedicated teams to acquire resources, strict timelines for performance, and achievable exit strategies.

But SpaceX and its rivals wouldn’t be the only game in town.

For the most part, nation-states are comparatively unencumbered by fundraising and performance benchmarks. Administrations of democratic societies can hardly expect to devote, say, 25 percent of their tax revenue to space exploration. NASA’s entire 2017 budget (Mars exploration aside), for example, was $19.3B, or 0.5 percent of the U.S. federal budget.

China’s space program budget is roughly $3B, or less than 0.1 percent of the national budget, according to some observers. Nevertheless, China benefits from a convenient ambiguity between private industry and state-owned enterprises that skews their true investment numbers. In contrast to Western nations, China is comfortable outsourcing innovation to its private sector and rewarding a budding domestic company with the ample power of national tax revenue.

Of course, the U.S. and China aren’t the only participants in space. Russia, the E.U., and, most recently, India, are all players on the intergalactic stage.

Russia may struggle to be a long term contender. It’s not due to a lack of expertise — they were, after all, the first society to launch us into space. Yet the space program is a government enterprise, and will likely remain so unless and until the system of government changes. Russia’s budget is disproportionately dependent on oil and gas. Yet these revenue streams are compromised by the emergence of new oil and gas sources, as well as the global move away from fossil fuels. Thus, Russia’s ability to be competitive in space over the long haul depends largely on the ability of its government to diversify its revenue sources.

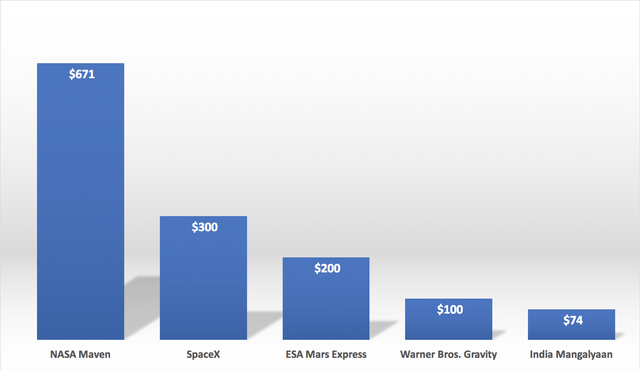

The European Space Agency (ESA) is, on paper, the most capable entity to compete with NASA and SpaceX. It is a partnership of 22 E.U. member states, responsible for significant contributions to the International Space Station, the Mars Express orbiter, and most recently, Rosetta, the ambitious and partially successful attempt to land a rover on the Comet 67 P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, over 300 million miles away from Earth. The ESA could achieve remarkable breakthroughs not just scientifically but bureaucratically.

Meanwhile, as the U.S., Russia, China, and the E.U. were all laboring to send payloads into space, India successfully launched a Mars orbiter for just $74 million.

According to Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister:

"A one-km auto rickshaw ride in Ahmedabad takes Rs 10 per km and India reached Mars at Rs 7 per km, which is really amazing."

It is also a testament to the capacity of a nation-state to achieve an objective consonant with, and fully reliant upon, all its available resources. India’s Mars mission cost less than what it cost Warner Brothers to produce the 2013 space film Gravity, which was released in the same year.

Assuming SpaceX, the United States, China, the E.U., Russia, and India are all potential players, there could also be a few other corporations in the mix. SpaceX may be the first pioneer, but other landing outfits will likely follow.

The Biggest Questions Surrounding Interplanetary Colonization

Will they coordinate the logistics of this human colony back on Earth? Will they cluster around the same zones and pool their resources and talents? Will they focus on staking out territory akin to 19th century European colonists? Will they vie for technological, military, and economic dominance? Which model of colonization will each entity promote?

If you ask Musk:

"Most likely the form of government on Mars would be a direct democracy, not representative. So it would be people voting directly on issues. And I think that’s probably better, because the potential for corruption is substantially diminished in a direct versus a representative democracy."

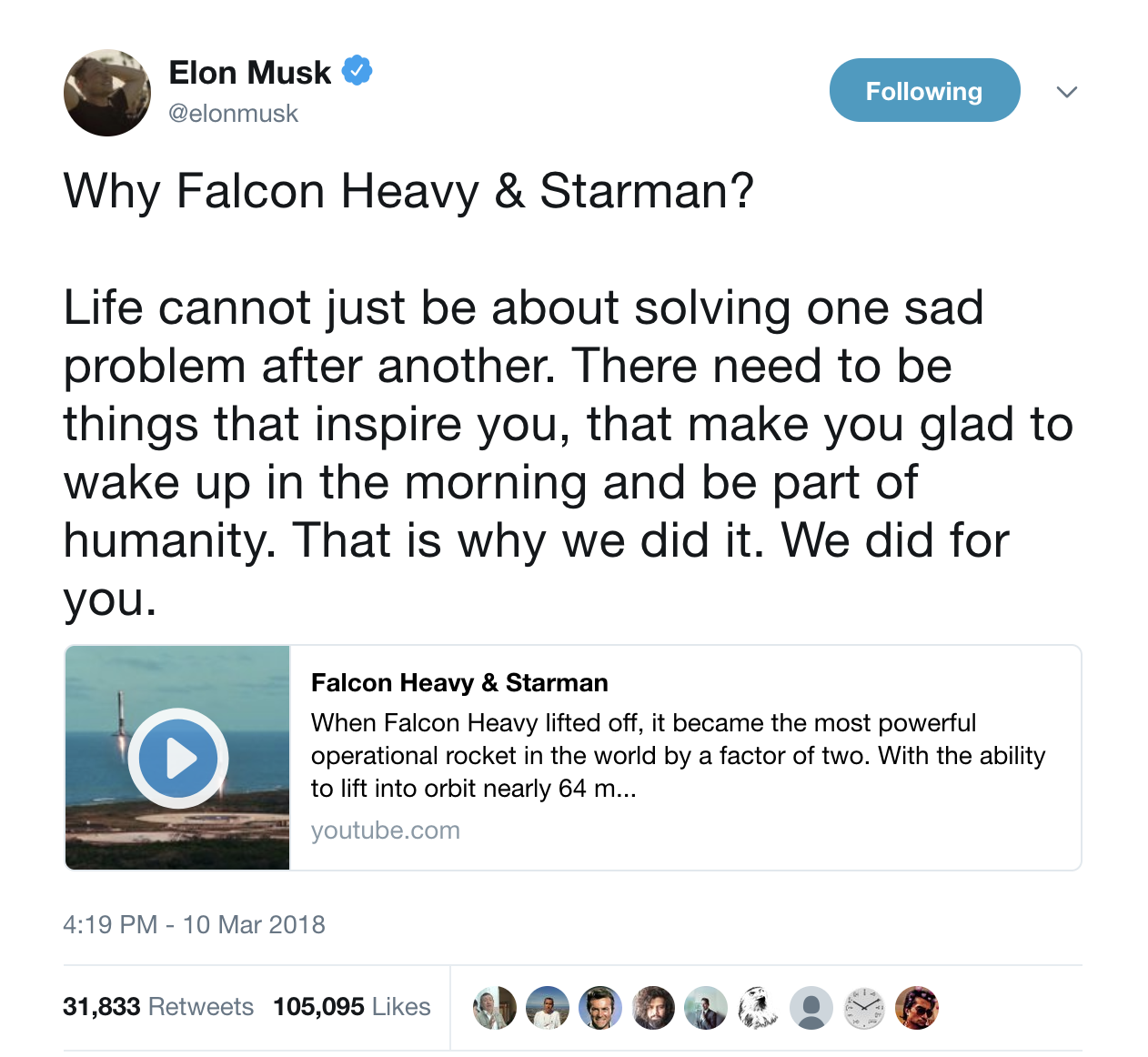

But how much thought has he really given this issue of governance in space? He certainly implies he’s thought about it a lot. While we terrestrially-minded humans are warring over the existentially meaningless definition of our individual and group identities, or “one sad problem after another,” Musk seems preoccupied with what he characterizes as the inspirational goals of greater humanity.

Musk has been vocal about the dangers of artificial intelligence — an amorphous technology the average person knows about mostly through science fiction — though it was just weeks ago that he discovered his companies had profiles on Facebook. Visionaries tend to have interesting blind spots.

Perhaps he really is more concerned with the science of it all. Perhaps he’s more preoccupied with missions whose launch dates are nearer than whatever the real launch date for a Mars mission happens to be. Perhaps he is prioritizing what he would like to see rather than what is the likeliest governance scenario.

Not to get too bogged down in psychoanalyzing Silicon Valley CEOs, but perhaps all of this stems from an aspirational source: Musk senses the zeitgeist — and the toxicity of our politics — and believes his purpose is uniting us in one of our most fundamental desires: to explore our universe.

Part of Musk’s popularity is a result of the care he takes in not being drawn into the politics that now reliably reach into every corner of our lives. But is it overly optimistic to believe we won’t export these problems to a new colony millions of miles away?

A good case can be made that the societal framework(s) we set up on Mars will not ultimately be invulnerable to the vicissitudes of Earthly life. Our Martian colonies will likely resemble the tendencies, dispositions, and norms — written and unwritten — found on our own planet. And it will be the events chronologically closest to the Mars mission that will have the greatest impact on the shape of things on the Red Planet.

Let’s consider a possible future, a set of developments that could come to pass as Mars is being colonized.

In 2038, the United States’ federal budget is almost entirely consumed by three mandatory spending programs: healthcare, retirement benefits, and interest on the debt. Any “discretionary” spending, such as the military, infrastructure, education, science, energy, or space requires issuing new debt. This roils confidence in economies underpinned by dollar-denominated transactions. Investors flee to safer havens, potentially including China’s RMB, cryptocurrencies, or commodities. Knock-on effects compound as international markets restructure to account for increased volatility.

In many categories, China exceeds the United States as a global superpower. It has successfully created a middle class for whom basic prosperity is a given and whose focus is naturally oriented toward greater self-determination. Chinese tourists travel the world by the hundreds of millions and are exposed to societies unencumbered by the same censorship and political repression they experience at home. The yawning gap results in domestic political pressure that the Community Party of China works to channel into defensive ends, like nationalism. Domestic anti-establishment efforts, escaping repression at home, manifest common supranational ideologies.

Surveillance is total and virtually unlimited. Privacy is a quaint notion embraced by a small and marginalized group of recluses, modern Luddites, and populations without access to the latest technology. For non-democratic societies, complete transparency is enforced by government decree in the name of security and social cohesion. For democratic societies, business drives surveillance in the interest of actionable market data, while consumers drive it in the name of security. Digital identities are mandatory, required for travel, commerce, and socialization.

Science, medicine, and technology are transcendent, though access to their benefits is unequal. The wealthiest of the world are genetically engineering their children and embedding tech into their persons, while the poorest are still struggling to get access to clean water, roads, and healthcare. Developing economies and remote, undefended territories attract major powers hungry to support increasing energy demands and to ensure the primacy of their own forms of government.

Whole industries, such as freight and transportation, are beginning to be replaced by automation that renders the less technical incapable of reentering the workforce, further exacerbating problems of social cohesion and economic fundamentals.

Conflicts are both national and transnational, continuous, ambiguous and asymmetrical, rarely involving direct military stand-offs, and leave unaligned groups incapable of amassing defensive measures.

Is such a scenario too grim?

Musk has expressed concern about the likelihood of WWIII and the dangers of artificial intelligence. Both of those observations could be considered a distillation of the potential pitfalls mentioned above. Few things are more likely to torpedo humanity’s attempt to settle a distant planet like a world war or a hostile takeover by artificial intelligence. The last space race was catalyzed by the race for global military dominance. Will the effort to colonize Mars be a modern replay of that process?

Technology has always been disruptive. But the interconnectedness of modern societies and the proliferation of new tech poses a far greater threat to today’s world than the new technologies of the past had on their respective times. The pace of evolution gave former societies dozens, if not hundreds, of years to adapt to the types of change we experience in a matter of years today.

Responsible modern technologists have a duty to consider the impact of their work, whether or not it is ethical, and all the ways in which it may affect our collective future. Mark Zuckerberg’s ongoing struggle to manage the power of his product is a perfect example.

When the stakes are large enough, little meaningful engineering occurs without consideration of potential failure modes. Unlike commerce, however, failures of governance are regressive, all-encompassing, and often lethal, setting back progress on all fronts of society by years or decades. In the proper framework, competition breeds excellence — but it can also breed violence and oppression.

To suggest a direct democracy will “most likely” be the system of governance of a future human colony is highly optimistic. What we will need is expert, meticulous planning, not sci-fi musing. Musk is one of the likeliest candidates to propel the human race into Mars, yet this does not mean he is the right person to map out our future there. The organizational and structural aspects of colonizing Mars—as opposed to its scientific and engineering challenges—require serious reflection, not armchair theorizing.

Those Who Ignore The History of Colonization Are Doomed To Repeat It

History is replete with lessons on the pitfalls of colonization. The very word connotes an understanding of the past for which modern civilization has struggled to come to agreement. That’s because a defining component of earthly patterns of settlement was the diversity of societies responsible for it: nation-states, races, ethnic groups, migrants, refugees, etc.

All of these were, nevertheless, human. Mars represents an opportunity to grow together as a species. We can arrive, even as separate entities, under a modest framework that accounts for our diverse perspectives and priorities. History informs us of potential alternatives: arms races, open conflict, genocide.

It doesn’t have to go that way with interplanetary colonization. But to avoid it, we must encourage — today — meaningful, open, and honest debate about the values and principles that can help humanity survive the heat and pressure necessary to reach the species’ true escape velocity.

Congratulations @tweakofficial! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Do not miss the last post from @steemitboard:

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!

Downvoting a post can decrease pending rewards and make it less visible. Common reasons:

Submit